Life of Malva Schalek

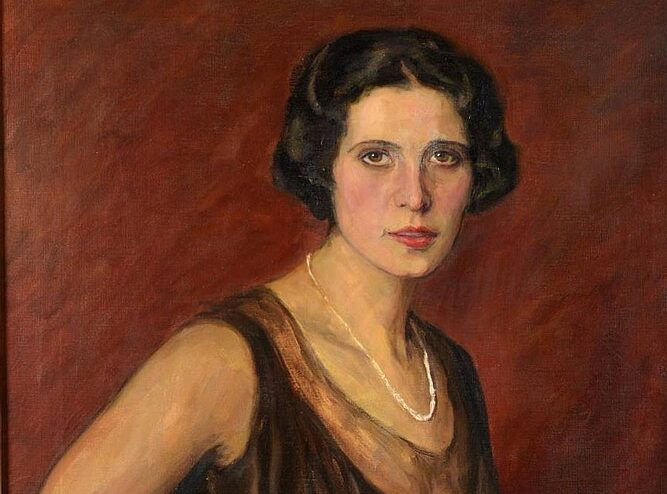

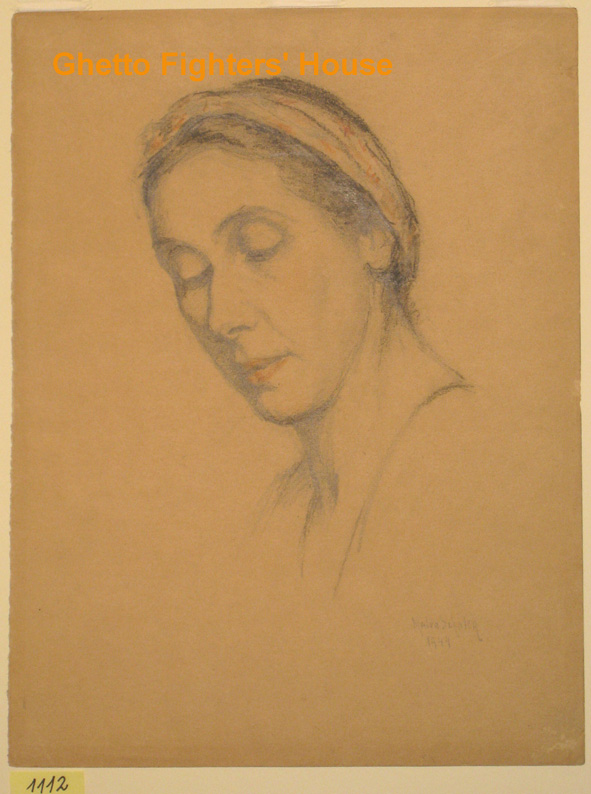

Born to a bourgeois Jewish family in Prague in 1882, Malva Schalek’s journey unfolded against the backdrop of a society in transition. Initially educated at the Girls’ School in Prague, she ventured to Berlin and Vienna to carve her path in the realm of art. It was in Vienna that she found a home for her artistic ambitions, establishing a studio that bore witness to her evolving talent. This phase of her career revealed a particular penchant for portraiture, a genre in which Schalek demonstrated mastery. Regrettably, only a small number of artworks from this period have endured the ravages of time.

The shadow of Nazi annexation loomed large over Austria in 1938, compelling Schalek to abandon her art studio in Vienna and seek refuge elsewhere. The unfolding tragedy of World War II confronted her with an increasingly limited array of choices, culminating in her imprisonment in the Theresienstadt (Terezín) concentration camp in 1942.

Portraiture

Malva Schalek demonstrated exceptional prowess in the realm of portrait art. Her distinctive focus often centered on women and children belonging to the Jewish bourgeoisie. Examining her portraits reveals a nuanced sensitivity toward her subjects, likely stemming from her shared social and ethnic background.

Furthermore, Schalek’s talent found widespread acclaim. Her portraits were not only featured in the Viennese Secession exhibition but also in solo exhibitions, underscoring the recognition she garnered in the art world. Her career came to an end after the outbreak of World War II, and from 1942 to 1944 she was imprisoned at Theresienstadt.

A Monograph of Theresienstadt

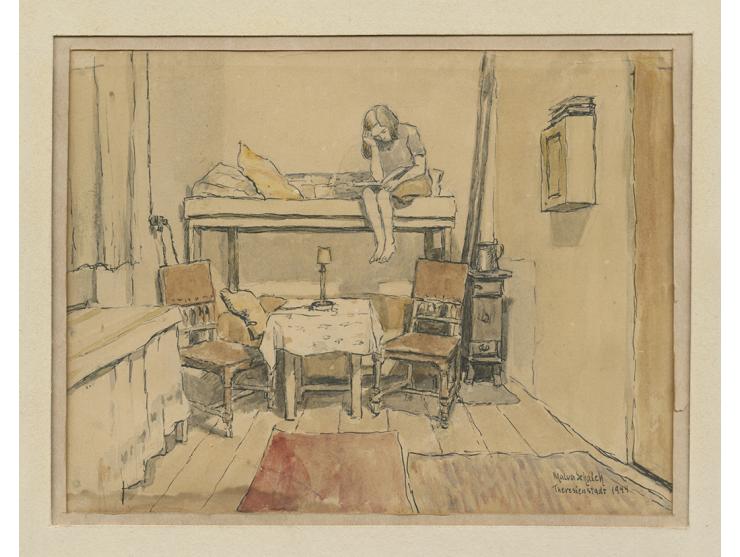

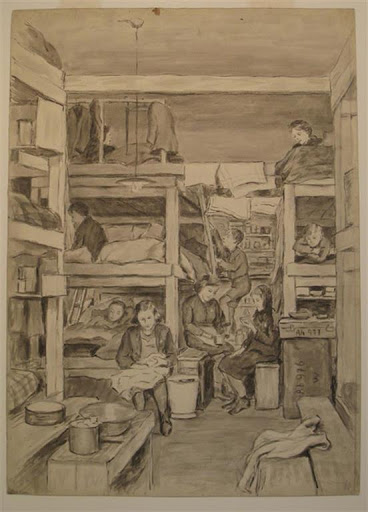

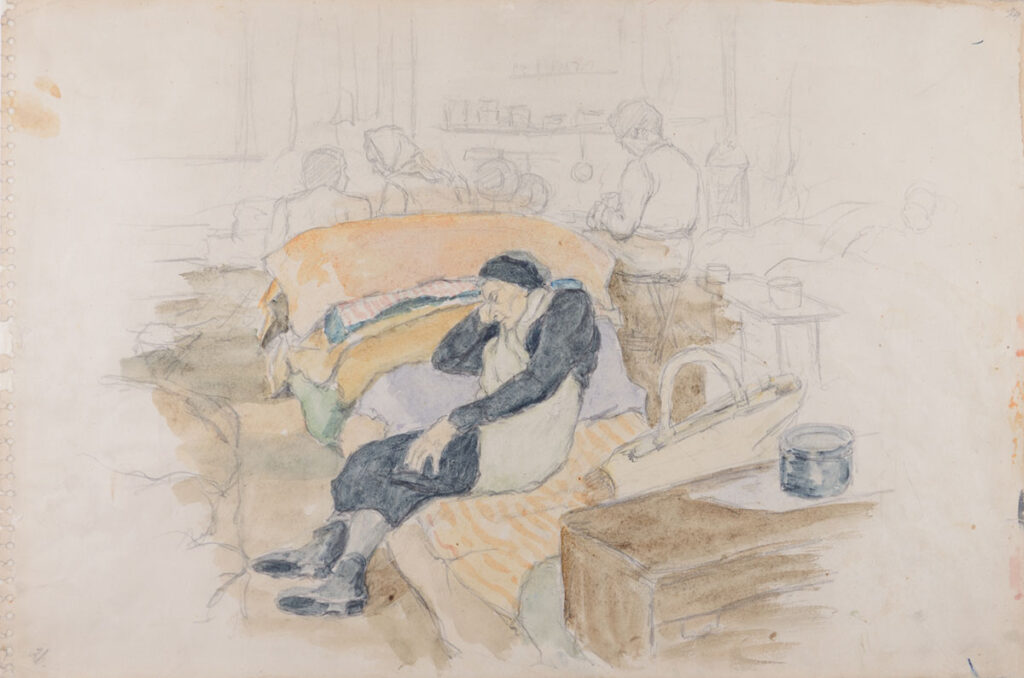

After being imprisoned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp, Malva Schalek’s status as an artist provided her with a measure of immunity among her fellow prisoners. She remained imprisoned there from 1942 to 1944. Theresienstadt marked a profound transformation in her artistic approach. Amidst the challenges of that harrowing time, art became a therapeutic outlet for her.

While she continued sketching portraits of her fellow inmates, Schalek also depicted aspects of camp life, crafting a poignant visual chronicle. Despite the ostensibly domestic scenes portrayed in her paintings from that period, one can feel the alienation and lifelessness pervading them. Through her drawings and watercolors, the artist masterfully captured the oppressive atmosphere of the camp. The crowded spaces, bunk beds, scattered personal belongings, and cramped rooms evoke an unsettling feeling of claustrophobia.