5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

14 January 2025 min Read

Not many of us have heard of Kiyohara Yukinobu, but we probably should have. She was a Japanese painter in the early Edo period (1603–1868) and one of the most talented artists of the Kāno school.

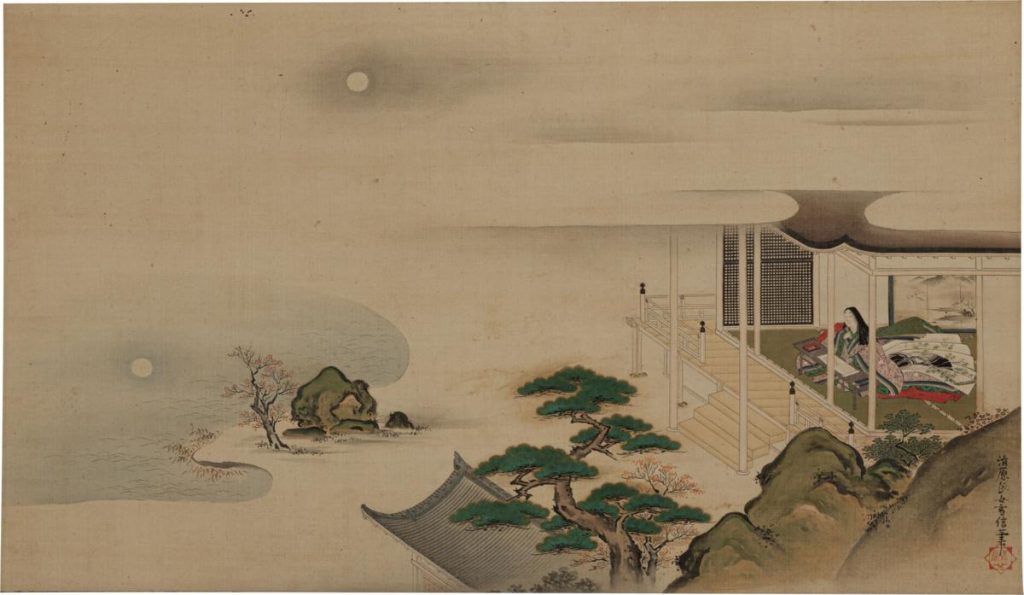

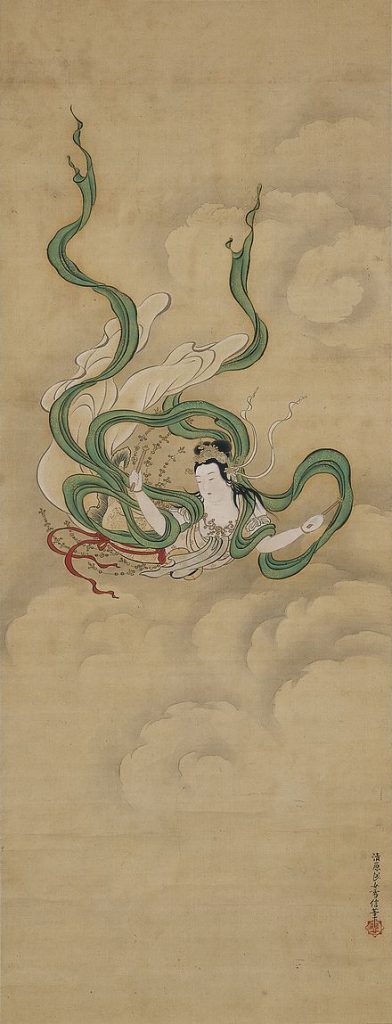

Even if you don’t know her name, you may have seen her painting representing Muraski Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji. Yukinobu depicts the writer Shikibu with a pen in her hand, mid-composition; we are witnessing the genesis of one of the world’s greatest pieces of literature. This is also a picture within a picture: behind the writer hangs a Chinese-style scroll in which a lone figure floats silently across a lake, ringed by misty mountains.

Shikibu is one of the most important figures in Japanese cultural history. The Tale of Genji, written in the 11th century, is one of Japan’s most celebrated works of literature, as well as possibly the first-ever novel. It was written in kana, a phonetic script used by women forbidden from using the Chinese written language. Genji fever gripped its readers who went as far as decorating their houses in Genji-ana style and wearing Genji-style robes. In 1856 Japanese princess Atsu even insisted on a Genji-themed wedding.

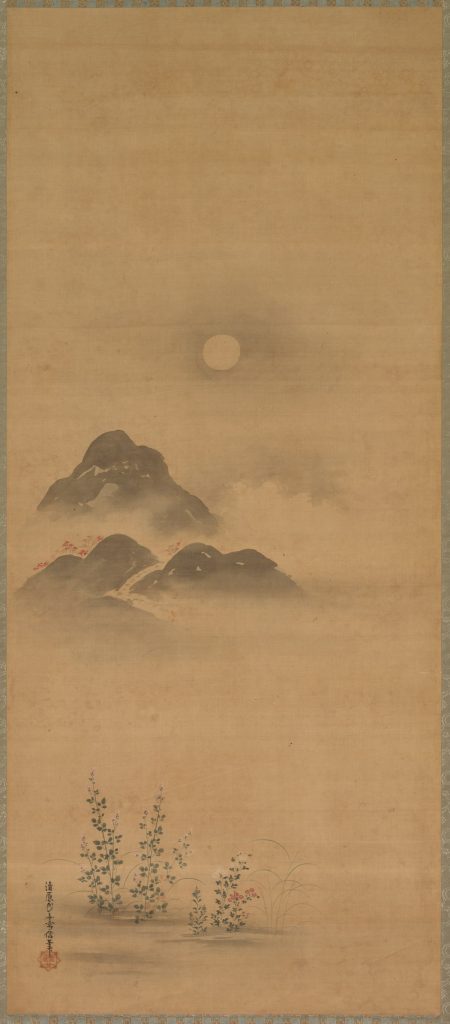

Born in 1643, Yukinobu trained as a Kāno school artist (a painting tradition based on merging the ink and brushwork of Chinese artistic precedents with the color and pattern of Japanese style). Throughout her career, she managed to tread the line between following the traditions of the prestigious school that taught her, while also making each painting very much her own. Melding the traditional with the personal marks Yukinobu as an exceptional artist.

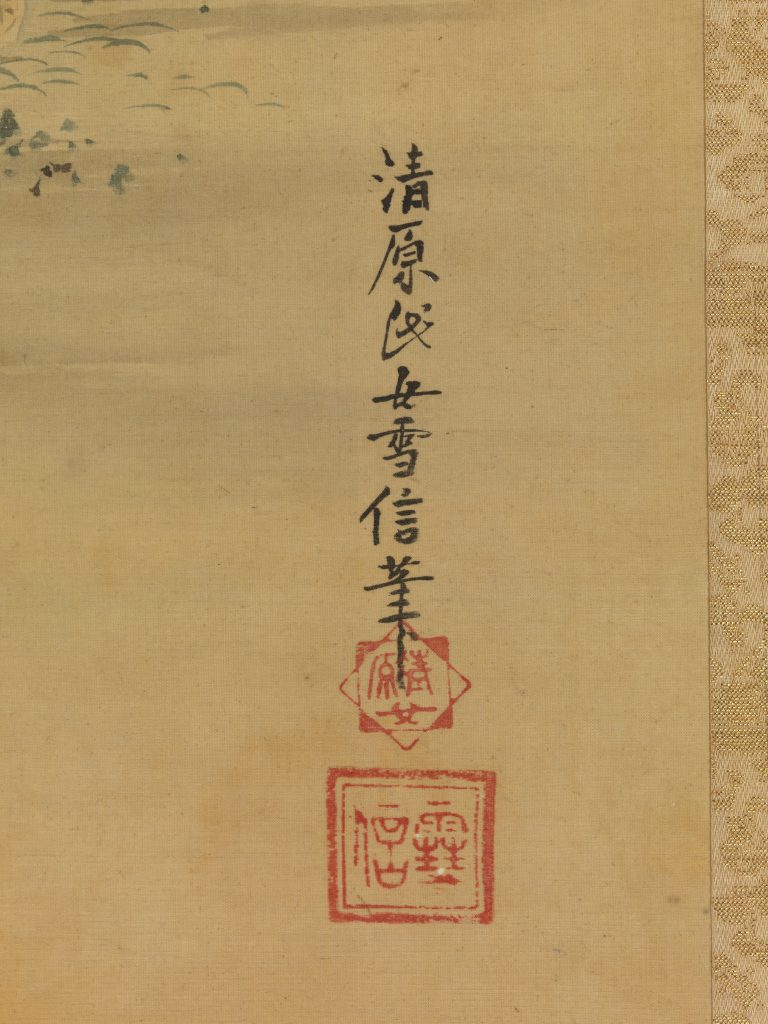

Based in Kyoto, the Kāno school was active between the 15th and 19th centuries. It was a scholarly academy with an aversion to women painters. That we even get to see the wonderful work of Yukinobu is a miracle in itself. Certainly, her paintings are stamped with her name, suggesting that buyers were happy to collect the art of a talented woman. And who bought these paintings? Well, the wealthy classes and business owners, the aristocracy, the samurai, Buddhist monks, and Shinto priests.

At that time, as in the West, women were not encouraged to become working artists. Painting was a desirable hobby for a daughter or a wife, as was music, but it could rarely be a career. Women simply did not have educational opportunities outside of the home. A woman from a high-ranking family would be given brushes and paint as part of her bridal set, her konrei chodo, but this was strictly for use in the privacy of her own home.

However, Yukinobu proved the exception. It helped that she came from a painterly family, connected to the Kāno school of painting. Her mother Kuniko was the niece of Master Kanō Tannyū. Her father Kusumi Morikage was a painter and a disciple of Kanō Tannyū. In fact, it was her father who encouraged and taught Yukinobu, even allowing her to take lessons from other painters.

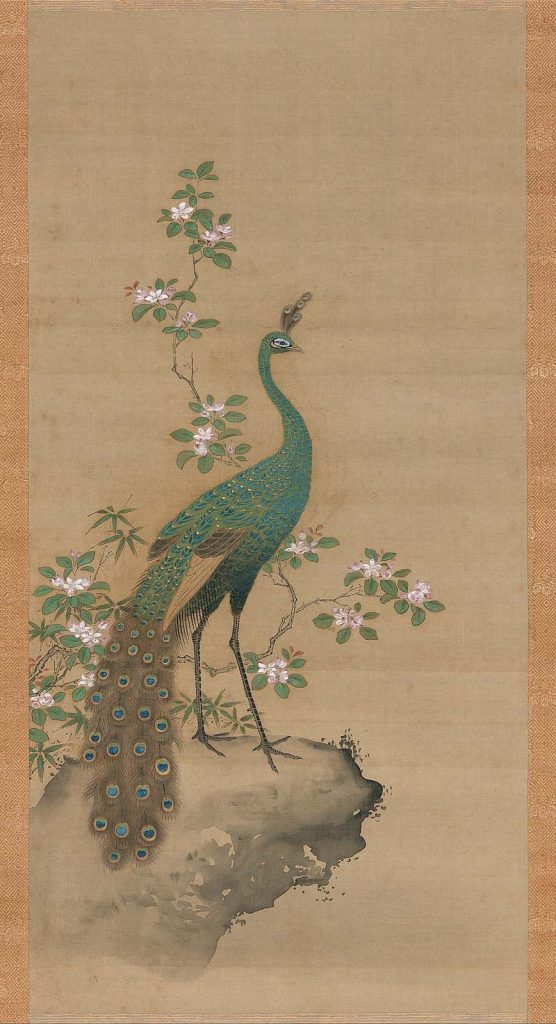

Her art often depicts legendary and historical women, as well as the natural world of her homeland: landscapes, flowers, birds, etc. She used a variety of formats, from small silk rolls to large-scale screens. Her brushwork is exacting and exquisite, with meticulous detail. Ink tones and gold leaf blend with vibrant colors which dress the seasons elegantly.

Yukinobu lived and worked in Kyoto for most of her life. She married a fellow Kāno school student called Kiyohara Hirano Morikiyo. She died in 1682, aged just 39. A pioneer in a male-dominated profession, we know very little of her day-to-day life and it is difficult to find biographies and descriptions of Yukinobu’s work. But, we are at least left with the delicate artifacts of her work, which are simply sublime!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!