The Irascibles: The Birth of American Abstract Expressionism

This photograph of New York-based Abstract Expressionist painters was published in Life magazine in January of 1951. The photograph, dubbed “The...

Tom Anderson 13 February 2025

20 July 2023 min Read

When we think of a meander we usually think of a winding riverbed of the Meander River in Asia Minor or an ancient decoration of broken lines that is repeated in an uninterrupted sequence. But, for one man meander wasn’t a geographical term nor decoration, ornament, or aesthetics. It had a completely different meaning. In this article, you will find out about an artist who has devoted his entire life to this one motif. His name is Julije Knifer, a Croatian painter, who lived and worked in Croatia, Germany, and France and exhibited in many cities around the world.

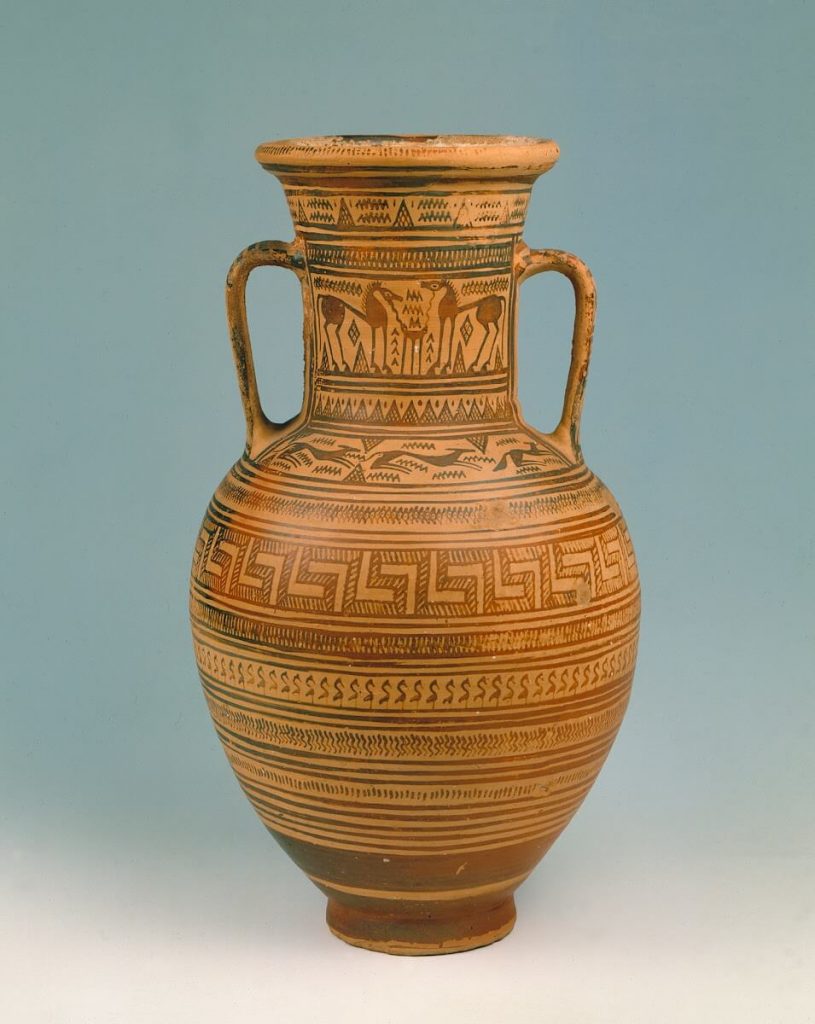

Meander: monotonous, unoriginal, meaningless through its endless repetition and yet used in various cultures as a decorative motif. Beginning with the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods and continuing in many early civilizations, including Mayan, Etruscan, Egyptian, Byzantine, and ancient Chinese, as well as in Greek and Roman art, meander was a common decorative element. It has been applied in architecture, and on various items such as pottery and clothing. Greek vases, mainly during the geometric period, were perhaps the main reason for the broad use of meanders. Today meander is often replicated in fashion, jewelry, interior design, and architecture.

Julije Knifer was born in 1924 in Osijek, Croatia. In 1956 he graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, Croatia. By the beginning of the 1960s, he had reached an uncompromising decision that resulted in painting meanders for the rest of his life. He had reached the end: the meander which cannot be simplified further. At that time he was still living in Zagreb and was a member of the Gorgona Group, the new avant-garde movement. Alienated from the mainstream system and barely known in its own surroundings, it later achieved historical reevaluation and international affirmation. In the 1970s, he began collaborating with German galleries, where he had the opportunity to produce large-format paintings. In 1991, he moved to France, to the small town of Sète on the Cote d ‘Azur. In 1994, Knifer moved to Paris, where he remained until his death in 2004. The process of work itself was very important to Knifer’s mental, physical, and spiritual engagement. Also, music was an essential component of his works: the music of Russian composer Igor Stravinski, whose rhythm he wished to apply in his paintings, was essential in his art.

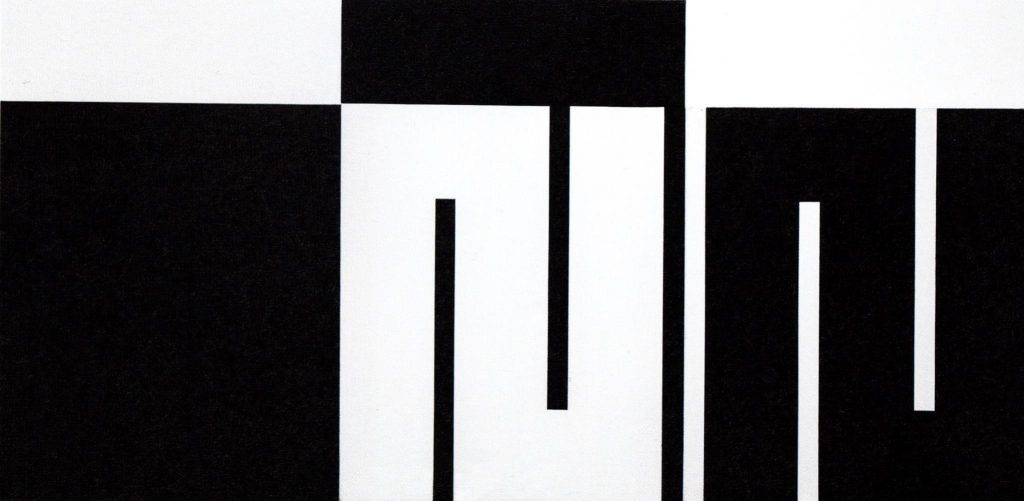

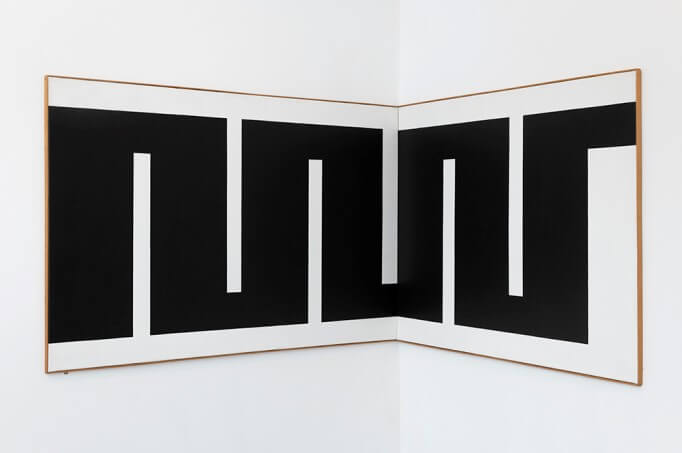

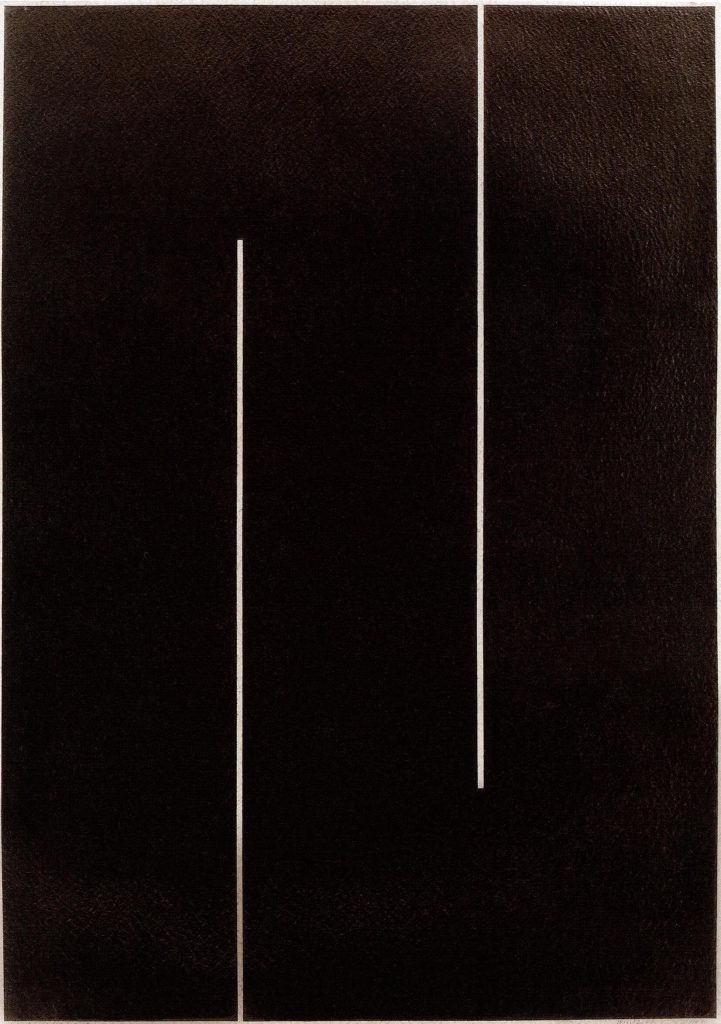

Julije Knifer defined his paintings as a “series of facts that constitute a meander or a series of meanders, which are in the end just one meander.” A black and white painting he called anti-painting. White on a black background or black on a white background, horizontal or vertical, on one panel, two panels, uninterrupted.

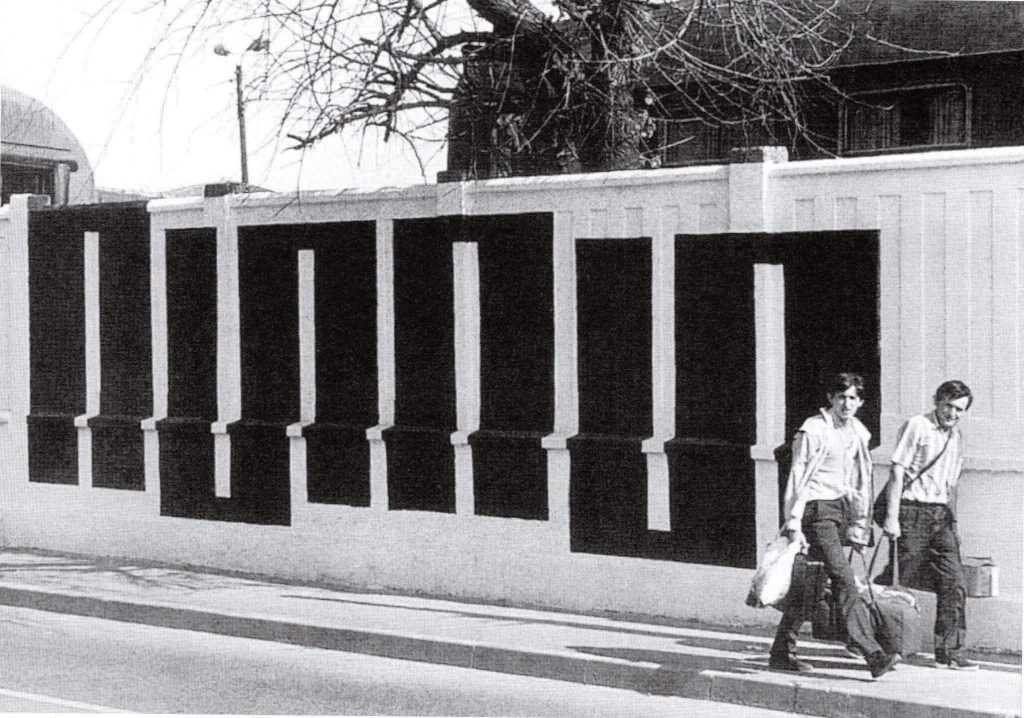

Meander in the corner, meander as drawing on A4 paper, as b/w collage, meander on canvas, and even as a mural in public space, left to erosion under the influence of the weather or because of painting over.

In his pencil drawings, he tried to banish light from the surface and reach absolute darkness.

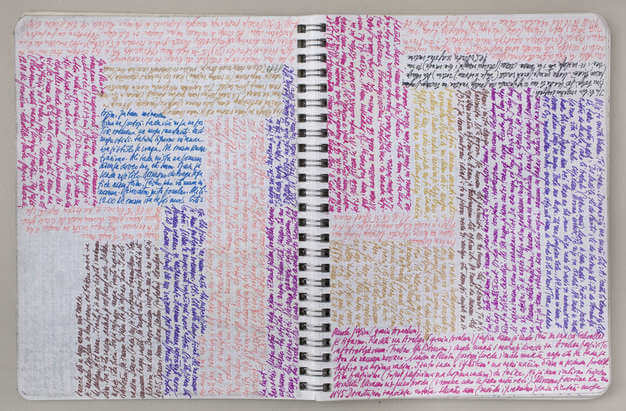

It is not possible to talk about just one of Knifer’s paintings because the meander is continued. There are thousands of minimally different variants of meander in which the flow of direction is entirely irrelevant. Monotonous repeating of equal or similar elements creates a specific rhythm that had also determined him as a person. “An escalation of uniformity and monotony,” as defined by Knifer himself. He had chosen to equalize the practice of painting with the course of his life. In the 1950s, he started to write Banal Diaries, a collection of observations from his daily life. In this way, he repeated the monotony of his meanders in his texts.

Although to the shape of meander symbolic meanings were always ascribed, most commonly it symbolized infinity and the eternal flow of all things, Knifer explicitly renounces any symbolical and allegorical extension. In his work meanders are not at all essential content.

What was it he was doing? Was it a classical form of constructivism, colorist constructivism or kinetic constructivism? As the author himself said, labeling is unnecessary. It is what it is: a painting without identity that, through endless repetition, strives towards absurdity.

Radmila I. Jamković (ed.) (2014), Julije Knifer: Uncompromising – a retrospective. Exhibition Catalogue. Zagreb, Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb, from 20. 09. 2014. to 06. 12. 2014.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!