Art on Screen: 12 Movies about Artists Worth Seeing

Whether troubled or exciting, extraordinary or perfectly average, the lives of artists are an endless source of inspiration for cinematographers.

Edoardo Cesarino 17 February 2025

The best of all partnerships is the one within the Arts. Among so many worthy examples, we would like to tell you about the painting Luncheon of the Boating Party, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and the movie Amélie. A charmant French couple, joining forces to reveal to people the beauty hidden in every detail.

In 2002 I was a high school student who loved all things related to France. I remember that year we went to watch a new French movie in its original language. Suddenly I forgot all the distracting excitement, my classmates chatting and texting away. Immediately I was sucked in. I watched without snapping out of it for the whole 121 minutes. The movie was Amélie.

In addition to the wondrous and compelling storytelling, it also featured a painting that held the key to an important process of gaining self-consciousness. The subjects of the Luncheon of the Boating Party, gazing in the background, ignited and witnessed an important exchange between two movie characters.

Despite my enthusiasm, that day I missed most of the dialogue. I loved French, but sadly I wasn’t as good at it as I wished I was. Nevertheless, the suggestive framed corners of Paris, the peculiarity of the narration, the very typical accordion music on the background made my mind soar, while my body was glued to the theater seat.

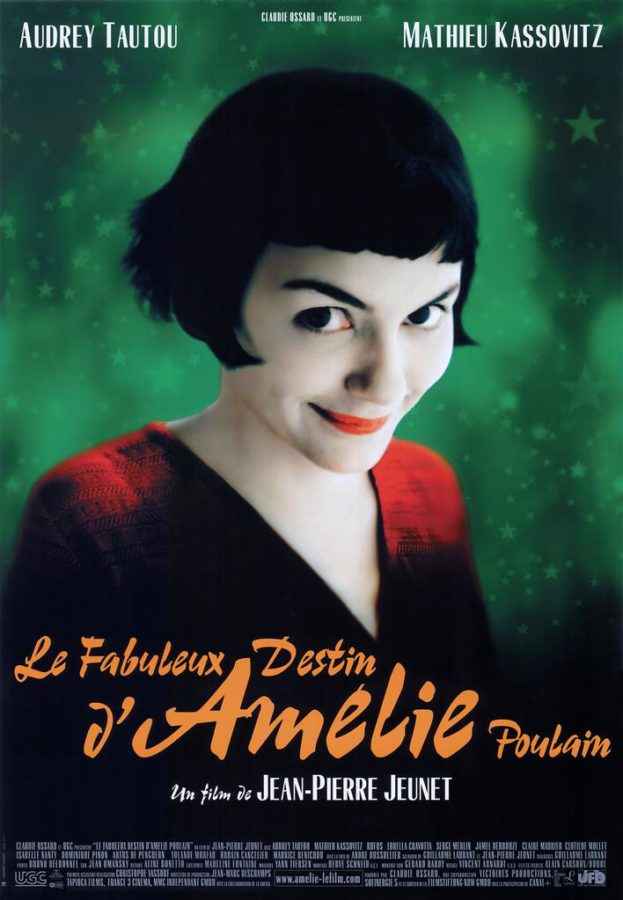

Rating 88% on Rotten Tomatoes, this movie is pretty and delicious, like a macaroon. It scored great critical success and won many awards. A feel-good story full of quirky figures who weave strings of events with beautiful clumsiness. Showing us the perfection of the imperfections. Organically, the young heroine makes no exception.

When she hears the news of Lady Diana in a car crash in Paris, Amélie is deeply moved by it. She makes a vow to devote her life to other people’s happiness. So she embarks on a weird mix of honorable and mischievous adventures around La Ville Lumière.

There are no men in Amélie’s life. She gave it a go a couple of times, but the outcome did not live up to her expectations. On the other hand, she cultivates a particular taste for small pleasures: dipping her hand in a sack of legumes, breaking the crust of the creme brulée with the tip of the spoon, skimming stones on the Canal of Saint Martin.

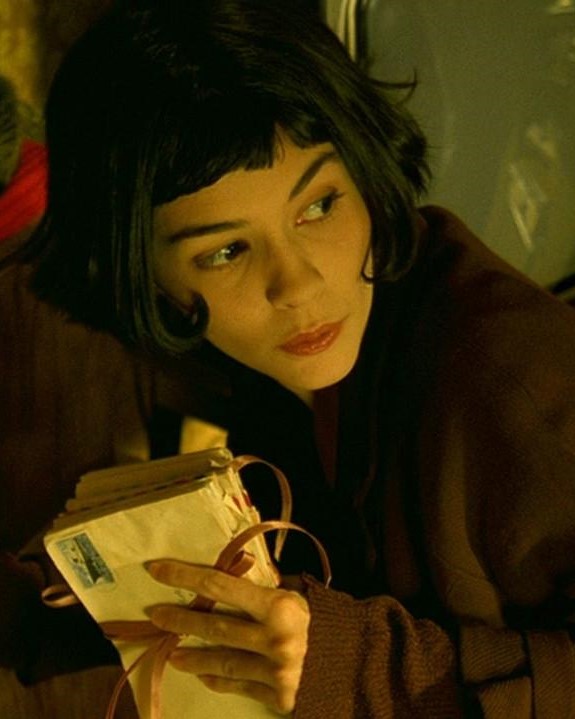

Extract from Amélie, directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001.

When the narrator finishes his introduction of the protagonist, we are left to get acquainted with her. Amélie Poulain, played by the actress Audrey Tautou, stands pale and slim by the window in the kitchen of her apartment in the Parisien borough of Montmartre. She lives there by herself. A single woman working as a waitress in a café. She has big dark eyes framed by thin dark eyebrows, a fringe and a pretty bob. She stares at something.

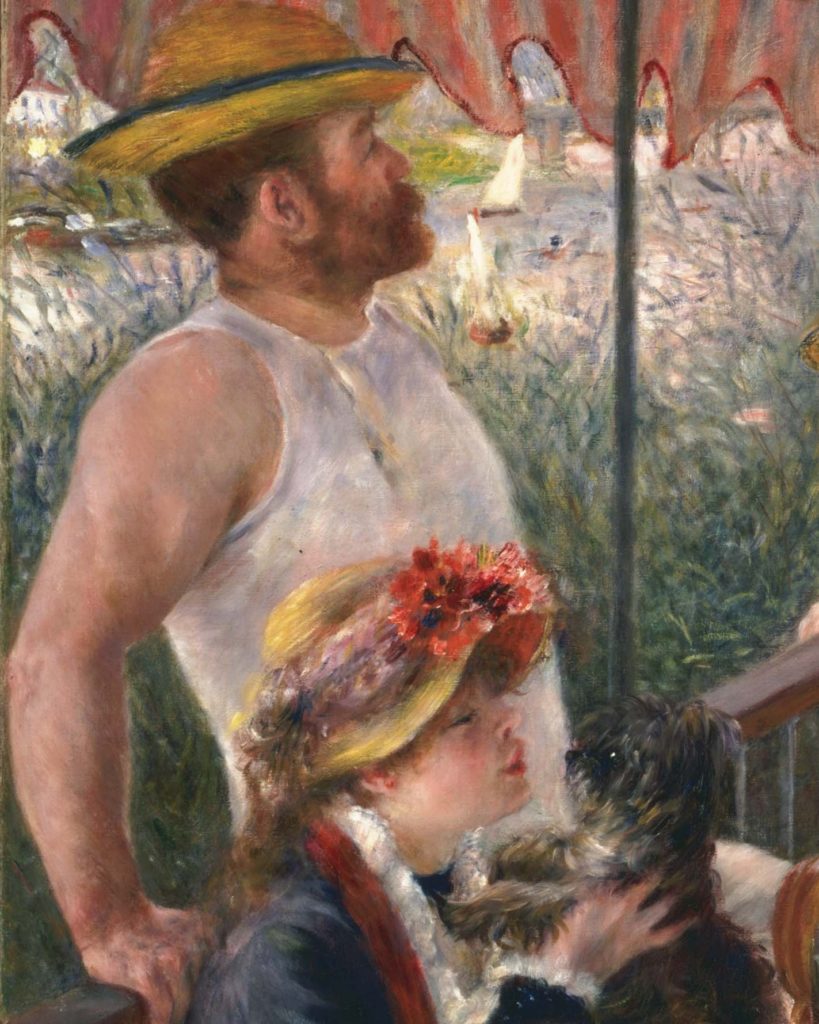

Through the glass, across the building’s courtyard, we notice that she is peeking inside somebody else’s house, at an old man’s back. He is by his own window in his apartment. Bandages wrap around his left hand. We’ll find out that his name is Raymond Dufayel, played by actor Serge Merlin. In the face of the hardship caused by a yet unknown illness, hinted by the necessity of bandages, he holds a brush while sitting in front of a painting: a copy of the Luncheon of the Boating Party, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

This vibrant and colorful oil-on-canvas was painted by Renoir in 1881 and shown at the 7th Impressionist Exhibition in Paris, in 1882. Its French title is Le Déjeuner des Canottiers. The work was most celebrated. Even so, a critic writing for Le Figaro commented that if Renoir could draw better, he would have produced a “nice picture”. Nasty! Check here why!

Mind you, it is true that there is no defined line in sight. However, today that is recognized as quintessentially Impressionistic. Back then, it was seen as a sloppy thing to do: to paint without drawing first. Although the Impressionists never had a common manifesto, they mostly steered clear of the classical study of subjects in preparation of a painting. They elected color as the protagonist, discarding drawn edges and capturing the moment with truthful strokes.

Even though Renoir was part of this new movement, he appreciated the world of the middle class he was born into. He did not seek to paint en plein air as often as others did. Nor did he want to give up the commodities of the french salons as much as Monet or Pissarro. However, Luncheon of the Boating Party is an exquisite example of what fresh air could do to an inspired and exceedingly talented painter.

There are two easily distinguishable sections in this masterpiece. One is on the right of the balustrade, the other is on the left. The first is full of acquaintances and friends of Renoir. The latter is a tribute to the landscape he could not fail to render so beautifully.

The place is the open veranda of the Fournaise restaurant on the island of Chatou, 14 km North-West of Paris’ city center, along the Seine. Young rowers, after their exercise, used to gather there at the time to enjoy the weather, the food, and the company of all sorts of bourgeois figures. The figures include the restaurant owner’s son and daughter and Renoir’s future wife, the lady playing with the black dog. The painting also features artists, journalists and patrons.

Beyond Alphonsine Fournaise, the lady who lounges over the balustrade, there’s the river, glimpses of blue sky, boats sailing in the distance, fronds like a curtain beyond which a serene summer day shows off its light. Above and right of the same character’s head, the contrast between the bright tops of the tall trees kissed by the sun and the blue and purple tones of the bushes in the shade is captured impressively and truthfully. If we look long enough we can almost feel the warmth coming through. We can hear the cheerful chatter and the laughter. We can guess each patch of light and shadow on the skin of the diners, on the fabrics of their clothes. The setting is lively and bursting with colors.

In the middle of such a dynamic scene, Renoir placed a still-life featuring bottles, glasses, fruit, bread crumbs and a wooden flask. A sort of a painting within the painting. Thus demonstrating how the new technique, with its versatility, could totally manage a genre as classic and ancient as still-life. In my opinion, he succeeded with flying colors (pun intended).

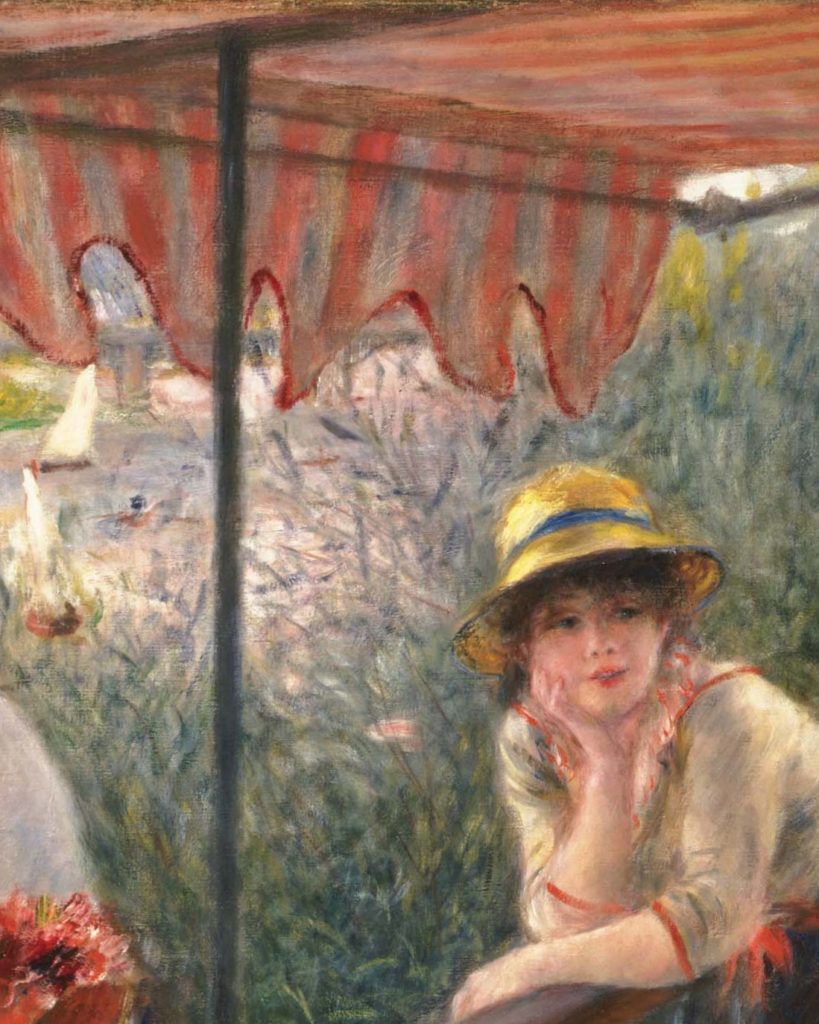

Together with the tables, the balustrade, the stripes of the tent, there are many other lines that our eyes can follow, which articulate this outdoor scene. They correspond to the gazes and interactions between the many subjects represented in the painting. Among the smiling, frowning, pouting young faces, one stands out for its detached and elusive gaze. It is that of Ellen Andrée, theatrical actress and model in paintings of various Impressionists.

Maybe she ponders the next part she has to play at the theater, or she lingers on the memory of a meaningful encounter. Possibly she is trying to sober up. We notice she is drinking a glass of water after what probably was a feast. Either way, it is accurate to say that her body is there, in the midst of the luncheon, but her mind seems elsewhere.

Monsieur Dufayel rescues our heroine after she comes to a dead end with her very first mission. She tries to find the owner of an old tin box full of childhood memories she discovered in her bathroom. A previous tenant must have hidden it behind a tile of the skirting board sometime before and later forgotten it. Determined to return it and make somebody happy, she is in need of help when her neighbor provides her with the name of the person she should be looking for.

In doing so, he unlocks the next chapter of Amelie’s story. He is vital for the success of her new life as a nurse of happiness. He lets her in his apartment and offers her a drink. There is padding on all his furniture. Also, we can see the thick bandages wrapped around his hands again. His nickname is Glass Man, the narrator advises, due to a rare condition that left him with very frail bones. Due to his illness, he never leaves his house. A camera connected to his television and pointed at a clock on the street tells him the time. As it happens, he and Amélie politely spy on each other through their windows throughout the movie.

A copy of the painting we see at the beginning of the movie sits half completed on an easel, in Raymond’s living room. We recognize the faces of Renoir’s original. Surely enough, surrounded by the others, there is Ellen, still sipping water.

“Amélie: I really like this painting.

Raymond: it’s the Luncheon of the Boating Party, by Renoir. Here, I have been painting a copy every year, for the past twenty years. The hardest part is the glances. At times I have the impression they change their looks on purpose, as soon as I turn my back at them, uh? […] Well, after all these years the only person I still struggle to outline is the girl with the glass of water [Ellen Andrée]. She is in the middle of it, yet she seems outside it all.

Amélie: maybe she is just different from the others.

Raymond: uh? How do you mean?

Amélie: I wouldn’t know…”

– Extract from Amélie, directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001.

They gather in front of the canvas and talk about the ups and downs of life more than once. Amélie returns to the subject of Ellen Andrée’s character with her decision, taking her side. Now her fragile neighbor realizes that, by defending the elusiveness of the painted figure, she is truly voicing her own struggle. While the old man’s suffering is en plein air, all around them in his apartment, hers is only just revealing itself.

When Raymond hints that the connection she feels with the water glass lady is perhaps caused by her loneliness, we can pinpoint a pivotal moment in the course of the events. She answers defensively that the lady in the painting might be preoccupied with more important matters. Like helping people or someone who is not there in the scene. So she seems out of context as she pays no attention to the frivolous situation she is in. To that, Raymond fiercely asks: if she consecrates her life to others, fixing their problems, who will take care of her own troubles?

She is very determined, so she stands her ground. Nevertheless, quickly enough some of that loving care she devoted to her neighbors makes a “u turn”. Like a boomerang, it comes right back at her as she starts caring for a young man. Naturally, he is a character full of singular traits. His attention and love will be conquered in the most peculiar and adventurous way imaginable.

Besides the empathy that Amélie feels towards the still, absorbed figure of Ellen Andrée in the Luncheon of the Boating Party, there is a further strong connection between the movie and Renoir. That would be Raymond, his old age, his vexing condition and his passion for painting. They remind us of the Impressionist himself. The Glass Man cannot stop reproducing this piece, year after year. We could guess he does it because of the challenge it poses for him and the pleasure he finds in completing each one of them. So did Renoir as he painted, despite severe arthritis deforming his body until the end of his life.

In conclusion, this magical movie-painting combo is inspiring and uplifting. Both works tell a story full of delightful mystery and effortless beauty. The kind of beauty that, if we take the time to notice and savor it, may be found in each flick of light, in the simple gestures that make us who we are, in the small things that can bring us joy every day.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!