Who Was Laura Knight?

Laura Knight (1877–1970) followed a rare path for a woman at the turn of the 20th century. She was admitted into the Nottingham School of Art at only 13 years old and went on to become an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1927. She was the first woman to be elected as a Royal Academician since the 18th century, the first to be given a retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy, and in 1932 she was elected president of the Society of Women Artists.

Alongside the likes of Samuel John Lamorna Birch and Alfred Munnings, Knight was known by name throughout Britain. And yet, throughout her 70-year career, Knight chose not to paint the grandiose, but rather the beauty that is all around us, right under our noses. She eventually forged her own distinctive style, painting slices of life with a focus on modern women.

Here we explore five such paintings.

1. Self-Portrait with Nude

In Self-Portrait with Nude, Knight is featured painting the nude body of fellow artist and friend Ella Naper (1886–1972). This career-defining work demonstrates Knight’s mastery of human anatomy despite having been barred from studying the nude from life at Nottingham art school. Refusing to be limited by the restrictions placed on women at the time, Knight hired her own private model to come to her home. Many sharp-tongued critics came out against the painting, the Telegraph even calling the work “something dangerously close to vulgar.”1 It is now considered one of her great masterpieces and a seminal study of the female gaze.

2. The Cornish Coast

Recurring throughout Knight’s body of works are coastal and clifftop images of confident women subjects contemplating nature around them. Many are set in Cornwall, where the artist settled in 1908 and where she enjoyed a “carefree life of sunlit pleasure where she affirmed her love of painting out of doors in order to achieve maximum veracity.2 Bucolic scenes of female freedom like this one pervade her early oeuvre.

Painted in situ, these scenes are evocative of the long Edwardian summer, a period of especially high temperatures in Great Britain between 1910 and 1914. Young women in modern dress wander the outdoors in what might be described as the antithesis of hortus conclusus paintings. No longer enclosed in the home, these women exude independence. They are free to roam the great outdoors as the female counterparts of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer. Raised by her mother, having been abandoned by her father as a young girl, it comes as no surprise that the majority of her scenes are devoid of any male presence. What’s more, by 1917 in England most men were away fighting in the World War I.

3. The Ballet Girl and the Dressmaker

While living in London, Knight spent evenings watching the Ballets Russes, which provided “complete satisfaction for every aesthetic sense.”3 Instead of capturing the dancers in action on stage, Knight preferred to paint them between acts, or as they rested. She even gained backstage access which allowed her to set up her easel in the cramped dressing rooms of prima ballerinas. In The Ballet Girl and the Dressmaker (1930), we encounter a dancer slumped over in her chair as her seamstress works hastily on alterations. The sense of immediacy engages us in the scene, while leaving us with more questions than answers.

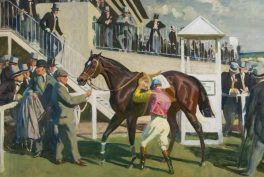

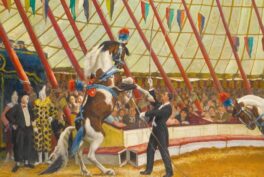

4. Circus Matinee

Being at the heart of the action was part and parcel of Knight’s approach to painting, which often brought her to frequent places deemed unacceptable for a woman at the time. Knight made numerous trips to study and paint the circus, where she was tasked with capturing fleeting moments. Drawing from the immediacy she had learned from her early plein-air painting in the countryside, she painted nudes, dancers, and circus entertainers.

Knight joined the Mills’ Circus, going on tour with them for four months—even learning acrobatics herself—and shared temporary lodging with clowns and acrobats. Her Circus Matinee from 1938 depicts a behind-the-scenes moment of circus entertainers between performances. This illuminated mélange of spotted haircoats and striped suits showcases Knight’s talent for capturing a diverse range of colors and subjects.

5. Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-Ring

One of the genres for which Knight is most famous is her iconic wartime propaganda. At the outbreak of World War II, the painter enlisted with the War Artists Advisory Committee. As an official war artist, Knight seized the opportunity to produce a pictorial record of the effects of war, commissioned by Sir Kenneth Clark in 1939. She used this appointment not only to record the wartime experience, but to showcase the vital role of women in the war effort and to encourage others to participate. She painted action-filled snapshots of women diligently working in factories, engaged in tasks for the Auxiliary Air Service, and hoisting barrage balloons.

Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring (1943) is the product of Knight having spent the day in an armaments factory closely observing a Welsh munitions worker on the job. Knight’s wartime documentation, however, was not limited to women. In 1946, she traveled to Nuremburg where she was commissioned to create sketches of the Nuremburg Trials as a war correspondent.

I Paint Today

19th-century French caricaturist Honoré Daumier famously advised: “One must be of one’s time and paint what one sees.” Decades later, acclaimed British painter Laura Knight seems to have taken up his call. She painted children, marginalized people, landscapes, ballerinas, flamenco dancers, wartime workers, acrobats, and circus animals—demonstrating not only the breadth of her talent but her insatiable curiosity for the quotidian. And yet, Knight never fully enjoyed her own creative freedom, writing in 1965 that “Even today, a female artist is considered more or less a freak.”4

Throughout her lifetime, Knight was a constant advocate for female artists and fought for greater recognition for women in the arts. Today, the exquisite paintings she created throughout her career endure as gifts for anyone willing to receive them. They can be visited in public collections in the UK, including the Imperial War Museum, the Leicester Museum & Art Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery, the Manchester Art Gallery, and the Tate.