Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

The name Marion Mahony Griffin (1871–1961) may not ring any immediate bells for you, but she was responsible for creating the unique look and feel we associate with Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs. It was her renderings of his projects that enticed investors to go ahead with the construction. She was the author of America and Australia’s most distinctive architectural drawings.

* Reyner Banham, “Death and Life of the Prairie School,” Architectural Review 154 (August 1973): 101, quote after Pioneering Women

Photograph of Marion Mahony Griffin. Institute of Classical Architecture & Art.

Mahony was born in 1871 in Chicago, Illinois. In 1880, after the Great Chicago Fire, her family moved to Winnetka. There she had an idyllic childhood in a small community founded by Unitarians. This environment combined the closeness to nature with rich spirituality.

Thanks to the support of Mary Hawes Wilmarth and her daughter Anne, Mahony was able to enroll at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1890. When she graduated from architecture at MIT in 1894, she was the second woman to accomplish that feat. That, of course, was only the beginning; she swiftly proceeded to become the first woman licensed to practice architecture in Illinois. Marion quickly started working for her cousin, Dwight Perkins, at his studio in Steinway Hall. This is also where she must have met Frank Lloyd Wright, who hired her after Perkins had to let her go for financial reasons.

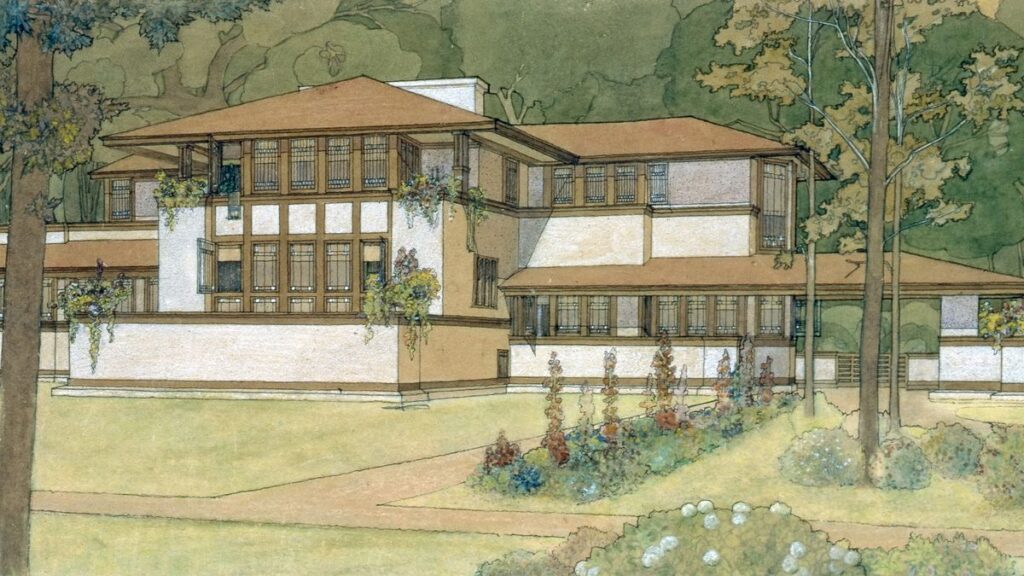

Marion Mahony Griffin, renderer, Ward W. Willits House, 1902, Highland Park, IL, USA. Curbed.

Marion was the first employee in Wright’s studio, and they continued working together for over a decade, as his studio grew and he became more and more famous. Wright valued her and he was aware of her talent to the point where he would claim her work as his. To motivate architects at his studio, Wright often organized internal contests and those were routinely won by Marion. She was an energetic person, who did not give up easily and would fight for her opinions and beliefs. At the same time, she was full of joy, and it is said that her laughter could be heard long before she was seen.

She worked as an architect and designer, but where she left her mark is in the work known as drafter/delineator/renderer. It is a person who creates what we would now call visualizations, translating the technical architectural design into a vision a lot more palpable for the wider public. Then, as now, such visualizations were really what sold the project, so without her work, much of Wright’s success would not be possible.

Marion Mahony Griffin, renderer, Unity Temple, 1905, Oak Park, IL, USA. Curbed.

Marion wholeheartedly embraced the ideals of Prairie School, an architectural movement inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, but also aimed to create a uniquely North American style, free from traditional European influences, and instead more in tune with the local spirit, nature, and environment.

When Wright left for Europe in 1909, he first offered Marion Mahony Griffin to take over his studio, but she declined. Nonetheless, she ended up working with Herman von Holst who took over the practice. During the time following Wright’s departure, she designed fantastic examples of the Prairie School houses in Decatur, Illinois.

Marion Mahony Griffin, Adolph Mueller House, Decatur, IL, USA. Photograph by Randy von Liski via Flickr.

America’s (and perhaps the world’s) first woman architect who needed no apology in a world of men.

Reyner Banham, “Death and Life of the Prairie School” in: Architectural Review, 154, August 1973, p. 101. Pioneering Women.

In 1911 she married an architect, Walter Burley Griffin. They met during their work at Wright’s office, but Griffin decided to strike on his own, given that Wright had an almost black-hole-like gravitational field that devoured the talent of people working for him, and subjected it to the sole goal of growing Wright’s renown. Still faithful to the Prairie School style, the couple designed the Rock Crest–Rock Glen Historic District in Mason City, Iowa, a settlement of 16 houses all built in a consistent style.

Marion Mahony Griffin, rendering, un-built Henry Ford Dwelling, Dearborn, MI, USA, 1912, Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Pioneering Women.

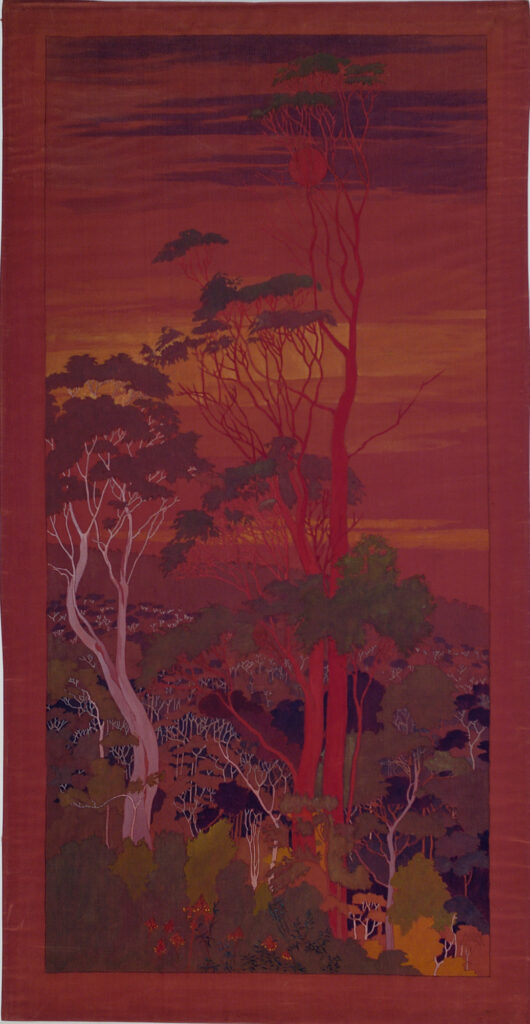

Always ambitious, Marion and Walter submitted their entry in a competition for the design of Australia’s federal capital in Canberra. Given that Walter had been younger, Marion was probably the driving force behind the submission. Certainly, it was her renderings that contributed significantly to the couple winning the contest.

By 1914 they had moved to Australia to oversee the realization of the project. The work was hard going, as the couple was perceived as external imposters and the local authorities and construction companies did not make things easy on them. The project was realized with major changes, but many features of their plan are still visible and recognizable in the city.

Marion Mahony Griffin, Eucalyptus Urnigera Tasmania/Scarlet Bark, Sunset, ca 1919, Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Pioneering Women.

As with Wright, so with Griffin, Marion had taken a back seat. She continued to work, design, render, and coordinate the office, but she kept pushing Walter to the fore. This is why it is now very difficult to distinguish her work from his, as it is all intermingled. In Australia they worked on multiple commissions, one of the more significant—apart from Canberra—was Castlecrag in Sydney, a town designed and developed by them.

Marion Mahony Griffin, Ceiling at the Capitol Theatre, 1921–1924, Melbourne, Australia, photo. Igor Hill, RMIT University.

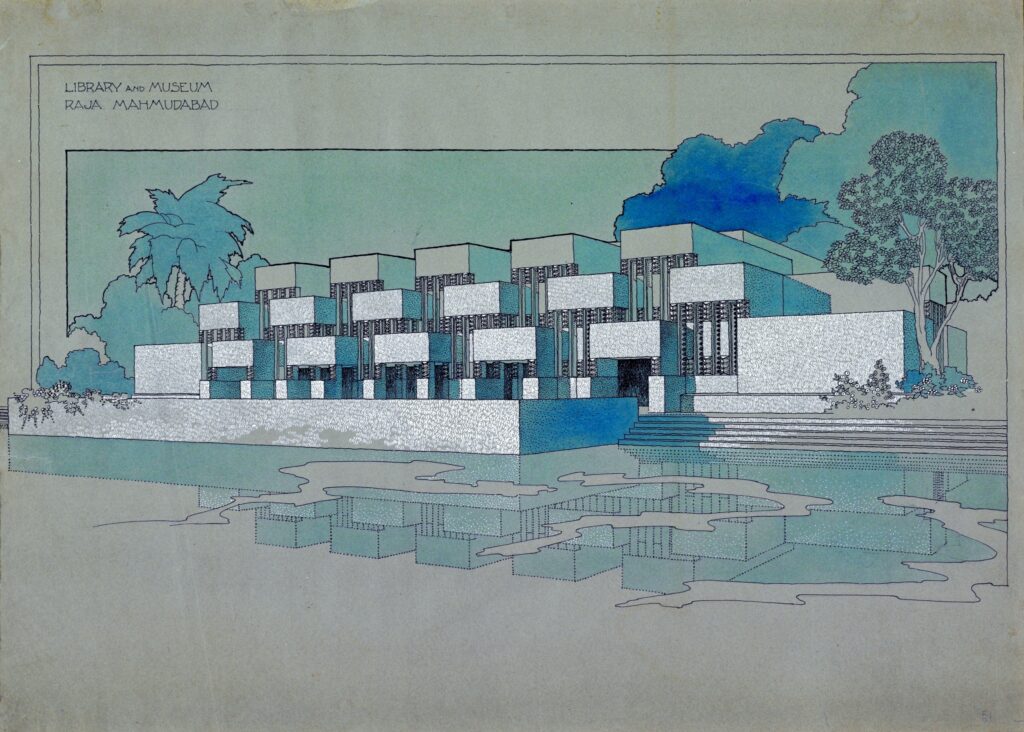

Griffin’s work in Australia was gaining a lot of interest and in 1935 Walter traveled to India to work on Lucknow University Library, with Marion joining him the following year. Unfortunately, Walter died suddenly in 1937. Marion initially planned to stay in India to finish the projects, but eventually went back to Australia to dissolve the practice there and then returned to Chicago. In the United States, she did some teaching but also devoted her time to writing an autobiography, The Magic of America. By then she was racing with dementia, a fight she inevitably lost. She died in 1961, forgotten and poor.

Despite that, she remains one of the greatest delineators of all time, she set a new standard for the profession and transformed the way we imagine architecture. Many of the early Frank Lloyd Wright commissions or that of her husband, Walter Burley Griffin, would never have materialized without her incredible talent in translating complex architectural design into a more accessible rendering that could seduce people with the money. Her inspirations with Japanese prints are clear, but she took that inspiration and made it her own, imbuing it with the meaning and feeling of the environment in which she worked.

Marion Mahony Griffin, renderer; Walter Burley Griffin, architect, Library and Museum for the Raja of Mahmudabad, 1937, Mahmudabad, India, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!