The subject

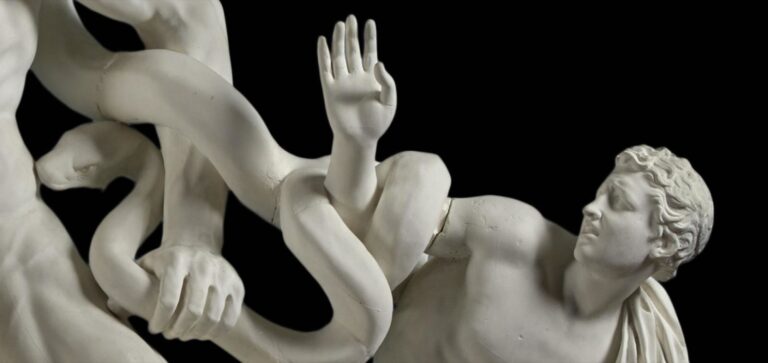

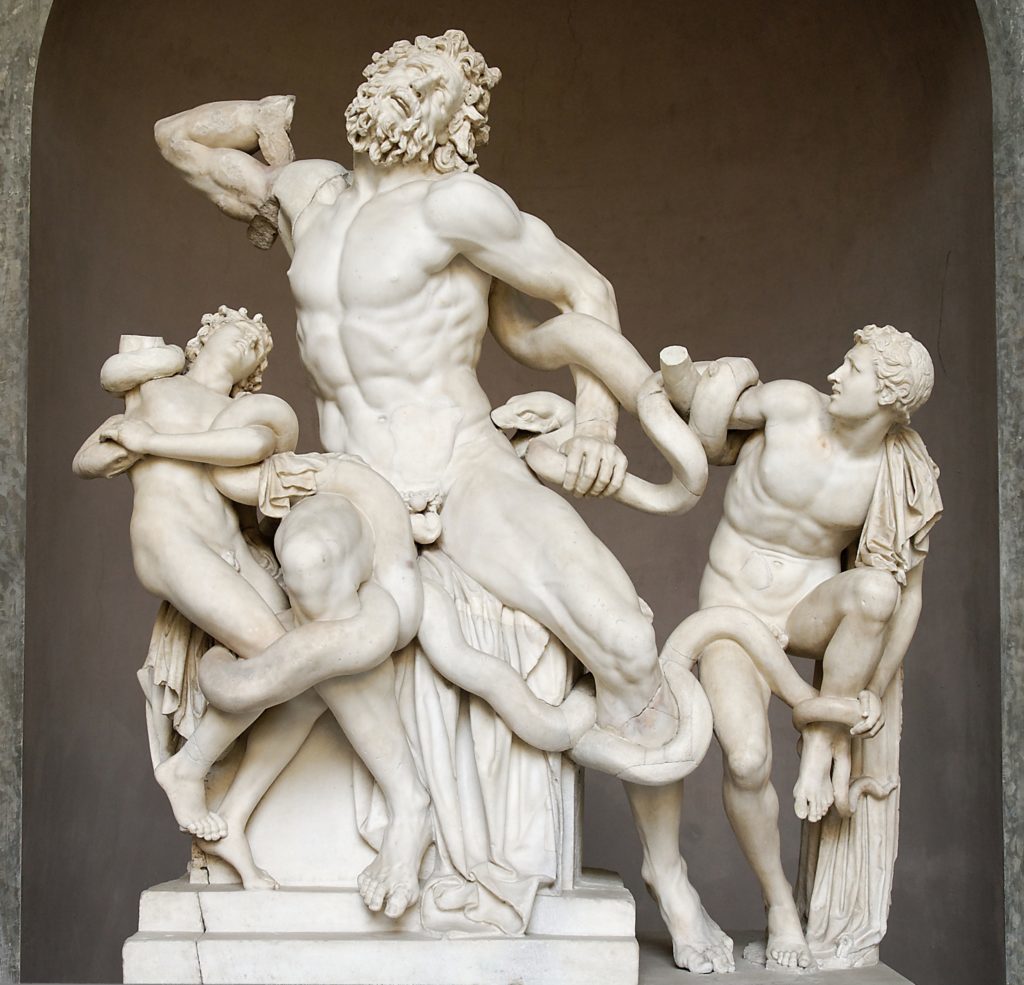

The statue “Laocoon and his sons”, attributed to Greek sculptors Agesander, Athenodorus and Polydorus, has fascinated Frederick Schiller since his early adulthood.

It represents mankind (father and sons, adult and youngsters, present and future) being mercilessly struck by torment and death instilled in it by the two snakes. The father shows a daunting courage by fighting the snakes in order to save his sons. The two sons, paralyzed by anxiety, express only fear and fatality. This dramatic subject is lingering all through Schiller’s works. He took the highly emotional example of Laocoön to produce compelling dramas (William Tell among others), but also to find the means for tackling and conquering the dark works of torment and death (in his essays on the Sublime in particular). Laocoön, indeed, conveys a message that represents the work of a lifetime.

The incredible power of the Laocoön statue is, first of all, produced by sculpture, the medium chosen by the artists. Among the Arts, only sculpture can produce objects with real-life volume which can be touched and felt with the hands. The projection and identification of the viewer are even more strengthened in human status because of this volume. This volume enhances, hence, the connection, the emotional effects of the created image.

Schiller first mentioned Laocoön in 1785 in his “Letter from a traveling Dane”, a writing which is a captivating invitation to appreciate the statues of the Ancient World.

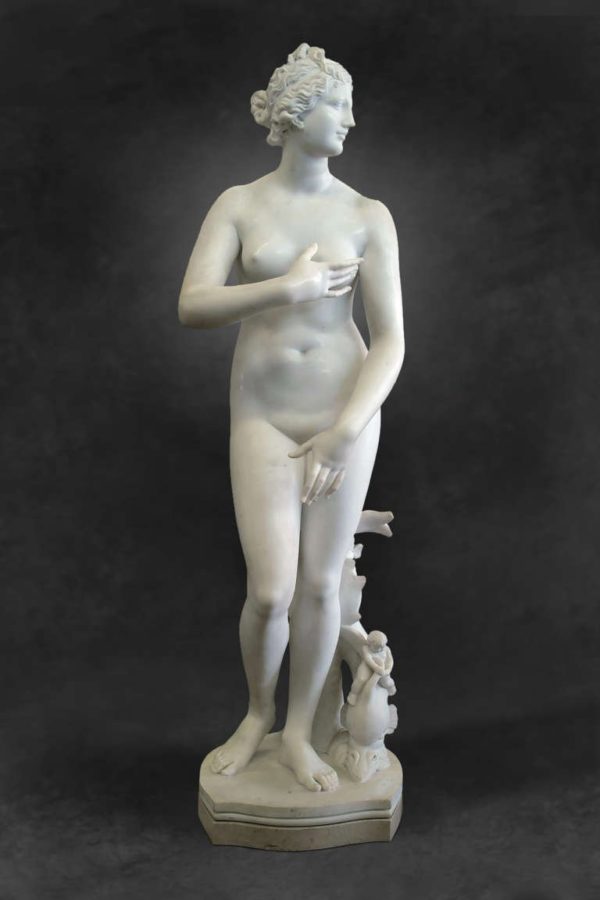

The sculpture is also reproducing Nature, idealized by man

Greek sculpture, like any form of sculpture, symbolizes human taming Nature by chiselling and polishing the rough stone or marble. It is also the very act of man projecting and finding himself in Nature but in a more perfect version. This is especially true with human statues.

Schiller maybe was fascinated by sculpture because, in his childhood, he was fully impregnated with Christian (Lutheran) teachings in which Bible, erecting and admiring statues is not recommended. Once grown up, he must have been curious about looking at statues.

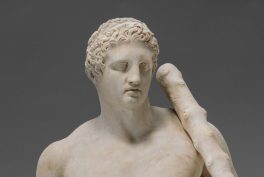

Hence, Schiller’s “Letter from a traveling Dane” could represent a transgression or liberation. The keen interest is displayed in his descriptions of bulging musculature, expressive facial features and overall aesthetic value in masterpieces like the Farnese Hercules, Medici Venus or simply the Torso.

The following excerpt from this letter gives us an idea of his fascination with the beauty emanating from statues:

The Vatican Apollo represents the most charming figure of a young man who is precisely at the point of turning himself into a man; lightness, freedom, body fullness and the purest harmony of all the parts united into an inimitable whole, declare him to be the first of the mortals, the head and the neck reveal a god.

The man and his work

The symbolic of sculpture and the sculptor would become very strong in his works as he progressed in life. Just like the sculptor carving out an ideal human image from the rough marble, the human being works on himself to produce his best version. Part of the work is learning to deal with the phenomenon illustrated by Laocoön.

Regardless of their specific themes or expressions, the Greek sculptors’ statues convey overall the following message: I am not perfect yet (I am still working on myself) but some of my works can already reach perfection. Schiller reflected this frame of mind (from the statues) onto his works.

Hence, he finishes this letter with these lines exalting the hope provided by daily actions:

Creating something that will not perish, something that will live on even when everything else would have been wiped out! O friend! I cannot impose myself onto posterity through obelisks, or conquered lands, or discovered new worlds! Cannot make posterity remember me through a masterpiece! Cannot create a head for this Torso! But perhaps I can still do a good deed without requiring the presence of witnesses!

Later on in his “Letters on the aesthetic education of the human being”, he will summarize this symbolic of man ever working on his nature silently, without fanfare with the following:

He (the human being) is the work, and the work is his.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”B00OZQAYSI” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/61qzf02BtXL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”105″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”B00P5ZD6YM” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/61E1nTxBZnL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”105″]