Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Marisol Escobar was a Venezuelan-American sculptor whose enigmatic persona and distinctive large woodblock figures caused a sensation during the 1960s. Despite being one of the most prominent artists of the burgeoning New York Pop Art scene, by the 1970s she had already faded into obscurity. Today, a recent resurgence of interest in Marisol and her artistic oeuvre is placing this female Pop icon back in the spotlight.

In 1961, Marisol Escobar caused an uproar when she made an appearance at a New York artists’ group at 39 East 8th Street, known as The Club. An exclusively male organization, membership included many of New York’s most important mid-century artists and thinkers, among them Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell. People were in utter disbelief at the site of Marisol wearing a white mask, which they shouted for her to remove as they stamped their feet. This disruptive stunt set the tone for Marisol’s enigmatic and unconventional career in the male-dominated world of Pop Art in the 1960s.

María Sol Escobar, known simply as Marisol, was born in Paris in 1930 to affluent Venezuelan parents. The Escobars traveled frequently between Venezuela, France, and the United States, exposing Marisol and her brother to different cultures. But Marisol’s exuberant childhood was abruptly curtailed in 1941 when her mother committed suicide. Marisol, age 11, vowed never to speak again—a decision she adhered to into her twenties. “Silence became such a habit that I really had nothing to say to anybody,” she told an interviewer in 1975.1 Her father sent Marisol to a boarding school on Long Island, New York, where she reportedly remained mostly silent. Silence was a large part of Marisol’s life and, in turn, would become an integral aspect of her artworks.

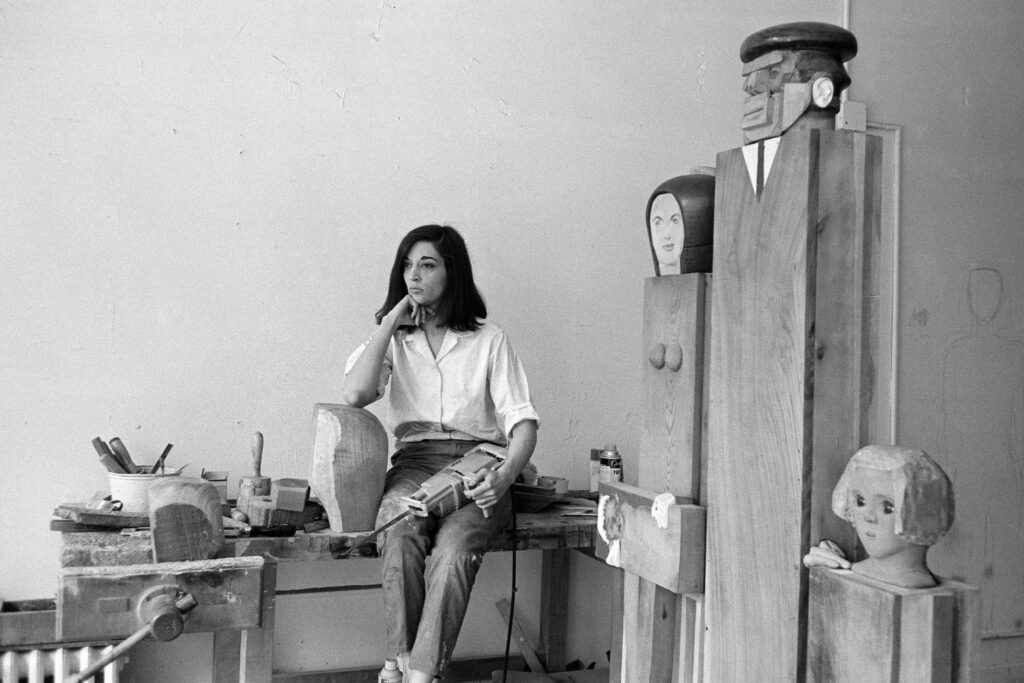

Marisol Escobar in her studio with her sculpture “The Kennedy Family,” 1964. New York Times.

As a young girl, Marisol loved drawing and was often the recipient of awards of excellence in her art classes. “I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t drawing,” she once stated.2 Marisol studied at l’École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian in Paris, the Art Students League of New York, and the New School for Social Research in New York. She was the student of famed abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann, whom she called “the only teacher I ever learned anything from.”3 Marisol practiced abstract expressionist painting for many years.

In 1953, inspired by an exhibition of pre-Columbian art in Mexico, Marisol began experimenting with sculpting. It was the artist’s small carved figures that soon piqued the interest of prominent New York art dealer Leo Castelli. In 1957, he included her in a group show and, that same year gave the artist her first solo exhibition at his gallery (even before Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg). But Marisol, who was averse to the limelight, panicked and fled to Rome.

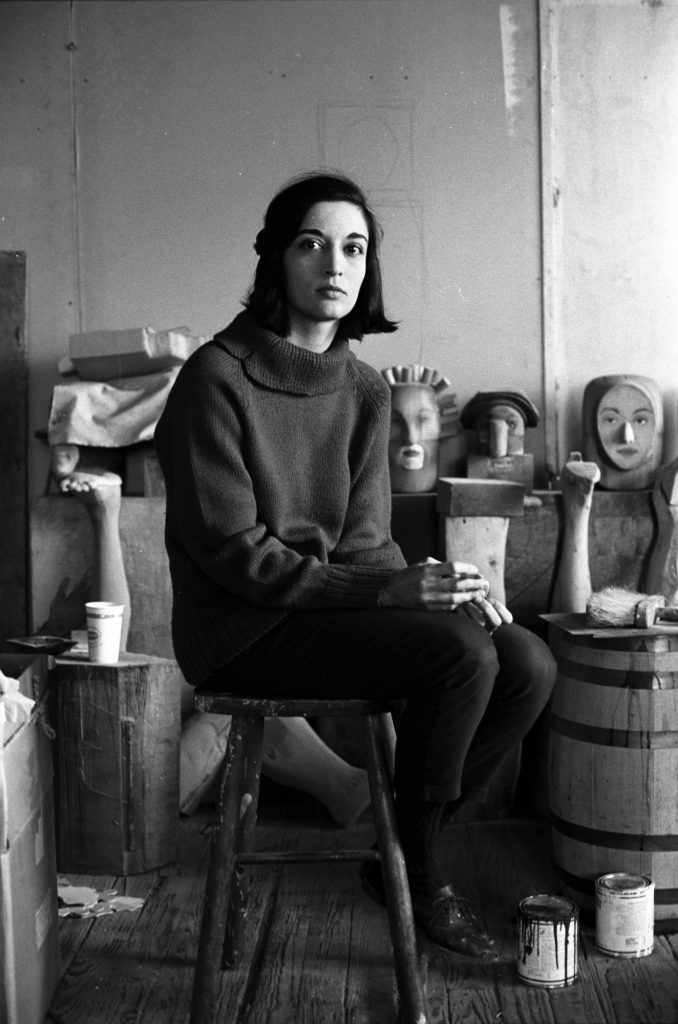

Marisol Escobar in her studio, 1963. Art News.

Despite working across a wide range of media, much of Marisol’s work is comprised of three-dimensional portraiture, with wood being her preferred medium. Influenced by the assemblages of Robert Rauschenberg, she espoused an aesthetic that merges Pop imagery and folk art. Her endearing totemic figures, which blend deadpan humor with irony, became her trademark.

Everything was so serious. I was very sad myself, and the people I met were so depressing. I started doing something funny so that I would become happier, and it worked.

1965 interview with the New York Times

A rebellion against abstract expressionism, as well as the post-war cultural climate, Pop Art reached its peak in the 1960s. It was the era of color television, Marilyn Monroe, Coca Cola, Elvis Presley, and the Kennedys—when the boundaries between high and low art began to be blurred. Like so many of her contemporaries, Marisol set out to create art from what she saw around her. Tackling current affairs and popular culture through a series of portraits, Marisol depicted celebrities such as Andy Warhol, French president Charles de Gaulle, and John Wayne.

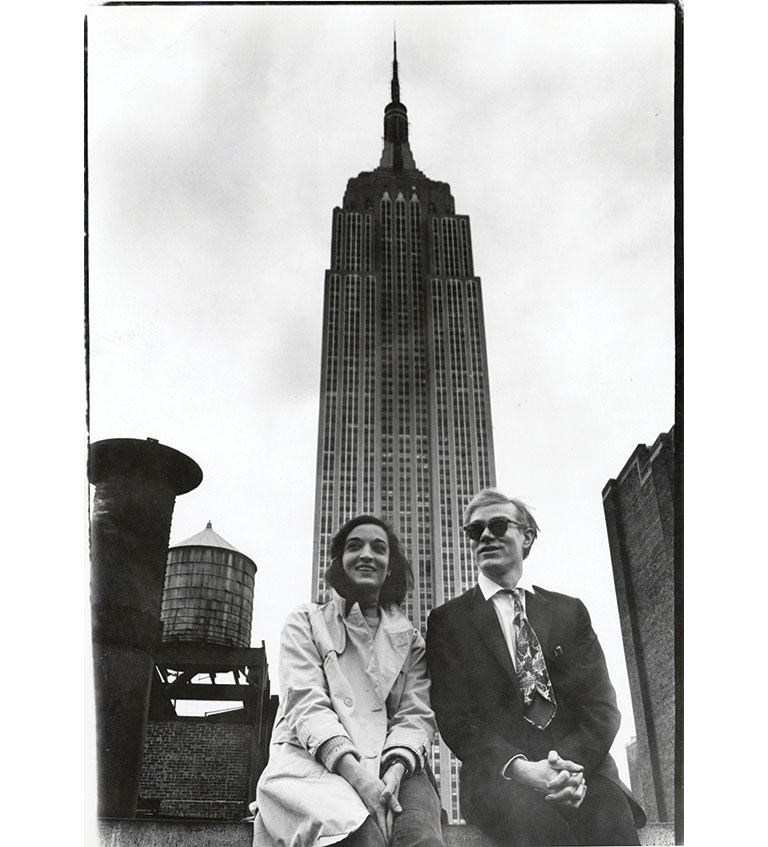

David McCabe, Andy Warhol and Marisol with the Empire State Building, 1965, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. Carnegie Museums.

Marisol became a fashion icon and New York it-girl, appearing on magazine covers and mingling with the biggest names in the business. Particularly notable was her friendship with Andy Warhol, who called her “the first girl artist with glamour” and cast her in two of his films, Kiss and The 13 Most Beautiful Women, both from 1964. Yet, despite being among the main players on the Pop Art social scene, Marisol always kept a safe distance.

I never wanted to be a part of society. I have always had a horror of the schematic, of conventional behavior. All my life I have wanted to be distinct, not to be like anyone else. I feel uncomfortable with the established codes of conduct.

At the peak of Marisol’s career, thousands of people lined up to see her shows. Her exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1966 drew the largest crowd in the history of the institution and in 1968 she represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale. But by the 1970s, her fame began to fade.

Now, nearly 50 years later, Marisol: A Retrospective seeks to revive a legacy nearly erased by time. A traveling exhibition, the show explores the artist’s oeuvre through an astounding 244 works that grapple with themes of politics, family, and women’s roles in society. In addition, visitors have the rare opportunity to come vis-à-vis with Marisol’s portraits of influential figures, including Andy Warhol, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Desmond Tutu.

The Party, 1965-1966, is comprised of 15 life-size freestanding wooden totems. Each figure features the face of Marisol herself, some photographed, others carved, and still others cast in rubber or plaster—a practice that would continue throughout her career. A satirical masquerade marked by tension and disengagement, The Party is a social commentary and criticism of the rituals of high society and the shallowness inherent to social interaction.

Marisol Escobar, The Party, 1965. Toledo Museum of Art.

Mi Mamá y Yo from 1968 is a figurative assemblage featuring the artist and her mother before her suicide. This autobiographical work depicts Marisol holding an outstretched umbrella over her mother’s head—perhaps a reference to the heavy burden of Marisol’s emotions. Marisol would produce various family groups throughout her career, likely as a way to work through her childhood traumas.

Marisol Escobar, My Mamá y Yo, 1968. Toledo Museum of Art.

Organized by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Marisol: A Retrospective is the largest retrospective of Marisol’s artwork, whose itinerary includes: the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (October 7, 2023 – January 21, 2024), the Toledo Museum of Art (March 2–June 2, 2024), the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (July 12, 2024 – January 6, 2025), and the Dallas Museum of Art (February 23–July 6, 2025). The exhibition draws largely on artwork and archival material Marisol left at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum before her death.

Throughout my life I have learned to be patient, to whisper, not to scream, to look beyond a square, to flow with the sea, to breathe the wind, and to be proud to be an artist.

Once hailed as the female artist of her generation, the stardom Marisol enjoyed in the 1960s has been largely written out of art history. A marginal figure compared to her male counterparts, she died in near obscurity in 2016 at age 85. But a recent resurgence of interest in Marisol and her noteworthy oeuvre is placing this female Pop icon back in the spotlight. Despite her introversion, Marisol never shied away from uncomfortable topics in her works. She provided an abundance of insightful commentaries on the politics and social interactions of the 1960s, making an invaluable contribution to the canon of Pop Art—a remarkable feat for someone who once claimed she didn’t have much to say.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!