Let’s play a game: pick up any magazine from a US newsstand and count how many people of color are featured. Now try playing with a magazine from the 1950s.

Depending on which magazine you chose, the difference may not be all that striking. But the fact that there is increased representation of the different looks of beauty in the US is due in no small part to Kwame Brathwaite (b. 1938), the photographer behind the “Black Is Beautiful” movement of the 1960s.

Brathwaite began his work in New York, capturing the electric energy of the Harlem jazz scene with 12-shot rolls of film. The Skirball’s exhibit is accompanied by a playlist of jazz, blues, and soul, reflecting the fusion of Harlem’s art and music scenes, and Brathwaite’s role in both. In 1956, Brathwaite co-founded the African Jazz-Art Society and Studios (AJASS), a cultural collective of artists, writers, and musicians. At the time, black jazz musicians’ album covers often featured images of insipid white couples to market the music to white audiences. Brathwaite’s photography would soon change that, featuring artists like Nina Simone, James Brown, and Diana Ross on their own albums.

The images of Emmett Till’s brutal murder galvanized Brathwaite and awakened him to the power of photography in political protest. Influenced by contemporary black nationalists Carlos Cooks and Marcus Garvey, Brathwaite aimed to encourage others to reclaim a lost African heritage, instill pride in natural hair and all shades of skin, and reject efforts to conform to white ideals of beauty. His casual images of black individuals, communities, and businesses also exemplified his activism in the “Think Black” and “Buy Black” movements. Brathwaite saw the importance of valuing and visualizing the community, especially when beset by racism and violent policing. His subjects are presented as complex, real, and vital in a culture that so often reduced them to stereotypes. The everyday images drive home how important it is to see yourself represented, and how damaging it is not to.

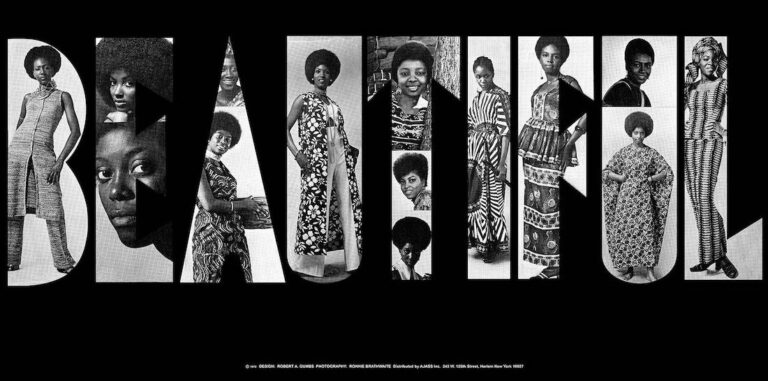

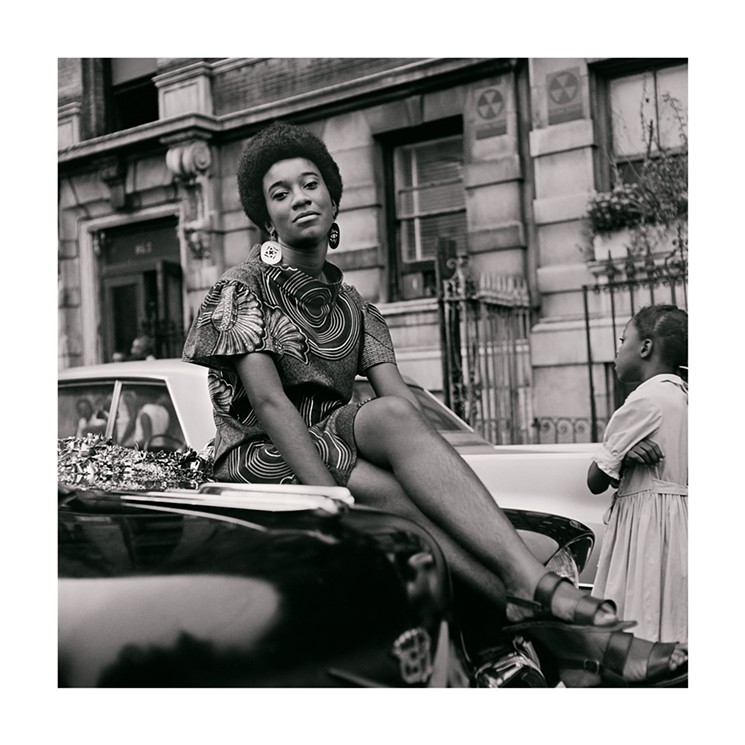

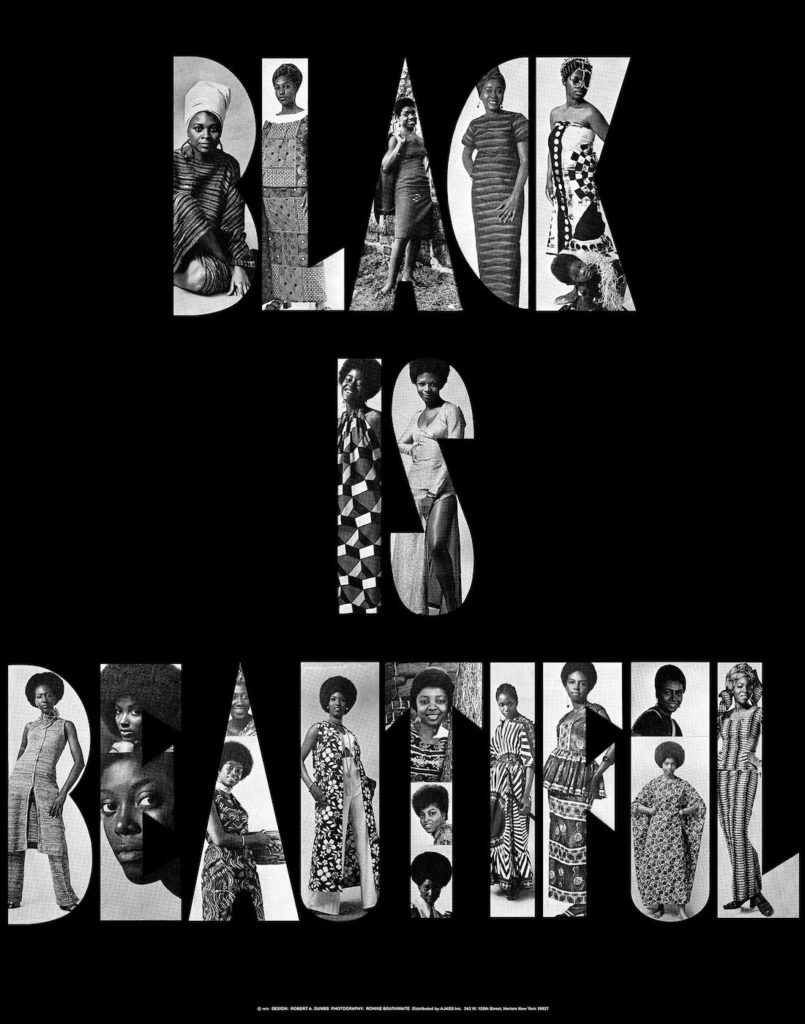

To counter the pale, frail beauty standards set by 1960’s models like Twiggy, Brathwaite co-founded an annual Afrocentric fashion show, the first of which was called “Naturally ‘62 – The Original African Coiffure and Fashion Extravaganza Designed to Restore Our Racial Pride and Standards.” He also started the Grandassa Models, a modeling group for black women. With varied skin tones, natural hairstyles, and African-inspired fashions, the models promoted a wider definition of beauty. Brathwaite’s goal – to express pride in natural beauty and blackness – speaks loudly from each glamorous image in the exhibit. His impressive range traverses highly stylized fashion portraits and intimate, behind-the-scenes shots, always conveying a sense of dignity and deep interest.

Two standout photos show women and men standing in a public school yard, grouped by gender in separate photographs. They could almost be speaking to each other or facing off in an unspoken power contest. The dynamic between the two images, and the clear strength and pride in the models’ looks and stances, make this the most compelling corner of the exhibit.

While Brathwaite’s art is powerful on its own, his collaborations with others put multiple art forms – music, photography, and fashion – to a common purpose. The exhibit nicely integrates these, displaying some exquisite examples of the Grandassa models’ self-designed clothing and jewelry along with Brathwaite-designed record covers.

The power of Black Is Beautiful is in its simplicity. Black Is Beautiful should not be a radical statement, yet it was and is. Just like Black Lives Matter. These mantras are reminders of what white culture takes for granted: that white skin is beautiful and that white lives matter. The latter ideas are so ingrained in American culture that they don’t need saying – but the same is not true for the black phrases. They are necessary because things were not, and are not, equal. Exhibits and careers like Brathwaite’s are urgent, appealing reminders of how far we’ve come and how far we still need to go.

Black is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite

Organized by Aperture Foundation, New York, and Kwame S. Brathwaite.

Till September 1, 2019

Admission: $12 adult, $9 concession, $7 children under 12 (free on Thursdays)

Skirball Center

2701 N. Sepulveda Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA

Further Reading:

Monograph published by Aperture

Anne Wallentine is a freelance writer with an MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art. Her art history background also informs her role as a creative director for PR and design projects. She is particularly interested in feminist and queer history, Japonisme in American woodblock prints, the politics of Northern Renaissance portraiture, and tracking down the next best coffee or gin.