Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

26 January 2025 min Read

Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps is one of the most famous and politically iconic images of European art history. However, it is a deepfake.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France.

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) was the most important and influential painter of Neoclassical France which roughly lasted from the 1780s to the 1820s. He studied under Joseph-Marie Vien (1716-1809), a prominent Neoclassicist, and then won the 1774 Prix de Rome to study art in Rome. When David returned to France 10 years later in 1784, he was filled with ancient Roman values of patriotism, heroism, and duty. He believed that French art should be direct, forceful, and clear to arouse the viewers’ allegiance and assistance to France. David achieved it through Napoleon Crossing the Alps, as it has become one of his most famous and politically iconic images.

Jacques-Louis David, Self-Portrait, 1794, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps is an oil on canvas with a portrait orientation measuring 234 cm wide and 273 cm high. It was painted in 1802 and is actually one of five versions of General Napoleon riding his horse across Mount Saint-Bernard. This version is arguably the most popular version because it is the most-viewed version hanging inside one of the most visited places on Earth: the Palace of Versailles (Château de Versailles), Versailles, France.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

The painting presents Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), the great general and later Emperor of France, during one of his many military campaigns. The painting shows Napoleon and his army crossing the Alps through the Mont Saint-Bernard passage on May 20th, 1800. Napoleon wears a glamorous military uniform of blue, white, and gold fabric with a swirling red cape. His gray-white Arabian horse, Marengo (c. 1793–1831), rears in an energetic pose. Napoleon looks at the viewer with a steely look of confidence as he points to the rising landscape in the direction of victory.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

What is deeply surprising, interesting, and perhaps ridiculous is that the painting is a fabrication of imagination. Yes, Napoleon and his army did cross the Alps on May 20th, 1800. Yes, Marengo joined Napoleon on the trek. However, Napoleon did not ride Marengo through the Alps. He did not wear this outfit. He did not appear so youthful and confident. Jacques-Louis David painted a publicity portrait for Napoleon to promote his greatness and military prowess by replacing historical accuracy with flashy attraction. The viewer is presented with a razzle-dazzle version of reality. This is a 19th-century Instagram portrait with many filters and manipulations.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

Napoleon’s gorgeous outfit is not a cold-weather outfit. It is not warm, padded, or practical. It is rather the vibrant uniform and Mamluk-style saber of a general waging into battle. This specific outfit was worn during the victorious Battle of Marengo on June 14th, 1800. Therefore, Napoleon did not wear this uniform while trekking across a dirty, rugged, cold mountain. Napoleon, in reality, is recorded to have worn a simple traveling fur outfit with a thick wool gray coat. Less pretentious, less portrait-worthy, but definitely more practical.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

Marengo, the trusted grey steed, did follow Napoleon across the Alps. However, Napoleon did not ride him through the Alps. The terrain would have been too uneven and icy to safely ride Marengo. Both Napoleon’s and Marengo’s legs and lives would have been at risk. Therefore, what did the almighty and powerful Napoleon ride through the Alps? A donkey. A little short fat brown donkey. Definitely not worthy of a glamorous portrait.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

Jacques-Louis David continues with the Instagram-worthy filters when it comes to Napoleon’s age. Napoleon was 31 years old when he completed the Mont Saint-Bernard pass, but he appears to be more youthful, closer to 25 or 26. Why did David not paint a 31-year-old Napoleon in a gray coat riding a brown donkey? The answer lies between Napoleon’s instructions and stubbornness.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

When Napoleon commissioned Jacques-Louis David to paint his portrait, Napoleon instructed him to paint “calme sur un cheval fougueux” or “calm, mounted on a fiery steed.” Hence, donkey out and horse in. Napoleon then sent his general uniform to David to use for the portrait’s clothing. Practical winter wear out and fancy clothes in. Napoleon then refused to sit for David to model his facial likeness. Napoleon stated everyone knows me, they know what I look like. David responded by asking for one sitting because he wanted to capture the best likeness from real-life observation. Napoleon refused. In frustration, David used a portrait bust that was created several years earlier as the model for his painting. 31-year face out and 25-year face in. Which begs the question, is there anything historically accurate painted into the scene? Not much because the weather was actually fine and sunny, but David painted it cloudy and stormy to make the scene more dramatic. Oh my goodness! Fake portrait alert!

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

No, in all seriousness, the verisimilitude or the lack of verisimilitude does not ideologically impact the painting because Napoleon Bonaparte and Jacques-Louis David were not trying to capture a photorealistic image of an historical event. They wanted to capture an idealized image, an idea, a concept, a vision. It was political propaganda. They wanted to capture the public’s imagination of Napoleon’s patriotism, heroism, and duty. He is fighting for France. He is a French hero. He is fulfilling his duty. A young handsome man in flashy clothes riding his fierce horse in a snowy landscape against unseen enemies evokes strong emotions. A man in an itchy gray sweater riding a donkey on a sunny clear day does not sound very exciting. It sounds rather boring and forgettable. Napoleon and David knew this and curated the image to become a political emblem.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

The heroic and idealized Napoleon raises his right arm towards the Italian enemies. The army scrambles in the background to wheel the cannons through the passage. Battle approaches as the blustery wind whips Napoleon’s cape around in a fury. The scene is energized by action, and it is further energized by the implied diagonal lines hidden throughout the composition. Highlighting in color clearly reveals the lines. The red foreground is completed by the top of Marengo’s front left hoof, the bottom of Marengo’s front right hoof, the top of the cannon wheel, between Marengo’s back hocks, and touches the foreground. The yellow background is formed by the top far left mountain, the top of the second left peak, and then the top of Marengo’s rump. Napoleon’s body forms a blue line with the top of his forward cloak, through his wrist, the top of his ear, and the top of his cloak shoulder. These three visual lines create energetic movement that increase the drama of the battle maneuver.

Visual Lines. Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France.

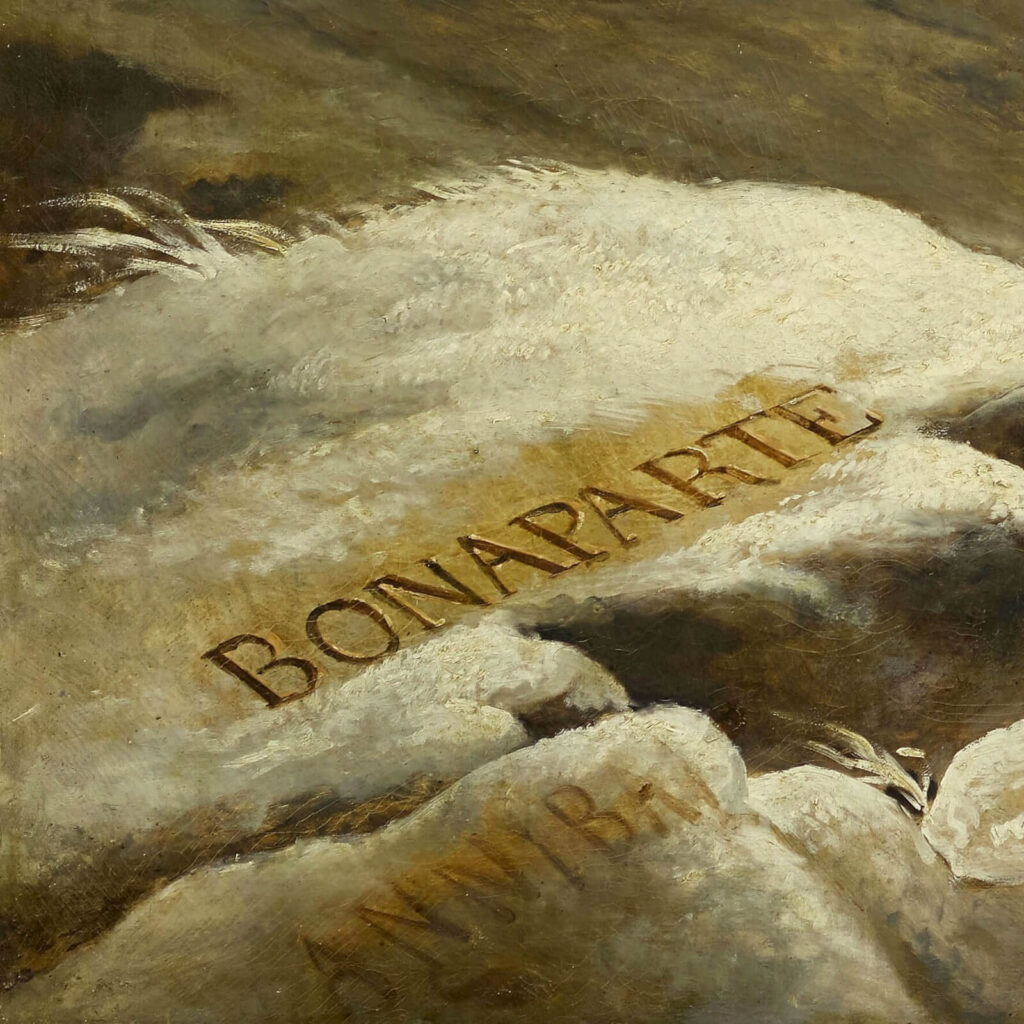

Through Jacques-Louis David’s painting, Napoleon’s image has become the poster image of a Romantic war hero. The painting’s dramatic landscape, clothing, and pose increase the punch and power to Napoleon’s legacy. David links Bonaparte with other great leaders who crossed the Alps by engraving “BONAPARTE,” “HANNIBAL” and “KAROLVS MAGNVS IMP” (Charlemagne) in the foreground. The overall impression is the product of a master public relations expert. The enthusiasm for this image is still present today by the many museums and stores throughout France that sell souvenirs with this painting emblazoned upon them. The merchandise includes posters, postcards, paperweights, file folders, drink coasters, notebooks, biographical books, etc. The list is as extensive as is his legacy. Would David and Napoleon be amused to discover that their early 19th-century image has become an early 21st-century cult icon? Their art has become pop culture. Long live David! Long live Napoleon!

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Detail.

10,000 Years of Art, London, UK: Phaidon Press Limited, 2009.

Wendy Beckett and Patricia Wright, Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces, London, UK: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1999.

Bonaparte franchissant le mont Saint-Bernard, 20 mai 1800, Palace of Versailles Online Collection. Retrieved 11 Nov. 2023.

Victoria Charles, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, and Donald Wigal, 1000 Paintings of Genius, New York, NY, USA: Barnes & Noble Books, 2006.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Portrait de l’artiste, Louvre Online Collection. Retrieved 11 Nov. 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!