Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

2 March 2025 min Read

The Venetian Renaissance painter Marietta Robusti has recently caused a stir in the art history world. Although only a few works are attributed to her, her Self-Portrait with Madrigal is exceptionally interesting. Presenting herself as a feminine, modest musician rather than an artist, she entangles many mysteries. Is Marietta Robusti the artist of this self-portrait, or do the primary sources create confusion about her painterly skill?

As a female Venetian painter during the Renaissance, it was impossible to sell your artwork to the public world. Women at this time were expected to remain within their domestic domain of society, in accordance with the patriarchal ideology of separating genders based on one’s proper position in public and private spheres. While this idea is repugnant in today’s society, women back then were expected to take care of housekeeping and focus on personal religious studies.

However, some female painters were able to enter the art world through the involvement of their fathers or brothers. This is how Marietta Robusti, or “la Tintoretta,” profoundly impacted Renaissance art through her painting Self-Portrait with Madrigal.

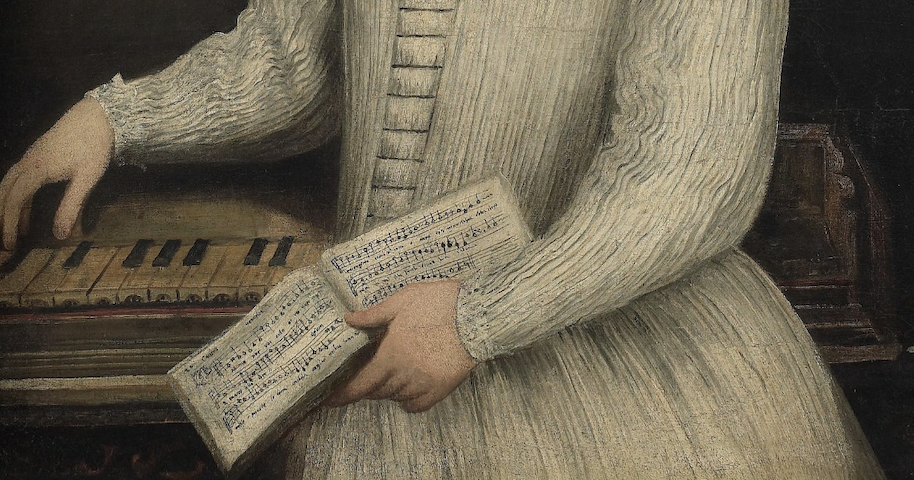

Marietta Robusti, Self Portrait with Madrigal, 1578, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Museum’s website. Detail.

Marietta Robusti was the eldest daughter of the painter Jacopo Robusti (Tintoretto), from whom she inherited her nickname “la Tintoretta.” She was born sometime between 1555 and 1560 in Venice, Italy, where she spent her entire life, and died in 1590. Her life is documented in Life of Tintoretto written by Carlo Ridolfi in 1642. Robusti is also mentioned in Raffaello Borghini’s book, Il Riposo della Pitura e della Scultura, published in 1584, sixteen years after Giorgio Vasari’s famous book, Lives of the Artists. Il Riposo della Pitura e della Scultura is significant in art history because Borghini focused on issues that Vasari excluded. Mentioning Robusti in this work was a testament to her impact on Renaissance art.

However, there are only a few paintings attributed to Marietta Robusti. The most famous is her masterpiece Self-Portrait with Madrigal, currently at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

Marietta Robusti, Self Portrait with Madrigal, 1578, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Museum’s website.

The self-portrait is intriguing because not all art historians believe Marietta Robusti actually painted it, and we won’t be completely sure anytime soon. This portrait is one of only a few paintings attributed to Robusti, making it extremely rare. But what is said about Robusti in contemporary texts after her death creates a peculiarly rare outlook on the female painter. Although the painting is beautiful, the poor foreshortening of the figure does not indicate the artist’s skillful manner as described in texts by her contemporaries and questions the credibility that she painted the Self Portrait with Madrigal.

Carlo Ridolfi’s book best describes Robusti’s relationship with her father, as well as her skill. Since she learned how to paint from him, they had an extremely strong bond. Contributing to her legacy, Ridolfi claims that Robusti was just as talented in painting as her father, saying she displayed “sentimental femininity” and professed determination that was admirably purposeful through her work. Whether Ridolfi was talking about this specific portrait or not, we will never know. But what is noted on the Uffizi Gallery’s website is the connection between music and painting that Robusti maintained.

Marietta Robusti, Self-Portrait with Madrigal, 1578, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Museum’s website. Detail of the music sheet.

Although she was not allowed to be a painter, she was trained in the art of music. Music was a proper and sophisticated skill for a woman to have during the Renaissance. Lavinia Fontana and Sofonisba Anguissola both created self-portraits of themselves playing music.

In Robusti’s self-portrait, music is accurately presented in the foreground. In one hand, her fingers delicately touch the keys of a harpsichord, while in the other hand, she holds a music sheet with the words of the Cantus of the madrigal by Philippe Verdelot. In Italian, it says Madonna per voi ardo, meaning “My lady, for you I burn.” Multiple sources confirm this musical sheet was printed in Venice in 1533. Since the quote is quite direct, some historians speculate that the self-portrait was made for her future husband, because eight years later, in 1586, she married Jacopo Augusta.

Left: Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait at the Spinet, 1561, The Castle Museum in Łańcut, Poland. Right: Lavinia Fontana, Self-Portrait at the Spinet, 1577, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome, Italy. Smithsonian Magazine.

Unfortunately, in her mid-thirties, Robusti died in childbirth. Although her life was short, she impacted the standard of femininity in art for centuries. Romantic painters during the 19th century, such as Léon Cogniet and Eleuterio Pagliano, regarded her as their muse. In 1846, Cogniet painted Tintoretto Painting His Dead Daughter. Then in 1861, Pagliano produced Tintoretto and His Daughter. Both of these paintings showcase Robusti as a muse for male painters by redefining the femininity of women artists.

Regardless of the painting’s precise attribution, Marietta Robusti has definitely impacted Renaissance art and influenced future artists. Currently, most of the evidence points to her as the artist of Self-Potrait with Madrigral, where she professed her femininity, musical skill, and love of painting through the details.

Katherine A. McIver: “Lavinia Fontana’s “Self-Portrait Making Music”.” Woman’s Art Journal 19, no. 1 (1998).

Carlo Ridolfi, and Claudia Ridolfi: The Life of Tintoretto, and of His Children Domenico and Marietta. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1984.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!