5 Guises of Maurice Denis

Maurice Denis was a French Symbolist painter, known as a prominent member of the Nabis. His work was influenced by the art of the Renaissance,...

Valeria Kumekina 25 November 2024

A literary fan of Edgar Allan Poe with a Symbolist approach to painting, Léon Spilliaert thrives in the disenchantment, emotion, and decadence that characterize his works. Let’s take the time to break down the motifs of waiting women, a reflection of self, ghostly characters, and oozing landscapes in his oeuvre.

When the rest of the city was sleeping, Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946) would walk along the moonlit streets of Ostend; located on the Belgian coastline, the city heaved with tourists in the summer and became quiet as the season changed. Favoring the melancholy, empty streets, Spilliaert calmed his chronic insomnia and was often inspired by late-night walks.

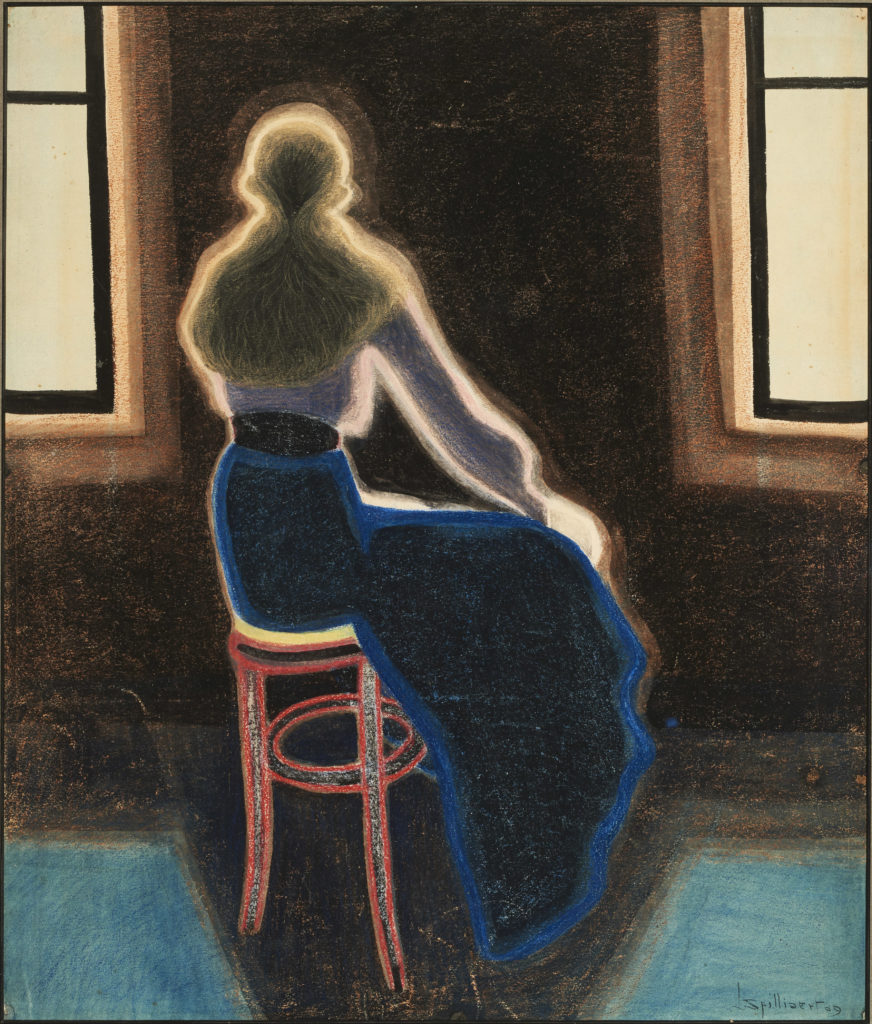

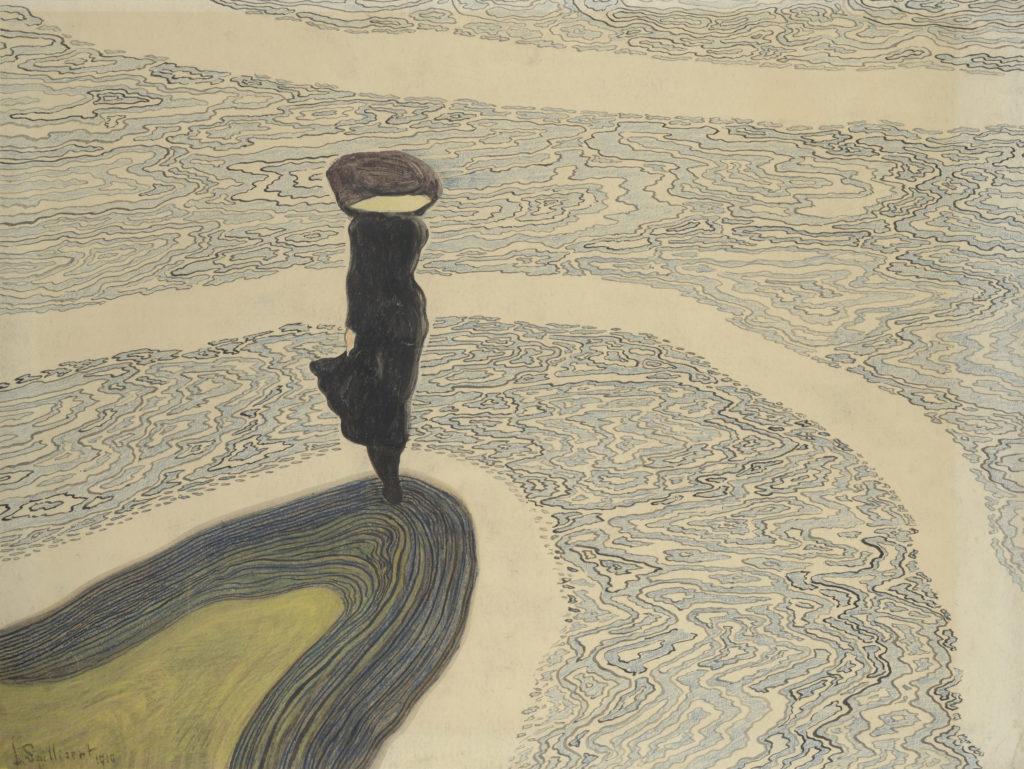

Figures, particularly women, are often depicted as waiting in Spilliaert’s work. In a recurring motif throughout the show, a solitary subject is turned away from the viewer and appears to gaze out at the shoreline or through a window; this sense of longing may have stemmed from Spilliart’s own physical ailments, as he suffered from chronic stomach pain since a young age which led to various complications in his life. For example, at the age of 18, Spilliaert enrolled in Bruges’ Royal Academy of Fine Art but shortly had to withdraw from the course due to his health issues. Subsequently, he did not return to formal art education and taught himself.

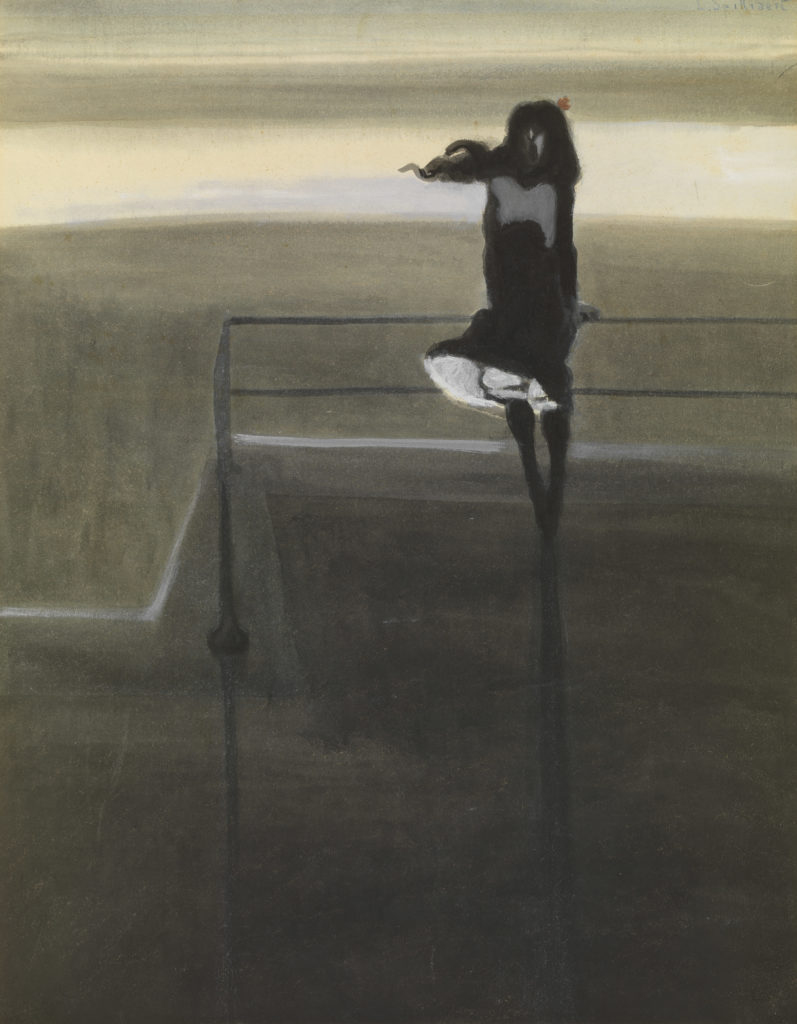

In his work, Spilliaert’s lonely figures reflect his own isolation – the fisherman’s wives that wait on the promenade, or the wide-eyed woman with her back against the railings. With various images tinged with a longing for something that is not yet present, there is an ongoing sense of life happening elsewhere. The sadness is prevalent, as Spilliaert uses his internal landscape as a reference for various seascapes and portraits. In his own words, Spilliaert wrote:

I’m tired of waiting for luck to come my way, in the end that leads to abjection.

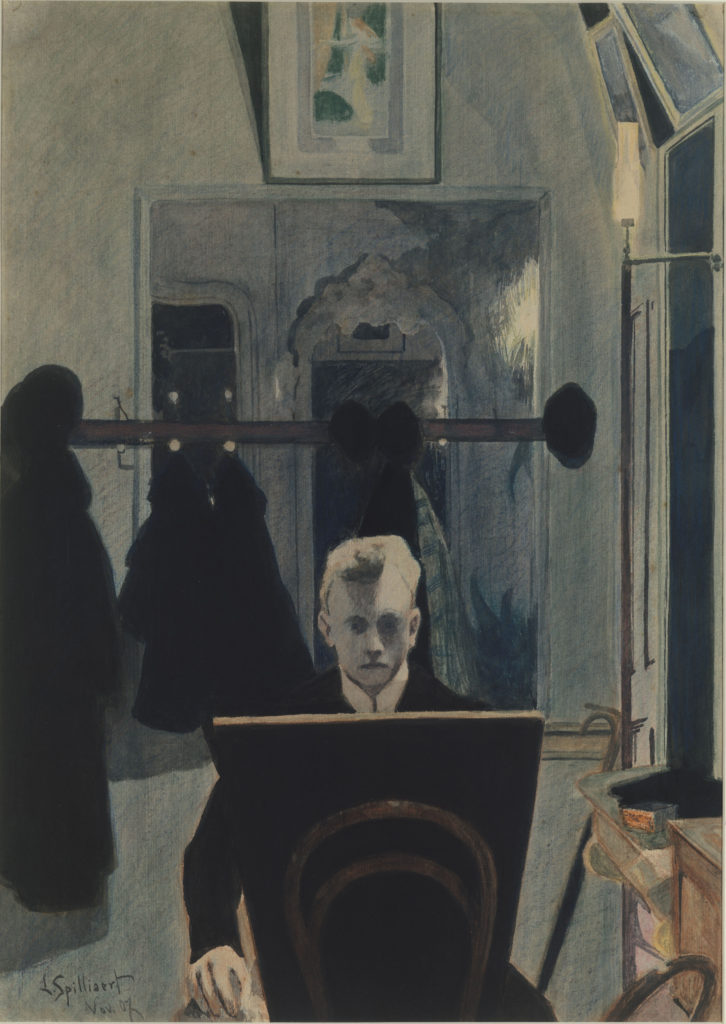

The chronic stomach pain was also a cause of Spilliaert’s insomnia; both a blessing and a curse, some of his best self-portraits were created during these sleepless nights. Spilliaert made the sun-room his studio, using one of the many mirrors there as an aid, as the sun-roof invited beams of moonlight and distorted shadows as atmospheric elements to his self-portraits; these works were often haunting and macabre, with a ghostly pallor to his face and dark rings under his eyes. Baring all to the viewer, Spilliaert was unapologetic in his depictions of self and they are now the most popular aspect of his artistic legacy.

Over a two-year period in his early twenties, he produced many self-portraits at different levels of distortion or obscurity. Much as with his depictions of waiting women, his self-portraits also serve as an introspective gateway to his desire to achieve more, internal suffering, and prevalent solitude. Incorporating various empty frames and often evoking an uncanny feeling, Spilliaert’s self-portraits linger like a dream bordering on a nightmare.

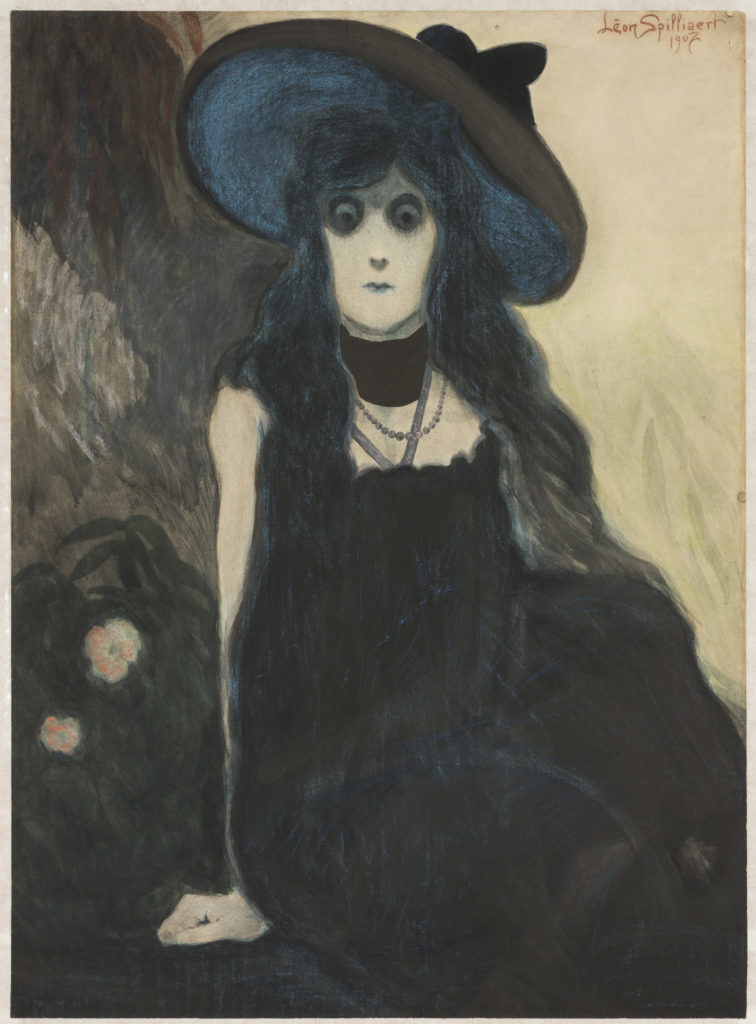

Spilliaert didn’t only depict himself in a haunting, ghoulish manner. In works reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, Spilliaert uses flat colors with his signature contrast between light and dark to depict disturbed characters. For example, The Absinthe Drinker sees a wide-eyed woman’s inner turmoil, despite her fashionable dress and accessories; through an image riddled with anxiety, Spilliaert depicts the darkness of addiction in a particularly emphasized style.

Meanwhile, a similar anxiety tint works in A Gust of Wind, as a dark, lonesome figure stands with a gaping mouth and her hair blowing in the breeze. The viewer is invited to ask what happened to these characters, and what caused the alarm on their faces; much as with Spilliaert’s self-portraits, there is an air of mystery that enshrouds the troubling figures. Both women, along with many of his other characters, appear on the edge in one way or another; physically on the edge of the coastline, or walking the line between bourgeois society and emotional disturbance, these figures always seem seconds away from transgression. Restrained by a metal railing or perhaps important company, Spilliaert’s characters cannot hide their true state on their faces. Straddling the space between acceptance and rejection, the liminal figures embody the artist’s youthful alienation.

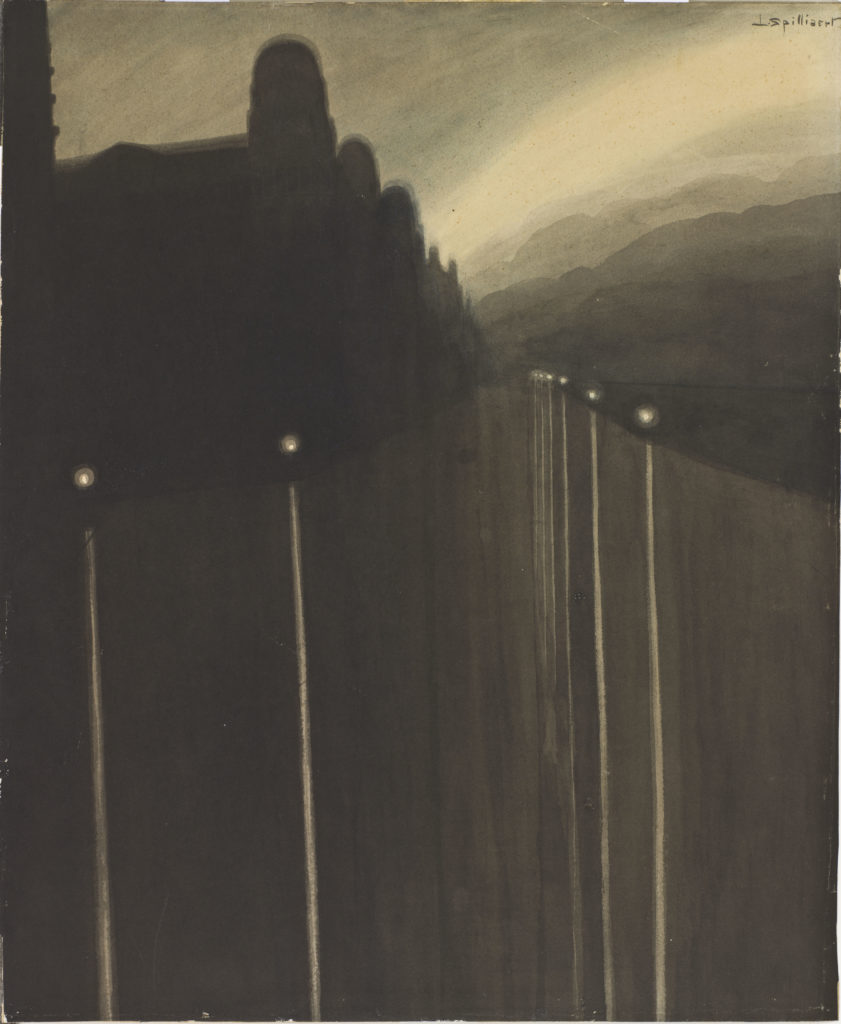

Despite the ongoing industrial revolution that was well underway in Belgium, Spilliaert often depicted empty streets, forests, and landscapes. Atmospheric through his monochrome pallet, the streaming use of light, and contrasting shadows of looming trees or buildings, Spilliaert embraces the hours when sunlight declines and life seems to be on pause. Sometimes tranquil, others haunting, the artist uses streetlights and the soft glow of the moon in many of his works.

Experimenting with perspective, Spilliaert obscured his hometown and used it as an ongoing source of inspiration. In the year that Dike at night. Reflected lights were painted, Spilliaert had moved into an attic studio that overlooked the port. Witness to the changing tides and skies, these sights often fed into his paintings as he cherished the closeness to such natural shifts. Whilst in later years – after the marriage to Rachel Vergison, the birth of their child, and a partial move to Brussels, Spilliaert’s natural landscapes softened, his younger depictions of Ostend are characteristically brooding with existential questions. Relishing in what is void, Spilliaert’s early depictions of the natural world are quietly as impactful as his paintings of people, drawing us into the empty streets as much as into the eyes of his longing characters.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!