5 Ultracontemporary Artists Redefining the Korean Art Landscape

The dynamic South Korean art scene is quickly becoming one of the most prominent globally, blending rich traditions with cutting-edge innovation. And...

Carlotta Mazzoli 13 January 2025

7 August 2022 min Read

The 17th century world map from an Ottoman book on the discovery of the Americas Tarih-i Hind-i Garbi (History of the West Indies) points to Mecca and the Kaaba as the center of the world. Indeed, the centrality of Mecca for Islam is undeniable as according to tradition it is believed to be the first place where man worshipped one God alone, and it was where Abraham and Ismael rebuilt the house of worship, the Kaaba, which had begun there by the first man – Adam. See how Hamra Abbas, a contemporary artist interprets the Kaaba in her works.

Since then, the Kaaba has remained the holiest and the most iconic feature of Mecca, and its high status has been confirmed and grounded by the Quran which established it as the quibla, the direction of daily prayers, and the destination of the Hajj, the obligatory pilgrimage and one of the five pillars of Islam.

In Mecca, spirituality goes hand in hand with commerce, granting the souvenirs purchased during the Hajj a particular significance: once at home, they will take a place of honor and will be counted among the most precious objects ever bought. It was these objects that stirred Hamra Abbas, to create her Kaaba artworks.

Hamra Abbas (b.1976) was born in Kuwait into a Pakistani family, educated in Berlin and Lahore, and now living between Pakistan and the United States. She admits that she owes the diversity of her artistic practice to her “quasi-nomadic life, where nothing is definitive” and she tries to keep her persona indefinite, too: although Islam is one of the dominating themes in her art, it’s not clear whether she is a believer or not.

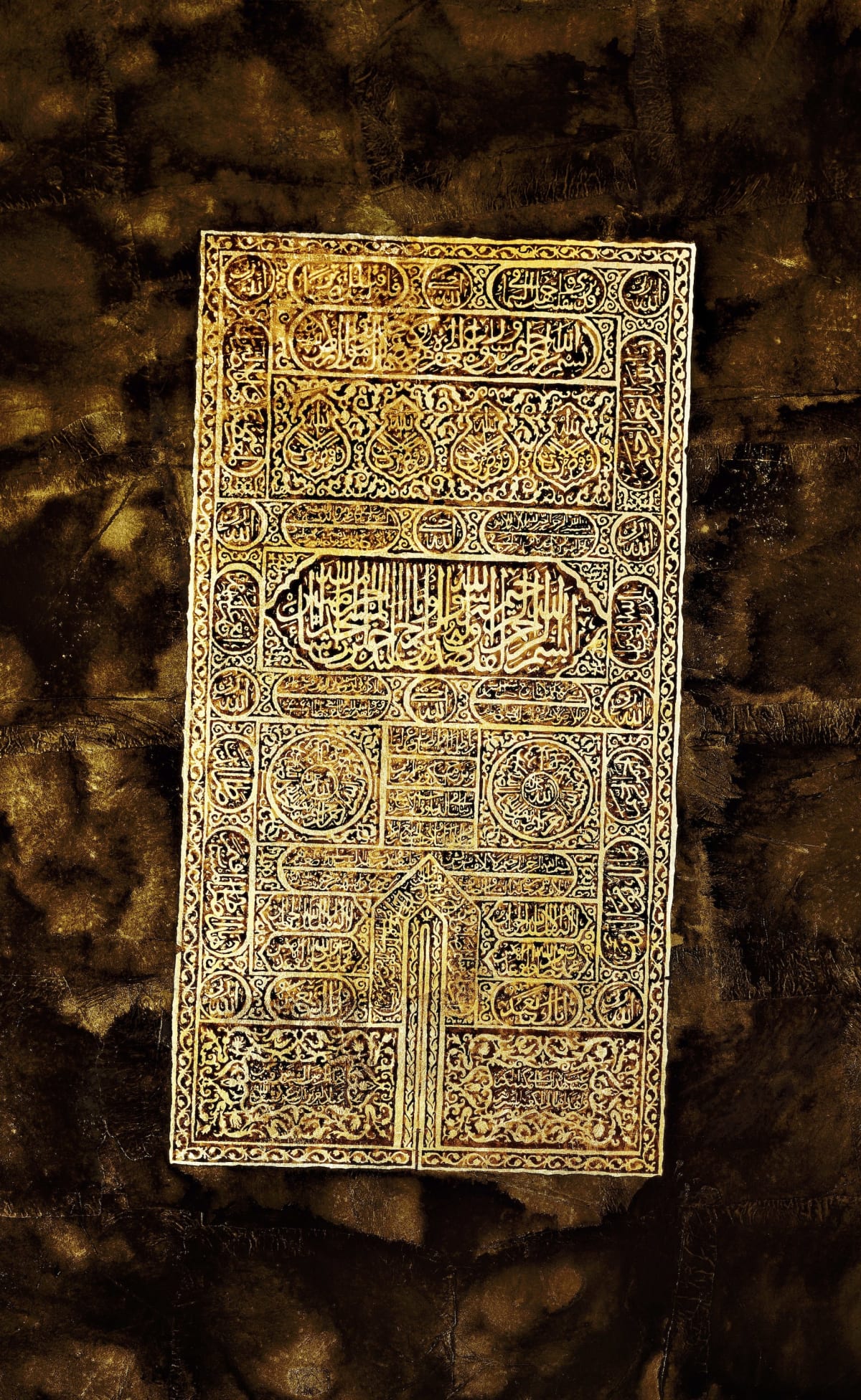

A print Wall Hanging I was installed on the façade of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston as part of Abbas’ 2011 residency. It was a depiction of a dusty plaster cast facsimile that Abbas had found hanging askew in her mother’s house. As she recalled, “it sparked an inquiry about objects of religious significance in a neglected, sad state” which led her to explore the relationships people form with souvenirs that are meant to represent something “greater”, and to question whether sacred objects retain their spiritual resonance even if they are divorced from their surroundings and are subjected to multiple reinterpretations.

In order to illustrate the question of authenticity and translation of meaning between the original object and its facsimile, Abbas mimicked the translation process with her artistic technique. First, she made a painting of the plaster cast of the gold-embroidered textile – the kiswa. Formally trained in the Indo-Persian tradition of book miniature painting, Abbas chose to paint with gouache on Wasli paper, which is a type of handmade paper used specifically for miniature painting. Yet, she departed from tradition with her next step, as she photographed the painted image to eventually transform the digital picture into a print. The scale of the work, as well as the merging of the traditional practices with the contemporary media decontextualized the Kaaba and presented it purely as an object, divorced from its spiritual aura.

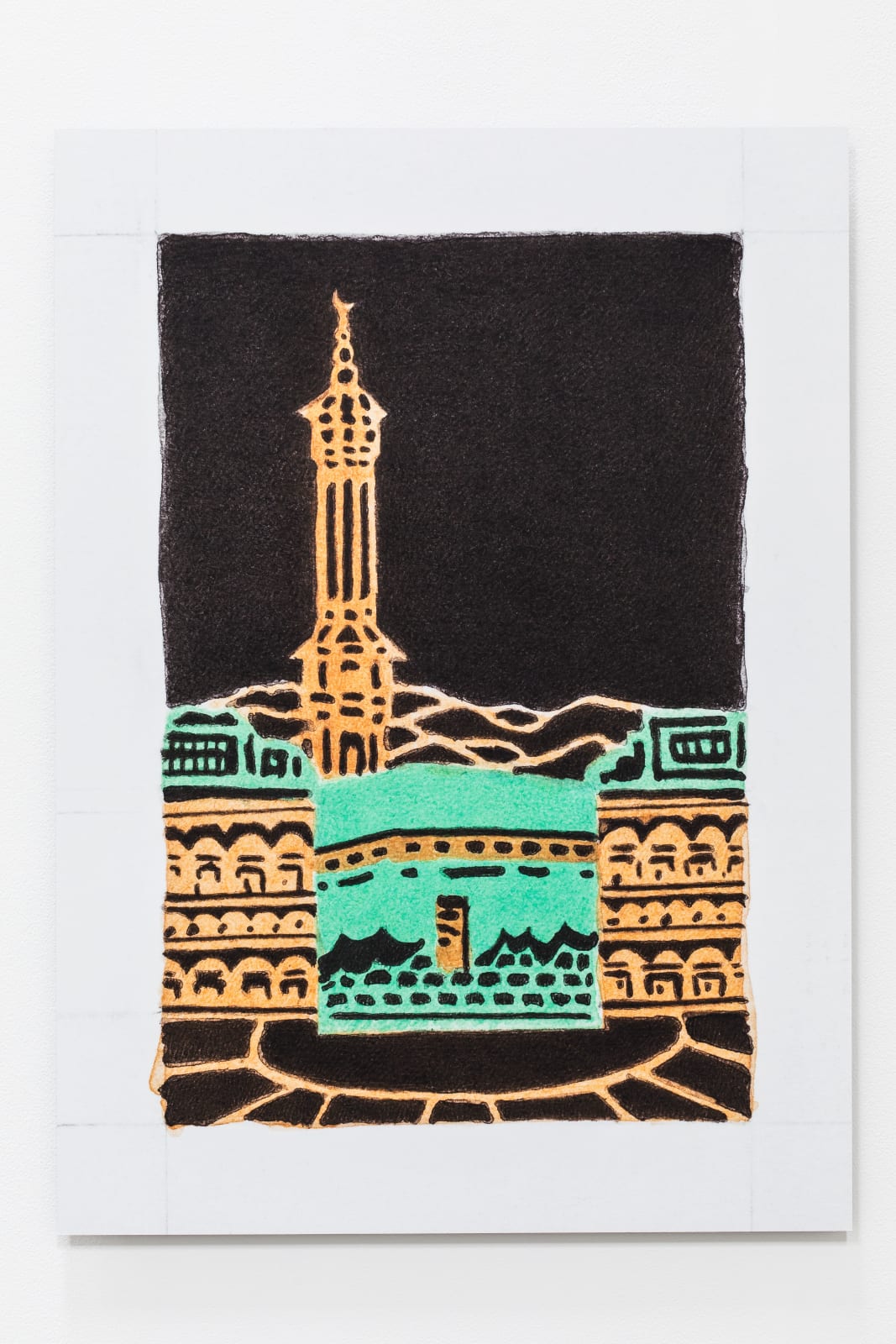

On this occasion Abbas left behind devotional objects and turned towards a larger concept of the construction of sanctity of items and buildings, basing her examination on the example the Kaaba as the ultimate place of worship. Also this time Abbas abandoned painting for another medium as she picked digital print, yet nevertheless, she made a hint at tradition because she printed her images on the Wasli paper she had produced herself.

To draw attention to the essence of the Kaaba’s cubical form, Abbas broke it down into two unadorned rectangles, one placed atop of the other. Despite this reduction to the basic minimum, the final shape was still immediately recognizable as the Kaaba. This way Abbas revealed how meaning determines form: the seemingly abstract rectangles gained a spiritual significance by their particular arrangement in space. “If we look at the square without mystical faith, as if it were a real earthy fact, then what is it?”, Varvara Stepanova wrote in 1909 referring to Malevich’s Black Square. Still, the same question could easily be asked in 2019 about Abbas’s rectangles.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!