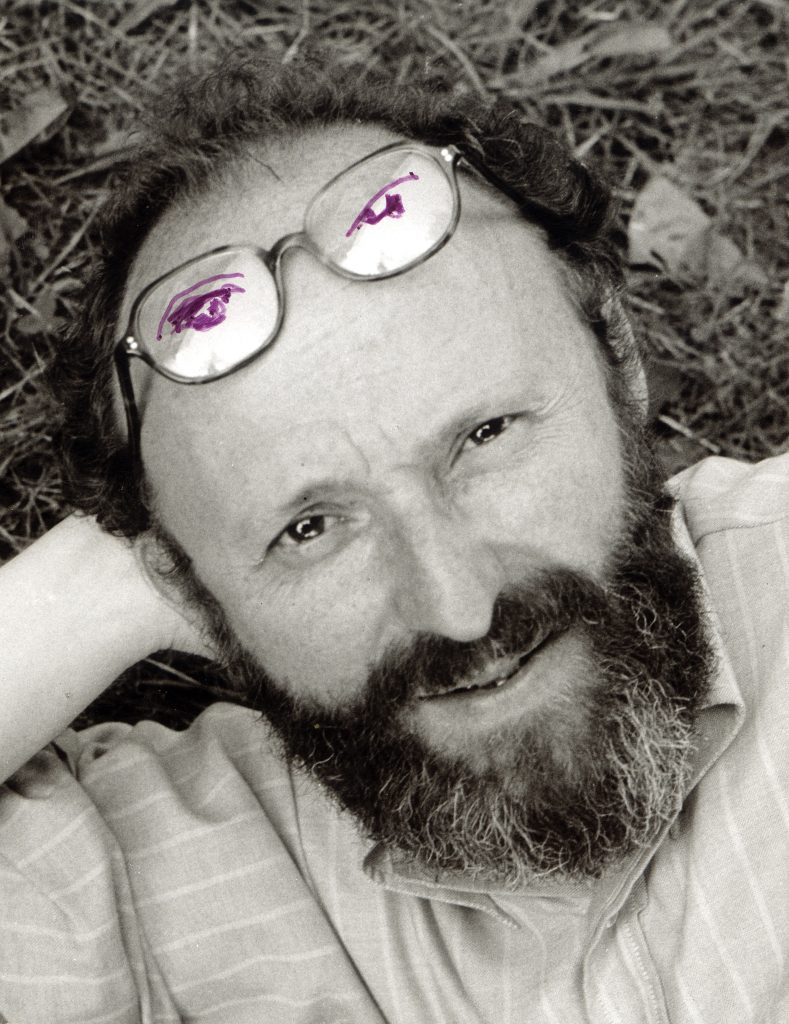

It’s fascinating to consider the way art can inspire and connect people across decades and movements. In 1977, while studying at the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh, the then 19–year-old, Keith Haring, with one of his childhood friends, by chance visited the Museum of Art at the Carnegie Institute, where he encountered a retrospective of Pierre Alechinsky, a key figure and one of the still-living CoBrA art movement founders.

CoBrA, an acronym for the three capital cities in which its founding members originated: Copenhagen (Denmark), Brussels (Belgium), and Amsterdam (the Netherlands) represented the international, interdisciplinary, and collective art movement that spanned from 1948 to 1951. NSU Art Museum has the largest collection of CoBrA art in the United States.

All the CoBrA artists lived in the post-war era and their art was considered degenerative. They looked to subvert the consumerism of art and they collaborated in singular paintings as they believed that one painting has no singular master. Being activists also, they brought these post-war concepts and a sense of optimism in their art outside the western tradition.

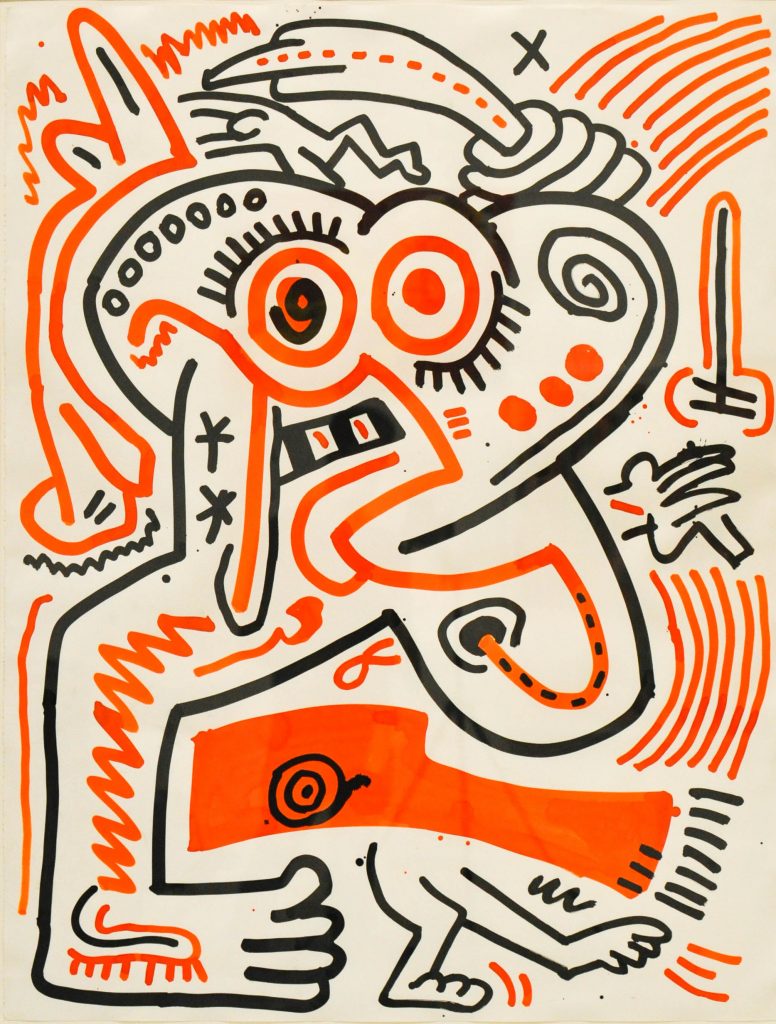

When Haring saw this exhibition at Carnegie’s it was a crystalizing moment for him. He was completely absorbed and inspired by the scale of Alechinsky’s work, by the calligraphic expression and overall exuberant abstraction. Throughout Haring’s renowned career, he would credit the experience of seeing Alechinsky’s work at the Carnegie as a watershed moment for him as an artist, even though the very first time he saw Alechinsky’s works at the retrospective he had never heard of the artist before.

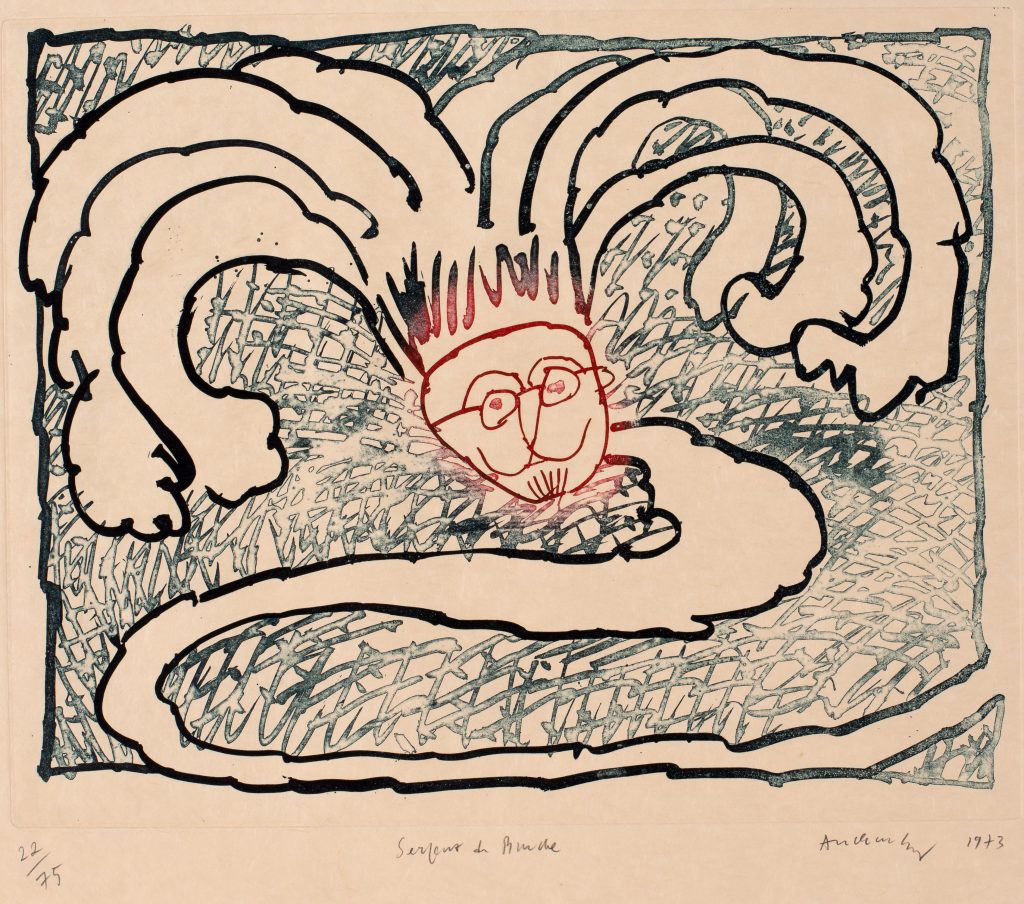

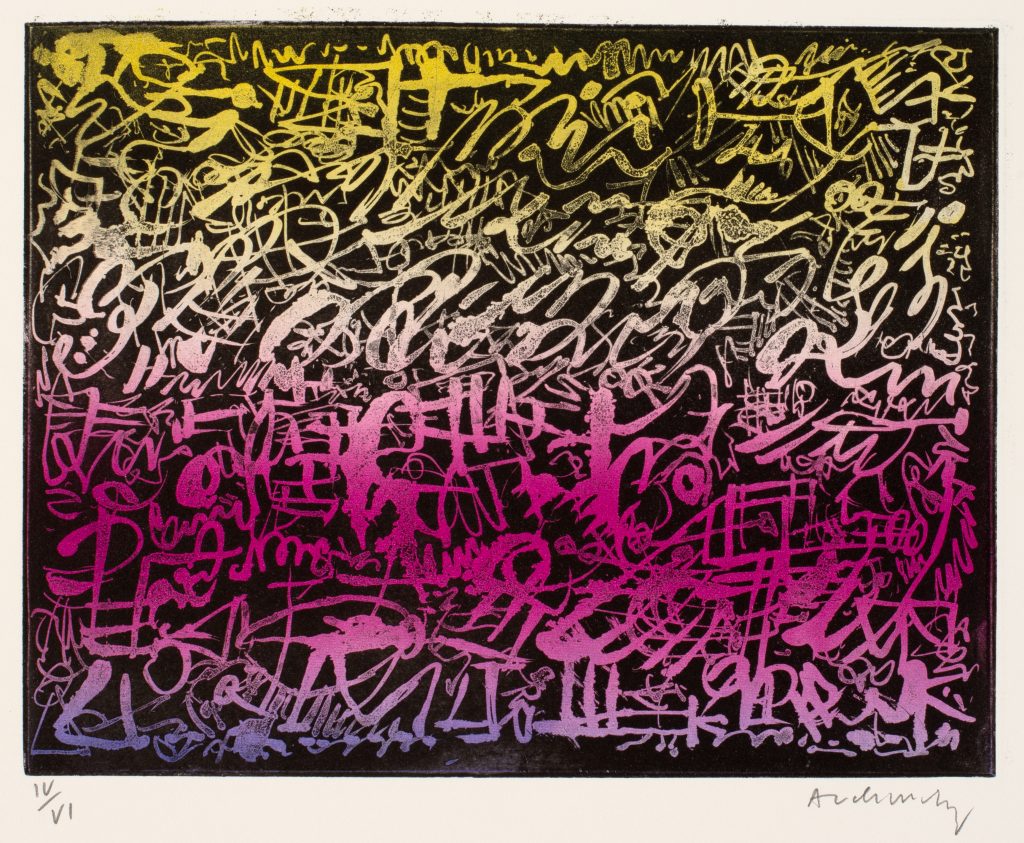

Haring studied all the Japanese, Sumi, and Ink artists in the videos made by Alechinsky, and in interviews he would repeatedly describe the sudden “rush of confidence” he had when he saw Alechinsky’s self-generating shapes and framing devices, which were so similar to his own but had been realized on a monumental scale.

Alechinsky’s expressive and spontaneous lines thrilled Haring, who returned to the exhibition multiple times, studied the exhibition catalog, read Alechinsky’s writings, and watched films of him painting enormous canvases on the floor. Haring immediately started working bigger, painting horizontally and incorporating spontaneous drips into his compositions like Jackson Pollock. While Haring maintained a controlled line that was less fluid than Alechinsky’s, this encounter assured him that he was “doing something that was worthwhile.”

The inspiration that Haring derived from Alechinsky early in his career remained a constant throughout his life. In the 1980s, Haring visited Alechinsky at his studio in Bougival, France; this experience is preserved through artworks they traded and a forthcoming testimonial written by Alechinsky on the occasion of this exhibition.

Both artists preferred drawing on paper rather than using canvas, Pierre Alechinsky taught Haring his technique, which he subsequently used throughout his career. As Alechinsky worked a lot with children, he had the idea of creating images that could communicate with a wider audience. Haring was fascinated that his art was a combination of children’s art, pictographs, and simple forms. By furthering his own practice, he was trying to find a symbolic language that would be universal, to reach the wide public outside the walls of the gallery in the same way as Alechinsky did. But many times he also left the viewer to have a personal interpretation. There was universality but also openness to interpretation.

Another parallel between the two artists is that they were both involved in music, jazz music particularly. Haring, as well as CoBrA, crossed disciplines in music and dance, and this acoustic world transcended into their art.

So to be said, Keith Haring was extremely productive and prolific throughout his life. He thrived on inspiration from well-known artists such as Jean Dubuffet, Wassily Kandinsky, Christo, Jean-Michel Basquiat and we can see many references also of James Ensor or Jackson Pollock in Haring’s works as well.

Haring was completely touched by the art of Alechinsky and so he absorbed everything from him: calligraphic line, working on paper, or working on a large scale. His aim was to create art that would be brought to a bigger audience: activism and art which would change the world. His artworks in this sense is proof that his legacy comes not only from contemporary American and Graffiti art but drew also from European avant-garde.

In fact, the exhibition at NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale illustrates the affinities between these two artists, not only how they both influenced each other reciprocally, but also how CoBrA influenced American contemporary art and subsequence generations of artists.

So whether you’re nearby or distant, don’t miss the opportunity to visit the exhibition at the NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale until the 2nd of October, and go get absorbed by these two masters!