Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Mary Cassatt was the only American painter who exhibited with the Impressionists. Although she never married or had children of her own, she is best known for her delicate portrayals of motherhood. Her paintings seek to break traditional barriers in art and emphasize the vital role of women as the primary caretakers of children. We have selected five of the most beautiful paintings by Mary Cassatt!

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926) was an American painter and printmaker born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh). In 1865, she moved to Paris to work under the guidance of the academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme. After spending some time in Italy studying the paintings of Correggio and Parmigianino, she returned to France in 1874 where she began exhibiting at the Salon.

Cassatt was the only American artist officially associated with the Impressionists. In 1877, she befriended Edgar Degas (1834–1917), who asked her to join the independent group of artists and participated in four out of the eight Impressionist exhibitions. Her technique and composition evolved under Degas’ influence, who also encouraged her to dabble with printmaking — ukiyo-e woodcut prints were very fashionable among the Impressionists (and later Post-Impressionists). Her relationship with Degas was a close one; both of them shared an experimental and dynamic approach to painting.

Cassatt was mainly interested in figure compositions. During the late 1870s and early 1880s, she depicted primarily her family, theaters, and the opera. Over time, however, she distanced herself from the Impressionists and, by 1886, was no longer part of any art movement.

Marry Cassatt, Mary Cassatt Self-Portrait, c.1880. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA. Museum’s website.

Although marriage and motherhood were incompatible with her grand career ambitions, later in life, Cassatt expressed an interest in portraying the mother-child relationship, for which she is widely renowned today.

Cassatt hoped to reinvent the traditional portrayals of Madonna and Christ Child painted by the Italian and French masters, by marrying traditionalism with novelty. Many of her initial series of mothers and children share common traits, such as simplicity and clarity, with those found in Renaissance art. Because of this, she was named “la sainte famille modern” (the saint of the modern family) by art dealers such as Paul Durand-Ruel.

Raphael, Madonna and Child, c. 1505, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Regardless, Cassatt adopted a deeply secular and realistic approach to the theme, seeking to rediscover conventionally religious subjects by readapting them to be fit for modernity.

Her work during this period focuses entirely on the relationship between mother and child, rejecting feelings of sexuality in the traditional sense of the word. Cassatt places an important emphasis on physical touch, which is viewed as a sign of intimacy. She strives to present women in a sensual and emotional light that admits sexuality only through the prism of their motherliness.

Regarding it as an invitation for men to treat women as erotic objects of desire, Cassatt rejected the female nude, all of her adult subjects being clothed. Many children in her paintings, nonetheless, are painted naked, for example, during bath time. Children, in her perception, symbolize purity, goodness, and genuineness; in fact, many of her works bear symbolic or allegorical meanings.

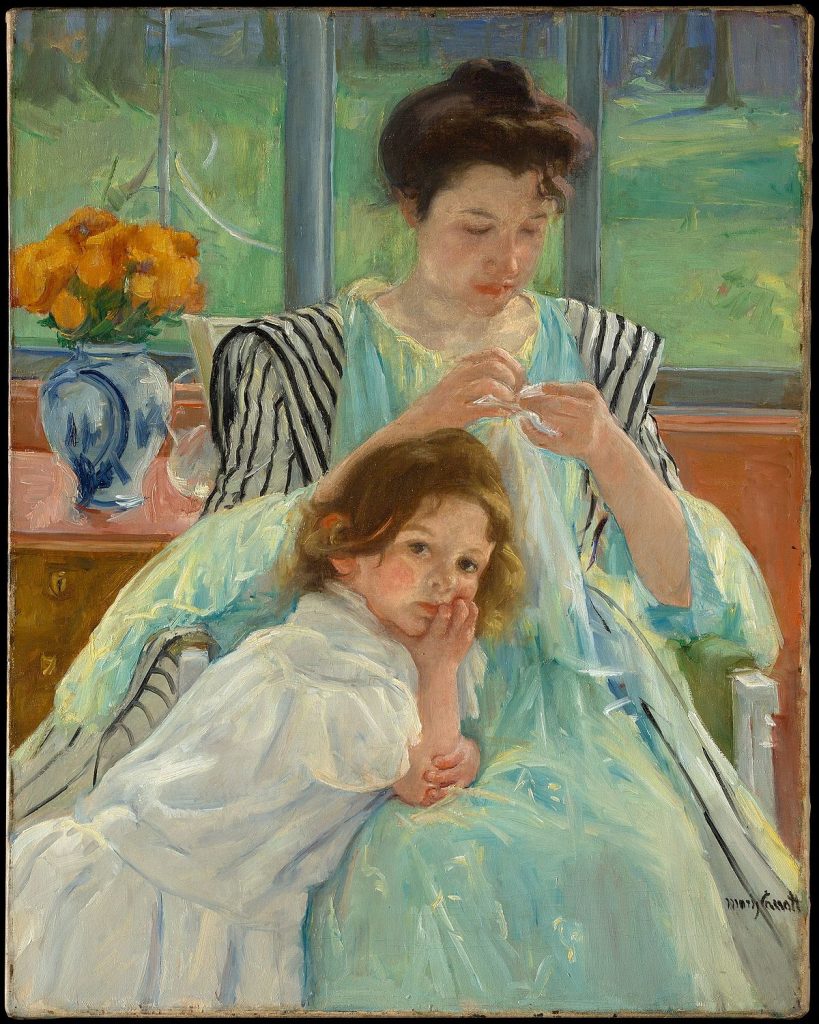

Mary Cassatt, Young Mother Sewing, 1900, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Painted in 1900, Young Mother Sewing depicts a young child resting on her mother’s lap, gazing almost nostalgically into the distance. The woman is sewing silently in front of a wide window. She is wearing a striped dress and a green apron. Cassatt used two unrelated models for this painting to reenact the heart-warming scene. The artwork was bought one year later after its completion by Louisine Havemeyer, who noticed:

Look at that little child that has just thrown herself against her mother’s knee, regardless of the result, and oblivious to the fact that she could disturb “her mamma”. And she is quite right, she does not disturb her mother. Mamma simply draws back a bit and continues to sew.

Louisine Havemeyer (1855–1929) was a patron of the Impressionists, a philanthropist, and last but definitely not least, a feminist. Havemeyer was one of the most preeminent voices who contributed to the suffrage movement in the United States.

Mary Cassatt, The Child’s Bath, 1893, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

As one of Cassatt’s masterpieces, The Child’s Bath has an unusual composition. The lively patterns found in the background and on the woman’s dress contrast with the child’s nakedness, while the higher vantage point keeps the viewer at a distance only as an observer; not as a full participant.

Bath time, it seems, is an intimate activity. As the child watches patiently, the mother (or nurse) is sprinkling water over her delicate legs. The woman is encircling the child with an arm pressed gently against her.

Cassatt’s preference for pictorial flatness, cropped forms, and striking bold outlines was inspired by Japanese wood prints.

Mary Cassatt, The Boating Party, 1893–1894, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Cassatt spent many summers, after 1893, near the Mediterranean in Antibes, France. During this time she played with vibrant, decorative colors and with different geometric shapes. The horizon line is at the top of the painting, diminishing the sense of distance. We don’t know who the woman is, but it’s safe to assume that from the way she holds the child she could be the mother.

This ambitious painting was the centerpiece of Cassatt’s first solo exhibition in the United States. It’s also one of her biggest artworks, reaching 90 x 117.3 cm in dimension.

Mary Cassatt, Maternal Caress, c. 1896, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Museum’s website.

In Maternal Caress, Cassatt captured a lovely display of affection between a mother and her child. They are outside, presumably in a garden. The background is sketched lightly, shifting the focus to the mother and child.

The up-close composition directs the viewer’s gaze over the mother’s shoulder, who is holding her child carefully. In the painting, Cassatt highlighted her subjects’ rounded forms. The girl looks inquisitively at her mother, fixing her eyes on her face. She places a hand on the woman’s cheek, like many children do, as though to examine her features in detail.

Mary Cassatt, Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror), c. 1899, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

This painting, also known as The Florentine Madonna, suggests a resemblance to the Italian Renaissance images of the Virgin and Child. The child poses in contrapposto, the mirror behind his head creating the impression of a halo. His mother’s face is filled with joy and love as she holds him tenderly in her embracing arms.

Degas told Cassatt that the painting

Has all of your qualities and all your faults—it’s the Infant Jesus and his English nurse.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!