5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

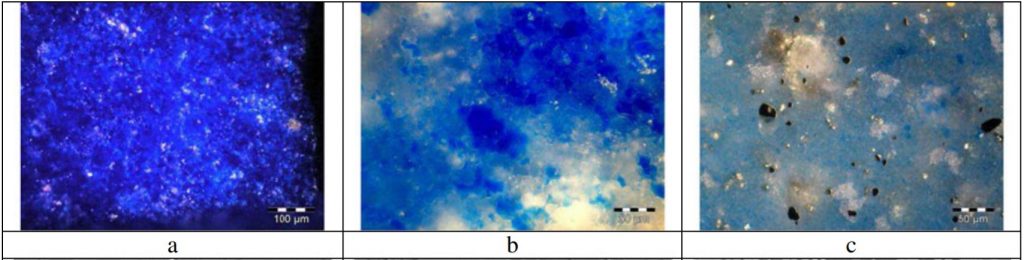

Lapis lazuli, once more precious than gold, has a history of over 9000 years. The earliest artifacts found at Bhirrana, which is the oldest site of the Indus Valley civilization, date back to 7570 BCE. Nowadays, it is still being used in the art world for pigments used in restoration works.

Lapis is the Latin word for “stone” and lazuli is the genitive form of the medieval Latin lazulum, taken from the Persian lājevard that means “sky” or “heaven”. Lazulum was used as the root for the word, blue, in most Latin languages: azul in Spanish, azur in French, azuriu in Romanian.

For centuries, the main source of lapis lazuli has been Afghanistan. It was mined in the Sar-i Sang mines, in Shortugai, and in other mines in Badakhshan province as early as the 7th millennium BCE. This source is still mined nowadays with very rudimentary methods and in very dangerous conditions. Add to this the geopolitical context in the area, and you will understand why good-quality Afghan lapis lazuli is still expensive. When Marco Polo visited the place once, he wrote, “There is a mountain in that region where the finest azure [lapis lazuli] in the world is found. It appears in veins like silver streaks.”

The other major deposits of lapis lazuli are in the Andes in Chile, and to the west of Lake Baikal in Siberia, Russia. Nonetheless, Afghan Lapis remains the best, due to greater concentrations of lazurite, which is a blue feldspathoid silicate mineral. Most lapis lazuli also contains calcite (the white vines), sodalite (blue), and pyrite (gold-like metallic bites).

The first documented use of lapis lazuli as a pigment was in the cave paintings in the 6th and 7th centuries CE in Afghanistan and Buddhist temples near the Lapis mine of Badakshan.

The use of lapis lazuli dates back to the Neolithic age when, after being extracted from the mines in Afghanistan, was exported to the Mediterranean world and South Asia along the ancient trade route between Afghanistan and the Indus Valley. Lapis was used since Sumerian (c. 4500–c. 1900 BCE) times for different types of artifacts like seals, jewelry, and sculptures.

The Egyptian world was fascinated by lapis lazuli, not only for its beauty but also because it was believed to lead the soul into immortality and open the heart to love. It was said to contain the soul of the gods. Probably for this very reason, it was used in the funeral mask of Tutankhamun (1341–1323 BCE).

Lapis lazuli was a key to spiritual attainment; enhancing dreams and metaphysical abilities, it facilitated spiritual journeying and stimulates personal and spiritual power. This is why they used it for amulets and ornaments, such as in scarabs. Lapis jewelry has been found at excavations of the site Naqada in Egypt. Legends say that Cleopatra herself used powdered lapis lazuli as eyeshadow.

Lapis lazuli has also been identified in Chinese paintings from the 10th and 11th centuries, and later also in Japanese woodblock printing, where it has been used up to the beginning of the 20th century.

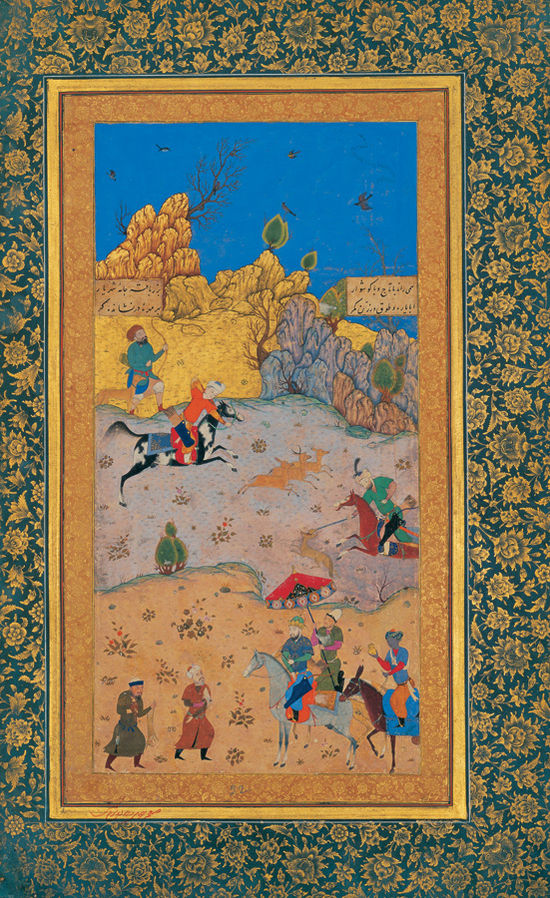

The use of lapis lazuli as a pigment was determined in Mughal paintings. This is a South Asian painting style, particularly from what is now India and Pakistan. These images adorned miniatures, either book illustrations or single works to be kept in albums. It developed in the court of the Mughal Empire from the 16th to 18th centuries. The Mughal emperors were Muslims and they are credited with consolidating Islam in South Asia. Subjects are rich in variety and include portraits, events, and scenes from court life, wildlife and hunting scenes, and illustrations of battles.

As you might have noticed, I have mentioned only its use in the eastern world. In the west, in Paleolithic and Neolithic, the preferred colors were red and black. White has been added to the two by the ancient Greeks and Romans. The reason for that is the Westerners underappreciated any blue object that reminded them of barbarism. The Celts used to decorate their bodies with blue pigment tattoos. It was the color of danger and death. In ancient Rome, blue clothes evoked mourning and grief.

The shift happened in the 12th century, thanks to the French Abbot Suger. He was an important figure in the court of Louis VI and Louis VII of France, where Suger served as the friend and counselor. He was one of the earliest patrons of Gothic architecture and was convinced that all colors have a divine nature, blue in particular. It was approximately in the same period that the Virgin Mary’s clothes started to be painted blue, as a sign of grief for Jesus. Through the growing cult of the Virgin in the Middle Ages, blue became a popular color. One of the earliest examples is the famous Wilton Diptych.

In 2019, scientific evidence of the use of lapis lazuli in the creation of illuminated manuscripts was revealed. The pigment was identified in the form of powder consistent in size and composition with lapis lazuli–derived ultramarine pigment, which was found embedded within the dental calculus of a middle-aged woman buried in association with a 9th to 14th-century church-monastery complex at Dalheim, Germany. Their analysis suggests that the woman was likely to be a painter of richly illuminated religious texts. This woman represents the earliest direct evidence of ultramarine pigment usage by a religious woman in Germany.

Ultramarine pigment was mixed with a binder, usually egg yolk, and applied to the fresco “al secco” after the plaster had dried. This is how Giotto painted the magnificent Scrovegni Chapel in Padua in 1305.

Lapis lazuli’s diffusion in Europe began during the Crusades, but its rarity and cost meant that it could be afforded for the creation of artworks only by the richest of patrons. Grounded lapis lazuli was increasingly used by painters during the 13th and 14th centuries to make ultramarine and Cennino Cennini (c. 1360–before 1427) gives instructions on how to prepare this pigment in his Book of Arts.

Sandro Botticelli’s composition of The Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Christ Child was inspired by the work of Filippo Lippi. It is one of the first paintings where the Christ Child was rarely shown asleep, as a reminder of Christ’s death. Virgin Mary’s blue cape is consistent with this, and the analysis showed it is painted in ultramarine.

Lapis lazuli was imported to Europe, entering through Venice, therefore it was here where we first see ultramarine used. Earlier, azurite was being used for blue underpainting in Venetian painting. Azurite was considerably cheaper than ultramarine. Even Titian applied ultramarine frugally, only for most important elements in the composition. However, in the case of Bacchus and Ariadne the painting was packed with precious ultramarine of the highest level. This was possible thanks to the donor of the painting, that is the Duke of Ferrara.

Natural lapis lazuli is the most predominant blue pigment in this piece. It is mixed with lead white in the sky, the highlights, mid-tones of blue draperies, the distant landscape, and some of the flowers. In the blue cloak of Ariadne, specifically the shadows, and in the drapery of the Bacchante, ultramarine is used without lead white. Ultramarine is also mixed with lead white and a red lake for the drapery of the Bacchante with the tambourine.

In Northern Europe, we have great paintings done by great artists all displaying the beauty of lapis pigment in all its glory. The Annunciation by Jan van Eyck, Adoration of the Magi by Dürer, Death of Virgin by Hugo van der Goes, and works of Hans Holbein are just a few examples.

Raphael painted this altarpiece piece for the Ansidei family chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas in the Servite Church of S. Fiorenzo in Perugia and splurged on it. The final layer of Madonna’s blue drapery is painted as a glaze of the very expensive pigment, natural ultramarine.

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin of the Rocks is a perfect example of the stunning effect ultramarine can have on the overall artwork. Da Vinci’s piece serves as an excellent example of how ultramarine responds to oil paint. Since ultramarine was applied as an extremely thin glaze, it cracked in several areas during its drying process. This occurs because lapis lazuli interacts with the protein-like bands of the oil binder in a way that causes it to degrade.

Some sources mention that Michelangelo ordered huge quantities of lapis lazuli for the 1536–1541 Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel. According to Giorgio Vasari, Michelangelo planned to work over the ceiling with ultramarine (lapis lazuli) and gold, but never got around to re-erecting the scaffold. I have not found a scientific study to confirm or deny these theories.

Peter Paul Rubens started working on The Annunciation after his stay in Italy, where he had come under the influence of the great painters of the Renaissance. This Italian influence is evident from the unusually bright colors and the freestyle, which both contribute to the scene’s dynamics. Rubens used ultramarine for Mary’s cloak, a precious pigment made from finely ground lapis lazuli.

It was not until the second half of the 16th century that large objects carved from lapis began to appear in Italy. Prominent patrons are the Medicis who, during the 16th century, built up a unique collection of objects — from bowls, goblets, and jugs made from and adorned with this precious stone. Many of these objects, as the ewer in the image below, were carved in the workshop of the Miseroni brothers, Gasparo and Girolamo, from Milan.

Later in the early 1570s, Francesco I brought craftsmen from Milan to carve lapis in Florence. They were extremely skilled at fully exploiting the natural patterns of Lapis to represent seas and skies with clouds and at producing landscape tabletops.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, we observe more frequent use of ultramarine. The most famous example of the period is for sure Dutch master Johannes Vermeer who made extensive use of ultramarine in his paintings. So much so that it is said it ruined him financially. Vermeer was in love with the qualities of the paint, especially with the way it reflected light. Vermeer used genuine ultramarine in every painting, not only in the deep-colored objects, but also in portions of white drapery, ceramic jugs, black marble tiles, green foliage, white-washed walls, and even in the shadows of the brilliant orange gown in The Wine Glass.

“Ultramarine is used in relatively small discrete regions of the distinctive true blue color for which this expensive pigment is renowned; such as for the upholstery of the chairs in Young Woman standing at a Virginal and the panel of curtain behind the virginal. Touches of a bright mid-blue of ultramarine combined with lead white are introduced in the landscape pictures and for the jacket of Young Woman standing at a Virginal, and for the cool blue-greys of the tiled floors. Ultramarine has also been identified in the cool highlight on the upper edges of the young woman’s outstretched arms in the Young Woman seated at a Virginal. More unusually, ultramarine has been combined with green earth to form a range of blue-greens and greeny-blues. In Young Woman seated at a Virginal the largest area of blue in the painting is her dress, but here ultramarine has been combined with green earth to produce a distinctive blue-green color.”

Helen Howard, Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure exhibition materials, National Gallery.

The Oxford Union Murals is a series of paintings depicting scenes from Arthurian myth. A team of Pre-Raphaelite artists including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Morris, and Edward Burne-Jones executed it. They used ultramarine; its price was still high and not accessible for everyone in the middle of the 19th century.

For this reason, in 1824, Société d’encouragement pour l’industrie nationale offered a 6,000 francs reward to whoever will invent a synthetic ultramarine at an affordable cost. After four years, the prize was awarded to Jean-Baptiste Guimet, a French chemist. However, because all the pigment particles were very even and reflected light in the same way, the resulting image had a unidimensional look– lacking the depth, variety, and visual magnetism of original ultramarine.

In May 1960, Yves Klein developed and patented International Klein Blue (IKB). It was made of a synthetic resin binder which suspends the color and allows the pigment to maintain as much of its original qualities and intensity of color as possible. Ultramarine is the pigment made from natural lapis lazuli, while IKB, its synthetic equivalent, is sometimes called “French ultramarine.”

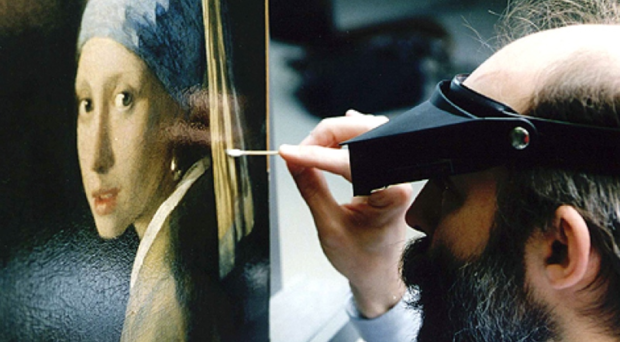

Ever since, natural ultramarine has rarely been used for painting, and more for restoration works, such as the one for Vermeer’s The Girl with a Pearl Earring.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!