Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Luchita Hurtado (1920–2020) was an artist, photographer, poet, environmentalist, activist, feminist, fashion designer, and so much more over the course of a lifetime that spanned a century.

Luchita Hurtado was born in Venezuela. She migrated to New York City at the age of eight, married for the first of three times when she was 18 and moved around in her twenties. She settled in Santa Monica with her third husband and was the mother of four sons. Hurtado’s lifelong art practice did not receive critical and international acclaim until later in her life.

In 2019, Hans Ulrich Obrist organized a career retrospective at the Serpentine Galleries in London that traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in early 2020. At the age of 99, and just months before she passed, Hurtado was fortunate to have participated in this celebration of her long and prodigious life as an artist.

Luchita Hurtado’s life, until recently, was defined by her romantic relationships and a multitude of friendships and acquaintances with many prominent artists and thinkers from the 20th century. She always identified herself as an artist and moved within artist circles, but aside from participating in the occasional exhibition, she did not actively pursue a professional career as an artist.

Considering Hurtado’s staggering body of work, it is frightening to think that she almost slipped through the cracks of art history. Although her art was no secret, it was not until 2015 that Ryan Good, the former studio manager of her late husband (Lee Mullican, who died in 1998), discovered a sizable inventory of paintings and works on paper. Upon learning that these works were by Hurtado, Good set in motion a chain of events that culminated in the 2019 retrospective at the Serpentine Galleries.

In the following excerpt from a 1995 interview, Hurtado helps one understand why we only just discovered the full breadth of her work.

Well… life has a way of holding up your work, too… I’ve never been able to pursue a career properly. I’m always involved in life too much. And so, I write poetry, I paint, I do all these things, but I’m not running in any way after a dealer, to show or to publish or to do any of these things.

Luchita Hurtado in conversation with Paul Kalstrom, Archives of American Art, April 1995. Smithsonian Institute.

Furthermore, addressing the historical tendency for male artists to be recognized and female artists to be overlooked with regard to artist couples, Hurtado said the following:

There again, I mean it’s a matter of couples. If I am sure that if this was that important to me to be a great success, to be number one, I would have achieved it. I would have, but it wasn’t, so I didn’t. So life, I think, was number one.

Luchita Hurtado in conversation with Paul Kalstrom, Archives of American Art, April 1995. Smithsonian Institute.

Even though Hurtado prioritized her life, a good portion of which voluntarily revolved around her husbands and children, she also found a way to channel her passions into an art practice that lasted 80 years. This brings us to a recurrent anecdote shared by the artist in statements and interviews over the years:

My grandmother, Rosario, taught me how to sew. If she caught sight of me sitting under a tree enjoying the afternoon breeze, she would ask me to bring her my favorite dress. ‘Idle hands tempt the devil, she would say; then together we would undo the hem. Once done, she would say, ‘Now, sew it up again and let me see how well you can do it.’ It never occurred to me to ask her why it was that when I daydreamed I was tempting the devil, whereas when boys daydreamed they were lost in thought, planning some great project.

Luchita Hurtado, in: Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts & Politics (Vol. 1, No. 4, Winter 1977-1978, Women’s Traditional Arts, Politics of Aesthetics, page 83).

This reminiscence appeared in a 1970s issue of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts & Politics when women artists were voicing their frustrations towards gender biases and traditions that hindered the individual and collective development of women. This event from Hurtado’s childhood that occurred early in the 20th century is demonstrative of the artist’s mental fortitude and her ability to disregard convention.

Hurtado gave herself permission to think and allowed her mind the freedom to explore. The artist’s intellect was unleashed from an early age when she attended Washington Irving High School in New York City and secretly studied art (against her mother’s wishes for her daughter to go to school to be a seamstress). Her lifelong art practice is marked by ongoing thoughtful contemplation with regard to her own being and one’s relationship to the earth, air, fire, and water.

At the age of 18, Hurtado married Daniel del Solar who was a fairly established journalist. She had two sons with him, Daniel and Pablo. They lived briefly in the Dominican Republic at the invitation of the dictator General Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina. However, their marriage ended abruptly and shortly after the birth of their second son. During the years with del Solar in New York, Hurtado became close friends with Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi and Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo. The latter was a frequent house guest who used their kitchen as a makeshift studio space when he was in Manhattan.

After the end of her first marriage, Hurtado supported her sons by painting murals for the windows of the Lord & Taylor department store and as an illustrator for publications owned by Condé Naste. She remained friends with Noguchi who invited her to join him on a visit to the hospital room of Frida Kahlo who was in New York to undergo a spinal fusion. Hurtado and Noguchi were joined at Kahlo’s bedside by a number of other Surrealists who had fled to New York from Europe during World War II.

Noguchi also introduced Hurtado to her second husband, Austrian-Mexican Surrealist artist Wolfgang Paalen, at the opening of his solo show at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in 1945. This meeting led to Hurtado’s second marriage. The couple later moved to Mexico where they traveled around the country looking for Pre-Columbian art. Their shared interest in these objects took them to San Lorenzo, Mexico. Here, at the request of Paalen, Hurtado photographed the ancient Olmec heads located at this site. These photographs were later published in the December 1952 French publication Cahiers d’Art.

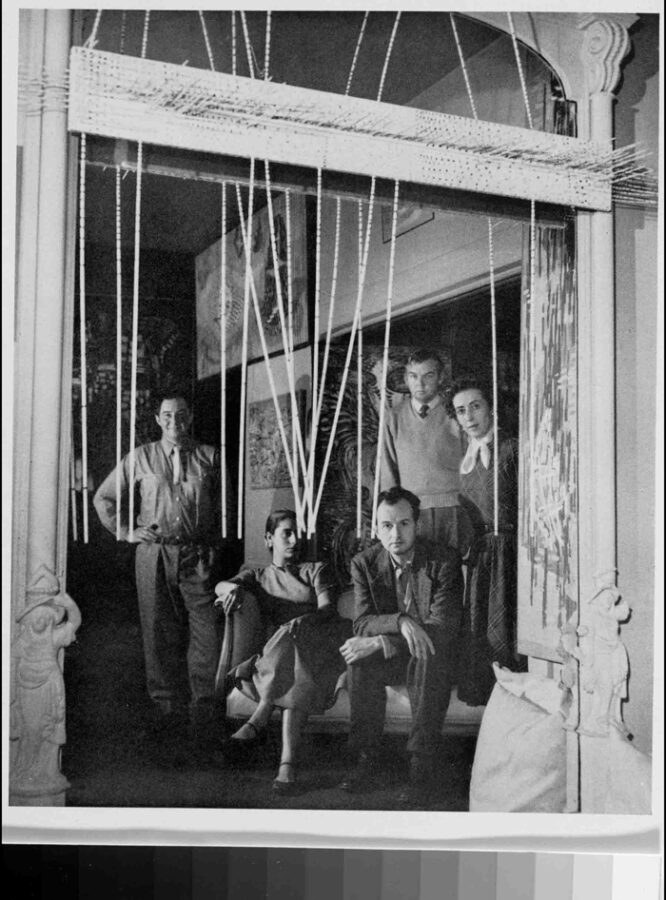

While in Mexico and during her marriage to Paalen, Hurtado was in close acquaintance with Surrealists André Breton, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, Roberto Matta Echaurren, and other established artists, archeologists, and thinkers. Sadly, her time in Mexico concluded with the tragic death of her five-year-old son Pablo who succumbed to polio. This loss led Hurtado, Paalen, and her son Daniel to relocate to Mill Valley, California in 1948. After this move, along with the young artist Lee Mullican (originally from Oklahoma) and British artist Gordon Onslow Ford, Paalen started the Dynaton group, an offshoot of Surrealism. This artistic collaboration was brief and by 1951, Hurtado’s marriage to Paalen had also come to an end.

Hurtado moved to Santa Monica with her son Daniel del Solar from her first marriage. At that time, she was pregnant with her first of two sons with Lee Mullican. She would eventually marry Mullican in the mid-1950s and remain married to him until his death in 1998. Mullican was a prolific artist and a professor at UCLA. Although he was not widely known, he was held in high regard by those more familiar with the local art scene. Their older son, Matt Mullican, is a renowned performance and installation artist. Meanwhile, their younger son, John Mullican, is a writer and filmmaker whose work includes a documentary film about his father, Finding Lee Mullican (2008).

Hurtado and Mullican kept a base in Santa Monica, but from the mid-1970s onward they divided their time between California and Taos, New Mexico.

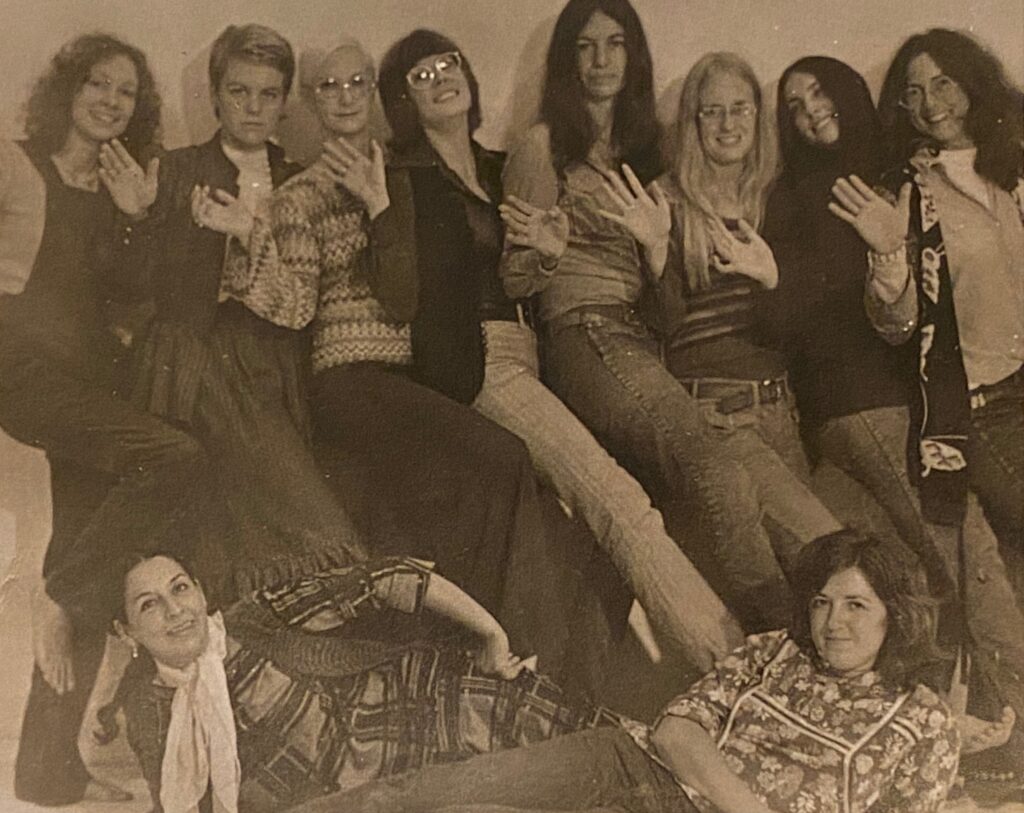

When she was in her fifties, Hurtado participated in the feminist art movement and the corresponding events that were taking place in Southern California. Womanhouse (1973), the exhibition organized by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro (the artists and co-founders of the Feminist Art Program at Cal Arts), is just one of the historical milestones of this movement. This exhibition was followed by the opening of the Woman’s Building where Hurtado had her first solo show (1974).

During this period, Hurtado attended meetings of the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists. From this larger collective of women who attended the first meeting organized by artist Joyce Kozloff, Hurtado broke off into a smaller group of artists that included Vija Clemins, Alexis Smith, Avilda Moses, Mako Idemitsu (video and film artist), Johanna Demetrakas (filmmaker, Womanhouse 1974), Barbara Haskell (curator at the Whitney Museum of Art), and Susan Titelman; a group of artists that she continued to meet with on a regular basis and remained in touch with over several decades.

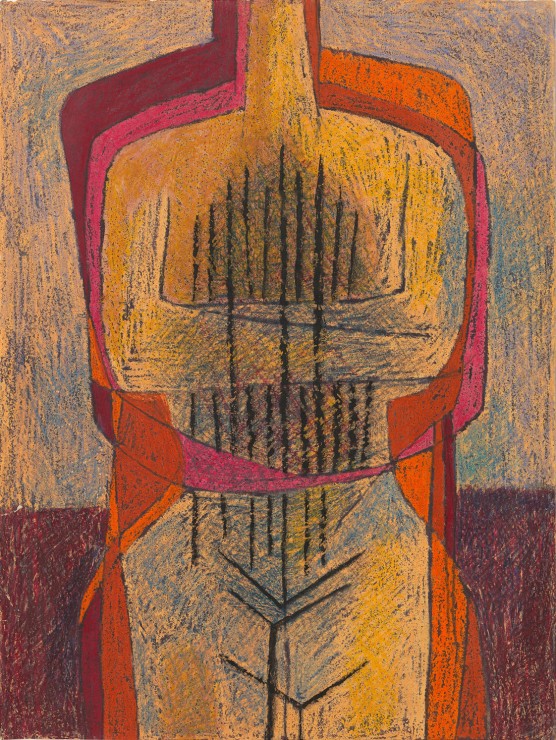

One of the central themes running through Hurtado’s extensive body of work is the relationship between the self/body to the four elements: earth, fire, water, and air. A number of paintings dating back to the 1970s and midway through the artist’s life, show various developments of this theme generated through the female form, geometric patterns, abstraction, and language. These works are but a fraction of the total art produced by Hurtado. There is no doubt that her output will keep current and future generations of art historians and curators busy.

In Hurtado’s paintings from the 1970s, the female form does not appear directly in front of the viewer but instead stands over or at the edge of the picture plane. These unusual positions adopted by the artist are initially deceiving because at first glance the bodily forms can be confused for other forms of nature. However, they are incredibly compelling for the control or restrictions they place on the viewer’s gaze. The nude surface of these headless bodies is not on display or purely decorative for the delight of the viewer. These are contemplative paintings, expressions of the interior, and the mental space beneath the surface.

In Untitled (1971), we are looking down at the artist’s nude body, seemingly from a shared perspective with the subject. In this case, the subject holds a lit match in one hand and a cigarette in the other. The body is viewed from above, no head is visible. As the form shifts into focus, it becomes clear that we are looking down and following the graceful descent of a female body. This is a moment of solitude and the dark swirl of colors that fill the space around the body responds to the flame from the match. In this charged, yet quiet painting, fire attracts the eye as it was a subject of fascination for the artist.

Her Moth Light paintings from the mid-1970s continue to play with the laws of attraction, but in this case through color and geometric forms. There is no sign of the human figure but a bright square or rectangle in the center of a canvas contrasted with color. The intent was that the center would bright enough to attract moths. This playful approach to attracting the eye and the attempt to paint light can be linked to the artist’s captivation with fire.

In other paintings from this period, the imaginative positions of the female figure along the periphery are paired with geometric patterns. These backgrounds recall patterns of Native American woven objects. Also in some paintings, bold images of fruit appear as well. Sometimes these paintings depict a reclining torso receding into space, an image that can be easily confused with the earth in a landscape painting. Furthermore, the choice to paint the body in earth tones encourages this visual connection to the land.

Untitled (1970) is mesmerizing for the female forms on either side of the painting that could be perceived as two women conversing—or duplication of the artist as subject— and standing on a brightly-patterned rug. The figures’ heads are not depicted but the V formation of the animated pattern between the figures might be representative of the intellectual, passionate, or emotional exchange occurring either between two figures or within one’s self.

These bodies without heads guide the viewer to look in, down, or across the canvas. The body is not an object to be looked at but rather the subject of these paintings is actively looking at itself with the viewer.

Sky Skin paintings, a term coined by the artist, are more conceptual but do not let go of the figure which takes form in the sky. These masterful constructions of the sky, feathers, and the body continue the artist’s imaginative and deceptive experimentation with figurative landscapes. Individual feathers are gracefully placed across a sky that is artfully cropped by surrounding rock formations resulting in figures whose skin is the sky. The body gravitates from the sky to land across this series that fuses the body with the earth. The two have become interwoven and poetically connected as articulated in one painting from this series bearing the title The Umbilical Cord of the Earth is the Moon (1977).

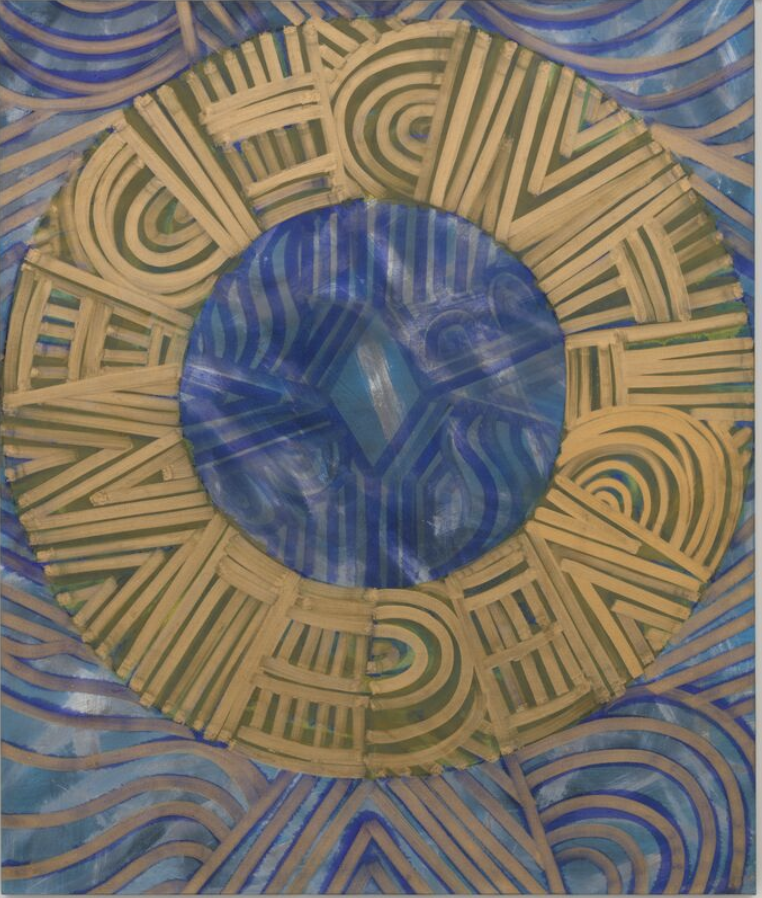

The artist articulated herself through language in the I am series of paintings. These pieces were originally featured in her solo exhibition at the Woman’s Building in 1974. The artist filled canvases with the words such as “I am” or “I live I die I will be reborn.” The canvas was then cut and sewn back together into either narrow strips, large panels, or circular forms that transformed the letters into patterns. The seams of the canvas that had been sewn together and re-stretched transformed the words into indecipherable patterns for paintings that were presented as self-portraits.

These sewn canvases integrate the artist’s seamstress skills into her painting practice. Even though Hurtado was reluctant to become a professional seamstress when she was a young woman, she relied on these skills when she was pregnant with her first son in 1940. She made maternity clothes out of necessity but continued to sew her own clothes because it was the most affordable option for dressing fashionably. Hurtado essentially had a love/hate relationship with sewing. It originated from her grandmother and mother’s insistence on sewing, defined by tradition as a female trade, to occupy her hands and serve as a source of income. The artist returned to this craft initially for utilitarian purposes to copy high fashion design for personal use but eventually brought it into these self-portraits composed of text and patterns to define herself.

Most recently (and curiously at the end of her life) the artist completed a series of paintings representing birth. Based on two forms, a semi-circle across the bottom half of a rectangular sheet and a V extending from the top of the semi-circle to the opposite corners at the top. Similar to her earlier paintings, these forms are of a reclining female body. We do not see a head but are presented with the pregnant belly and legs bent in position to give birth. Sometimes a head emerges from the birthing canal and other times this body lies in wait. The viewer anticipates the subject and, like watching a sunrise, we are sometimes privy to the birth of another being. This final series is remarkable for its simplicity and symbolism marking the conclusion of an extraordinary life.

In her final years, Hurtado’s career experienced a profound rebirth as her work has only recently come into focus for art scholars. The excitement generated by the rediscovery of this artist will certainly continue well into the future.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!