Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

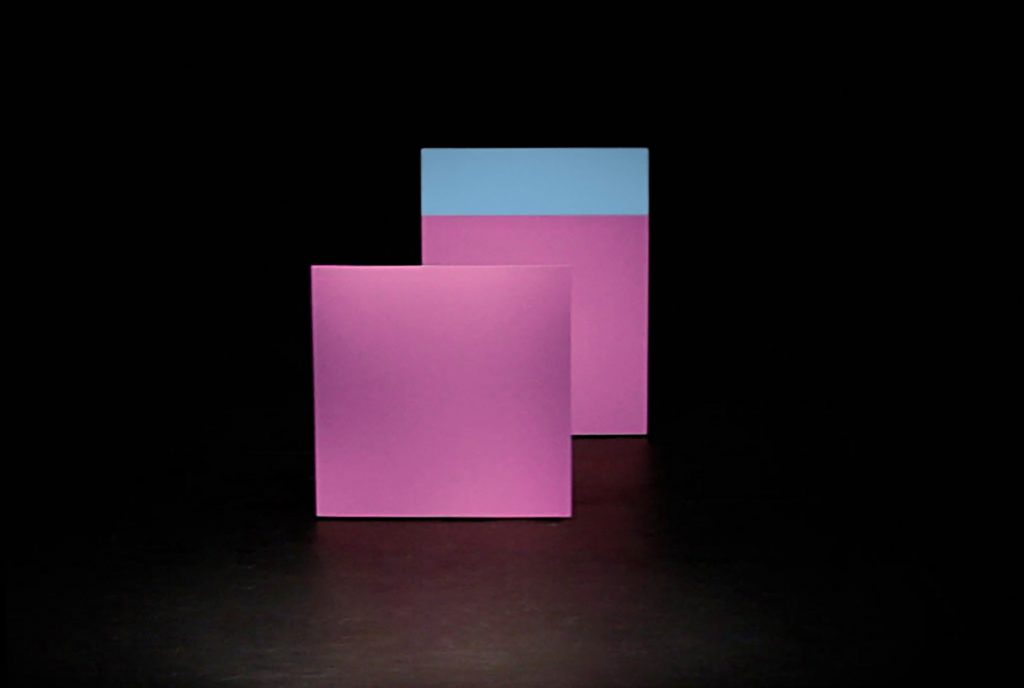

Breaking with all the patterns of what had been art in Latin America up to then, Lygia Pape with Grupo Frente created a unique Brazilian artistic movement: Neo-Concretism.

Art is the manifestation of human history and man is the product of his context. Therefore, the artist is at the same time the creation and creator of their historical moment. Indeed, it is in this sense that we can observe the expression of an artistic movement that is genuinely Brazilian. But also the range of devices and sensory experiences in the artworks of artist Lygia Pape.

Lygia Pape was born in January 1927 in Rio de Janeiro state, where she later died in 2004. She graduated in philosophy from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in the 1960s. In the 1980s she became a Master of Philosophical Aesthetics with a scholarship from the Guggenheim Foundation in New York. Her life is also marked by a career in various domains. She was a teacher at Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ) and at the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage. She taught art classes at the University of Santa Ursula at the School of Architecture as well.

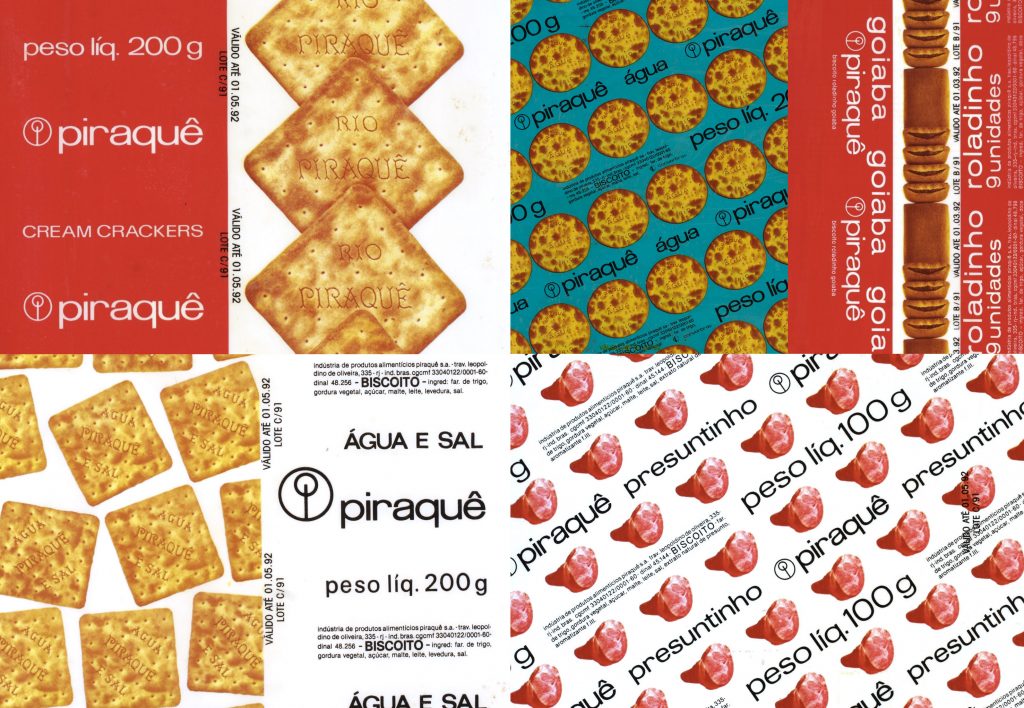

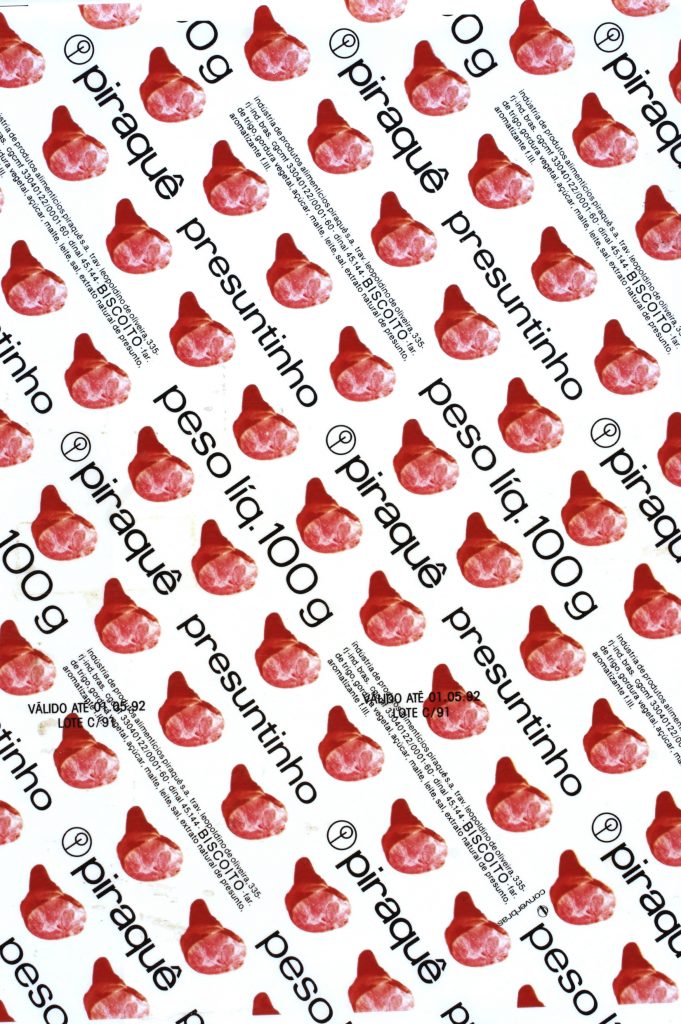

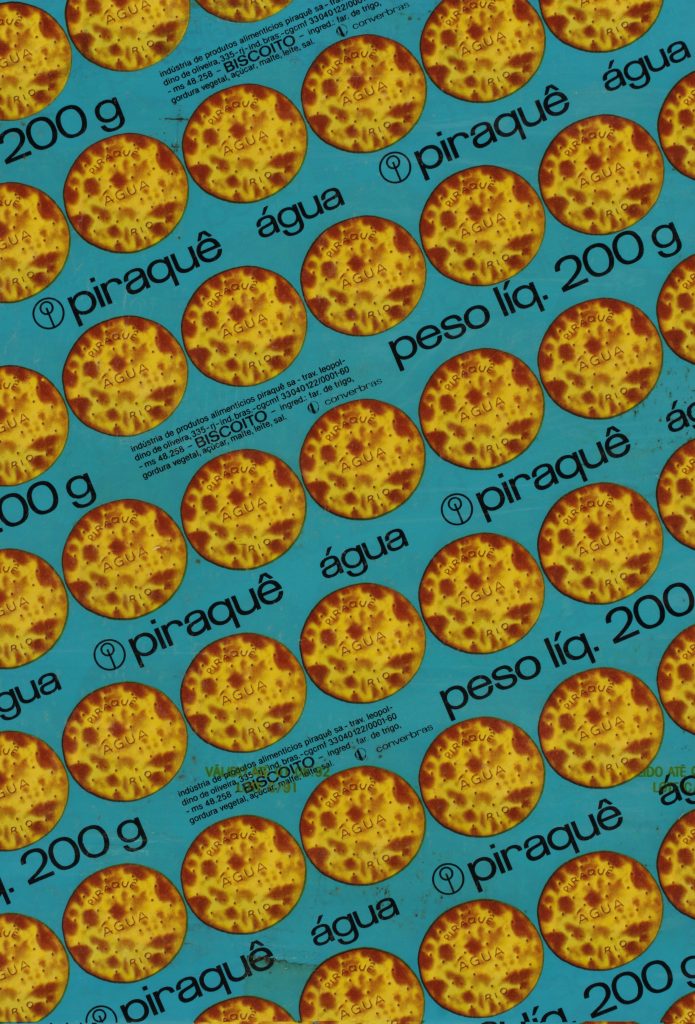

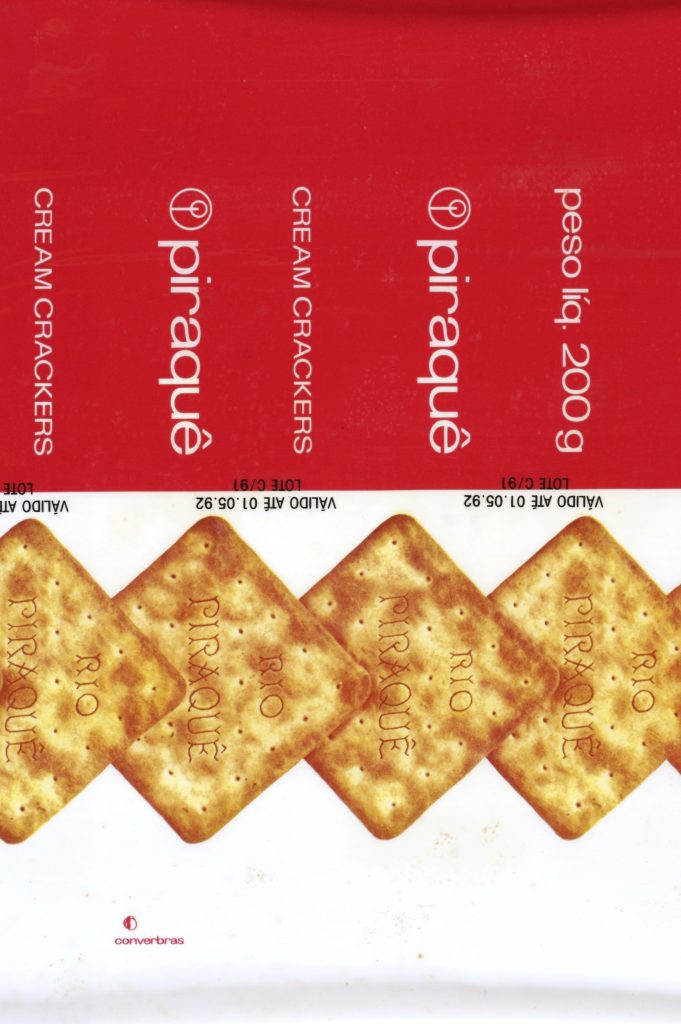

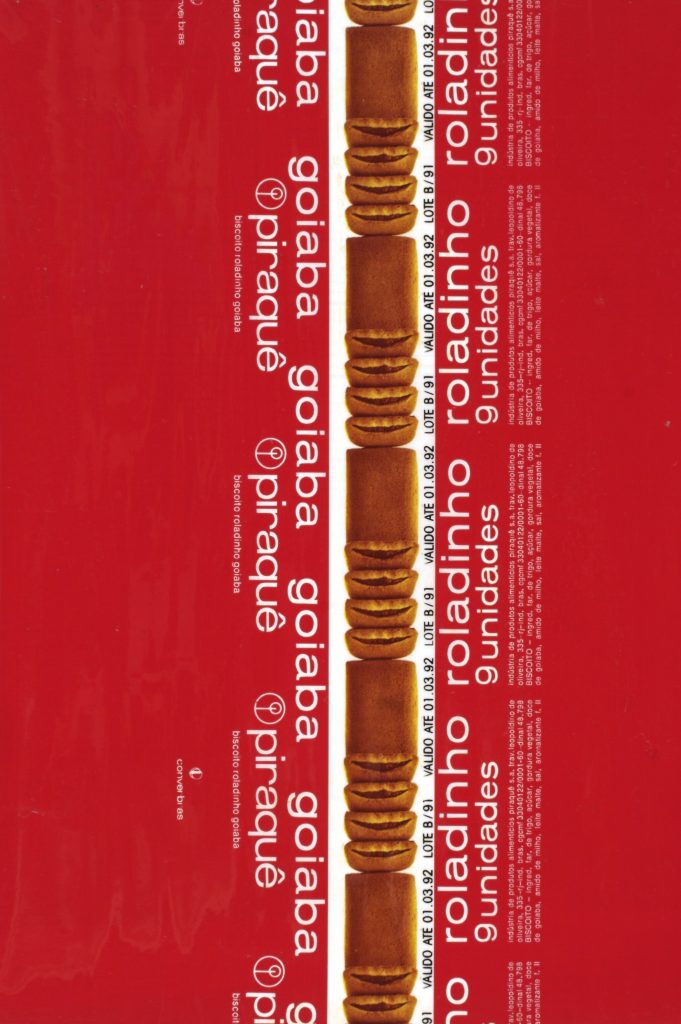

Moreover, as a designer, she developed the layout of cylindrical packaging. This format was soon adopted internationally, transforming cookie packages into what we know today. In particular, she also created the logo and product displays for Piraquê from 1960 to 1992.

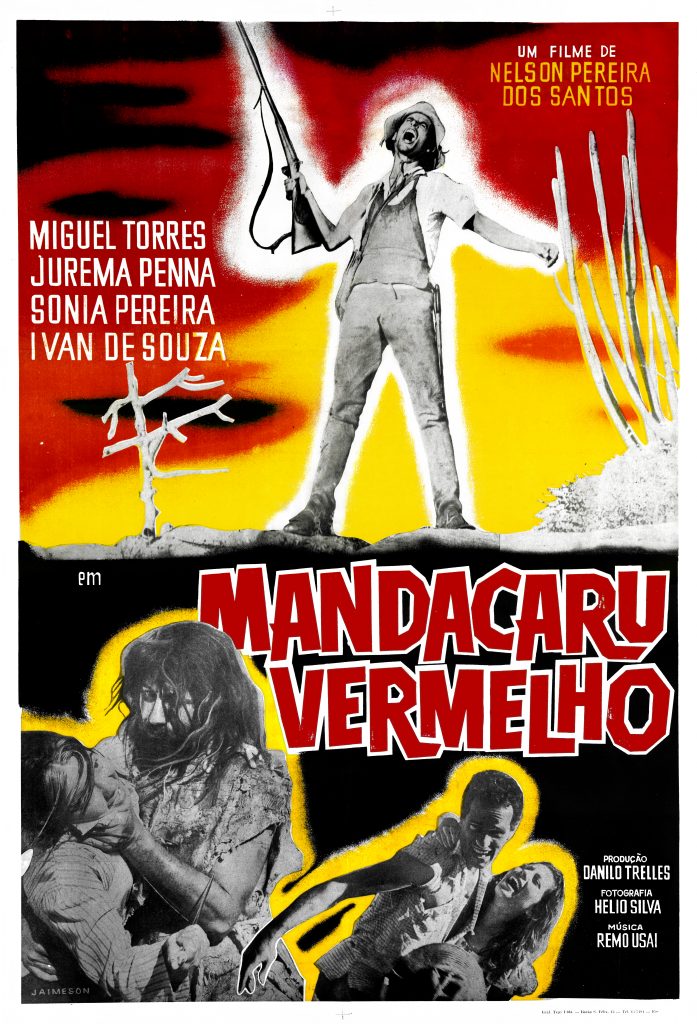

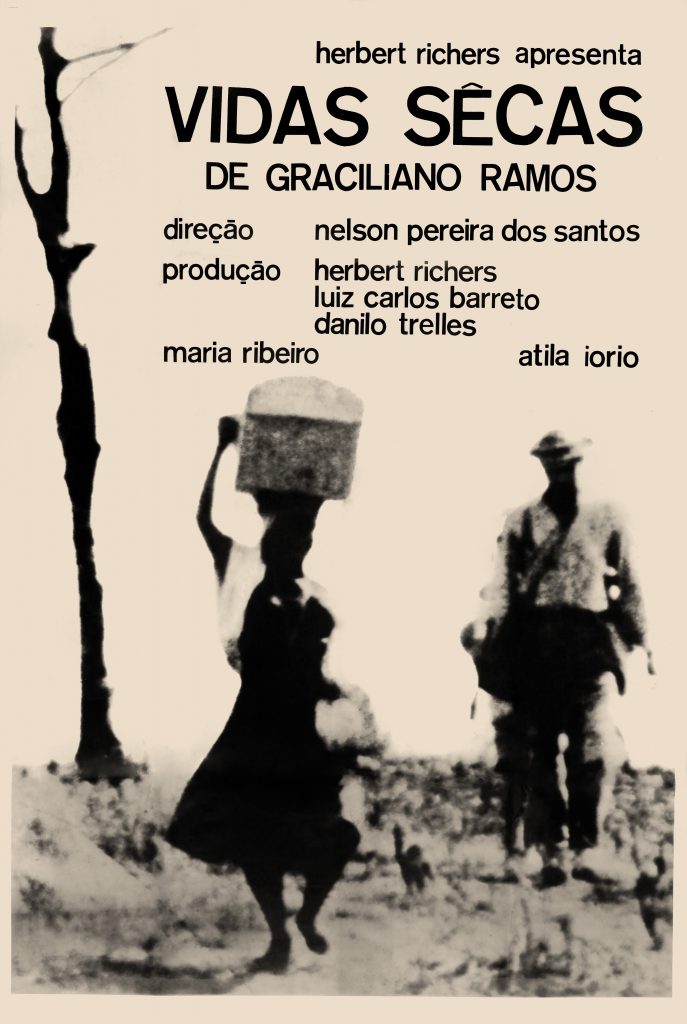

Furthermore, Lygia Pape created several posters for films of Cinema Novo, a Brazilian cinematographic movement of the 1960s. Vidas Secas and Mandacaru Vermelho by Nelson Pereira dos Santos, for example.

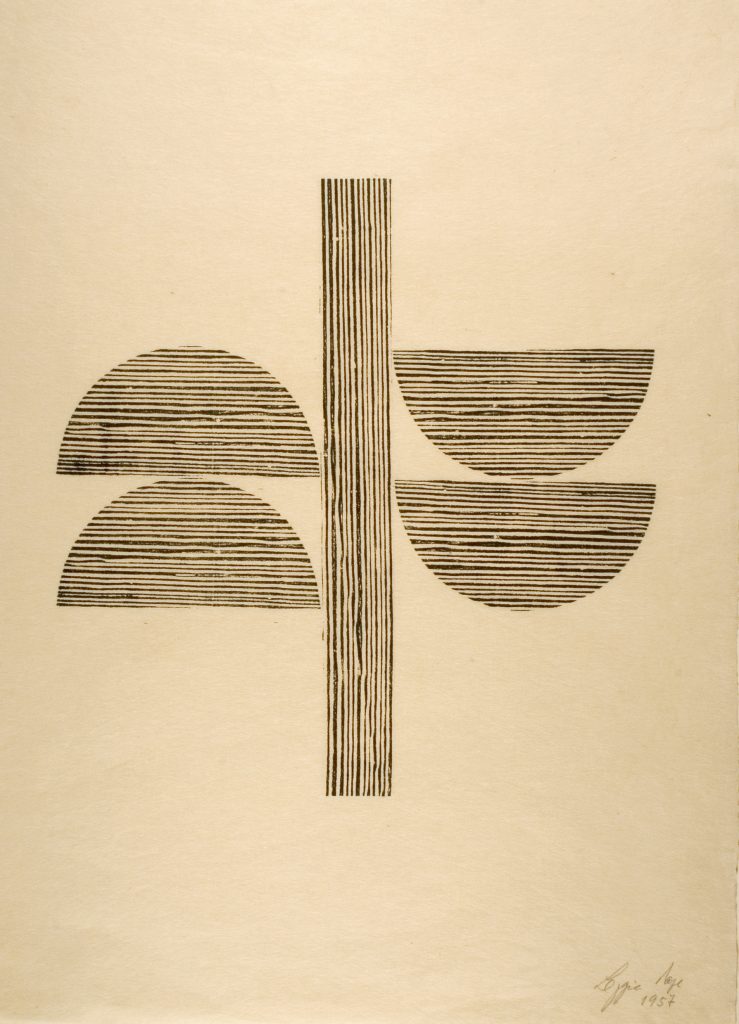

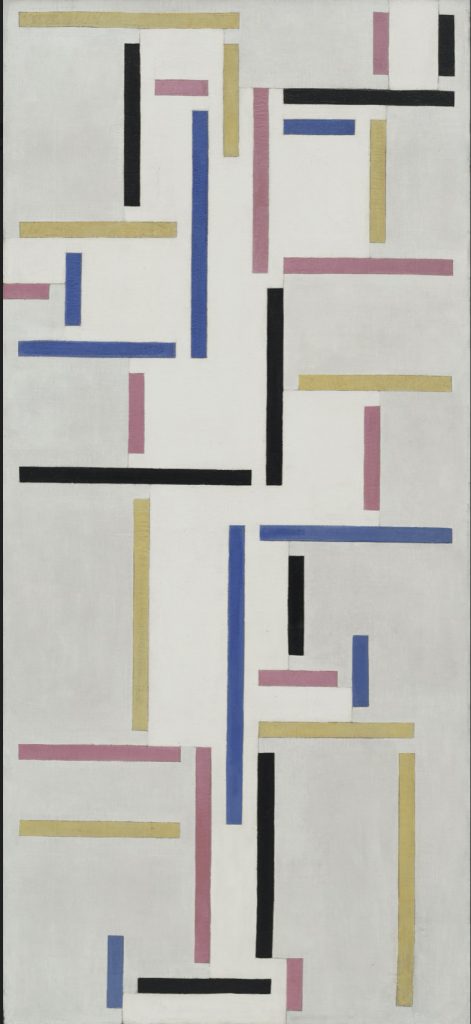

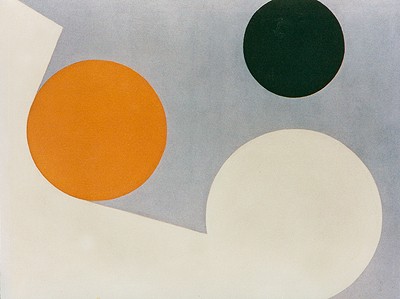

In 1952, she began working with xylography, which can be seen in her series titled Tecelares. Later, she branched out into other disciplines such as painting, sculpting, performing, film direction, and multimedia. When her professional career advanced, she joined the Grupo Frente, led by Ivan Serpa. This group is responsible for publishing the Neo-Concrete Manifesto, a text which she co-wrote, then giving birth to the Neo-Concretism movement.

Her works, above all, permeate the research of new languages and relations within the public space. Consequently, they have a political and innovative imprint.

As proposed by Vanessa Rosa Machado, in The Art and Public Space in Lygia Pape’s Films, three different periods of her production can be observed. Her analysis is mainly about her film production, but the hybrid character of some of her works also allowed image records.

The first period of her work is marked by the utopia of the modern cultural project from 1950 to 1959. The second – lasting until 1968 – was still the desire to rebuild the city and its bodies. Finally, the third from the 1970s onwards assumes the eyes of the existing city that has undergone sudden and critical changes due to the military dictatorship.

At that time, the world was increasing industrial production due to the Cold War. Soon, television became popular and was used for the diffusion of mass production of consumer goods. As a result, it directly affected the aesthetics and customs of the time. The idea of modernity was geared full steam ahead, and certainly, Brazil was on board.

The effects of this modern wave of technology were mainly traced by great transformations in a short period in the country. In five years, important cultural institutions like MASP (1947), MAM of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (1948), and the Bienal de São Paulo were created.

Owing to “Americanization” the country definitively broke with European cultural paradigms, mainly cultivated by the French since colonial times. For the first time, it saw private initiative assuming the role of cultural responsibility that had always been delegated to the state.

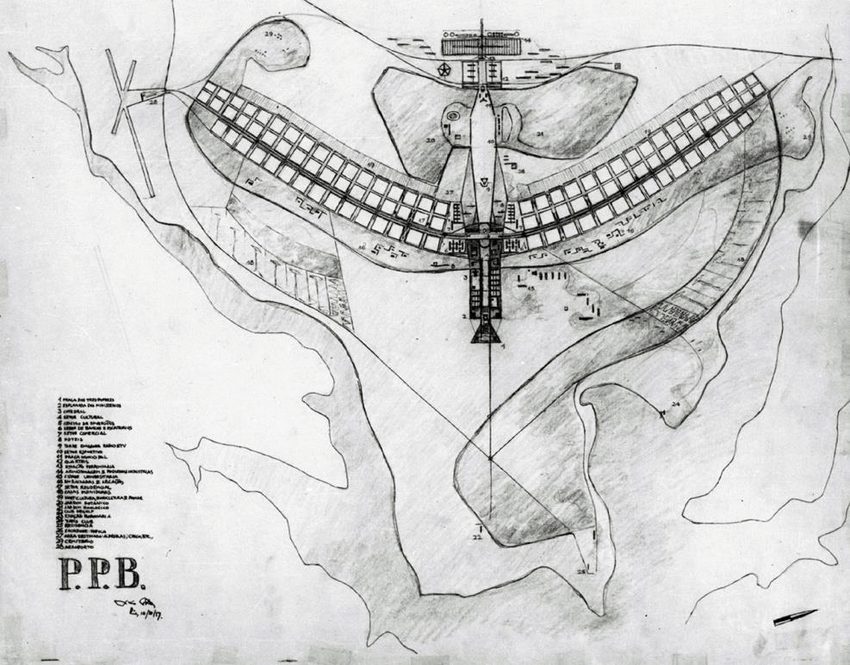

Another point is that this decade resulted in important intellectual and artistic segmentations. Mainly due to the utopian proposition of a new country with the construction of the new capital, Brasilia.

Brasília Projeto Piloto and Congresso Nacional, Photograph by Chronus via Wikimedia Commons.

Brasília Projeto Piloto and Congresso Nacional, Photograph by Chronus via Wikimedia Commons.In this context, the propagation of international vanguard arts in Brazil kindled an artistic need for the renewal of previous artistic movements. The Concrete groups Ruptura and Frente were born. One in each of the main modern poles of the country, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

According to Cocchiarale in Between the Eye and Spirit, these groups differed from international art movements such as American Abstract Expressionism, European Formal Abstraction, and Tachism. However, the cause of this difference is that the Brazilian territory was more favorable to the birth of a vanguard due to the social-political context between the 1950s and 1960s. Above all, Brazilian artists searched for themes that touch on national, regional, social, and allegorical issues.

The São Paulo group Ruptura had a stricter idea of the principles of Concretism, as proposed in 1930 by the artist Theo van Doesburg, and later in 1935, by Max Bill. This group was composed of Lothar Charoux, Hermelindo Fiaminghi, Geraldo de Barros, Judith Lauand, Luiz Sacilotto, and Waldemar Cordeiro.

On the other hand, the group from Rio de Janeiro, Frente, was formed in 1953 by the artists Amílcar de Castro, Aluísio Carvão, Décio Vieira, Ferreira Gullar, Helio Oiticica, Ivan Serpa, Lygia Clark, and Lygia Pape. Their works were directly in contrast to that of the group from São Paulo and valued the specific and personal character of their experiences.

In short, this divergence created a tense atmosphere between them. At the First National Exhibition of Concrete Art, after a debate about their differences in front of the press, finally, the artists of the Grupo Frente decided to break with the Ruptura. As a result, in 1959, they created Neo-Concretism, a unique and authentically Brazilian movement.

It was this rebellious spirit of the Brazilian vanguard in the fifties and sixties that enabled it to penetrate deep into ideas of European abstraction without any overly respectful ceremony or feeling of inferiority.

Guy Brett: A Lógica da Téia in Gávea de Tocaia / Lygia Pape, São Paulo, Cosac & Naify Edições, 2000.

Thus, the Neo-Concrete vanguard created its foundation in experiences. So, they ended up beating the dilemma of Western art: to create works that sustain themselves in a sensorial and intellectual way.

Fernando Cocchiarale: Entre o olho e o espírito (Between the eye and the spirit). Accessed October 29, 2020.

Vanessa Rosa Machado: A arte e espaço público nos filmes de Lygia Pape (Art and public space in Lygia Pape’s Films). São Paulo: revista de pesquisa em arquitetura e urbanismo programa de pós-graduação do departamento de arquitetura e urbanismo eesc-usp, 2008. Accessed October 29, 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!