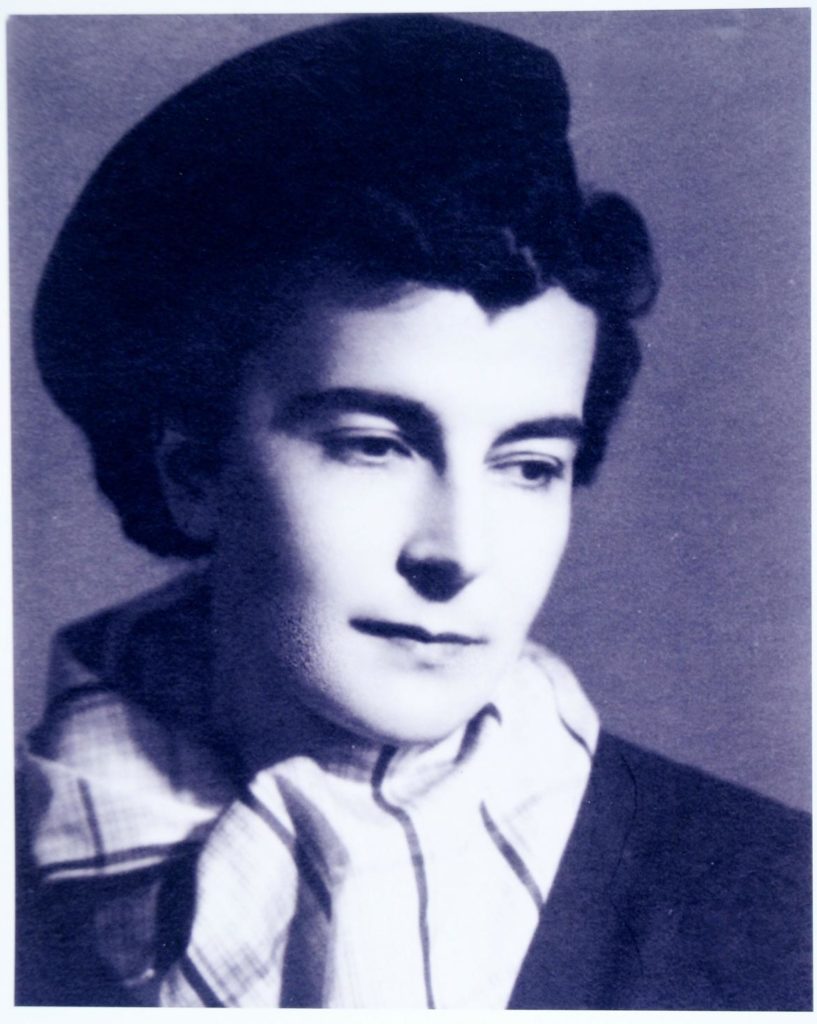

Magdalena Rădulescu (1902- 1983) is a singular phenomenon among the Romanian and European painters. Her work (she had an artistic career spanning half a century) has, of course, common traits with that of other contemporary painters, but cannot be fully inscribed in a specific style or artistic movement. She didn’t have “masters,” she didn’t simply pursue the line of tradition, but neither sought, on the other hand, to appear original at any cost.

Her work, the result of intense, all-consuming feelings and states of mind, can be said to encapsulate an unusual compositional rhythm— an atmosphere essentially Romanian, which can be traced back to folk tales and myths. She was described as a strange being, with idiosyncratic tendencies, constantly on the move, living from day to day; for some critics, she was the incarnation of the troubadours from the Middle Ages.

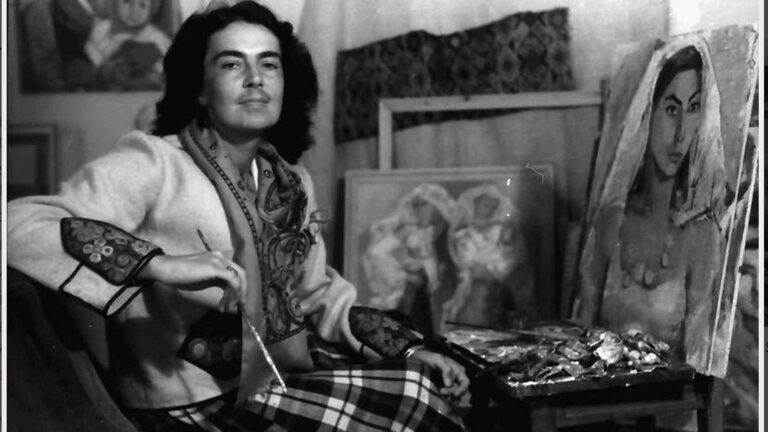

At 18, she left Romania and went to München. Later on, while studying in Paris, she met her future husband, Massimo Campigli. The Romanian author Cella Serghi wrote about Magdalena and their friendship in one of her books. Rădulescu convinced Campigli to give up journalism and pushed him to start painting. When he started making a name for himself, she became the typical housewife and late at night, after a full day of cooking and cleaning, she would start working on a painting which inevitably remained unfinished. Finally, she got a divorce because she wanted to be a painter, not “Campigli’s wife.”

She was considered to be, since Tonitza, the most impressive figure that the Romanian painting scene succeeded in offering. One day, more than 100 of her paintings were destroyed by a bomb which set one of her friend’s house on fire. Serghi described how passers-by were simply walking over Magdalena’s legendary horses, the ones she loved so much, those which she spent her nights drawing.

In 1957, she organized an exhibition in Bucharest, much admired by the Romanian public. The critic Petru Comarnescu would go ahead and compare her lifestyle with that of Gauguin, and the resemblance is indeed noticeable. Gauguin sought to reproduce, through painting, the power of imagination beyond rational censorship; he sought a return to the original instinct of the artist. Disappointed because his search was not fruitful, he left Europe and moved to Tahiti, where he found what he was looking for.

Through the paintings made in Tahiti, he interacted with the whole history of Europe. He tried to define painting, the relation of painting with what life, man, ‘’otherness’’ means. (For Gauguin, these instincts were the equivalent of what Aby Warburg defined as the ‘’Survival’’ of images and motifs). Thus, if Gauguin took refuge in Tahiti, Magdalena Rădulescu surprisingly gave up Paris and withdrew to southern France, exactly at a time when her name and works began to circulate, to be requested in the Parisian art world.

She arrived in Nice with ten paintings and very little money and a Romanian gardener offered her his garden so she can draw. She remembered that from that garden she could see the Coconato Castle, which was inhabited only by guards. She was offered a room in the castle—a room with nothing but a huge mirror. Magdalena recalled that

“At night, in order to have some light (at that time I was working at night as well, I was working a lot), I sat on the floor with twelve burning candles. I lived there for a year and a half. I finished, I believe, hundreds of paintings, with which we opened an exhibition at the Muratore Gallery in Nice, then at Vence. While I was living there, I brought to life all the images and dreams left inside of me, which had returned with such a terrible acuity and force.’’

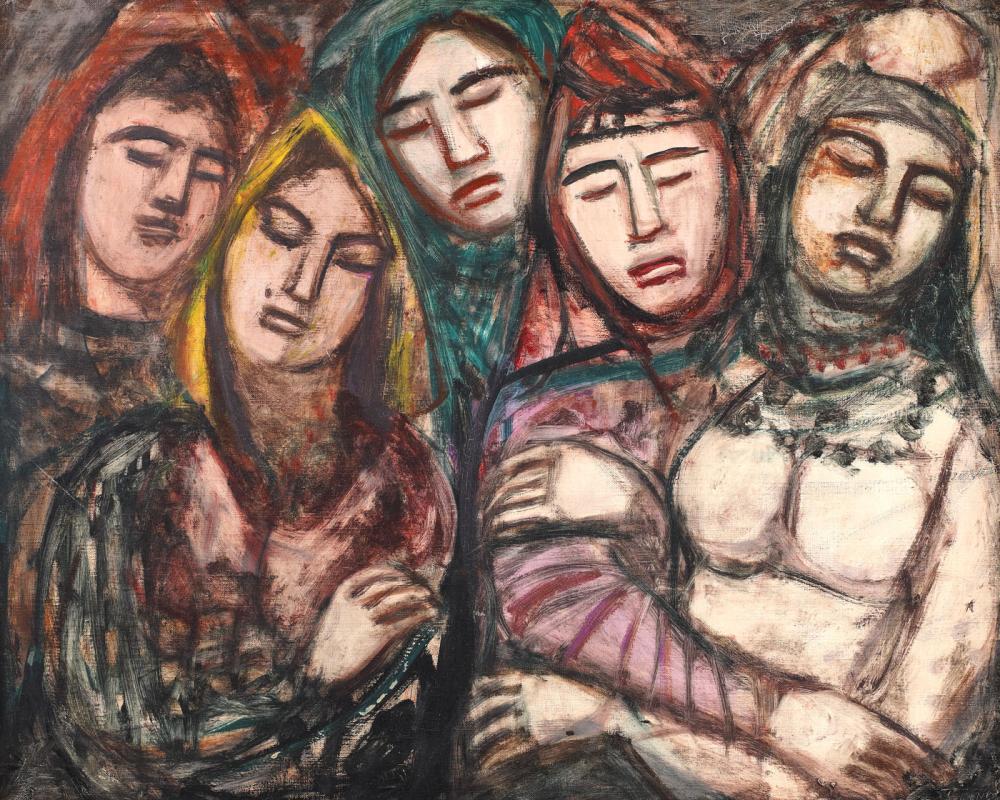

In that way, she distanced herself not only from reality but also from the quests of other contemporary modern painters. Like Gauguin, the artist sought in her isolation the lost area of creativity. She was concerned with the alteration of the image into a reality with psychic valences. She showed disregard for the bourgeois civilization and its superficiality. She offered autonomy to the line in her paintings and looked for the suggestive, emotional senses of color (exactly how, a few decades before, Van Gogh had come up with and developed the concept of suggestive or expressive color, in his search for vision).

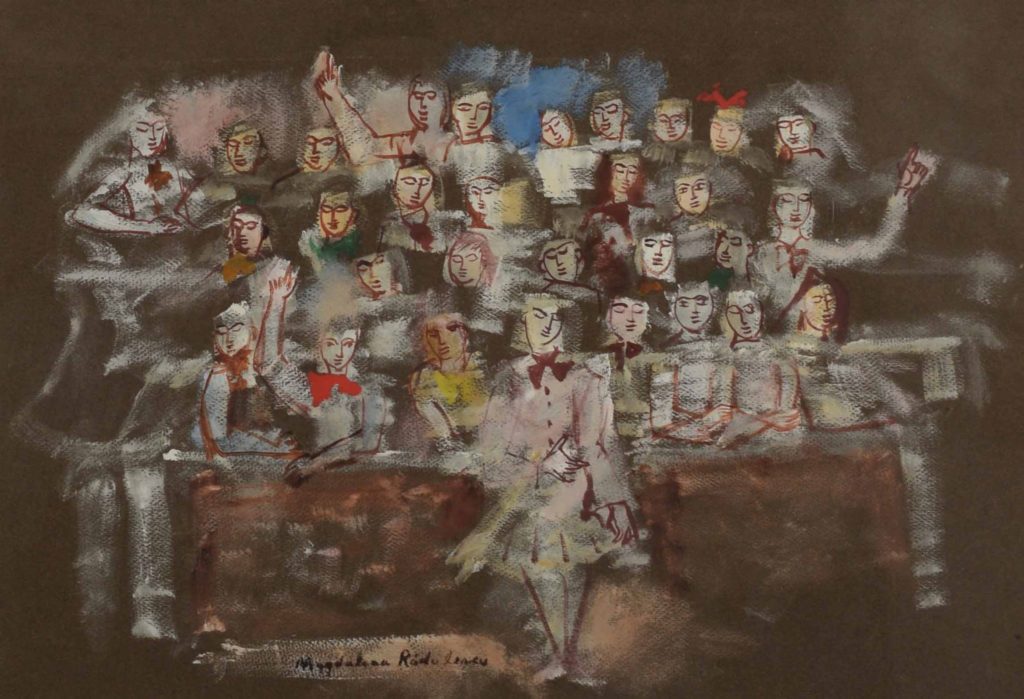

Magdalena was constantly drawing. She was attracted, with no desire for theorizing, to the resurrection of ancient, cosmogonic myths about life and death, about the reconciliation of life with art. Her paintings represent a return to essential harmonies, to symbolic masks, which express, above all, a fascinating, accelerated inner rhythm with human figures often reminding us of the Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in One Thousand and One Nights.

She continued working tirelessly for exhibitions abroad in Monaco, Milan, and Paris (the last two in 1965). Around this time, the novelty when it comes to her works is the inclusion of the ’’Grattage’’ surrealist technique. After these well-received events, she was ready for a new exhibition in Bucharest, in 1970, when she presented 160 works.

What was new? Her paintings showed, perhaps even more than before, an avid interest for movement—a dramatic one,—along with an interest in colors and subtle nuances of rhythm. The preferred themes remained the dances and cavalcades. She found meaning in painting, however, a state of sadness began engulfing her. In June 1971, she learned of Campigli’s death. Then, health issues persisted. But, in this continuous battle, Magdalena still found resources within herself to start new paintings; she put on her canvas, in the most sincere and spontaneous manner, her racing thoughts and nightmares.

Isolation, the intensity with which she experienced the act of creation, her dialogue with the universe brought her closer to the other great painters of that time. But Magdalena’s painting belongs to her. The artistic movements of her time touched her work, but it does not belong to any of them. Dealing with a troubled existence, she found her source of joy in art. Perhaps that is why her work proposes human beings who are glad they are alive, who find their joys like children do, or make them up in their heads, careless of the worries of adults. Maybe her resemblance to Gaugain is the most evident here, because, as he wrote, ’’Me drifting apart from others does not matter, sooner or later, what is good reaches its rightful place.’’

While Virginia Woolf had advocated in her essay A Room of One’s Own for both a literal and figurative space for female writers, Magdalena Rădulescu said that all she needed was a space, no matter how tiny and modest, so she could paint. Her paintings are magnetic, they speak to people after so many years; with each pair of eyes that is fascinated by the dancers, the horses, the colors, Magdalena’s spirit and lesson carries on, and this is the true testament to the importance of this female artist who struggled all her life, but dedicated her existence to art and to sharing that ’essentially Romanian atmosphere’ with the world.

Andra-Maria Velișcu

Andra-Maria Velișcu is 21, graduated from Babeș-Bolyai University’s Faculty of Letters, with a double major in Spanish and English. She’s in love with the sea. Most of the time you can find her reading something, and she’s always on the run.