5 American Impressionists You Need to Know

Impressionism is an art movement that originated in France in the 19th century. Artists associated with this movement are known for their dream-like...

Ruxi Rusu 4 December 2024

This season’s crop of museum exhibitions around New York City includes the highly-anticipated retrospective of Linda Goode Bryant’s experimental art space for Black artists that was founded in the mid-1970s. The Just Above Midtown art gallery made its imprint on the New York art scene decades ago as a laboratory for artists to experiment. Under the direction of Goode Bryant, this historical overview of JAM at MoMA celebrates the explosion of creativity and resourcefulness of the community that gave life to this legendary art gallery.

New York City was a hotbed of experimental activity throughout the 1970s, a multi-faceted era of activism and collaboration. Some art stories from this period, mostly known to the participants and acknowledged through the diligence of others, remain tucked away in the footnotes and archives of art history. Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces at MoMA digs into the extensive archives of Linda Goode Bryant, the director of Just Above Midtown (JAM) art gallery from 1974 to 1986, for an insightful exploration of the eventful journey of this art gallery and its director.

Referencing its first location at 50 West 57th Street in midtown Manhattan, near MoMA and other blue-chip galleries, JAM was established as a commercial art gallery for the promotion of Black artists. Soon after it opened, the gallery became a nonprofit art space and eventually was forced to relocate downtown first to Tribeca and then to its final location in Soho. Over the course of its run, JAM oversaw more than 150 exhibitions, 130 performances, and created opportunities for well over 600 artists. This created a legacy that has impacted a broad network of artists, art professionals, and collectors.

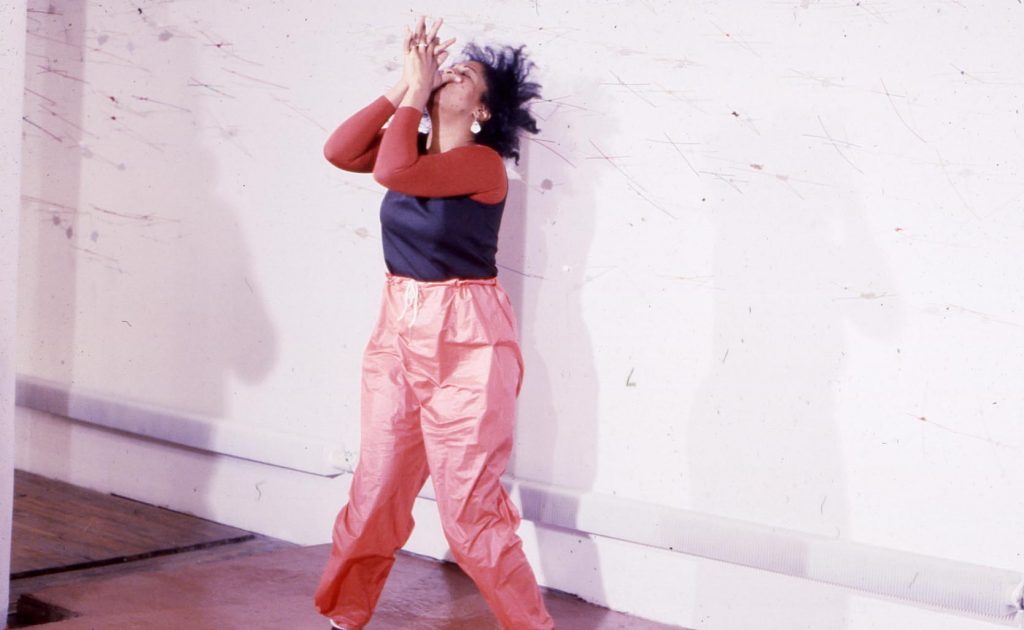

Senga Nengudi performing Air Propo at JAM, 1981. Courtesy Senga Nengudi and Lévy Gorvy.

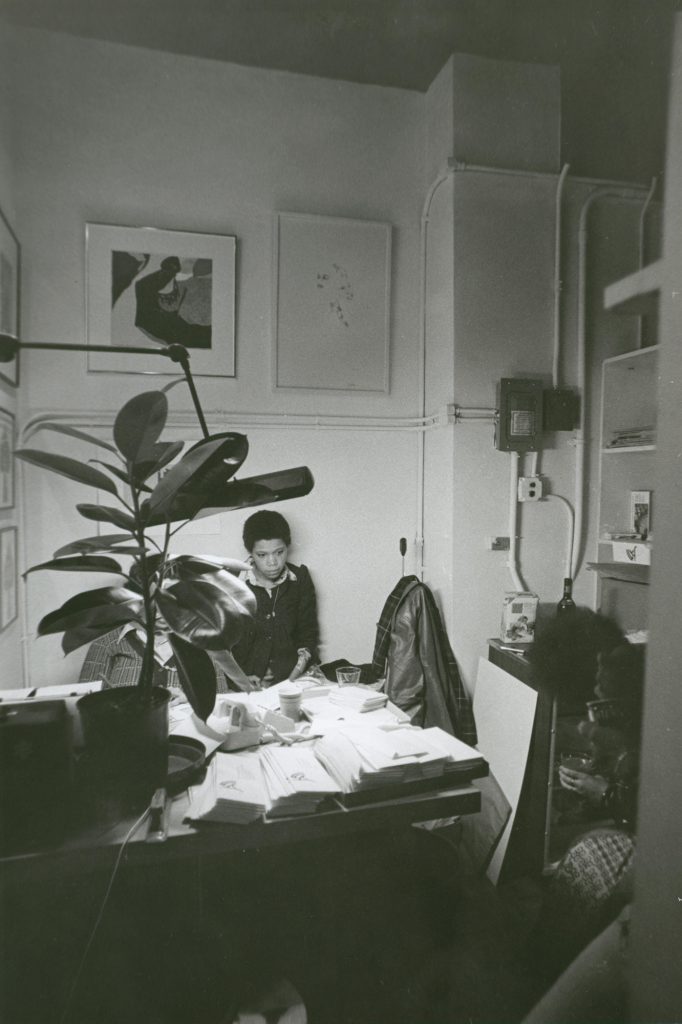

Prior to opening JAM, Goode Bryant was an education fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a position that she left early to join the education department at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Attuned to the needs and desires of Black artist communities, Goode Bryant envisioned a space that would allow these artists the freedom to experiment and collaborate within a supportive infrastructure offering the practical resources to develop professional careers as artists. JAM was conceived as an autonomous space, not in reaction to the exclusion of Black artists from mainstream art galleries but as a place of creativity and collaboration that did not replicate the methods of the traditional art gallery system. Goode Bryant’s groundbreaking vision embraced new technologies, Black conceptual art, and a proactive approach to the education of artists and collectors.

As a young single mother of two small children, Goode Bryant relied on a supportive community of artists, art professionals, and bourgeoning collectors to assist with the daily operations and ambitious programs of the gallery throughout the years. The need for childcare was acknowledged through a Saturday mom’s group that evolved into the open-minded curriculum of the Sunshine Circle Preschool in West Harlem that appealed to a small group of like-minded parents. For a brief period, the gallery offered homemade lunches for a small fee that were paired with a lecture from a curator, historian, critic, or collector as a way to get more people into the space, one that also attracted successful individuals from the worlds of film, television, music, fashion, and finance.

Linda Goode Bryant and Janet Olivia Henry (obscured) at Just Above Midtown, 57th Street, December 1974. Photograph by Camille Billops. Courtesy of the Hatch-Billops Collection, New York.

Throughout its entire run, JAM was on the brink of financial collapse, operating under the burden of mounting credit card debt, unpaid bills, predatory collection agencies, and the constant threat of eviction. Goode Bryant and those involved with JAM were undeterred by this precarious situation and persevered despite the lack of wealthy donors or large governmental grants. Credit card debt, volunteer labor, and inventive entrepreneurship created the means for JAM to support its mission to be a space for experimentation.

Goode Bryant’s community-based grassroots approach to getting it done was based on her childhood experiences of living in self-supporting and self-contained Black communities; places denied basic services by the state. This notion of self-reliance fueled JAM’s cultivation of Black collectors whose purchases not only benefited the artists and the gallery by creating a market for this work but gave these individuals the opportunity and confidence to expand their interests as private art collectors.

Linda Goode Bryant photographed by Dwight Carter, c. 1974. Courtesy of MoMA.

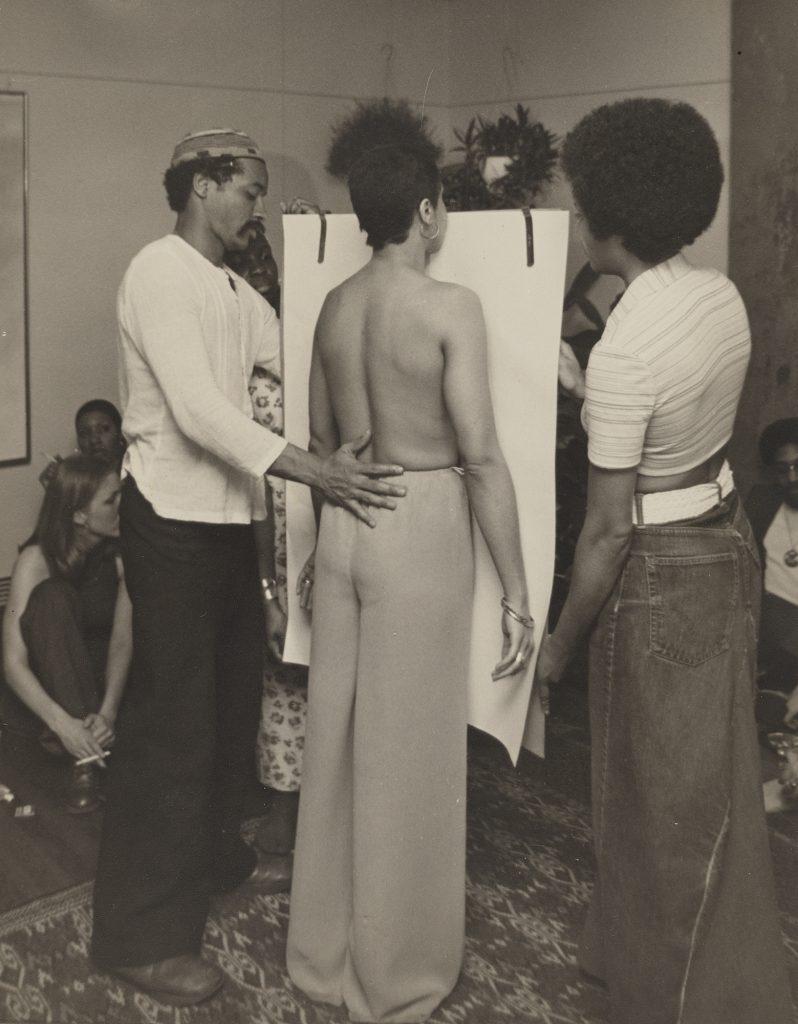

Cross-disciplinary collaboration among Black artists was paramount for the JAM community, one that included a staggering number of established and legendary players in the art world today. Of the numerous artists to have shown or performed at JAM, David Hammons made his solo debut in New York with the Greasy Bags and Barbecue Bones exhibition in 1975. The run of this show included a Body Print-In fund-raising event that invited participants to make body prints under the guidance of Hammons. Senga Nengudi took over the small midtown space in 1977 for her solo exhibition R.S.V.P. featuring her signature sculptures of nylon stockings filled with sand and stretched across the space from wall to wall and from floor to ceiling.

Several months later, Howardena Pindell, who at that time was also a curator at MoMA, showed a collection of recent paintings constructed from the tiny circles extracted from manilla folders through the use of hole punchers, a form that has occupied this artist throughout her career. In 1980, Lorraine O’Grady made her first public appearance as her alter ego Mlle Bourgeoise Noire at a JAM exhibition opening wearing her iconic dress and cape made from 180 pairs of white gloves. O’Grady activated this fictional character with a performance that gently admonished some of her fellow artists for being too cautious.

David Hammons (left) and Suzette Wright (center) at the Body Print-In held in conjunction with Hammons’s exhibition Greasy Bags and Barbeque Bones, Philip Yenawine’s home, 1975. Photograph by Jeff Morgan. Courtesy David Hammons. Collection Linda Goode Bryant, New York.

In addition to the aforementioned artists, Camille Billops, Lowery Stokes Sims, Fred Wilson, Randy Williams and countless other individuals known across the art world and establishments today were key participants of the JAM community, one that was not exclusive to Black artists and professionals.

The 1976 exhibition Statements Known and Statements New presented the work of JAM artists Hammons, Noah Jeminson, Jorge Luis Rodriguez, and Raymond Saunders alongside their white counterparts, Jim Dine, Helen Frankenthaler, Jasper Johns, Robert Motherwell, and Robert Rauschenberg. Despite ongoing financial uncertainties, JAM’s mission was further crystallized after it joined the downtown alternative and experimental art scene of the early 1980s, remaining open to the inclusion of and collaboration with artists and professionals of various backgrounds. Goode Bryant encouraged her artists to use the spacious layouts of the downtown spaces as creative laboratories for expansive thought, performances, and experimentation with new media such as film, video, animation, and sound.

Good Bryant is a visionary and after the gallery closed in 1986, she worked in city government, pursued her interests as a filmmaker, entrepreneur, activist, and more recently founded ProjectEATS, a network of small-plot farms and related programs in low-income NYC neighborhoods.

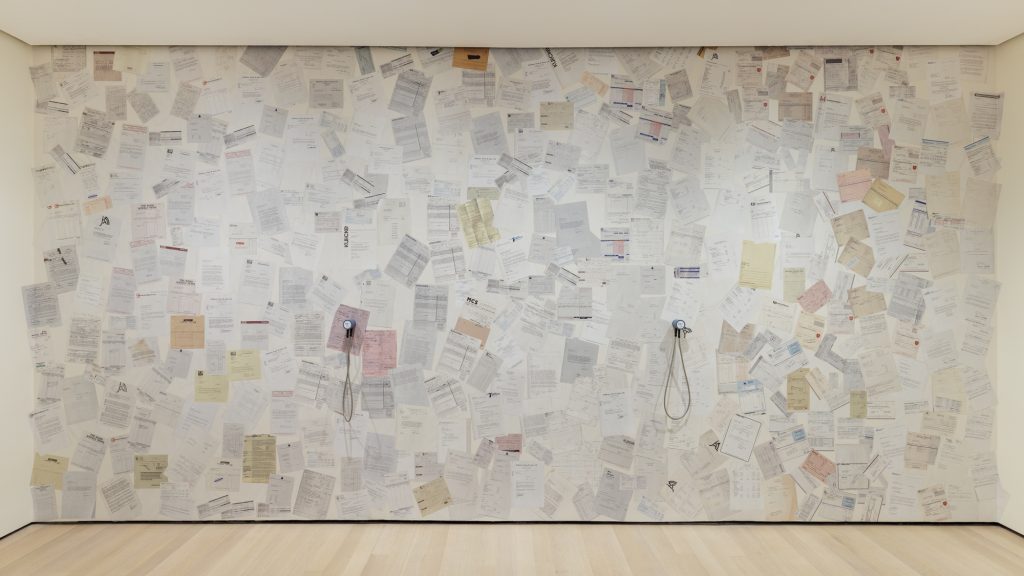

Installation view of Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA. Photo by Emile Askey.

The retrospective, as overseen by Goode Bryant, addresses the disparities between her midtown art gallery and this museum. The financial obstacles encountered while running JAM that ultimately led to its demise in comparison to the multigenerational wealth that has sustained the institution hosting this retrospective are succinctly summarized in a wall text that reinforces the socioeconomic chasm between the two spaces as well as underscoring the uneven distribution of obstacles and opportunities.

The meticulous archives maintained by Goode Bryant after JAM was evicted from its third and final space formed the basis of the exhibition and catalog that includes a detailed reconstruction of the gallery’s impressive timeline. Two large galleries feature a selection of original works, videos, and documentation of performances that were presented by JAM. The exhibition is an educational overview of the gallery’s activities; primarily of what was shown, what took place in the spaces of JAM, and what happened behind the scenes.

Installation view of Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA. Photo by Emile Askey.

The business of running an art gallery is the subject of a corridor featuring an entire wall covered in reproductions of unpaid bills, letters from collection agencies, eviction notices, and other administrative records. It is a candid look at running a gallery with limited resources.

On the opposite wall is a monitor playing outtakes from a video made as part of JAM’s educational incentive The Business of Being an Artist. While artistic exploration is the focus of the two main galleries, this corridor anchors these moments of art history to the practical limitations that although they led to the closure of JAM did not stand in the way of Goode Bryant and her community of artists’ ability to think big.

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces at MoMA encapsulates the synergy of experimentation, growth, and determination that was fostered during the JAM years with Goode Bryant at its helm. This exhibition ensures that this gallery and its legacy are remembered as one of New York’s most compelling art stories.

The show at the Museum of Modern Art was realized in partnership with the Studio Museum in Harlem and runs through February 18, 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!