Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

An artist and naturalist, Mary Vaux Walcott was an extraordinary and accomplished woman. Sometimes called ” the Audubon of Botany”, she is best known for her five-volume North American Wild Flowers. In addition to drawing and painting botanical images, she was an adventurous and knowledgeable explorer of the North American West.

Mary Vaux Walcott in 1924. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Mary Vaux Walcott (1860–1940) was born in Pennsylvania to the prominent Vaux family of devout Quakers. The Quakers are a group of Christians who practice simple, communal worship without formal rituals or clergy. Quakers value pious, non-luxurious lives, but many have been quite wealthy and prominent Americans. This faith is particularly popular in Pennsylvania, since state founder William Penn was himself a Quaker. Quakers have long believed in the relative equality of the sexes, which is perhaps why so many prominent 19th-century American women came from Quaker backgrounds.

In accordance with the emphasis on simple living, Quakers of Walcott’s time did not participate in the arts. However, they placed a great deal of value in science. The study of the natural world, including recording it in photographs and sketches, was seen as a particularly good way to appreciate God’s works. Mary Vaux Walcott’s father, George Vaux VIII, was certainly interested in nature. He took Mary and her two brothers on expeditions to the Canadian Rockies starting in 1887. A consummate traveler, Walcott would continue making regular trips to the region for the rest of her life.

Mary Vaux Walcott, Western Azalea (Rhododendron occidentale), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

During her voyages, Walcott’s relentless curiosity kept her busy. She would scale mountains, explore caves, hike, ride horses, measure the retreat of glaciers, study wildlife, and paint or photograph the local flora. She became so knowledgeable that she frequently gave lectures and wrote publications about the Canadian Rockies region. Walcott also joined many learned societies for women. She even had a mountain, Mount Mary Vaux, named for her in Alberta, Canada.

In 1914, Mary Vaux married Charles Doolittle Walcott (1850-1927), a scientist whom she had met in the Canadian Rockies. Dr. Walcott, a widower, was secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, a major American organization dedicated to spreading scientific and cultural knowledge. In her new husband, Mary Vaux Walcott found a supportive collaborator whose connections opened doors for her. By all accounts, it was a perfect match that brought happiness to both parties. The Walcotts lived together in Washington, DC, where they ran in the same social circles as presidents, congressmen, and diplomats. However, they also continued to travel regularly to the Canadian West to conduct their explorations and research until Charles’s death in 1927.

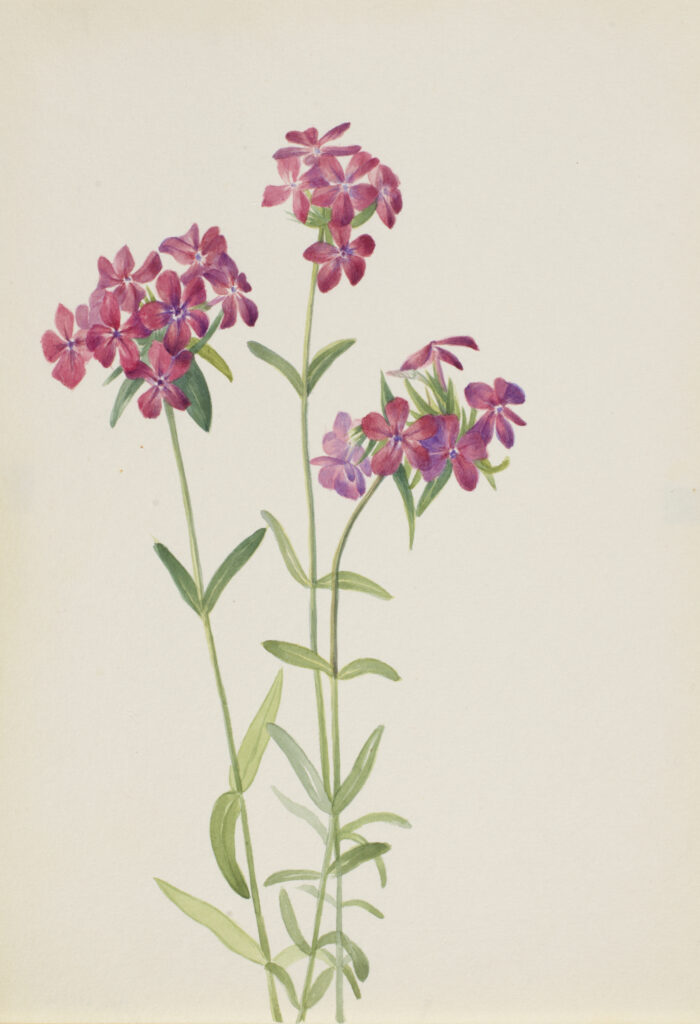

Mary Vaux Walcott, Hairy Phlox (Phlox amoena), ca. early 1930s, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

In 1925, the Smithsonian published the five volumes reproducing Mary Vaux Walcott’s watercolor paintings of wild flowers. Titled North American Wild Flowers, this series included 400 of Walcott’s images in total. Unquestionably Walcott’s masterpiece, this work earned her the title “Audubon of Botany”. Reviewer Charles H. Sargent bestowed that title upon her in his 1927 review for The Boston Transcript.1 Each volume included 80 unbound plates and a softbound book of text, together in a slipcase embossed with the Smithsonian logo. North American Wild Flowers proved popular enough to warrant re-issue in a single volume in 1953. Walcott also provided the illustrations for a 1935 publication of North American Pitcher Plants, which is now viewable online.

As her talents and knowledge didn’t end with illustration, Walcott also contributed all the text in North American Wild Flowers. She provided a paragraph or two of basic information about each plant, sometimes also giving a few details about the circumstances in which she found the specimen. In her forward, she elaborated on the pains she had taken to observe and record some of the plants growing in relatively inhospitable circumstances.

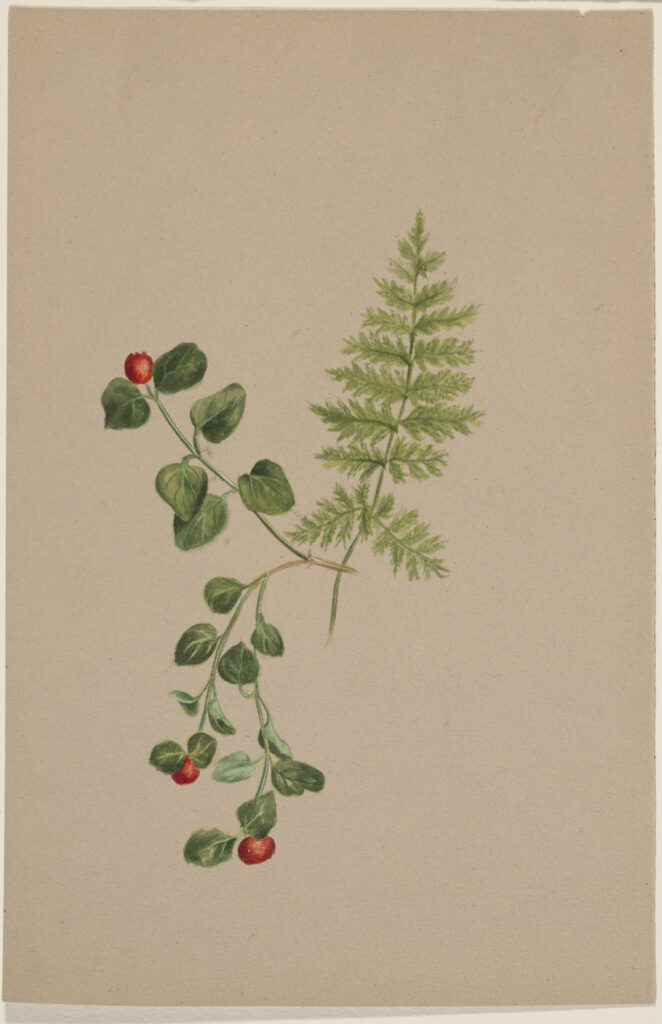

Mary Vaux Walcott, Partridgeberry (Mitchella repens), ca. 1883, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Many of the western sketches were made under trying conditions. Often, on a mountain side or high pass, a fire was necessary to warm stiffened fingers and body. In camp, the diffused light of the white tent was a great handicap, and considerable ingenuity was required to obtain a proper combination of light and shade. […] The short lives of the blooming plants definitely limit the number of sketches that can be made during a single field session, for many hours of work are necessary to finish a single sketch, and wild flowers wither quickly. […] The limited habitat of others made it necessary to take long rides and climb high above the timber line to procure them, and frequently no trails were available.

Forward to North American Wild Flowers, Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1925.

While many of the images in North American Wild Flowers came out of such challenging circumstances, others did not. According to Walcott’s text, some specimens came from her frequent haunts in Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Washington D.C. Others were provided to her by friends across the country.

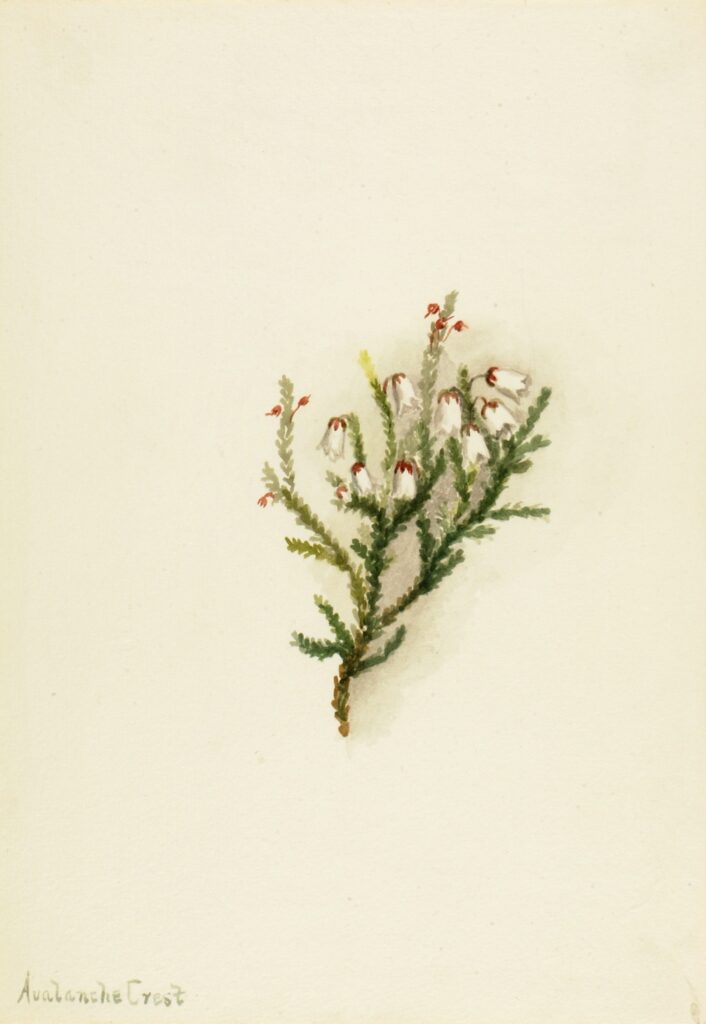

Mary Vaux Walcott, Cassiope (Cassiope mertensiana), ca. 1900-1905, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Unusually for the time, Walcott’s botanical illustrations depict each subject at life size. The smallest plants fill just a portion of the page. The larger ones only appear in part. The effect is particularly arresting when viewing the images in person. Walcott’s botanical illustrations are detailed and sensitive, evidencing her close observation of each plant. It’s no wonder that it took her about ten years to create all of the images.

The vibrantly-colored plants appear silhouetted against plain white backgrounds. Aside from a few roots, they do not usually reference their natural settings. This compositional scheme emphasizes the solidity of some plants and delicacy of others. Even tiny spines on stems and leaves appear clearly. Walcott’s images are precise without being harsh, as natural illustrations can be at times. Some images convey saturation and solidity, while others appear more ethereal. The selection includes all sorts of plants, some shown with flowers and others without, from all different climates. Beyond wildflowers, Walcott also included cacti, cones from trees, berries, and more. Photographs on a screen simply can’t convey the full effect of the high-quality prints.

Mary Vaux Walcott, Untitled Flower Study, ca. 1883-1900, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Although the Walcotts donated Mary’s 400 watercolors and associated writings to the Smithsonian, North American Wild Flowers was still quite expensive. A limited edition of 500 copies, sold by subscription, helped to finance production. There was a tremendous cost associated with faithfully reproducing Walcott’s vivid colors and painstaking detail in print form. William Rudge’s special halftone printing process was chosen for the task. He printed Walcott’s works on a thick, durable rag paper.

Walcott left several hundred of her watercolors, many more than just those that appeared in North American Wild Flowers, to the Smithsonian. She also gave her paintbox that she took on all her long and challenging journeys of exploration. The Smithsonian American Art Museum now owns her works, viewable on the museum’s excellent website.

Sargent, Charles H. “An Audubon of Botany, Mrs. Walcott’s Monumental Work on Wild Flowers”. The Boston Transcript, February 12, 1927.

Henson, Pamela M. “Mary Vaux Walcott’s Wild Flowers“. Smithsonian Institution Archives. March 26, 2015.

Jones, Marjorie G. The Life and Times of Mary Vaux Walcott. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing ltd., 2015.

McLoone, Margo. Women Explorers of the Mountains: Five Photo-Illustrated Biographies, Nina Mazuchelli, Fanny Bullock Workman, Mary Vaux Walcott, Gertrude Benham, Junko Tabei. Mankato, MN: Capstone Books, 2000.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!