Apollo and Daphne in 5 Artworks

From Ancient Rome to the Renaissance and Rococo, the timeless appeal of the Apollo and Daphne myth spans centuries of artistic expression. The myth...

Anna Ingram 30 January 2025

18 December 2024 min Read

You’ve heard of the larger-than-life Impressionists who captivated Europe and the world at large with their dazzling light and color. But what about the group of exceedingly talented and progressive Italian artists who preceded the French rebels by more than a decade? Meet the Macchiaioli, the revolutionary Italian Impressionist painters you’ve never heard of.

Active in Tuscany in the mid-1800s, the Macchiaioli emerged during the political and social movement for Italian unification. The Macchiaioli painters became synonymous with the revolutionary spirit of the Risorgimento, which culminated in a unified Italy under one flag and one government. Armed with their paintbrushes, these innovative and experimental artists fought to unite their country through their art. A group of young Italian patriots from around the peninsula, the Macchiaioli included such artists as Giuseppe Abbati, Cristiano Banti, Vincenzo Cabianca, Adriano Cecioni, Vito D’Ancona, Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, and Telemaco Signorini.

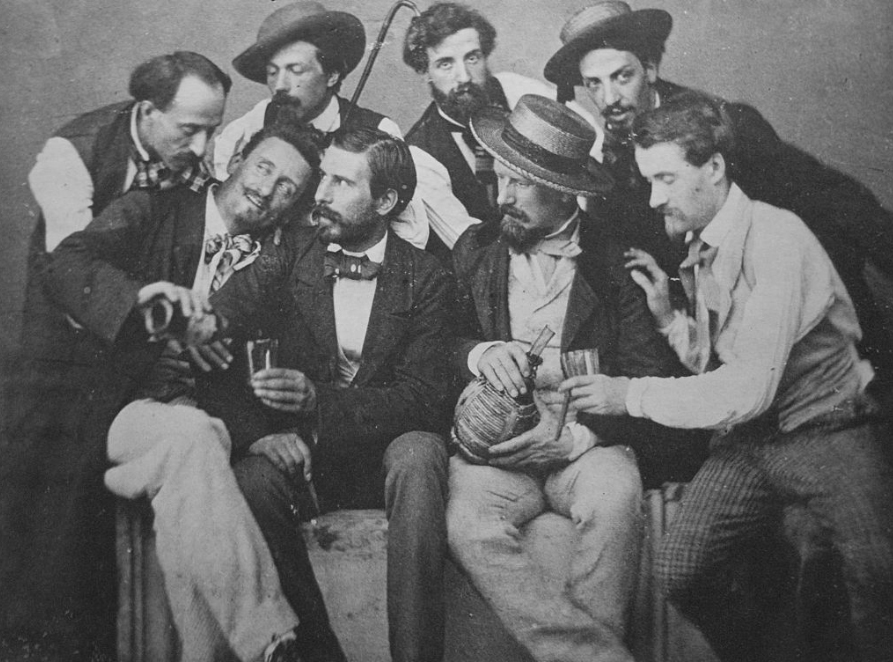

Members of the Macchiaioli at the Caffè Michelangiolo. c. 1856 Art Escape Italy.

While bombshells and bloodshed plagued most of Italy, Florence was a safe haven for political exiles and refugees. The Caffè Michelangiolo became a meeting place for bohemians and radicals united by the desire for rebellion and the will to subvert rigid academic rules. It was common for intellectuals to exchange ideas of art theory and politics “amidst the smoke of pipes and jokes.”1

Telemaco Signorini, Street of Ravenna, 1875. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

At a time when Neoclassicism and Romanticism prevailed in art, the Macchiaioli proposed a new way of seeing. They recoiled from the canons of academic art and the official Florentine Academy, where many of them had studied. Instead, they wished to reinvigorate Italian art, restoring a relationship with nature and daily activities. They painted that which was real, and in doing so conveyed truth and simplicity. Subsequently, the Macchiaioli moved away from historical and literary themes, turning to depictions of everyday life in Italy.

Silvestro Lega, After Lunch (The Trellis), 1868, Palazzo Brera, Milan, Italy. Bold Brush.

I would like to see art free from certain prejudices which could be very harmful to us over time. I would like to see a more splendid art, treated with self-confidence, easier, without renouncing the desired qualities now known to artists in progress.

Letter to Vincenzo Cabianca, 1875

The Macchiaioli painted with bold patches of colors, resembling spots. They often worked with an intense chiaroscuro, leading to the isolation of brighter colors. Their name derives from the Italian “macchia,” which roughly translates to “splotches”. The Macchiaioli—a label coined by the conservative Catholic newspaper Nuova Europa in 1862—believed the effect of their works should derive from the painted surface, but critics simply thought their paintings looked unfinished.

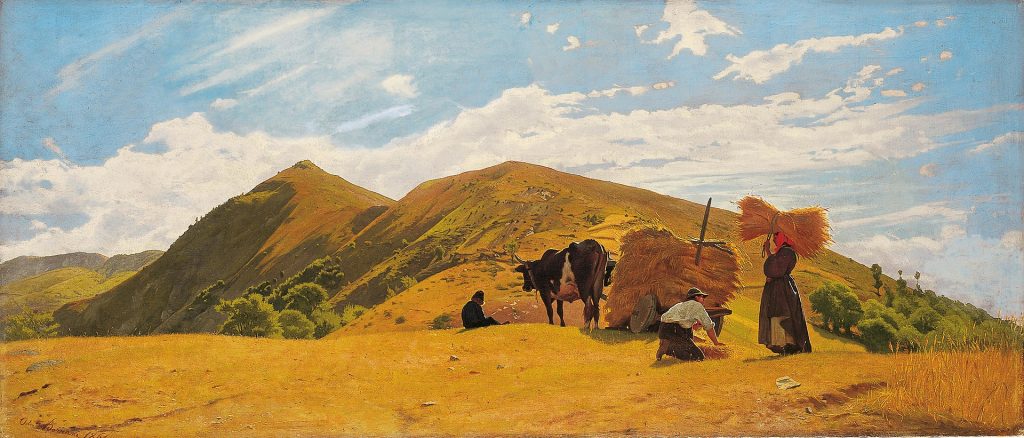

Odoardo Borrani, The Wheat Harvest in Castiglioncello, 1867, Istituto Matteucci. Wikimedia.

While the Macchiaioli are often likened to the Impressionists, significant differences exist between the two movements. Firstly, it is important to note that the Macchiaioli predate the Impressionists by almost a decade, active around the year 1850, whereas the first Impressionist exhibition was held in 1874.

Like the Impressionists, the Macchiaioli sought to break free from academic art, focusing instead on scenes of everyday life. Yet, while the Impressionists were keen on capturing leisurely entertainment and industrial progress in society, the Macchiaioli tended to celebrate peasant life and their works were charged with political undertones.

Silvestro Lega, The Visit, 1858, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rome, Italy. Fundación Mapfre.

Members of both movements preferred to work outdoors, en plein air, noting the importance of the direct observation of nature. While the Macchiaioli made preliminary sketches outdoors only to complete their paintings back in the studio, the Impressionists made use of the newly-invented portable paint tubes, which facilitated the completion of their paintings on-site. As Pierre-Auguste Renoir once stated, “Without colors in tubes, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Pissarro, and no Impressionism.”2

Silvestro Lega, The Education for Work, 1863, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Many of the works by the Macchiaioli are intimate scenes with echoes of Tuscan art of the quattrocento. At the same time, they are marked by a certain grittiness. Much like the Impressionists, the Macchiaioli drew inspiration from Realist artists like Corot and Courbet, from the acclaimed Barbizon School.

Silvestro Lega, The Song of a Starling, 1868, Gallery of Modern Art, Florence, Italy. Meister Drucke.

Women of all social classes—salonnières and peasants alike—play a central role in the works of the Macchiaioli. Women are shown as the pillars of the family. They are depicted as strong, independent, and active, and they take center stage in many of their works. The Macchiaioli placed particular emphasis on the dignity of ordinary women such as mothers, field workers, seamstresses, and musicians.

Odoardo Borrani, Women Stitching Red Shirts, 1863, Private Collection. DeArtiBus.

Odoardo Borrani’s Women Stitching Red Shirts (1863) is a clear display of domestic patriotism at a time of political upheaval in Italy. The viewer steps into a home where middle-class women sew the famous red shirts that would later become emblematic of Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882) and his liberation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies from Spanish Bourbon control in 1860.

The Italian Macchiaioli never received the same international acclaim as their French counterparts. This is due in large part to the Macchiaioli painters’ relatively brief period of artistic activity. In fact, each member of the group went in his own creative direction after 1862. Most of the works by the Macchiaioli are not on public display but rather hang in private collections throughout Italy. The movement was largely rediscovered thanks to Italian novelist and art critic Anna Franchi, who in 1902 published one of the most important documents about the Macchiaioli, Tuscan Art and Artists from 1850 to Today.

Odoardo Borrani, Wheat Harvest in the Mountains of San Marcello, 1861, University of Siena, Siena, Italy. WikimediaCommons (public domain).

[…] their movement, the first flowering during the modern period of a truly indigenous Italian art, was […] inescapably the product of their own time and place, a reflection and a consequence of their country’s stormy political and social history and its unique cultural heritage.

The Macchiaioli: Italian Painters of the Nineteenth Century

The Macchiaioli movement remains inextricably tied to the social context in mid-19th-century Italy. Theirs was an artistic current that moved Italian art in a more modern direction. Their desire as Italians to break free of foreign rule went hand-in-hand with their mission as artists to break free of the restrains of academic formalism. The Macchiaioli also helped construct a new national identity through a revolution made of light and shade. In fighting for a unified Italy, they left their mark—or macchia—on the history of art.

Vincenzo Cabianca, Sul Mare, 1864, private collection. Macchiaioli Pisa.

Anna Franchi, I Macchiaioli Toscani (Garzanti, Milan, Italy, 1945).

Jean Renoir, Renoir, My Father (Little, Brown & co., USA, 1962).

Norma Broude, The Macchiaioli: Italian Painters of the Nineteenth Century. Yale University Press, 1988.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!