Willem de Kooning in 5 Works: A Look at the Abstract Expressionist Master

Willem de Kooning was a pivotal figure in 20th-century art and a leading force in Abstract Expressionism. His dynamic brushwork, complex...

Carlotta Mazzoli 18 July 2024

2 November 2023 min Read

It’s often the men of Abstract Expressionism who are best known: Jackson Pollock and his famous “drip” technique; Willem de Kooning’s abstract women; Mark Rothko’s colorful rectangles. Yet it’s Frankenthaler who, after seeing what Pollock was doing, decided to create something revolutionary herself, the “soak-stain” method of painting.

Born in 1928 to wealthy German-Jewish immigrants (her father was a New York State Supreme Court judge) Frankenthaler was the youngest of three girls. Rather than embrace the “country club” world of her family by attending Vassar or Mount Holyoke like her older sisters, Frankenthaler decided to study painting at Bennington, a rather scandalous thing for a girl from the Upper East Side to do in 1946. The self-proclaimed lover of “Bohemia” became a major player in the Abstract Expressionist art movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Frankenthaler once declared:

A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once.

Helen Frankenthaler, This is Tomorrow.

On a whim one day, Frankenthaler thinned her oil paints to a liquid and then flooded her unfinished canvas. The paint soaked into the fabric, pooling and layering, creating and recreating brilliant colors until it looked less like an oil painting and more like a watercolor. Thus, the “soak-stain” method was born. She called the work Mountains and Sea (1952). Art critic Hilton Kramer once described it as important to the Color Field School as Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon was to Cubism. Or as MoMA Curator Emeritus John Elderfield once wrote about her work, “It was as if the color and the surface were one thing…”

It’s not only the bright colors that make Frankenthaler’s work so mesmerizing. I love her teasing titles, which provide the viewer something tangible to hold onto amidst the abstraction. There’s Rapunzel from 1974. My favorite is the whimsical Flirt, created in 1995 when Frankenthaler was 67 years old.

In Jacob’s Ladder, for example, there isn’t an identifiable ladder, but through the use of color and the thinnest of lines, Frankenthaler creates vertical movement as well as a sense of teetering unbalance. In the Biblical story with the same name, Jacob dreams of a ladder, where angels move seamlessly between Heaven and Earth. At this point in her art career, Frankenthaler was already a pro at straddling two worlds, tirelessly ascending the art ladder in a world not inclined to welcome women.

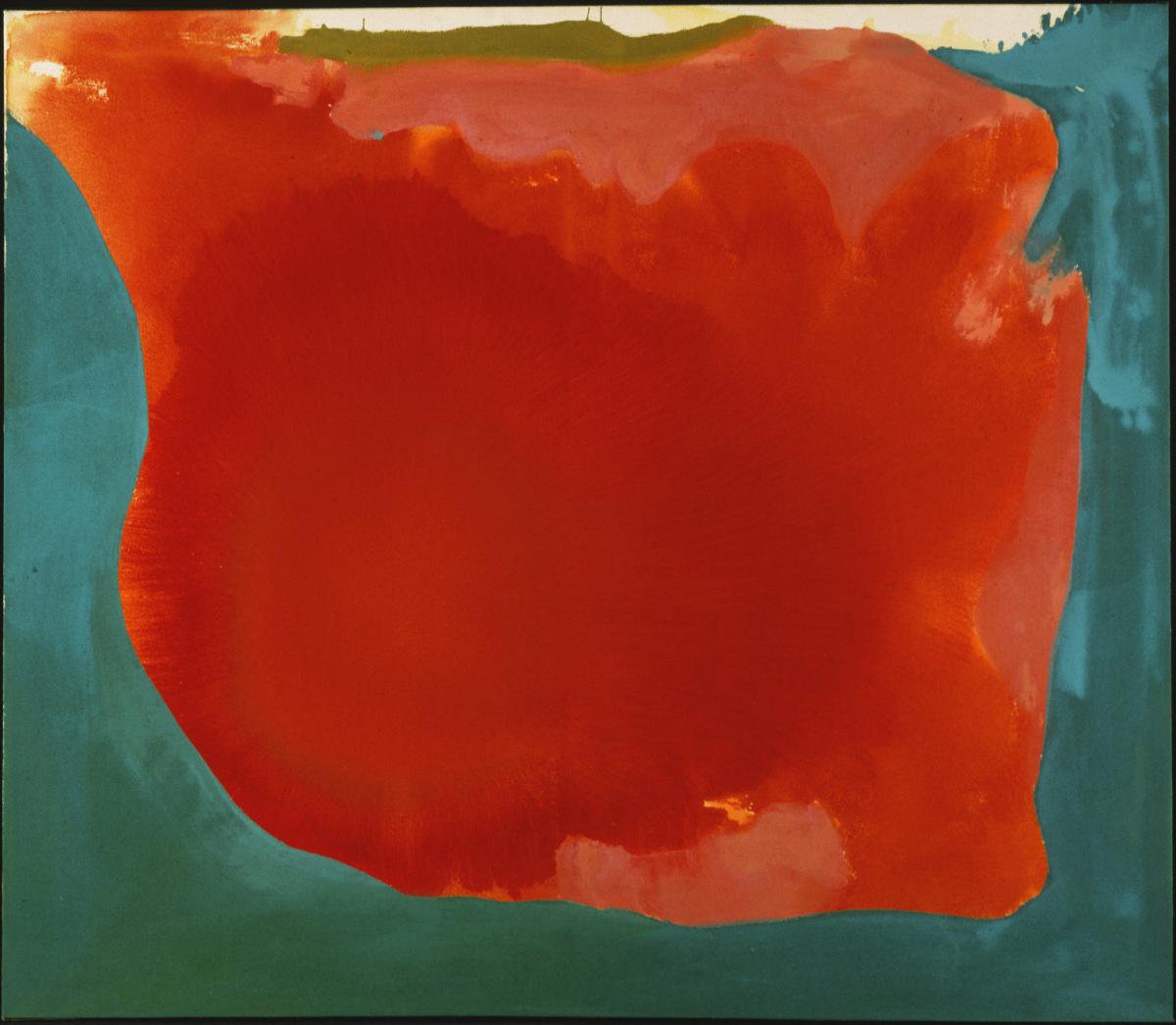

Throughout her six-decade-long career, Frankenthaler often returned to the natural world for inspiration. She studied 19th century landscape painters and the titles of many of her paintings evoke nature. With Canyon in 1965, Frankenthaler went from oil to acrylics, whose thinning created more defined edges, more saturated colors. It’s a canyon, of course. But it’s so much more – it’s also an explosion of color, contrasts, and curves.

I think of her in 1952 at age 23, only a year after her first solo show, crouching on the floor next to an unfinished canvas, translucent oil paint in one hand, wondering, “What if?” and how, with that first splash of color, Frankenthaler transformed the world we thought we knew into something more daring, more colorful, and frankly more interesting.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!