Beginnings

Marie-Anne Paulze was born in 1758 in Montbrison, France to an aristocratic family. After receiving her formal education in a convent, Paulze married French chemist, nobleman, and tax collector Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794). Shortly after their marriage, Paulze Lavoisier was formally trained in chemistry by one of her husband’s colleagues, Jean-Baptise Bucquet.

Antoine Lavoisier, the first individual to recognize the true natures of oxygen and hydrogen, is credited as being the first male chemist and the father of modern chemistry—but he didn’t act alone. In fact, centuries later, it has become apparent that more than one hand was at work.

Bridging Two Worlds

At the time, some of the most important scientific research was being done in England—this prompted the young Paulze Lavoisier to learn English.

Marie Anne Paulze Lavoisier’s translations of major texts in the field were pivotal in facilitating her husband’s understanding of the theories of Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) and Richard Kirwan (1733-1812) and keeping him abreast of the latest developments. By hosting weekly salons, Paulze Lavoisier led one of the most important scientific circles in Paris, entertaining distinguished guests such as James Watt and Benjamin Franklin.

Working closely together, Antoine and Marie-Anne restructured and modernized the field of chemistry, which at the time was still rooted in alchemy. Perhaps most important of all was Paulze Lavoisier’s translation of Richard Kirwan’s Essay on Phlogiston and the Constitution of Acids (1787), which convinced Lavoisier to discredit the theory, ultimately leading to his discovery of oxygen and hydrogen.

David’s Dual Portrait

A portrait by Jacques-Louis David of the husband-wife team from 1788 features the modern couple in an intertwined pose. A cornerstone of European portraiture, the painting exhibits the duo’s intellectual collaboration while capturing their mutual admiration. Paulze Lavoisier takes center stage, her body mimicking the column behind her as she looks out at the viewer, inviting us to join the conversation. Writing with a quill pen, Antoine Lavoisier looks up at his wife, as if to seek her guidance.

Indeed, so interlaced were the Lavoisiers’ intellectual endeavors that it is often difficult to tell their accomplishments apart. Paulze Lavoisier was her husband’s professional collaborator, lending her scientific, artistic, and linguistic expertise to what would become groundbreaking research in the field of chemistry. David’s portrait evokes this remarkable union of art and science, emphasizing the partnership between husband and wife.

Glass beakers and other instruments are scattered about the scene, showcasing the couple’s scientific research. Thanks to modern infrared reflectography (IRR), which reveals the underlayers of a painting, conservators have been able to identify several major changes made to the portrait by the artist: namely, that a fashionable feathered hat once sat atop Lavoisier’s head as well as the initial exclusion of the scientific apparatuses. It is clear that the Lavoisiers wished to be depicted not as people of wealth, but as people of science.

Lavoisier Paulze the Artist

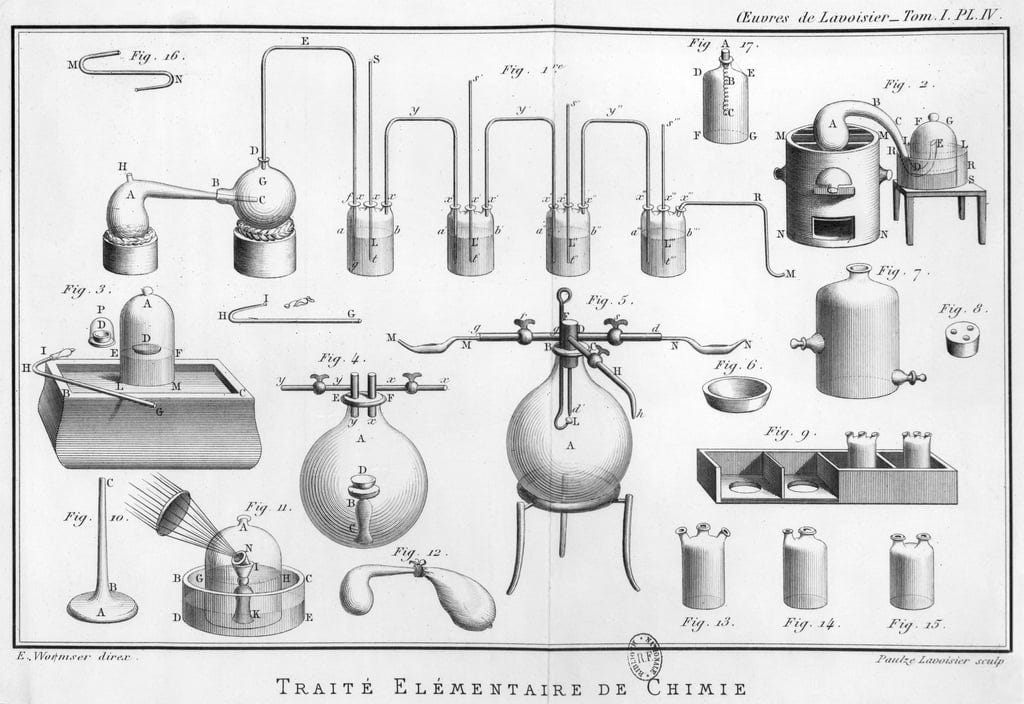

Having learned to paint under the famous French artist Jacques-Louis David himself, Paulze Lavoisier would go on to employ her artistic talent by drawing hundreds of sketches of her husband’s scientific research. Not only did Paulze Lavoisier serve as her husband’s assistant for nearly all of his experiments, which were conducted in their home laboratory, she also drew detailed recreations of his studies, providing the illustrations and engravings for his books. This included the famous Traité élémentaire de chemie (Elementary Treatise on Chemistry) from 1789, which laid the groundwork of modern chemistry.

Part of Antoine Lavoisier’s scientific research involved constructing highly accurate balances and developing new equipment. Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier is credited with making multiple detailed illustrations of these apparatuses.

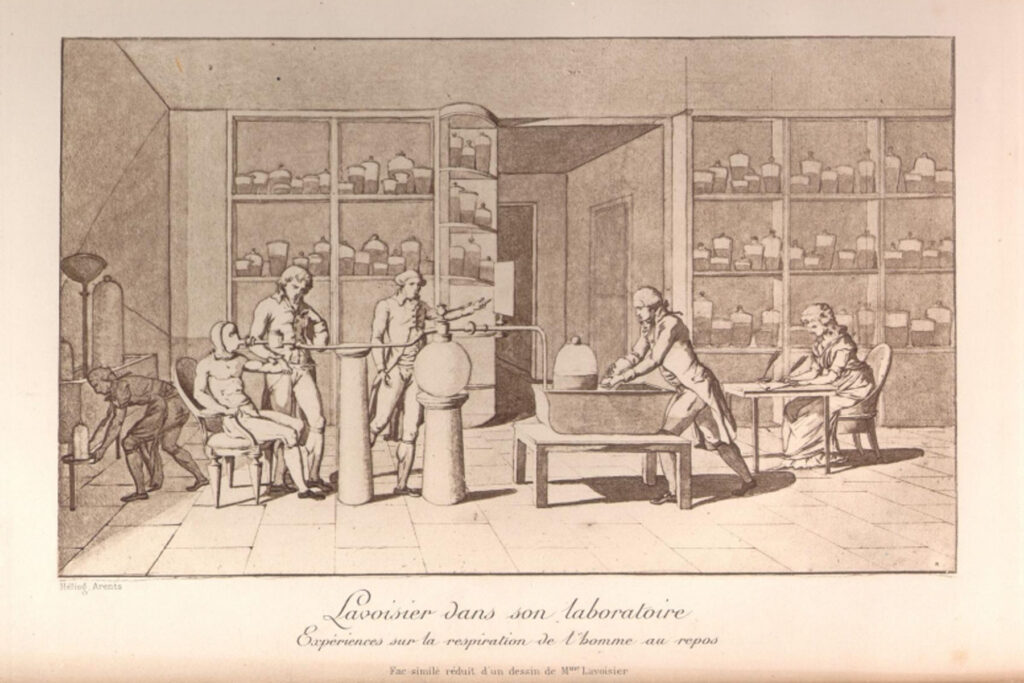

Two drawings in particular illustrate Lavoisier’s important experiments in measuring oxygen consumption. Featured in the far-right corner, diligently taking notes, is none other than Paulze Lavoisier herself. Amidst the turbulent events of the French Revolution, Antoine Lavoisier was so tied up with matters related to his tax organization that he left no written accounts of his work. Paulze Lavoisier’s drawings are the only surviving records of these experiments.

Leaving Her Legacy

In 1794, the Lavoisiers’ tour de force was cut short when Antoine Lavoisier was sent to the guillotine for his activity as a tax collector for the French crown. After his death, the couple’s scientific equipment was confiscated and Paulze Lavoisier quickly disappeared from public consciousness. Today, due to a renewed interest in her indispensable scientific, artistic, and linguistic contributions, she is considered by many to be the mother of modern chemistry. Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier was an invaluable asset in bolstering her husband’s scientific endeavors and securing his legacy—it is now our duty to secure hers.