Historical Context

The French Renaissance was an exciting time period in French art, history, and culture. It lasted almost 200 years, roughly beginning with Charles VII in 1422 and ending with Henri IV in 1610. During this vibrant era lived the artist François Clouet (ca. 1510 – 1572) who dominated the French court for over 30 years from 1541 onwards. He created a typically French Renaissance style by infusing Italian ideas of naturalism and linear perspective with French ideas of decorative patterning, fine details, and royal majesty. Clouet’s style was so universally revered that contemporary artists emulated and propagated his style even after his death in 1572. Portrait of Louise de Lorraine, created in 1575, is an example and a masterpiece of this posthumous School of François Clouet.

General Composition

Louise de Lorraine is a large oil on canvas measuring 44 ¾ inches wide by 57 1/4 inches high or 113.7 centimeters wide by 145.4 centimeters high. Its expansive canvas material would have been expensive in the late 16th century when most portraits were painted on less expensive wood panels. However, a royal portrait justifies the additional expense as it reflects upon the majesty of the subject and the monarchy.

Queen Louise de Lorraine

The subject is Queen Louise de Lorraine who was the wife of King Henri III from 1553 to 1589. She was noted by courtiers as being young, beautiful, and elegant, and the artist certainly captures these graceful characteristics. The queen stands against a black background while she wears a red dress richly embroidered with gems, pearls, silver and gold thread, and white lace. She rivals Queen Elizabeth I of England, a more famous contemporary, in her magnificent clothing, white skin, and commanding presence. If the Queen of France Louise de Lorraine had been an English noblewoman, she would have been a serious rival as a court beauty to the Virgin Queen in Tudor England.

Artist’s Vision

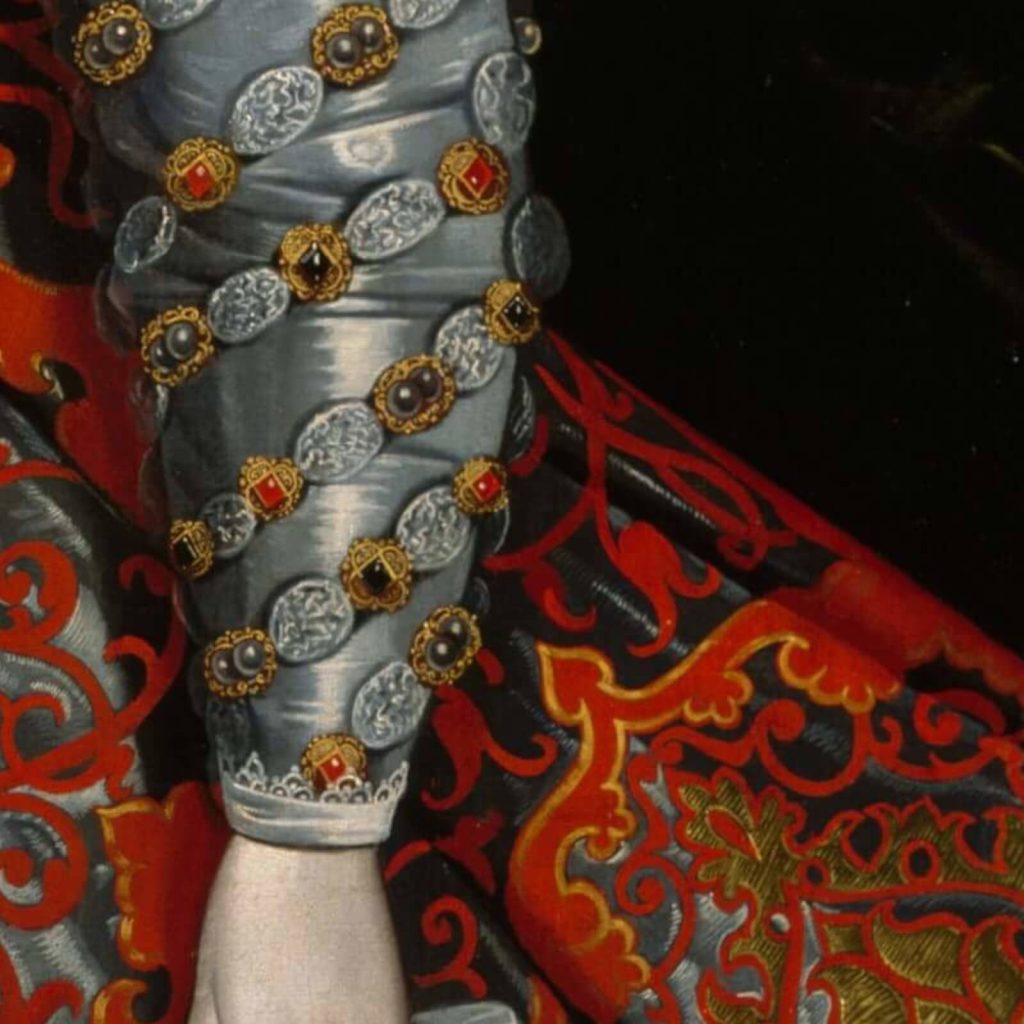

Portrait of Louise de Lorraine is a royal portrait combining the artist’s vision, the subject’s personality, and the monarchy’s promotion. François Clouet was known for his formalized elegance. He would balance between naturalistic details and patterned grace. For example, the red silk fabric of the skirt is not rippling in small natural rumpled folds. They instead sweep in large flat diagonal panels beginning at the queen’s waist and cascade off the canvas edges. The grey fabric in the front of the skirt is also flattened and wrinkle-free, but its monumental presence adds to the queen’s statuesque aura. The flattened and shadowless neck and forehead also add to the queen’s otherworldly stature. The queen almost appears immobile and iconic in her grandeur.

Subject’s Personality

What is interesting is that Clouet’s vision of the proud queen is contradictory to the queen’s actual personality. She was beloved by King Henri III because she was his ideal wife through her modest, tender, and reserved nature. King Henri III did not want another strong, proud, and domineering woman in his life. Queen Mother Catherine de’ Medici was meddlesome and annoying enough for him without adding to the court dynamics an equally bothersome wife. Louise also fit the ideal female French Renaissance beauty standards through the painting’s pale delicate cheeks, wide doe-like eyes, and smooth white skin. She exudes lightness and ease despite the dripping opulence of her dress and accessories.

Monarchy’s Promotion

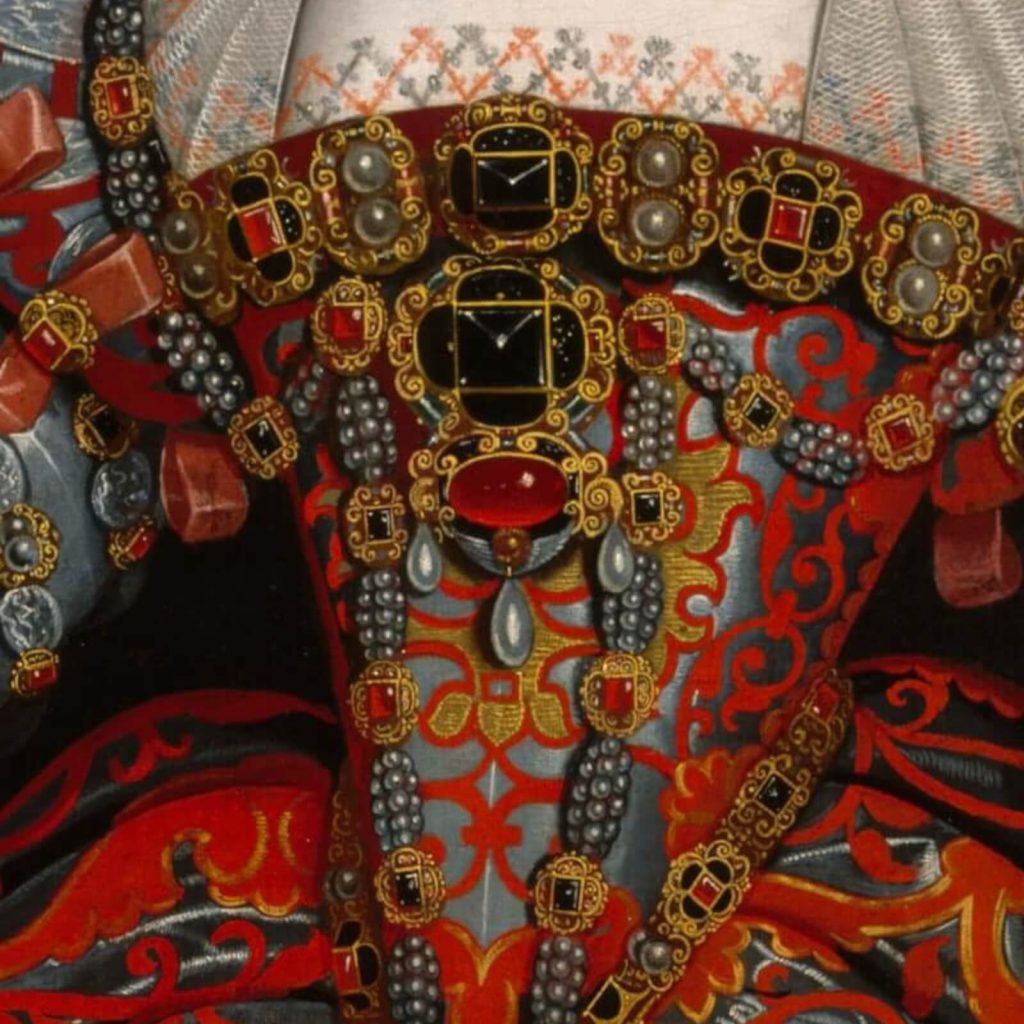

What can be said about Queen Louise’s outfit? It is absolutely majestic, marvelous, and magnificent. These three adjectives describe the hopes of every European monarchy desiring to promote its status on the world stage. Her outfit speaks about the monarchy’s aspirations through its materials’ implications.

White Pearls

The pearls around her neck, in her hair, and scattered throughout the dress are Renaissance symbols of sexual purity. Queen Louise desired to be seen as sexually faithful to her husband, and therefore prevented any paternity questions when she birthed a male heir to the throne. Sadly, the marriage proved fruitless and the queen was eventually declared barren. What is worse is that King Henri III was unfaithful to Queen Louise with several mistresses. Hence, doesn’t the portrait have an aura of sadness especially seen in the queen’s eyes? It is as if Queen Louise is saying, “I know he is unfaithful but I suffer in silence.” The handkerchief certainly implies she has been crying.

White Lace

Additionally, the white lace adorning her dress neckline and sleeve cuffs declare the queen’s cleanliness and wealth. During the Renaissance period in Europe, bathing had seriously fallen out of fashion. It was widely believed that sitting in hot water exposed the body to unhealthy miasmas (vaporous airs) that caused sickness and death. Therefore, washing only the exposed areas of the skin, such as the face, the neck, and the hands in cold water became the cleanliness norm. White lace frequently touched these exposed areas and declared the cleanliness of the wearer. Therefore, the nobility and royalty of the time would frequently change their laces, sometimes daily during hotter months, as a form of good hygiene and social status.

Multicolored Silk

Finally completing the material propaganda are the red, black, and grey silks of the queen’s dress. Silk today is still an expensive material, but it was prohibitively expensive during the French Renaissance. Only the super-wealthy could afford silk as a clothing option. Wearing silk was a sign of prosperity, luxury, and high social status. It was interestingly also a sign of French patriotism. The French city of Lyon was and still is famous for its silk textile manufacturing. Consequently, French royalty and nobility for centuries wore silk as financial and patriotic support to the French silk industry. Therefore, Queen Louise in her portrait proudly proclaims her royal position and French patriotism.

Amusingly, Queen Marie Antoinette centuries later in the 1780s would become the scorn of the silk industry when she began regularly wearing cotton and linen dresses. She and her fashion followers monetarily crippled Lyon as silk fell out of fashion and demand for it evaporated. Emperor Napoleon I later reversed this trend in the early 1800s, and Lyon’s silks were once again royally supported and prospered.

Italian Influence

Louise de Lorraine is a French portrait, but it has some strong Italian influences, specifically Florentine, throughout its composition. The city of Florence is widely considered the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance, and its cultural impact was widespread. For example, the dark green curtain in the upper right corner is a typical Florentine motif in 16th-century portraits. It adds subtle interest to the otherwise flat plain background. It also helps frame the subject by adding some volume to the image’s right side. This drapery swag would later intensify a century later during the Baroque period when both Italian and French portraits placed vibrant red fabrics along their borders and backgrounds.

Mannerist Hands

Also reflecting Florentine influence are the elongated hands of Queen Louise. Italian Mannerism was prominent in the 1570s and is considered the inheritor of the Italian Renaissance. It was a period of experimentation when the Renaissance “rules” of balance, proportion, and symmetry were being tested and broken. An elongation of the hands was one such motif. Visually it is very elegant and aristocratic. Anatomically it is disproportionate and unnatural. Therefore, Louise de Lorraine and François Clouet have injected some contemporary Italian motifs to infuse this French portrait with international stylishness.

Youthful Hope

Louise de Lorraine is a striking portrait of a French queen that ruled only for 14 years. After her husband’s assassination in 1589, Queen Louise retired as a recluse to the Château de Chenonceau in the distant countryside. She discarded her public finery and assumed a modest almost nun-like existence. Therefore, Louise de Lorraine captures the queen during her early reign before the adversities of infertility, infidelity, and widowhood. It reflects the glory of François Clouet, the French court, and the French Renaissance. C’est magnifique !