Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

31 March 2024 min Read

Judith Leyster was a powerhouse female artist of the Dutch Golden Age. Man Offering Money to a Young Woman is one of her many masterpieces.

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands.

Judith Leyster (1609-1660) was a leading female painter during the Dutch Golden Age. She achieved fame in both Haarlem and Amsterdam alongside her male contemporaries such as Frans Hals, Johannes Vermeer, and Rembrandt. By 1633, Leyster was the only female member of the prestigious Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke and, by 1635, Leyster was the only woman in Haarlem to own her own artist’s studio where she instructed three male students. Leyster’s work, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, is a masterpiece from this productive period. It is an excellent example of Leyster’s artistic skill and masterful reputation.

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

Judith Leyster painted Man Offering Money to a Young Woman in 1631. It has a small composition that measures only 30.8 cm high by 24.2 cm wide (12.1 inches high by 9.5 inches wide). The image consists of oil paint on a wood panel which was a very common medium during the 17th century. The painting is a genre scene (everyday life) that captures a contemporary moment of an older man trying to seduce a younger woman with the promise of money. We are witnessing an unapologetic proposition of prostitution.

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

The man wears a Moffe-mut (Hun’s hat) which is a symbol of untrustworthiness, and it implies he is an unsavory character. The implication is appropriate because he is soliciting sex for money. He leers over the woman with his left hand holding money as an enticement. His right-hand caresses the woman’s shoulder with uninvited boldness. The woman ignores his advances. She is chaste, and she is virtuously dressed in the blue-and-white color scheme of the Virgin Mary. She focuses on her sewing or embroidery. Her needlework expresses her diligence, productivity, and modesty.

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

The scene explores the theme of unequal love which was a popular subject in the Dutch Golden Age. The dynamics of opposites can produce interesting interactions and comparisons between the figures. Some examples highlighted in this painting are virtue and vice, maturity and youth, active and passive, immodesty and modesty, and male and female.

The contrast of nuanced details can express dramatic realism. For example, the man’s rough hand holds shiny money while the woman’s soft hand holds matte cloth. His life is rough and loud while her life is soft and quiet. The concept of unequal love was a moralistic warning but a sensual delight. Hence, its popularity with 17th-century artists and patrons, and modern art connoisseurs.

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

Judith Leyster had a remarkable ingenuity in exploring the idea of unequal love because it was an unconventional idea in 1631. The motif did not gain widespread adoption until two decades later in the 1650s. Therefore, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman was groundbreaking, and it laid the foundation for later artists who frequently explored the topic. Notable famous artists include Gabriël Metsu, Gerard ter Borch, and Johannes Vermeer. It was Leyster, a female artist, who established a cornerstone theme of Western art. Where is her larger recognition in our collective art history?

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

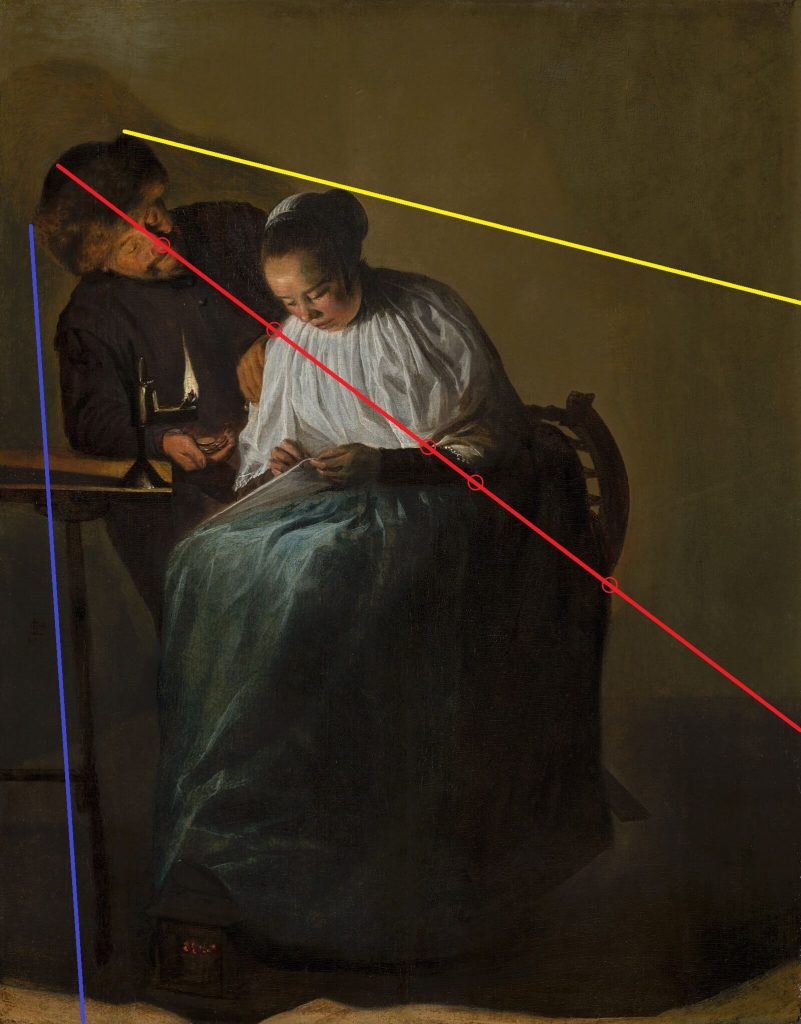

Man Offering Money to a Young Woman has a strong arrangement with its off-centered composition. Two figures dominate the panel’s left two-thirds while empty space dominates the right one-third. An overlay of three equal columns highlights the compositional imbalance. The lecherous old man fills the left red column. The virtuous young woman fills the central yellow column. The shadowy background fills the right blue column. Therefore, positive space fills the left and central columns while negative space fills the right column. The gravitational weight creates visual and compositional interest.

However, some art historians argue the composition was originally balanced by suggesting the panel was cropped after its creation. They assert the surviving panel shows woodworm damage on its left edge, and a later owner cut and removed a left portion of the panel. Therefore, the compositional disharmony may have been intentional or may have been consequential. Regardless, it adds to the painting’s visual strength.

Compositional Overlays. Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands.

Judith Leyster was a master of visual arrangement. She punctuates Man Offering Money to a Young Woman with diagonal visual lines that add movement to the immobile scene. The lines are too accurate and too intentionally placed to be coincidental.

An overlay of three lines highlights the compositional movement. A central red line forms the spine of the sweeping direction. It starts from the top of the man’s Moffe-mut (Hun’s hat), follows the line of his nose, intersects the point where his hand touches the woman’s shoulder, passes the hem of her neckerchief, and intersects the point where the woman’s chair and dress meet.

These five elements align to direct the viewer’s gaze from the top left to the bottom right. A higher yellow line forms the ceiling of the figures. It begins from the man’s hat and skims the woman’s head covering. It too directs the viewer’s gaze. A lower blue line forms the left boundary of the composition. It begins from the man’s hat, skims the man’s shoulder, follows parallel to the man’s forearm, continues parallel to the table’s leg, and ends by the woman’s charcoal foot warmer.

Compositional Overlays. Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands.

The dynamic lines of the painting emphasize the painting’s chiaroscuro. The technique of chiaroscuro is the use of strong contrasts between lightness and darkness. Vibrant light contrasts with the deepest shadow. The candle’s illumination reveals the man’s aroused face and the woman’s serene face. The woman’s chest shines like a beacon of virtue while the man’s fur hat shimmers like a beacon of villainy. In direct contrast are the woman’s skirt and chair. They are shrouded in dark umbra where their forms are barely visible. Are we viewing a nocturnal scene or a dimly lit interior? There is drama, mystery, and intrigue. Hence, the popularity and appreciation of chiaroscuro.

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

Judith Leyster deserves a wider audience beyond feminist art historians and a small niche public. She was a masterful female artist with talent, bravery, and personality. She not only studied under Frans Hals, and surpassed him in some ways, but she also later successfully sued Hals when he stole one of her students. Her paintings frequently include serenity and beauty, but also foreboding and mystery. They are precise but spontaneous. They use refined details and sensitive psychology.

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

Leyster is beginning her ascent to a wider public. Her work and the works of two other female artists, Gesina ter Borch and Rachel Ruysch, are now displayed (since March 2021) in the prestigious Gallery of Honor inside the Rijksmuseum. It is a crying shame that the Mauritshuis in The Hague, Netherlands does not have Leyster’s Man Offering Money to a Young Woman on display!

When will women artists receive their fair share of museum wall space? When will women artists like Judith Leyster become household names like Vermeer and Rembrandt? Art is a worldwide human activity. Women are approximately 50% of the world’s population. Why aren’t museums 50% filled with women’s art? Do women artists need a Hollywood blockbuster film to propel them into the public’s imagination? What will it take? How long will it take? Why wait?

Judith Leyster, Man Offering Money to a Young Woman, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

“Man Offering Money to a Young Woman.” Collection. Mauritshuis. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

“Rijksmuseum Presents Women Artists in the Gallery of Honour for the First Time.” Press Releases. Rijksmuseum, 8 March 2021.

Vigué, Jordi. Great Women Masters of Art. New York, NY: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2003.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!