The Art of Ekphrasis: Shakespeare’s Lucrece

It is most common to talk about paintings or sculptures inspired by a piece of literature. Yet, this relationship between arts is not unidirectional.

Jimena Escoto 23 April 2024

Suppose you are not satisfied with any of the historical or fantasy dramas out there lately where all kinds of slander, deception, and politicking occur so that someone, or a faction, may continue to rule a kingdom. If that’s the case, you found the right article. Here, we will be retelling an anecdote once narrated by the ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, while looking at various paintings from different centuries which illustrate it: a tale that explains how the Lydian King of Sardis brought about his own demise by placing his trust in the wrong people and being unable to remain silent about his wife’s beauty. What do I mean by that? Without further ado, let’s explore the story through the brushes of famous painters.

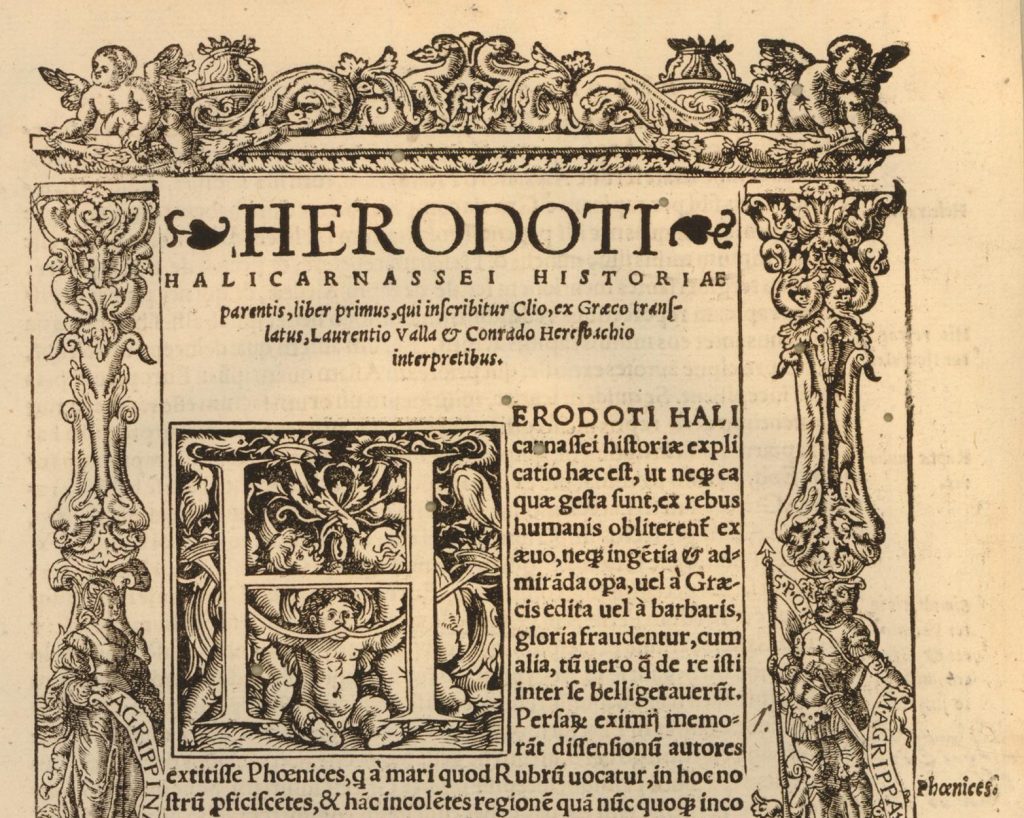

I believe it wouldn’t be fair if we didn’t briefly mention the man who inspired the artists we are going to see in this article. Herodotus was born in the Greek city Halicarnassus, located in the southwest of Asia Minor, which was under the rule of the Achaemenid Empire at the time. According to Souda, a 10th-century CE Byzantine lexicon, he was exiled from the city for being involved in a failed attempt to overthrow the Pro-Persian Greek dynasty during his adulthood. This serious shift in his life naturally sparked his travels and writings.

Published by Eucharius Hirtzhorn, print made by Anton Woensam, A section about Herodotus (Detail), 1526, The British Museum (not on display), London, UK.

In his Histories, Herodotus didn’t only write about the war between the Greeks and the Persians, but also wrote about how they interacted among and with each other. This magnum opus is not a mere war chronicle; from Egyptians to Scythians, he noted the customs and social tendencies of different cultures from different regions. The first section of Histories is where he wrote in depth about the Lydians, and contains the tale we’ll be exploring through art.

Some say that “it’s often better to shut your mouth about the great things happening to you.” I’m sure many of you heard this, or at least some version of it, before: the idea is that good things you encounter or acquire in life tend to somehow collapse once you begin to talk about it openly. For many, it’s just a superstition; for a few, it’s a mysterious occurrence not to be messed with. In any case, this belief is not contemporary and, weirdly enough, we can trace it to Herodotus’ narrative.

Charles Désiré Hue, The Myth of King Candaules, 1864, private collection. Christie’s.

Now, it so happened that the king of the Lydian empire, Candaules, had the most all-consuming obsession with his own wife – so all-consuming, in fact, that he actually believed her to be by far the most beautiful woman in the world.

Candaules was a descendent of Alcaeus, who was one of the sons of Heracles according to Herodotus, making his lineage highly mythical. Yes, you read that right. We are not observing a piece from Thucydides here so you can expect more mythical figures to pop up within the narrative. Anyhow, Candaules had a beautiful wife whose name is unknown to us, though later authors and artists called her Nyssia. While I have always wondered why Herodotus didn’t mention her name (she is a vital figure whose deed acted as the catalyst after all), for the sake of this article and in keeping with tradition, I will refer to her as Nyssia.

William Etty, Candaules, King of Lydia, Shews his Wife by Stealth to Gyges, One of his Ministers, as She Goes to Bed, 1830, Tate Britain, London, UK.

Among Candaules’ bodyguards, there was a man named Gyges. The king had a soft spot for Gyges; he conversed with him about everything, including his wife’s unmatched beauty. However, Gyges never seemed to share the same excitement and conviction as his king when the topic of the queen’s beauty came up. Why would he, right? Of course, he always agreed with him to avoid hitting a nerve as the king was just consumed by this topic. Ultimately, having been dissatisfied with his bodyguard’s dull responses, the king came up with this crazy idea; he wanted Gyges to spy on his naked wife at night. The bodyguard begged his king not to demand this but alas, one simply cannot go against his king’s order. Gyges’ mission was to hide in the royal bedroom, peek at the queen’s beauty, and leave the room quickly and secretly. Guess what happened? He failed miserably.

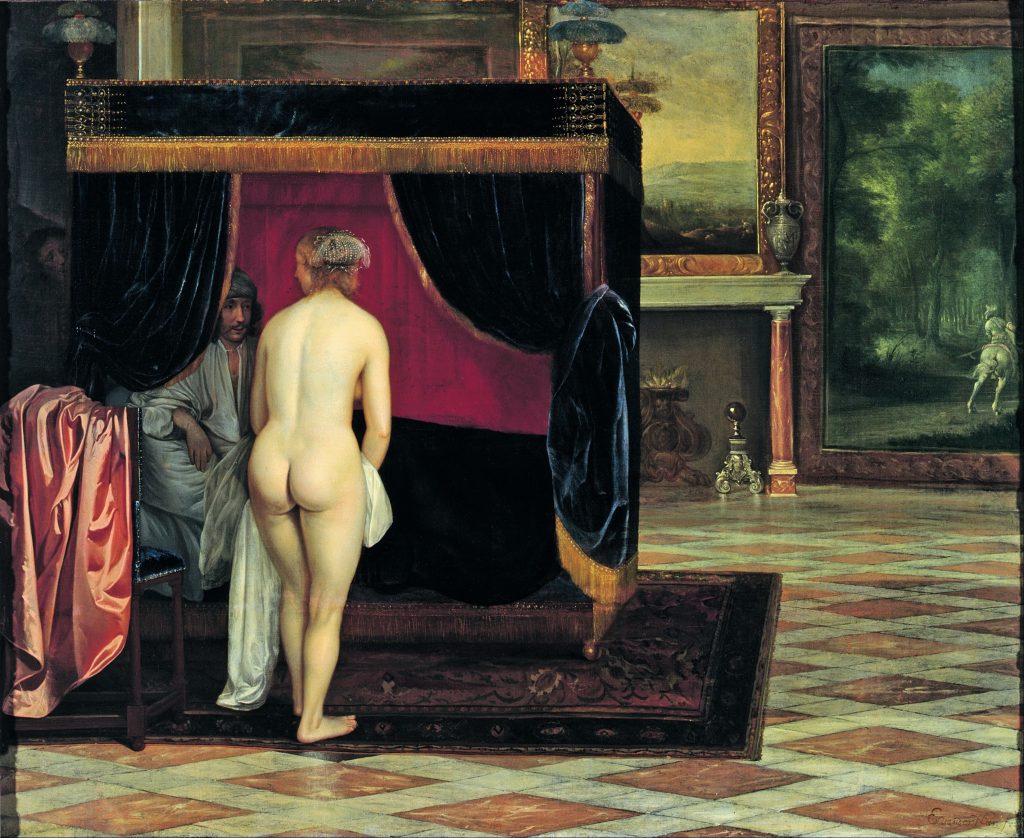

Jacob Jordaens, King Candaules of Lydia Showing his Wife to Gyges, 1646, National Museum of Fine Arts, Stockholm, Sweden.

One of the paintings that I ought to give an extensive spotlight to is Jacob Jordaens’ masterpiece titled Candaules Showing His Wife to Gyges which is currently being displayed at the National Gallery of Sweden. First of all, this is undoubtedly the most famous—and for many, the greatest—Candaules painting that was ever created. One of the most successful artists of the 17th century, Flemish baroque painter Jacob Jordaens was born and died in Antwerp. During his lifetime, he received commissions from many Roman Catholic churches and royals of England and Sweden. Now, what separates this painting from the others? The answer is the brilliant usage of light in the composition: Nyssia, our main subject, is receiving all the artistic aggrandizement, as she should. Yet in other renditions, she is treated just like all the other elements of of the painting, diminishing her significance in both literary and visual aspects.

Unlike other portrayals of the queen, Jacob’s Nyssia is not idealized; she is not meant to possess the beauty of the Goddess Aphrodite in terms of physical attributes or any other semi-divine demeanor that presents her as the purest form of beauty. This realism gives her a distinct character while other portrayals of her seem uniformly painted by the same painter. In Jacob’s portrayal, she is mischievously smiling while posing calmly. Why is this the case? Because she is aware of Gyges’ presence! This is the moment where Gyges failed—one can easily tell he is in serious distress in the background. By including these intricate details, Jacob is able to convey the entire story.

Eglon Hendrik van der Neer, Candaules’ Wife Discovering the Hiding Gyges, 1662, Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf, Germany.

Just like Dutch painters Eglon van der Neer and Nikolaas Verkolje, Jacob preferred to paint the story as if it happened in their historical period. Looking at their paintings you can easily tell that the event occurred probably somewhere between the 16th and 17th century rather than the second millennium BCE. Now, there are two possible explanations for this historical adaptation. First, the information regarding the Lydians was only based on the texts by ancient authors, as the first archaeological excavations in western parts of Asia Minor were conducted much later. Therefore, the artists had no idea about the material culture of Lydians and they may have felt this visual uncertainty would lead to a plethora of inaccurate presumptions within the composition. The other reason might be that by utilizing the characteristics of their period, they may have thought that the paintings could resonate more with the people who lived in the 17th century.

Oh, you may also be wondering why there is a little puppy on the ottoman. No, it’s not there so you can grasp the scale of Nyssia’s bum; good old Jacob merely loved including animals in his paintings! The majority of his paintings have a cat, dog, or bird that often aren’t necessarily tied to what’s happening in the painting.

Nicolaas Verkolje, Gyges in the Bedroom of King Candaules’ Wife, 1675, The Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, Slovakia.

Although Nyssia was aware of Gyges’ presence in the royal bedroom during that night and was angry with the situation, she didn’t let the anger overcome her. She pretended everything was all right. But why was she angry in the first place? Here’s why according to Herodotus:

for among the Lydians, as among most other barbarians, it is such a taboo to be seen naked that even a man considers it a humiliation.

Instead of taking her anger out on King Candaules and his guard Gyges in an old fashion way, Nyssia decided to adopt a more strategic approach to the situation. Not long after that night, she called Gyges to her room and gave him two choices; either to become the new king by killing Candaules in his sleep and marrying Nyssa, or to be killed that very moment by her dagger.

One of two people must die: either the man whose idea this whole business was, or else the man who saw me naked, in defiance of all propriety.

Good old Gyges, who loved his king faithfully, chose the former and became the new king. What would you have done in his position?

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!