5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

4 December 2024 min Read

Wassily Kandinsky – a lawyer turned painter, a painter turned lecturer, a green-fingered man for whom a house with a garden was a curse (as he would spend hours digging and sowing instead of working). Rightfully considered one of the fathers of abstract painting, he made a breakthrough in art history by introducing his theories on color and line in his practice.

Interestingly, however, he did not keep a consistent style throughout his career and, as the years passed, Kandinsky’s inspiration changed and so did his painting.

Kandinsky decided to quit his job as a lawyer and teacher for a couple of reasons. One of them was an exhibition of Impressionists in Moscow that he went to see in 1896. He was particularly shocked by Claude Monet‘s studies of haystacks which to him, thanks to Monet’s subjective perception of color, represented something else. He would write:

That it was a haystack the catalogue informed me. I could not recognize it. This non-recognition was painful to me. I considered that the painter had no right to paint indistinctly. I dully felt that the object of the painting was missing. And I noticed with surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me, but impressed itself ineradicably on my memory. Painting took on a fairy-tale power and splendor.

Kandinsky’s painting of beach baskets in Holland is his own approach to the study of seasonal changes in light and color. We can see the brush strokes which are long and brisk. There are also definitely influences of Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh.

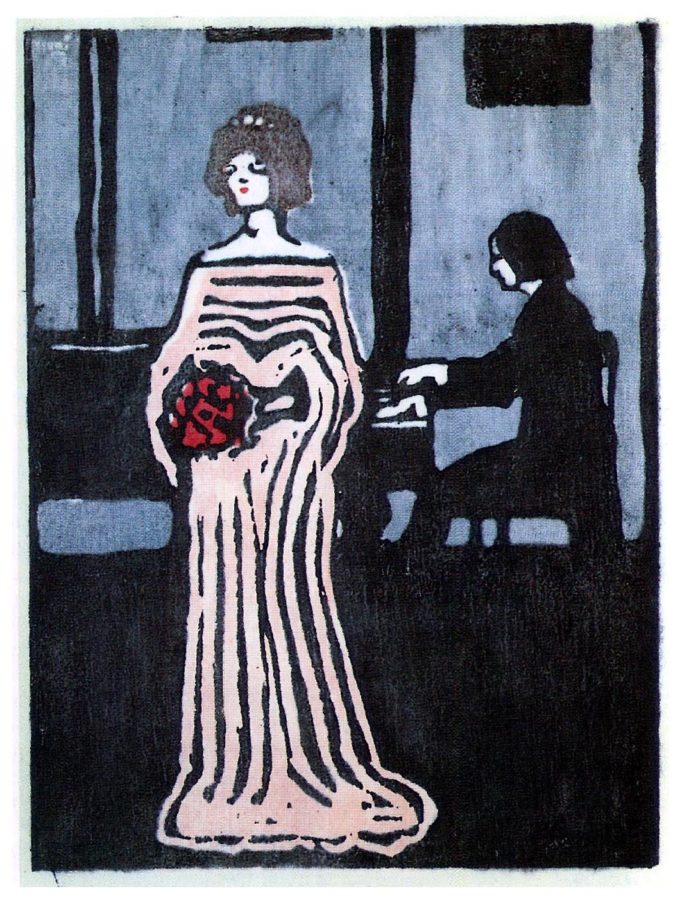

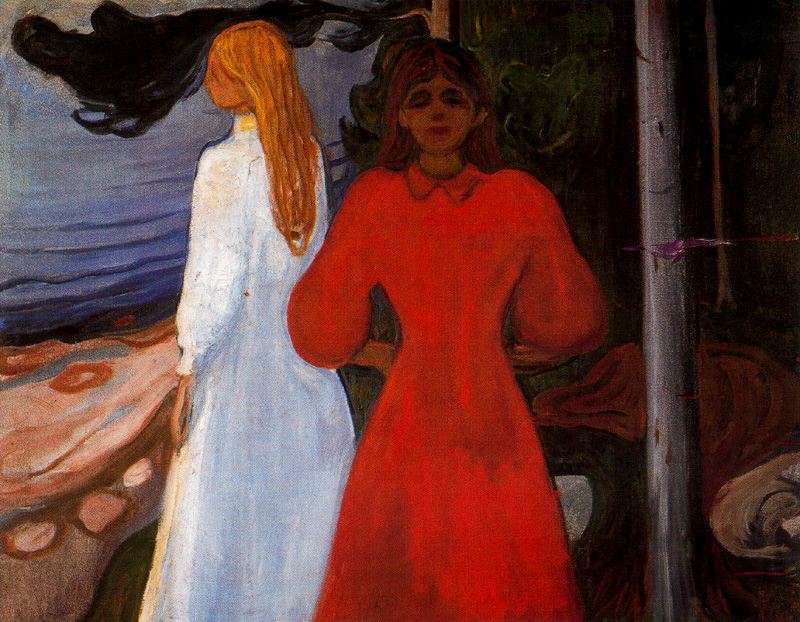

It might be a long shot, but in this painting, I see a strong influence of Edvard Munch. I don’t mean the fact that Munch also used lithography in his work but rather the atmosphere that dominates in The Singer. I can sense the same deep, deep melancholy that radiates from the singer’s closed mouth and each crease of her dress that I usually experience when I look at any of Munch’s works. Furthermore, we could mention the theme of a woman as a femme fatale, a quasi-picture creature with a strange but fascinating connection with nature and spirituality that enthralled men of the time.

However, I couldn’t find any date or exhibition that would confirm that Kandinsky had ever seen any of Munch’s works. In 1902 Kandinsky was studying art in Munich, while Munch was invited the same year to display his works at the hall of the Berlin Secession. Is it possible that Kandinsky travelled to Berlin to see it? Who knows…

In 1922, Walter Gropius appointed Kandinsky the director of the wall painting workshop at the Bauhaus Weimar, where he remained until 1925. Then, in Dessau, he taught classes on abstract form elements and analytical drawing in the preliminary course until 1932. Together with Alexej Jawlensky, Paul Klee, and Lyonel Feininger, he founded the artists’ association Die Blaue Vier (The Blue Four) in 1924.

While at Bauhaus in Dessau, he became a neighbor to Paul Klee and the changes in Kandinsky’s style and color scheme can be attributed to his influence. They lived side-by-side in two semi-detached masters’ houses and often socialized together with their wives, or took long walks in the valley of the Elbe river. Kandinsky and Klee had known each other for years by then, as they met in 1911 when they were living on the same street in the artists’ quarter of Schwabing. The two were labeled by the Nazi regime as “degenerate” and soon needed to flee Germany. Klee moved to his hometown of Bern in neutral Switzerland and Kandinsky to Paris, but they kept in touch regularly writing letters.

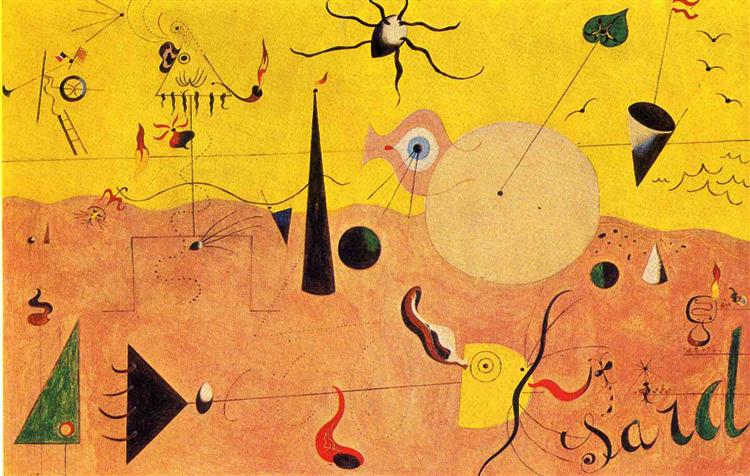

When Kandinsky heard that his works from the final phase of his activity (called “biomorphic” by critics because they were inspired by nature and Ernst Haeckel’s book Kunstformen der Natur) were compared to Surrealist paintings by Joan Miró, he was furious. “I’m not a Surrealist!” he screamed. He didn’t even like to call his art simply abstract but instead, he proposed his own term: abstract concrete art. This was to make it clear that although his paintings were not figurative, they were still deeply ingrained in reality.

Whatever he’d said, the resemblance between the two is pretty obvious. Yet, Kandinsky’s inspiration was totally different; Miró explored the realms of dreams and the subconscious, Kandinsky the natural world. Both explorations led them to the same destination: abstraction, which would soon dominate art for the rest of the century.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!