Summary

- Maria Sibylla Merian learned art from her stepfather. She demonstrated a fascination with insects and plants since early childhood.

- In 1675, Merian began publishing her illustrations of the plants and insects she kept and raised.

- Merian divorced her husband by the end of the 17th century and moved to Amsterdam, where she grew an interest in the ecology of Dutch colonies. She decided to travel to Suriname to study it, a dream eventually realized in 1699.

- In 1705, Merian published her groundbreaking work, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. The book contains detailed descriptions and illustrations of the tropical species of Suriname.

- Merian’s observations, rendered through texts and pictures, revealed how plants and insects could interact with their ecosystems. They were cited and copied by generations of artists.

Early Life

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) was born in the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt (today’s Frankfurt am Main) within the Holy Roman Empire. She was born as a ninth child into a Frankfurt branch of a Swiss patrician Merian family based in Basel. Her father, Matthäus Merian the Elder, was an engraver and publisher who specialized in town plans and prepared a multi-volume series Topographia Germaniae. Unfortunately, Matthäus Merian died in 1650 in Wiesbaden after years of illness. A year later, Maria Sibylla’s mother married Jacob Marrel, a German-born still-life painter active in Utrecht.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Plate 18 from The Caterpillars’ Marvellous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, An apple blossom, a gypsy moth laying eggs, and caterpillar hatch, 1679. Art Herstory.

As in the case of most early modern female artists, Merian’s artistic education began at home under the tutelage of her stepfather, Jacob Marrel. In the times, when girls were not given easy access to artistic and academic education, the privilege of knowledge was available only to a small circle of women who were fortunate to be born into educated patrician families.

Merian spent her childhood collecting plants and insects and observing the life cycles of caterpillars and silkworms – a process she then drew in remarkable detail. She referred to her early observations in the following words:

I spent my time investigating insects. At the beginning, I started with silkworms in my hometown of Frankfurt. I realized that other caterpillars produced beautiful butterflies or moths, and that silkworms did the same. This led me to collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to see how they changed.

Foreword from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, originally published in 1705.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Daffodil, Scorpion grasses and Butterflies, ca 1657–1659, early drawing Merian made at the age of 10. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

First Publications

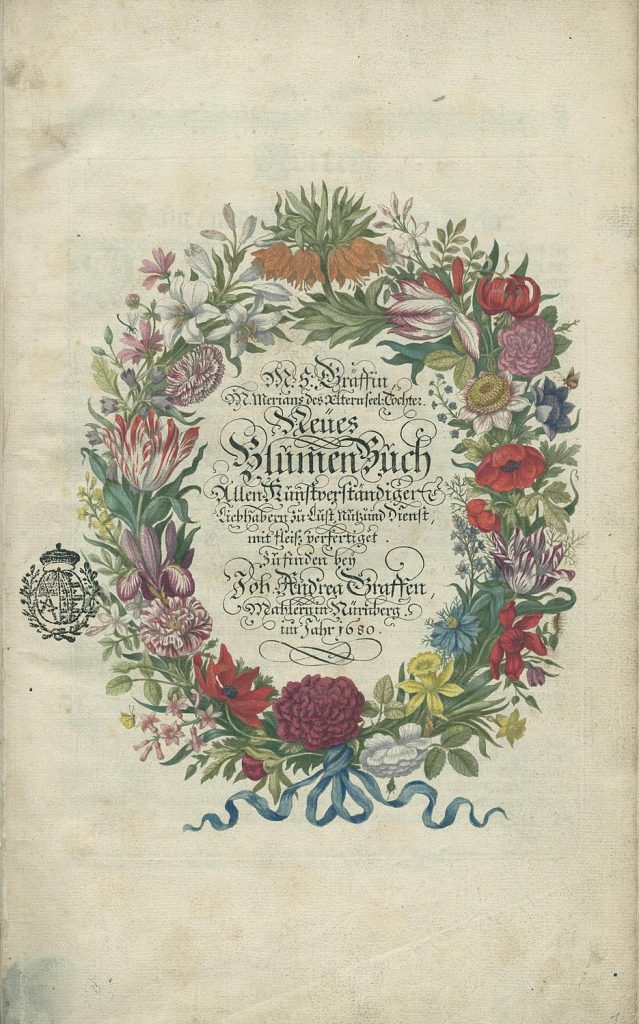

In 1665, Merian married her stepfather’s apprentice, Johann Andreas Graff, and moved to Nuremberg. Merian and Graff had two daughters and lived there for 14 years. During that time, she continued to collect plants and insects she documented in her paintings and engravings. Merian also gave painting lessons to unmarried daughters of wealthy families through which she was granted special access to gardens rich in the finest flora. The illustrations Merian created during her Nuremberg time were published in 1675 in her first book, Book of Flowers (Blumenbuch), which appeared in three volumes and was reprinted with a preface as the New Book of Flowers.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Frontispiece of New Flower Book Vol. 1 (reprint of Book of Flowers, 1675). Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Merian defied convention by being professionally active in the times when a married woman with children should stay home. In 1679, a year after her youngest daughter’s birth, she published her second book, Caterpillars, Their Wondrous Transformation and Peculiar Nourishment from Flowers (Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung, und sonderbare Blumen-nahrung). This time, the publication was about insects where she described and depicted in her illustrations the metamorphosis of moths and butterflies. This was one of the first such publications revolutionizing our perception of insects and introducing a new standard for scientific illustrations. While her contemporaries also depicted insects in their botanical illustrations, Merian was the first artist to study and breed them.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Plate I of Caterpillars Volume l 1, Maulbeerbaum samt Frucht, Fruit and leaves of a mulberry tree and the eggs and larvae of the silkworm moth. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Below, you can see a portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian painted by her stepfather, Jacob Marrel, in the year of her second publication (1679). We can see her depicted as a wealthy woman wearing an elegant black dress with a refined white ruff covering her shoulders and decolletage.

Jacob Marrel, Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian, 1679, Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

Amsterdam

A marriage between Merian and Graff was an unhappy one, so she decided to take her daughters and move to Amsterdam in 1691. A year later, she divorced her husband. This was a new beginning for her and her career.

Amsterdam, in the 17th century, was a European capital of culture, science, and trade. Merian networked with the most prominent scientists and collectors. She also took students and among them was Rachel Ruysch, one of the best Dutch still-life painters (in her lifetime, her works fetched higher prices than those of Rembrandt!). Since Amsterdam was also one of Europe’s major commercial hubs, it experienced a massive influx of wealth, luxury commodities, and exotica from all around the world. Trading ships brought never seen before shells, fossils, featherwork, preserved animals, and tropical plants that were sought after by art connoisseurs. When Merian encountered them, she was not interested in merely collecting them in a preserved form, but she wanted to study them in their natural environment.

In these collections I had found innumerable other insects, but found that their origin and their reproduction is unknown, it begs the question as to how they transform, starting from caterpillars and chrysalises and so on. All this has, at the same time, led me to undertake a long-dreamed-of journey to Suriname.

Foreword from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium.

Balthasar van der Ast, Still Life with Shells, ca. 1640, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Suriname

Planning a transatlantic journey in the 17th century was not an easy thing, especially for a woman. Merian already had existing contacts connecting her to the Dutch trading companies and among them were Nicolaes Witsen, president of the Dutch East India Company, and her son-in-law, Jakob Hendrik Herolt, a merchant in Suriname trade who was married to her first daughter, Johanna. In order to undertake this journey and finance it, Merian sold all of her flower paintings to prominent art collectors such as Agnes Block.

In 1699, Merian was granted permission to travel to Suriname from the city of Amsterdam. On July 10, 1699, she set sail for this long and dangerous journey with her youngest daughter Dorothea Maria and arrived on September 18 or 19 . They are thought to be the first women to travel in the name of science. Interestingly, the first European painter to depict the landscapes of the Americas came from the Netherlands. Merian was 52 years old and Dorothea Maria was 21 years old at the time of their departure. The goal of their expedition was to spend five years in Suriname observing and documenting tropical plants and insects. As every European newcomer to the Americas, both Merian and her daughter were unaccustomed to the tropical climate and suffered from it while doing their research in the jungle. But the struggle paid off.

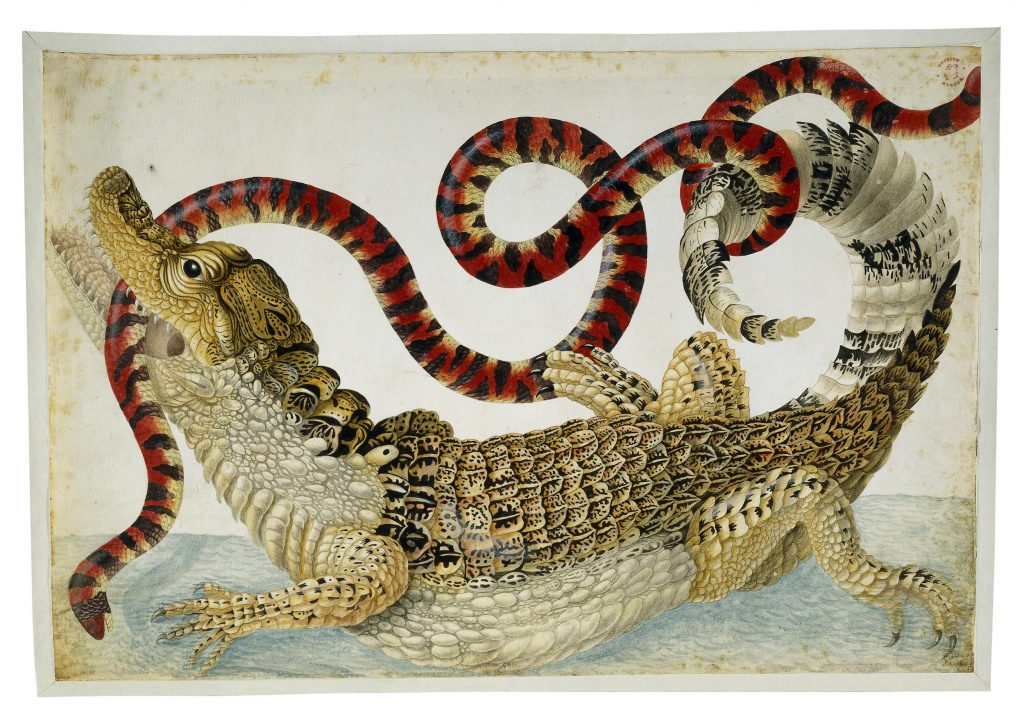

In 1705, Merian published her groundbreaking work, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname), documenting stages of development of Suriname’s caterpillars and stunning butterflies. Also, the book consisted of descriptions and detailed illustrations of tropical animals encountered by her in Suriname. Many surviving works are done by Merian’s daughters, Johanna and Dorothea, who were trained by her and directly copied her drawings.

Innovative Observations

The novelty of Merian’s written and visual observations was revealing the relationship between certain species and their development in their ecosystems. She observed that the metamorphosis from caterpillar to butterfly depended on certain plants and their surroundings. In addition to the habitat of insects, Merian also noted their behavioral patterns and their use to the Indigenous people. But her studies were innovative not only due to their scientific content, Merian also acknowledged and criticized the mistreatment of enslaved Surinamers and Africans, however, she too took advantage of the colonial system. She used the enslaved people to help her catch and breed insects, incorporated their knowledge of local plants and animals, and even took one Indigenous woman with her to Amsterdam to help her with the production of her book (her name, however, was never mentioned).

Although Merian planned to stay longer in Suriname, her sojourn was cut short by illness (possibly malaria) and, in 1701, she returned to Amsterdam.

Jacobus Houbraken after Georg Gsell, Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian, c. 1700, copperplate. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

This is an occupational portrait of Merian where her status of a learned and accomplished woman is suggested by a pile of books, a globe, and prints.

Merian’s Legacy

Maria Sibylla Merian led a very independent life as a woman, artist, and scientist in the 17th century. After her stay in the tropics, she returned to Amsterdam and opened a successful workshop with her daughters which was the main source of the family’s income.

In 1715, she suffered a stroke and died two years later aged 69. In the last two years of her life, Merian was partially paralyzed but continued to work. After her death, her daughters compiled and published a collection of their mother’s work, Erucarum Ortus Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis.

Merian’s works were copied and cited by generations of artists and her descriptions of animals’ struggle for existence predate those of Charles Darwin and Lord Tennyson’s theories. Today, a number of plants, animals, and insects are named after her, and her observations on the biodiversity of Suriname are still valued and show us how some species adapt to climate change.