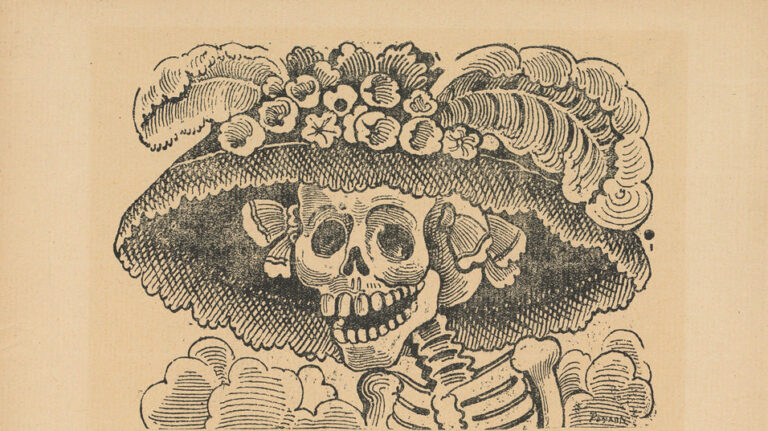

We all know Coco, a Pixar animation about a boy who dreams of becoming a musician, so he enters a talent contest, suddenly disappears from this world and finds himself in the after life, among the dead. It received a Golden Globe in the Best Animated Feature movie category in 2018. In regular or fancy clothes, the skeleton characters used in the film are inspired by the prints by José Guadalupe Posada, especially by his most renowned creation: Catrina La Calavera Garbancera. Or, more colloquially known as La Calavera Catrina.

José Guadalupe Posada (1851–1913) is often regarded as the father of Mexican printmaking and the best caricaturist. During his long career, he created images for local printing houses and numerous religious publications. To this day, he is a cherished political satirist and critical narrator of the Pofiriato dictatorship, its economic, social inequalities and violent politics.

In 1868, Posada learned lithography while working as an illustrator in the workshop of José Trinidad Pedroza in Aguascalientes (central Mexico). At this workshop Posada debuted and illustrated his first political cartoons for the publication: El Jicote. Later, Posada had few litography workshops, first in Aguascalientes, second in León, Guanajuato, and a final in Mexico City (at Calle Cerrada de Santa Teresa in the city center).

Possibly as early as 1889, Posada began working for the publishing house of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo based in Mexico City (1852-1917). Many of the works that were kept to our days come from this printing firm.

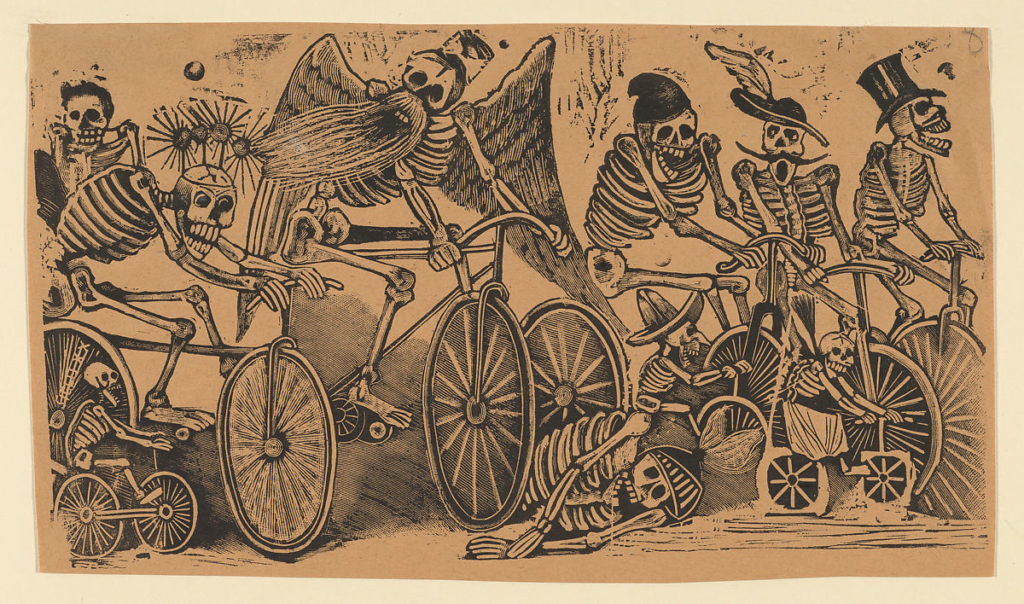

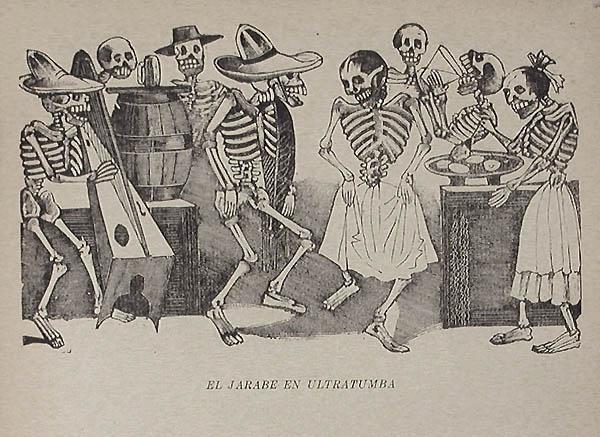

Posada’s best-known caricatures are of skeletons (calaveras) published on brightly-colored papers. They were a way to address topical issues and current events, love and romance, stories, popular songs, and other themes, in the press where only 30% of the society was literate. The comics were easier to convey complex topics with fewer sentences, so they were more accessible. They were printed to be sold by street vendors in markets, on the street, and at festivals, and designed to be vehicles for telling stories to the masses. Posada’s works criticized the situation in the country and that of the most privileged classes. He evidenced the terrible inequality and injustice that existed in the Porfiriato.

La Catrina is believed to have first appeared around 1912 just a few months before Posada’s death. The earliest known use is from 1913, likely published about eight months after Posada’s death.

Who Named Her Catrina?

La Calavera Garbancera would become Posada’s most popular character. What does her name mean? Calavera is a Spanish term for skull. The garbancero (chickpea) was a slang word used to call derogatively a person who, despite having indigenous blood, pretended to be European or who denied his or her own cultural origin. Posada made fun of these people in his satirical caricatures. “Catrín” used to mean an elegant and well-dressed man, usually someone who followed the European fashion, instead of local. Catrín was also used to portray members of the Mexican aristocracy of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Mexico as out of touch with the Mexican reality and focused on foreign ways of life, primarily French or American. Diego Rivera named the female skeleton in a huge hat: La Catrina.

New Life as a Symbol

Diego Rivera appropriated her image in the mural Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (painted between 1946 and 1947) in the hotel del Prado, located on Avenida Juarez in El Centro Historico of Mexico City. The work is enormous: it measures 4.8 height and 15 width.

The painting gathers, in one set, the Mexican historical figures from different epochs in an actual park called Alameda, which is located near the old city in the country’s capital. It is both surrealist and deeply symbolic. It equals politicians of different philosophical convictions: revolutionaries, dictators, positivists, democrats, liberals and conservatives, indigenistas.

The scene is crowded and dense. The work, like death, unites people from different walks of life and periods: heroes and villains, winners and losers, generals and politicians, campesinos (agricultural workers) and hacendados (plantation owners), kids and adults, writers and beggers, aristocracy and proletariat, real and imaginary figures.

Its composition recalls Rembrandt’s Night Watch. It is more dynamic and dramatic on both peripheries, and focuses our sight to the center on La Catrina holding the hand of a young Diego Rivera. Next to Calavera, on the left, is Frida Khalo. To the right José Guadalupe Posada himself.

Catrina wears a fashionable dress, a hat with big feathers, and an elaborate boa—reminiscent of the feathered Mesoamerican serpent god Quetzalcóatl—around her neck. She wears, though she does not have eyes. Her belt also alludes to another pre-Columbian artifact – Aztec stone calendars.

It seems that Rivera pays homage to Posada with this painting. He places the image of Catrina in his very particular vision of Mexican identity. By doing so, he takes a historical cartoon and transforms it into a national symbol the very Mexican belief that in death we are all equal. He gives commentary to the past and present, as Posada did.

Day of the Dead and Catrina Today

The pop culture in Mexico took Catrina and made it an omnipresent commodity, especially during the Day of the Dead festivities (2nd of November). Her image now transcends borders and mediums. She is a glamorized, Hollywood-appropriate character or a sweet souvenir easily available at the local market. We can consume her literally, or on Netflix.

Regardless of her globalization and commodification, this image and the whole of Posada’s visual language remains profoundly universal as it refers to human existence. At the same time, it could only be created in a country of Mictlantecuhtli (Lady of the Dead), goddess of the underworld, who rules over the afterlife and whose role is to watch over the bones and preside over the ancient festivals of the dead. In Mexico, death is familiarized in culture through the centuries, her depictions could be found on ancient buildings and Aztec codices. Posada brings with Catrina yet another version of the death. He, like the indigenous artists, shows that she is a part of life, “death is democratic, since after all, blondes, brunettes, rich or poor, all people end up being skulls.”