Summary

- Édouard Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass confronts the artistic tradition of the Old Masters, like Titian, with a modern, Realist style.

- Using the scale of a history painting, Manet presents a scene with the members of the working class, who include naked women. Set among the unidealized landscape, it differs from similar paintings of Realism.

- The painting is one of many of Manet’s depictions of modern Parisian life, yet it also breaks every convention (including the setting of the scene and the clothing).

- The work’s initial title was The Bath, which is more traditional, yet more provocative as outdoor bathing was segregated at the time.

- The Luncheon was rejected from the Salon and instead shown at the Salon des Refusés, where it was one of the most discussed works.

- In The Luncheon and Olympia, Manet was pushing a Realist agenda by the boundaries of traditional art. Apart from those two paintings, however, he rarely attempted to court controversy.

- With this painting, Manet became a figurehead for young artists and those that came after. The work remains an inspiration for today’s art and pop culture.

Édouard Manet, Boy with a Sword, 1861, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Manet’s Luncheon and the Old Masters

Édouard Manet (1832-1883) trained with the academic painter Thomas Couture. He traveled to Italy, France and Germany studying the works of Old Masters like Titian. His early paintings, like Boy with a Sword were often single figures against plain backgrounds, sometimes in costume, like those of Diego Velazquez and Frans Hals. He also painted traditional religious subjects like Dead Christ with Angels (1864).

Although The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe) is a larger, multi-figured canvas, it too shows Manet’s interest in the art of the past. Titian’s Le Concert Champêtre is a sixteenth-century version of a similar subject: two male figures in contemporary dress are sat in a wooded landscape with two female nudes. Furthermore, Manet took the pose of the central figures in his painting directly from the group on the right of a print of Raphael’s Judgment of Paris (c. 1515).

Titian, Le Concert Champêtre, c. 1509, Louvre, Paris, France.

On one level, therefore, Manet is simply engaging with artistic tradition and measuring himself against the painters of the past. As his friend and supporter, the writer Emile Zola, pointed out: This nude woman has scandalized the public (…), in the Louvre there are more than fifty paintings (…) of persons clothed and nude. But no one goes to the Louvre to be scandalized.

However, the style of The Luncheon is far removed from that of Titian. The soft modeling, rich colors and idealized landscape of the Italian work emphasize that the scene is art, not life. Like Kehinde Wiley or Sylvia Sleigh today, Manet seems to be creating a commentary or parody which deliberately challenges the artistic conventions of the Old Masters.

Marcantonio Raimondi (after Raphael) Judgement of Paris, (c. 1515, engraving), Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany.

The Luncheon and Realism

In the 1850s, French art had been rocked by Realism, a movement centered around the art of Gustave Courbet, which aimed to show the grim realities of contemporary life. Realist painters showed poor, working-class subjects on the large scale normally reserved for history painting, and did so with a grimy palette and rough technique which challenged academic ideas of beauty, perfection and finish.

Manet’s Luncheon is on the scale of a history painting (208 by 264.5 cm), but the female figures are not idealized nymphs or goddesses. The main figure’s flesh is pallid, lit by harsh studio lighting, heavily outlined and painted with dark shadows instead of soft shading. She is naked rather than nude—you can see the pile of clothes she has just taken off. No respectable women would undress in public: the implication is perhaps that these are prostitutes.

Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe), c. 1863, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK.

The treatment of the landscape, too, is very unidealized. There is no naturalistic light source, the foliage is coarsely painted, the greens cold. Manet seems to be deliberately ignoring the established rules of recession and perspective. Instead, he creates a series of flat plains, like scenery in a stage setting.

There is a preliminary sketch for The Luncheon, now in the Courtauld Gallery, which suggests Manet deliberately exploited a more Realist style in the finished version. The seated female figure’s auburn hair creates a central, light focus. The background is airier and the foreground shadows darker, giving a greater sense of recession. The male figures’ hands are closer suggesting an interaction which is lacking in the final painting.

Gustave Courbet, The Young Ladies on the Bank of the Seine, 1856, Musée du Petit Palais, Paris, France.

Most Realist works showed rural, lower-class scenes which were completely divorced from the lives and experience of Parisian exhibition goers. When Courbet shifted to an urban subject, Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine, which he successfully exhibited at the 1857 Salon, he toned down his trade-mark ugliness. The water is a rich blue, the foreground dotted with pattern and floral details.

Courbet’s painting is often compared with The Luncheon on the Grass. These women are lounging inelegantly with their legs splayed, one has removed her bodice and the implication is that the “young ladies” of the title is ironic. Manet seems to have directly referenced details like the boat and the clothing on the right. However, whilst Courbet takes a difficult subject and represents it in an acceptable style, Manet makes no concessions to the social and artistic conservatism of his audience.

Édouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries, 1862, National Gallery, London, UK, currently displayed at Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, Ireland.

Manet’s Luncheon and Modern Life

In 1863 Charles Baudelaire wrote an essay calling for art to embrace modern, urban life and find a new transient and sketchy technique to represent the fast moving crowds of the city. Manet himself had painted a large-scale modern subject the previous year. Music in the Tuileries shows a gathering of middle-class Parisians, many of them recognizable as his friends, at an outdoor concert. The broad brushwork and deliberate lack of focus creates a sense that we are part of the crowd catching a glimpse of this scene full of movement and sound.

The Luncheon on the Grass has a similar wooded setting, perhaps the Bois de Boulogne or l’Île Saint-Ouen, both areas of green space used by Parisians for leisure. Again, the models were people Manet knew. Equally, the loose brushwork is repeated in The Luncheon and there is the same sense of flattened space and lack of traditional perspective. The figure that catches our eye on both works is a woman staring out of the canvas.

The male figures in The Luncheon are clearly dressed in the height of fashion, perhaps dandies or students. But whereas Music in the Tuileries shows an acceptable social gathering, these men are having a picnic in a secluded corner with women of a dubious reputation. Tellingly, instead of a bottle of wine, the picnic includes a metallic flask of stronger spirits, and the male figure on the right is sporting the sort of cap he would normally wear indoors. Every sort of convention is being broken. This may be a subject from modern life but it is not one men and their wives would want to be faced with in a gallery.

Gustave Courbet, Les Baigneuses, 1853, Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France.

The Original Title

The first title of Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass was Le Bain (The Bath), more traditional, but also more provocative. Bathing scenes were common in academic art: nymphs, Turkish baths and myths like that of Diana surprised by Actaeon but this was definitely not what Manet was representing. Segregated outdoor bathing was common at the time, but these women are so liberated, or so lacking in decency, that they were prepared to bathe in front of men.

Courbet had successfully submitted a painting called Les Baigneuses (The Bathers) to the 1853 Salon. It too controversially showed contemporary women who had discarded their clothes to bathe outside. Like Manet’s work, these women were unidealized, with their awkward poses and heavily shadowed flesh. Like Manet’s, it was on a large scale. However, a lack of male figures, careful posing and drapery allowed just enough ambiguity for the Salon jury to accept Courbet’s version.

Édouard Manet, Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada, 1862, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

How Was The Luncheon on the Grass Received?

The 1863 Salon jury rejected The Luncheon on the Grass and in a normal year it may well not have been exhibited at all. But this time so many works were rejected—around two-thirds of all those submitted—that Napoleon III decided to hold an alternative Salon des Refusés (Exhibition of Refused Works). It was here The Luncheon was shown, along with two more of Manet’s paintings (including Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada).

The Salon des Refusés proved to be far more popular that the official Salon. On opening day, 7000 people flocked to see pictures considered scandalous, ugly, and outrageous. And Manet’s Luncheon was one of the works which attracted most attention. Critics like Ernest-Alfred Chesneau objected to the style: Its garish coloring pierces the eyes like a steel saw; his figures seem to have been cut out with a punch. Others attacked the figures as ugly and out of place. Most people, however, like writer Théodore Pelloquet, simply found the painting incomprehensible: M. Manet doesn’t know how to compose a tableau…I wish he had helped me understand his intention.

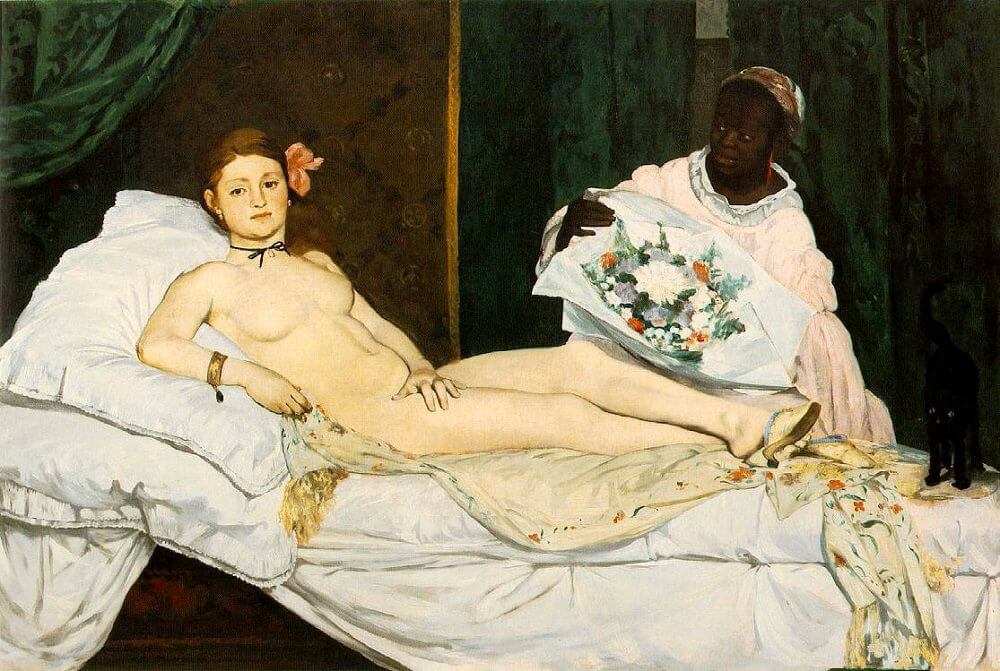

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France.

The Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia

Was Manet being deliberately controversial with The Luncheon on the Grass? In 1865 he exhibited Olympia, another work which updated a traditional subject—the reclining female nude—to a contemporary setting. Olympia was accepted for Salon exhibition but was, if anything, more controversial than The Luncheon. It features the same model, Victorine Meurent, again looking directly out of the canvas with enough contemporary references, like the slippers, shawl and ribbon, to place her firmly in the real world. Taken together with The Luncheon, it seems to both reinforce the narrative that these were sex workers, and the idea that Manet was deliberately pushing a realist agenda by the boundaries of traditionally acceptable art.

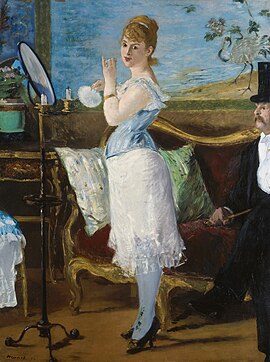

Édouard Manet, Nana, 1877, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany.

However, Manet was not a natural radical. His other 1863 paintings, like Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada, are a balance between tradition and innovation. Manet never contributed to the breakaway Impressionist exhibitions, despite being friends with many members of the group. His later works seem far less controversial. He rarely painted nudes during the rest of his career. Nana (1877) also depicts a prostitute—the name was commonly associated with the profession and was later similarly used by Zola in his 1880 novel—and we can see her client in the corner of the canvas. Yet the female figure here is partially clothed, is more conventionally pretty and presented in a feminine, almost rococo palette. She looks towards us, but her gaze is far less confrontational.

Claude Monet, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe), 1865–1866, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

The Legacy of Manet’s Luncheon

The notoriety of Manet’s 1863 painting made him a figurehead for young artists. In 1865 Claude Monet attempted his own version of The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe), intended as a tribute to Manet and a statement of his own artistic priorities. Fashionable Parisians lunch elegantly on a white cloth, in a woodland setting. The huge scale of the canvas, which Monet wanted to paint plein air, meant the work was never finished and today only exists in fragments. However, it was the start of a close friendship between the two men which led to them working together during the 1870s.

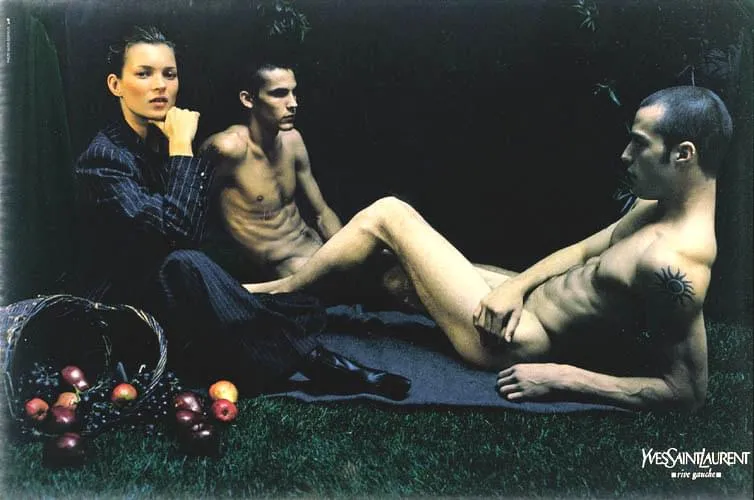

If anything, Manet’s Luncheon became more influential after his death. Picasso produced a series of twenty-seven paintings and over a hundred prints and drawings based on the painting. In 2022 a Los Angeles gallery brought together thirty contemporary artists’ works inspired by The Luncheon on the Grass. Equally, the image continues to be used commercially, from a 1980s punk album cover to Yves St Laurent’ s 1999 image of a clothed Kate Moss with two nude men.

Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe), 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass (Déjeuner sur l’Herbe) has nowadays lost its shock-value. Viewers today are familiar with realistic depictions of nudity and what was seen as a lack of finish in 1863 seems utterly conventional now. But the painting retains its mystery and its strangeness. We still do not know what Manet’s intentions were. We still can only speculate about the four figures and their abandoned picnic. Most significantly, Victorine Meurent’s stare still holds our attention. Defiant, quizzical, ironic and as contemporary now as it was in 1863.

Yves Saint Laurent Ruve Gauche Spring/Summer 1999 campaign with Kate Moss. Photographed by Mario Sorrenti for the Alber Elbaz. Vogue.