Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

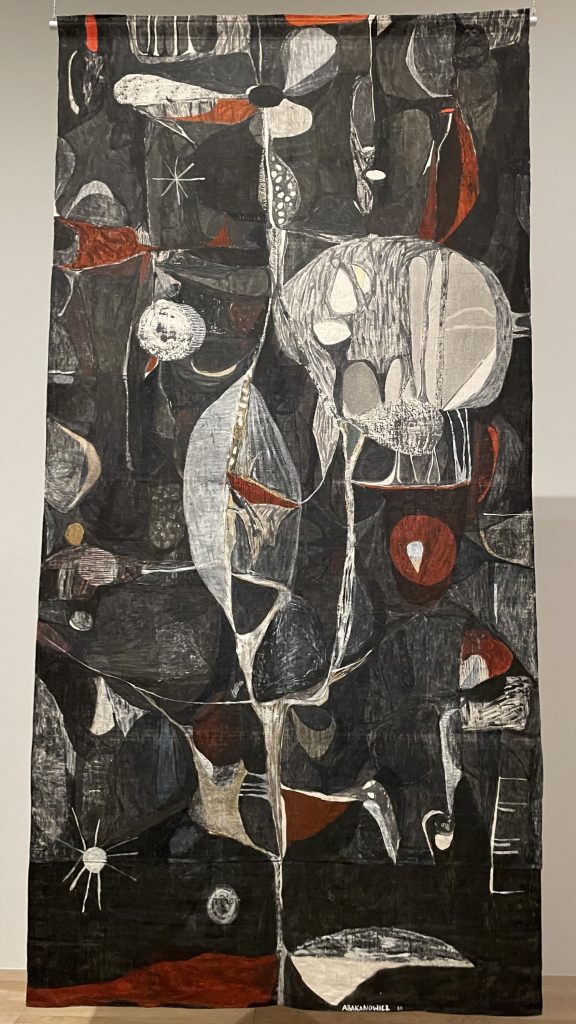

A beautifully curated exhibition at Tate Modern, in London, UK, explores the transformative period in the career of Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz. Tate makes full use of the gallery space in the Blavatnik Building to show us Abakanowicz’s mesmerizing textile structures that were, and still are, so confusing to art critics that they called them abakans because they could not easily be classified as tapestries or sculptures.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

Art is a state of being. You are born with the capacity to integrate your energy into objects.

Abakanowicz was born in 1930 to an aristocratic family. She spent her early childhood in the countryside in close contact with nature. When she was nine years old, the Second World War started, and that experience deeply marked her, though she never presented herself as a victim. After the war, she pursued artistic education, eventually studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Given that Poland was, at that time, a communist country, Abakanowicz’s noble origins became an issue and she had to hide it to get a place at the academy. She studied painting, but some of the optional classes included weaving. During that time, artists in Poland were forced to follow the doctrine of “Socialist realism” in their art. This rigidity possibly made Abakanowicz turn from painting, which was closely watched by professors and censors, towards other more niche mediums of weaving and tapestry.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

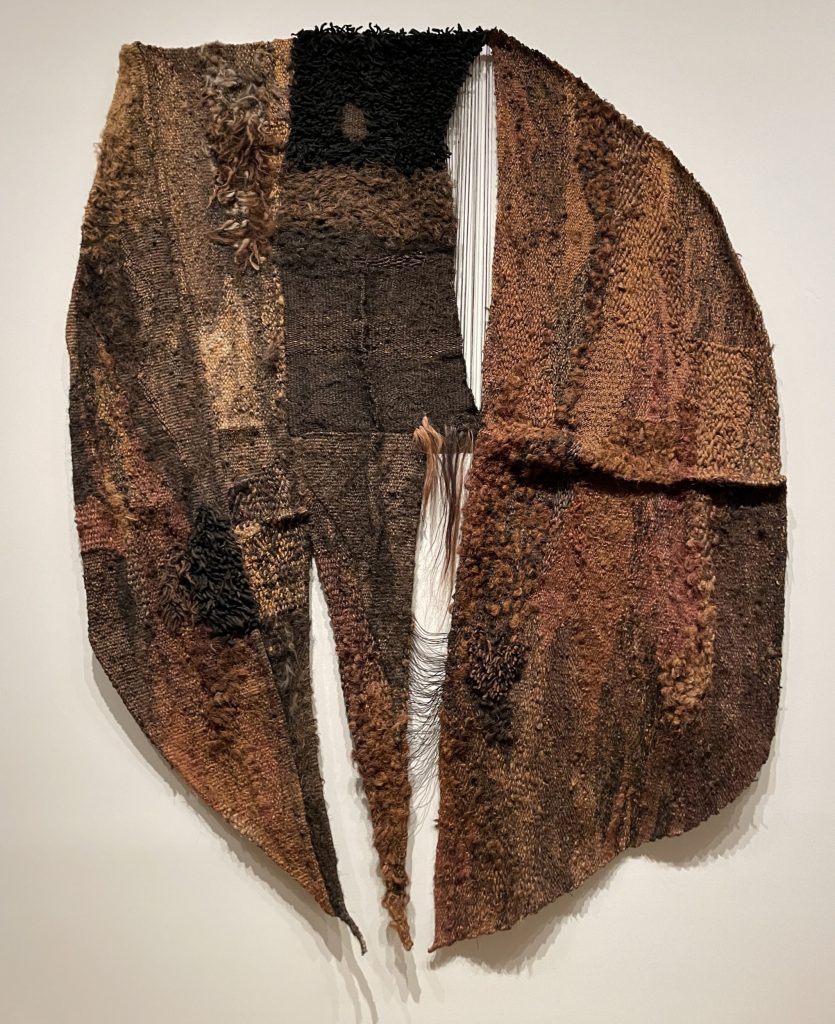

Initially, she followed the classic way of weaving, sticking to the two-dimensional rectangular forms that the medium naturally invites. Even at that stage, her way of working was revolutionary, because she refused to work off of a cartoon, and improvised her works, rather than pre-designing them. Her energy and imagination needed something more, so she started experimenting with breaking the rigid forms, first still in two dimensions, by departing from the rectangular forms towards more rounded shapes. Only to continue down the path of exploration and gradually start exploring the potential of textiles in three dimensions. Eventually, she made the radical step of separating her weaving from the supporting walls and from the tyranny of the parallel warps. She started weaving in any direction within three dimensions. This is how the abakans were born, part tapestries and part sculptures, but mostly expressions of artistic freedom in a system that allowed none.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

How did Abakanowicz get away with this? Certainly, the medium she chose was helpful in avoiding the attention of censors, as weaving has been considered “woman’s art” and therefore secondary and closer to a craft than art. Another thing was the organic nature of her works, many things could be said about them, but they certainly had no overt political message.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

The exhibition at Tate Modern, curated by Ann Coxon, explores this transformation in Abakanowicz’s work. We can observe her early works gradually trying to liberate themselves from walls, fighting their rectangular forms. The echoes of Abakanowicz’s childhood and the relation to nature come back in a series of smaller works, some of them also related to the war traumas. But none of this prepares us for what is to come.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

As we enter the central space of the exhibition, we are faced with a huge oblong form, very organic shimmering between black and aubergine. In the air, we can smell the sisal, wool, and horse hair, a very unusual smell for an art gallery, but one that, even if not really pleasant, transports us away from the gallery into the mysterious natural world. The work looks forbidding and inviting at the same time. It is the first of the abakans we are about to see.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

Abakanowicz actively participated in how her works were exhibited. She consciously grouped and clustered them to create “situations” or “environments” as she called them. Here, the works are exhibited in the same spirit, hovering in mid-air, sometimes even slowly moving with the passing air and creating a forest that we are invited to explore. Abakanowicz said those works are her expression of the need for safety, the memory of hiding in a hollowed-out tree as a child and watching the world from the safety of the trunk. And this is one thing missing in this exhibition – the physical contact with the works. Because they are tempting to touch, to enter, and let the thick folds close behind us, drowning out all the noise and distractions of the modern world. Given the fragility of the medium, it is out of the question, and yet it feels so tempting to just wrap oneself into those protective forms.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

Abakans were not the only artworks shown in the exhibition in 1969. Abakanowicz, together with avant-garde director Jarosław Brzozowski and experimental composer Bogusław Schäffer, created the movie Abakany. Here her works float magically in the desert-like space, making it all feel other-worldly, as if abakans were some alien life form. As if in the movie, we see them in their natural habitat and what we can see in the gallery is a mere glimpse of their full splendor.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

While Abakanowicz never openly talked about the climate or feminism, her works send a clear message on both. When other materials were difficult to source, she would prowl the banks of the Vistula river to gather discarded sisal ropes to use in her works. Of course, climate change was not an issue discussed at the time, but the relationship between humans and nature was certainly an area that she explored in her works. The connection to nature that she had in her childhood, combined with her perception of that time as the safest in her life, created a strong emotional bond that resonates in her works.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

Her works are also often included in the exhibitions of more feminist approaches. Again, Abakanowicz never openly declared to be a feminist, but her works speak for themselves. She took a medium always perceived as secondary and a craft, not an art, because it was a domain of women, and elevated it in her works. Abakans are so monumental that they could no longer be dismissed as tapestries or mere decorations, they are art. They did not fit the traditional concepts of art and that was exactly what Abakanowicz set out to do. She took the form that was only bound by the rules of the medium, but not bound by many expectations, and made it her own. Her interest in the organic and the bodily shines through her works. At the same time, she puts those topics in the center, not letting anyone dismiss them.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Every Tangle of Thread and Rope exhibition view, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Joanna Kaszubowska.

The exhibition explores a specific period in Abakanowicz’s long career and glosses over her later works, which gives this show focus and lets us fully explore the majesty of abakans.

Every Tangle of Thread and Rope

Tate Modern

Until May 21, 2023

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!