Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

13 October 2024 min Read

Whether you are within an academic environment or at a coffee shop, when the term “Neoclassicism” and its huge influence on the visual arts arise, you are likely to hear the name Jacques-Louis David many times. David was not only the painter who developed an epochal artistic manner in the Neoclassical style but was also one of the greatest painters of his century. One of his masterpieces, Leonidas at Thermopylae, a painting of vast dimensions, namely 395 x 531 cm (12.9 x 17.4 ft), took 15 years (1799 to 1814) for him to complete.

Let’s observe the painting and learn what makes it so remarkable!

Despite his affluent family and unmatched aptitude for painting, David’s life was rather turbulent and eventful. He was born in Paris on August 30, 1748. When he was little, his father was killed in a duel. His mother was also absent during his youth. Hence, his uncles who were wealthy architects raised and supported him. Even though he was not particularly successful in his academic life, he never lost his passion for art. This rapidly became the mainstay force that provided him with recognition and success. From Maximilien de Robespierre to Napoleon Bonaparte, he mixed with various prominent historical figures throughout his lifetime. As a result. fame and praise were things he was accustomed to – as well as arrests, exiles, and setbacks.

Many artists had an influence on David’s works, among them Joseph-Marie Vien, Anton Raphael Mengs, Nicolas Poussin, and Caravaggio. However, David did not strictly employ any of their artistic styles. Instead, he harmonized their perspectives and formed his own distinctive manner. In fact, he did this so well that, today, we have an aesthetic division in visual arts named Davidian Neoclassicism. He produced canonical paintings such as The Death of Socrates (1787), Anger of Achilles (1825), The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799), and many others. His paintings are engraved in all our minds, but in this article, we will look at his painting, Léonidas aux Thermopyles. Since this is a kind of painting that contains an immense amount of historical details, I ought to narrate the historical background so that we can truly enjoy and understand the work.

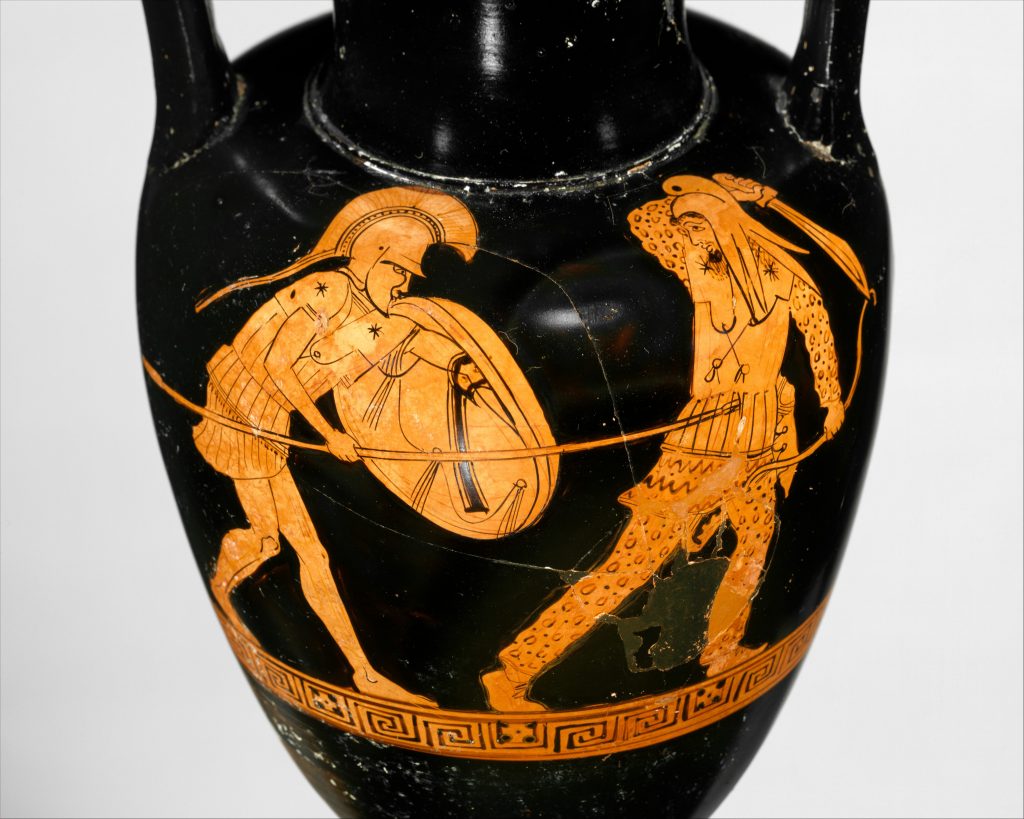

In the middle of the 6th century BCE, the Achaemenid Empire, led by Cyrus the Great expanded its territories immensely, especially towards the northwest of their native region. After they defeated the Lydians in circa 547 BCE, they rapidly established their presence in Asia Minor. Their existence there remained mostly intact until the conquest of Alexander the Great. As a result, the Persians who had settled all over the region, became the sole authoritative power over the inhabitants of the Asia Minor such as the Ionian Greeks. But the strained relationship between them reached its peak and erupted in 499 BCE. This was when the Ionian Greeks revolted against their satrapy, or provincial governor, with the support of city-states Athens and Eretria. Nevertheless, the Persians were able to stabilize this riot quickly. However, they were not content with simply suppressing the Ionian Greeks.

Instead, they began to make preparations for their first large-scale campaign against mainland Greece, primarily aiming to subjugate Athens and Eretria. However, the military objectives of King Darius I failed when, against all the odds, the numerically inferior Athenian army was victorious at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. Despite this, the Persians did not give up easily. Ten years later, we arrive at the place where David derived his inspiration – 480 BCE, the Battle of Thermopylae. This time the Persian army launched a much more advanced and organized campaign against the Greek city-states under the leadership of King Xerxes I. Under his trusted commander Mardonius, the Persians utilized both their land and naval forces. Even though the Greek forces led by Leonidas I failed to stop the Persians from reaching Athens, they exhibited a legendary example of courage and tactical ingenuity.

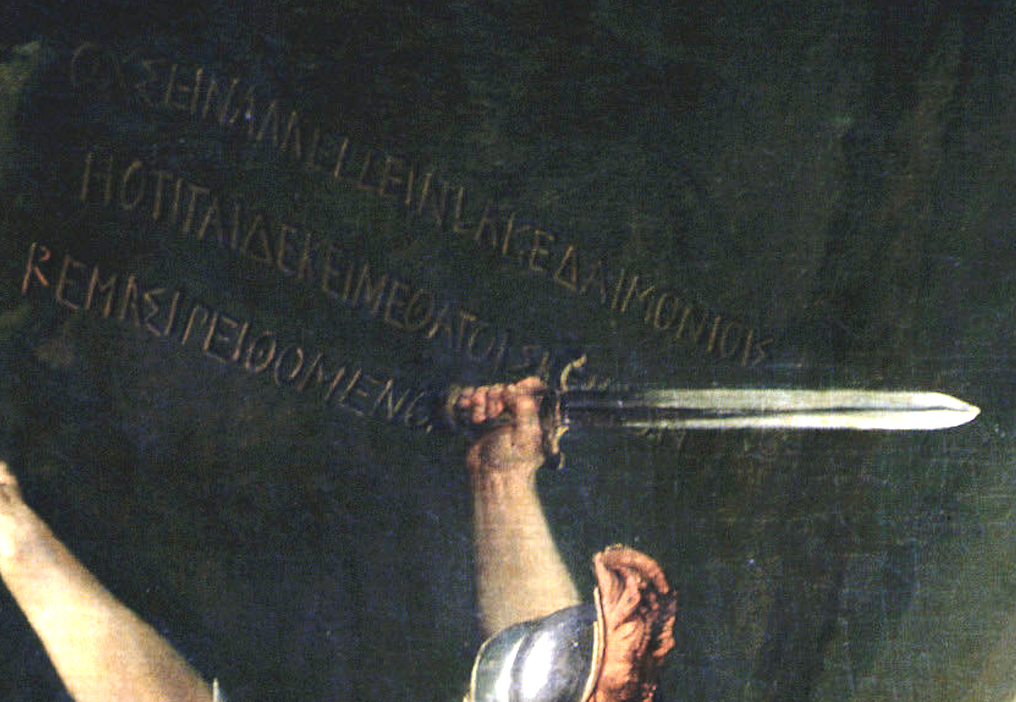

Just like almost all of David’s works, the composition is exquisitely rich. A distinct meaning flourishes in every inch of this painting. Let us start with soldier in the top left corner. He is inscribing the famous epitaph of Simonides on the mountain with the pommel of his sword. It reads:

Ὦ ξεῖν’, ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε

κείμεθα, τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι.

Go tell the Spartans, thou who passest by,

that here, obedient to their laws, we lie.Epitaph of Simonides of Ceos

David’s choice of incorporating this epitaph into the composition adds a unique literary aspect to the work. The mentality of “victory or death” was always an essential part of Spartan warfare and society. However, by including it within the work, David put even more emphasis on the Spartan’s determination and the sentimental aspects of the battle.

Continuing, we find another inscription on an altar, right behind the warrior who is tying his sandal. On the front side of the altar, it reads “HERAKLEOS”. There is also bread, a knife, a cup and a jug on it. It is evident there has been a sacrifice to Heracles, the son of Zeus. In the primary literary sources such as the Histories by Herodotus, it is stated and believed that King Leonidas had direct ancestral ties with Heracles. On the other hand, in his third book of Descriptions of Greece, Pausanias, who lived centuries after the battle, stated that the Spartans had often made sacrifices to Heracles at times of cultural and religious importance. Therefore, David brilliantly highlights these two historical accounts and provides a genealogical and cultural context within the work itself.

Our last inscription is located on a scroll near the right foot of Leonidas. On it, it reads “Leonidas, son of Anaxandrides, King to the Gerousia. Greetings.” The Gerousia was the council of elders who had judiciary and political power within the city-state of Sparta. With this scroll, David ratifies the authority of Leonidas.

When one carefully observes the composition as a whole, the first thing that will be recognized is that there is a general sense of haste and urgency among the warriors. This is because they are getting ready for what is coming – the Persian army. Behind our subjects, there are thousands of Persians, their ships in the bay, and now marching towards the Spartans.

At the top right corner, there are two trumpeters who are signaling that the enemy is near. It is time to take up their positions within the phalanx formation.

Right under them, we see two warriors who are quickly trying to gather their military equipment from a tree. On the tree, there is a lyre and laurel wreath. These are significant objects that symbolize the oracular god Apollo. In addition, one might argue that David intended to point out that the Spartans had a divine support.

Near the two trumpeters, there are two Greek villagers who are escaping from the battlefield with their goods. They might symbolize the citizens who evacuated their cities because of the Persian invasion.

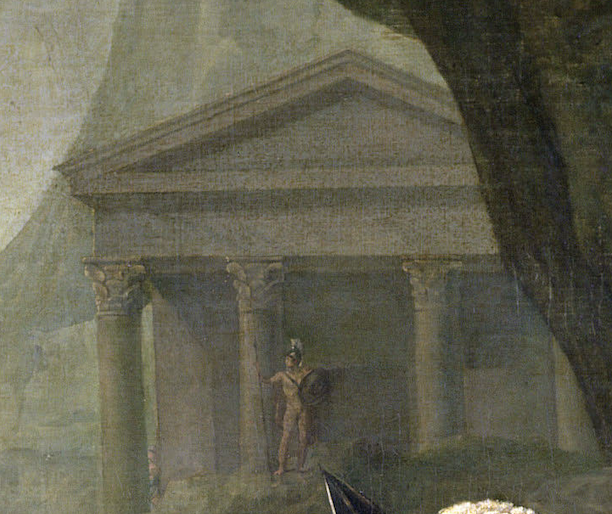

Right above Leonidas, there is a structure. In front of this structure, we see a Greek warrior. At first glance, the building seems like an ordinary Greek temple but it holds more meaning than that. It symbolizes the accomplishments and values of the Greeks. The warrior who stands in front of him demonstrates that the Greeks are ready to fight and die for their civilization. It shows that they are willing to do everything to preserve what’s theirs.

Right under the soldier who is inscribing the epitaph of Simonides on the mountain, there is a warrior whose eyes are shut. His name is Eurytus. According to Herodotus, Eurytus and Aristodamus were close friends. Before the main battle, their eyes were infected badly and this infection heavily diminished their sight. As a result of this, King Leonidas told them that they were free to go home since they would not be able to contribute to the battle in any meaningful way.

However, Eurytus chose to stay and fight regardless. The man behind him, wearing a blue bandana, is a helot who is assisting Eurytus towards the battlefield. On the other hand, Aristodamus chose to go back to Sparta. Naturally, he was despised and hated by the Spartans for his cowardice. Yet, he was able to redeem himself in the Battle of Plataea one year after the Battle of Thermopylae.

On the left side of Leonidas, there are two Spartans. There is a noticeable age difference between them. The young one is saying something to the older man’s ear. One of the highly plausible interpretations of this is that they are father and son. The son is bidding his last farewell to his father since they both know they will fall during the battle.

And at last, Leonidas the king of Sparta. The first thing that we notice is his stoic state. Unlike the other warriors in the painting, Leonidas is calm and aware of what is coming. At the same time, he is ready. His right foot is on the ground and his sword is not in the scabbard. In his left hand, he is holding his mighty shield and spear. He is placed in the most vital point of the composition, in the middle of every crucial figure and symbol. With his lighting technique, David visually affirms that Leonidas is the main subject of the painting. The light increases towards him and reaches its peak on his body.

Leonidas at Thermopylae is not only a splendid piece of art but it is also a brief ancient history lesson. It is significant to note that what we look at is much more than a portrayal of a moment in the vast timeline of history. It is an account or story that narrates the entire silhouette of a period.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!