Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

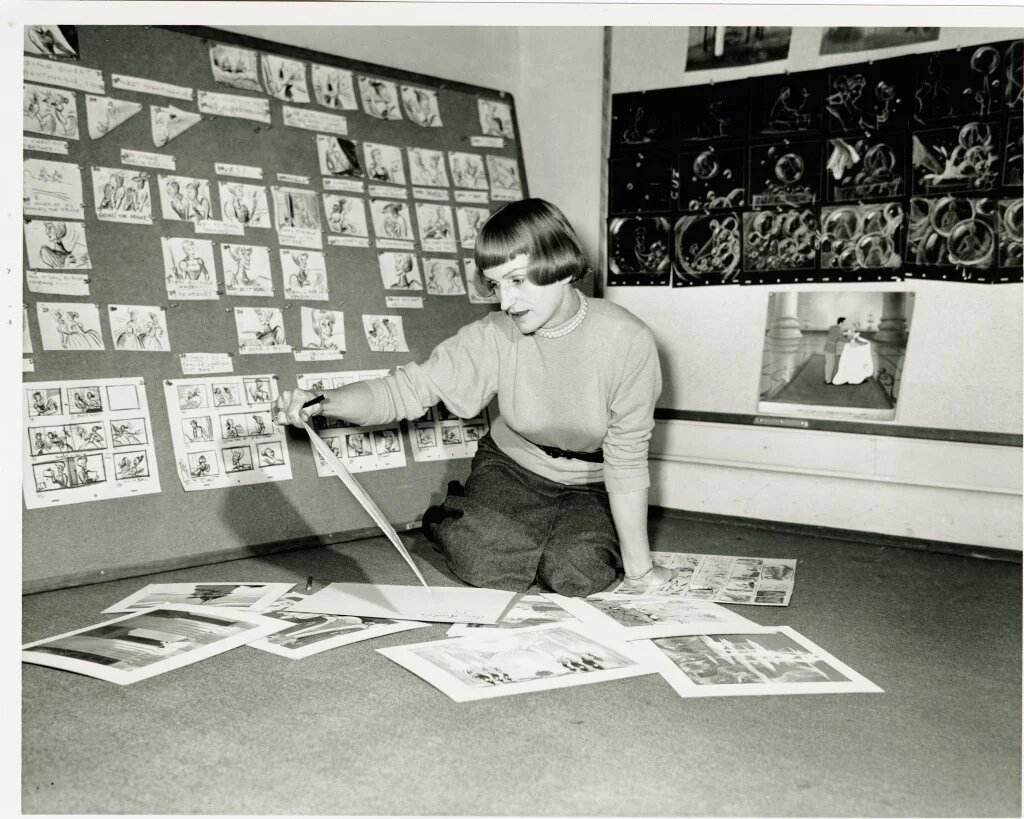

Inside the 2022 Wallace Collection’s magical exhibition, Inspiring Walt Disney, was an entire wall of intricate, hand-drawn illustrations from the 1950 animated film, Cinderella. Across a sequence of 24 images, the heroine’s torn rags are transformed into a beautiful ball gown by her wand-waving Fairy Godmother. These drawings pointed to the remarkable talent of Mary Blair (1911-1978) who, although initially disinterested in working as a concept artist, came to redefine the look of Walt Disney’s films forever.

Born in Oklahoma in 1911, Blair spent her earliest years defacing schoolbooks with sketches. At the age of 20, she earned a scholarship to study at the Chouinard School of Art in Los Angeles from 1931-1933, where she specialized in watercolor painting. Joining the prestigious California Watercolor Society, she was soon exhibiting at the Los Angeles Museum, San Francisco World Fair, and Chicago Art Institute, among other renowned venues.

Mary Blair. Laughing Place.

During the early 1930s, Blair worked for various animation studios but soon concluded that this wasn’t the career for her. Instead she wanted to pursue fine art and illustration where she could have more autonomy. “She decided she didn’t want to have anything more to do with animation, so she went home and started painting seriously”, recalled fellow artist, and her husband, Lee Blair.

Mary Blair, Cinderella, 1950, Concept art, gouache on board © Disney, The Wallace Collection, London, UK.

In the late 1930s, Lee joined The Walt Disney Company. It wasn’t long before his team sought to hire his wife, whom they considered the “better” artist. “With the necessary push from Lee, I reluctantly moved to sketch for Disney”, revealed Blair. Joining the Disney studio on April 11, 1940, she started creating story sketches for films such as Dumbo (1941). However, again frustrated at being unable to express her own artistic vision, on June 13, 1941, Blair resigned.

Then, a month later, her husband came home with news that changed her mind, and career, forever: Walt Disney had announced that he was taking a small party of studio artists on a two-month trip to South America. Blair, not wanting to miss out, made an appointment with Disney, who not only rehired her on August 8th, 1941 but agreed that she could join the tour. With the group, including her husband, she traveled across the Latin countries, including Argentina, Bolivia, and Brazil, among many others.

Mary Blair, Cinderella, 1950, Concept art, gouache on board © Disney, The Wallace Collection, London, UK.

Returning to the studio, and inspired by the tropical landscapes she’d seen on her travels, Blair replaced earthy browns, blues, and grays with a more vivid palette. Like many great modernists, including Georgia O’Keeffe and Henri Matisse, she experimented with simple lines and contrasting color combinations, applying unmixed paint directly onto the paper in blocks of unusually paired and intense shades. Disney was enchanted, as Blair remembered proudly: “Walt said that I knew about colors that he had never heard of before”.

Also influenced by the Indigenous dress and decorative arts, which she had encountered while overseas, Blair sketched increasingly simplistic, stylized renderings of naïve figures set within decorative backdrops, veering towards abstraction. To use her own words, she had been presented with “picture possibilities”, and recognized that each culture’s distinct “music, landscape, customs, and its people” could provide inspiration for her pictures.

“From then on everything was extremely interesting. The type of work now involved – inspirational sketches, styling, obtaining material on survey trips – was started by this trip to South America. From ’41 on I felt that I [had] found a place in the business. This also involves art direction and planning an art treatment of a picture”, Blair recalled.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Series 1, No. 8, 1919, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany.

For the short animation The Three Caballeros (1944), Blair drew a neon pink train racing around palm trees, which was included in the film. She presented the world as a wondrous place, where magic could be found not just in the realm of princess castles, but in the everyday. Disney must have recognized that he had an artist who could make his films not just more modern, but more magical too.

Fast becoming Disney’s favorite concept artist, Blair was invited to work on one of his biggest titles – the reworking of Charles Perrault’s Cinderella. This was a crucial time for the studio, which was emerging from the difficult years of World War II. While Disney wanted, and needed, to recreate the success of the earlier film, Snow White, he recognized that the next motion picture required a more contemporary mood. They had to look forward, not back.

Blair set to work, sketching ideas for the leading characters, including Cinderella and Prince Charming, as well as the film’s backgrounds before these visions were sent to the team of animators. As she described, her role involved “working with the writers and helping to create the ideas of the picture graphically right from… Its very beginning”.

Marc Davis, Cinderella, 1950, Clean-up animation drawing, graphite and colored pencil on paper, The Wallace Collection, London, UK.

Not only was Blair shaping the aesthetic of Disney’s films, she was also changing the company’s way of working. In contrast to earlier concept artists, she assumed a leading role in directing the animation’s atmosphere, palette, character styling, and movement.

For Cinderella, for instance, she drew 24 sketches for 18 seconds of movement, in which Cinderella’s rags are transformed into an exquisite ball gown, surrounded by spirals and sparkling stars. Blair was behind the film’s most memorable moment, and one which was apparently Disney’s favorite scene. Visible in the drawings are literally thousands of pencil marks representing the magic dust, all exactly positioned on multiple different sheets, which were then superimposed one after the other to create the special effect.

Blair also designed numerous other scenes and settings which were included in the film. Glorious gouache paintings show that she was the artist who created the dramatic vision of the Cinderella castle, imagined in iridescent blues, pinks, and golds. Playing with exaggerated scale, she was crafting a world as if seen through a child’s eyes. She used a similar palette to present the princess’ horse-drawn carriage, conjured by the Fairy Godmother, within an unusually blue woodland. An imaginative storyteller, Blair ensured that every scene, even the most mundane, became captivating for family audiences.

Mary Blair, Cinderella King’s Castle, Concept Painting, Walt Disney, 1950. Comics Ha.

Breathing new life into old fairytales, Blair proceeded to work on other classics from the 1940s to the 1960s, including Alice Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953). Acting much like Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother, Blair’s magical hand can clearly be seen in the dreamy mood of these animations, and she crafted more of the most memorable scenes, including the moment in Peter Pan when the children soar around the top of London’s Big Ben against a starry and deep blue night’s sky. For Alice in Wonderland, she made hundreds of gouache studies, in which the heroine falls down the rabbit hole into a technicolored world of unusual color contrasts.

Given her role, Blair felt “unlimited” in what she could achieve at Disney, explaining that there was “no discrimination against women. It [advancement] is merely a matter of ability”. Disney championed her and worked around her requirements – to the point that when the Blairs left California for New York in 1946, Disney kept Blair employed by the studio, visited her there and flew her back and forth for crucial meetings.

Movie still from Peter Pan, directed by Hamilton Luske, Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, 1953. Daily Constitutional.

In 1953 Blair finally left the Disney studio, pursuing a career as a professional painter and turning her hand to children’s book illustrations. Among her titles is I Can Fly (1951) – accompanying text by Ruth Krauss are Blair’s bold, joyful illustrations of a little girl who imagines being any creature that walks, hops, flies, or swims.

Although Blair had embarked on a freelance career, Disney wanted to continue collaborating with her. In 1963, he approached her to work on a boat ride for the United Nations Children’s Fund pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. Blair agreed and designed children from various cultures from around the globe, wearing distinctive costumes within flat and stylized scenes, imagined in brilliant colors.

The outside of It’s a Small World. Photo by Disney podcast @podmagical.

After the fair closed, Blair adapted the ride when it was moved to Disneyland and became the landmark attraction, It’s a Small World. It has since been replicated at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World Resort as well as Tokyo Disneyland, Disneyland Paris, and Hong Kong Disneyland. Within the parks, visitors can also see Blair’s influence on the characteristic Disney castle, painted in pinks and blues, as well as in various colorful murals, painted in her vivid palette.

Mary Blair’s design for the Sleeping Beauty castle, brought to life at Disneyland Paris. Photo by Joel Varughese.

From the very start of her career, Mary Blair wanted to be a painter and illustrator, rather than a concept artist within an animation studio. However, working with Disney, she created a unique position for herself, from which she could combine fine art, illustration, and storytelling. With pencil sketches and expressive gouache paintings, Blair defined the dazzling look and memorable scenes of many classic films. One of the greatest colorists of all time, today her work continues to transport audiences to another, more magical, world.

Author’s bio

Ruth Millington is an art historian, critic, and author, specializing in modern and contemporary women artists. She has been featured as an art expert on radio and TV, including BBC Breakfast, Sky Arts and ITV News. Ruth has written for national newspapers, including the Telegraph, the I and The Sunday Times. Her first book Muse uncovers the hidden figures behind art history’s masterpieces. You can follow her on Twitter at @ruth_millington.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!