Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

The statue of Ramesses II is a masterpiece of ancient Egyptian sculpture that proclaims the royal majesty and prowess of Ramesses the Great.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy.

Ramesses II, known as Ramesses the Great, was one of the richest, most powerful, and longest reigning pharaohs of ancient Egypt. He ruled for 66 years from 1279 to 1213 BCE when historians believe that the average lifespan was 32 years. He increased his country’s wealth and territory, built numerous monuments like Abu Simbel, and created a strong royal image through countless portraits of himself. One such portrait sculpture, Ramesses II, is a masterpiece of his legacy and ancient Egyptian art.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy.

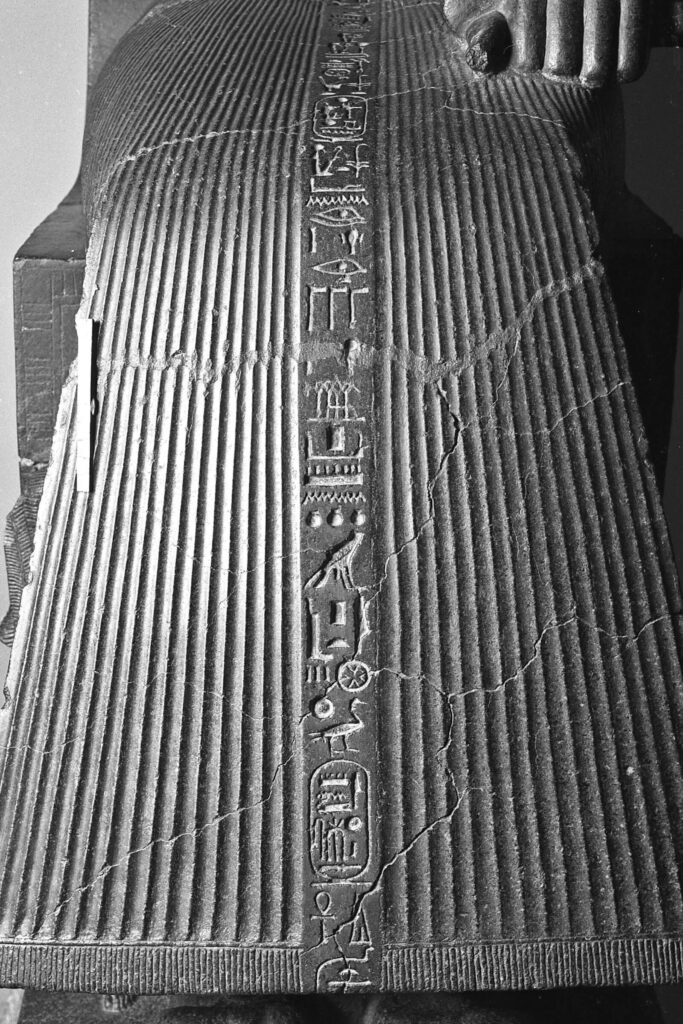

Ramesses II is a sculpture carved from a single solid block of granodiorite which is a coarse-grained igneous rock similar to granite. It is the same material used for the famous Rosetta Stone which was later created in 196 BCE. Ramesses II is an over life-sized statue measuring 196 cm tall, 105 cm deep and 70 cm wide. It presents the large seated pharaoh wearing a royal headdress and a broad necklace, holding a scepter in his right hand, while wearing a ceremonial tunic and thick sandals.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy.

Ramesses II is not a sinuous moving sculpture to be viewed in the round. It is to be appreciated from four rigid viewpoints: a frontal view, two profiles, and a back view. The fixed perspectives and inflexible posture imply the hard, firm, and immovable authority of pharaoh. Ramesses II controls the viewer’s gaze and therefore reminds the viewer that the king is in control of the viewer and of his kingdom. The stature exudes royal authority.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy.

The royal figure wears a royal headdress known as the khepresh. It is colloquially known as the Blue Crown or War Crown as it signifies the wearer’s military prowess. Ramesses II was one of the last successful warrior-kings of Egypt by leading over 15 military campaigns. He also expanded Egypt’s territory of control and influence to portions of the Levant which is now occupied by the modern countries of Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

The khepresh is also surmounted by the uraeus, or rearing cobra, that symbolizes the goddess Wadjet. She reflects the divinely appointed sovereignty of the king. Therefore, the khepresh reminds the viewer of the king’s military glory and royal authority.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

Below the khepresh is the statue’s face. The stylistic similarities between this face and Ramesses II’s father, Seti I, place this statue in the early years of Ramesses II’s reign. Some historians even proposed the idea that the statue was originally Seti I, and that Ramesses II usurped and rededicated the statue into his image. However, there are no signs of recarving, such as a smaller head. Therefore, the statue is original to Ramesses II despite the heavy artistic influences of his father’s previous reign. The face presents a young, confident, and idealized image of the king.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

Below the face sits a necklace or broad collar composed of six bands and a tassel edge. Many examples of broad collars survive from ancient Egypt, especially from the Middle and New Kingdoms, therefore the colors of the Ramesses II’s can be conjectured. Praised and frequented materials would be gold, carnelian, turquoise, and lapis lazuli. It would be a spectacularly colorful and rich necklace that Ramesses II would wear. Sadly, none of Ramesses II’s personal broad collars have survived into modern times.

Broad Collar of Senebtisi, Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty, ca. 1850–1775 BCE, carnelian, faience, gold, and turquoise, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

In the right hand of the king is a scepter. It is the heka or crook that symbolizes royal authority. One of the most famous examples ever discovered was inside the tomb of Tutankhamun. It gives a glimpse into how the statue’s heka would have appeared in real life when held by Ramesses II. It would have been a beautiful combination of alternating bands of gold and lapis lazuli.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

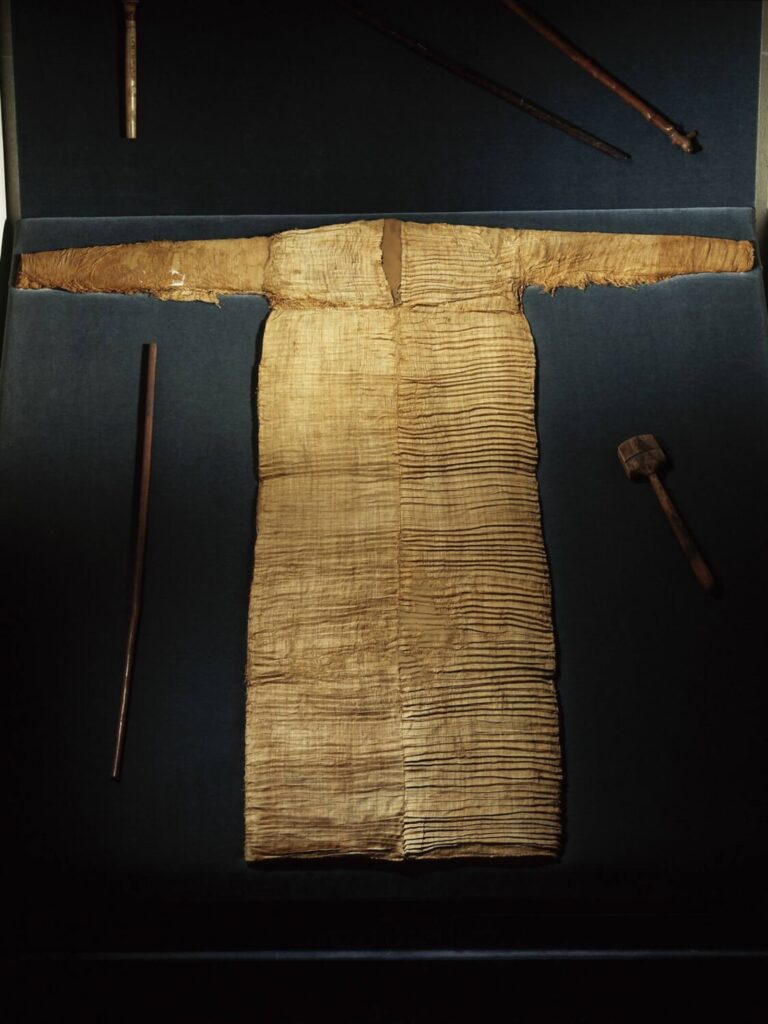

Cladding the entire body of the statue is a ceremonial tunic. It is a transparent pleated garment probably made of linen. It flares decoratively on the statue’s right arm which holds the heka. It is a form-fitted tunic that highlights the king’s svelte body, especially his wide shoulders, firm chest, thick arms, and flat stomach. Ramesses II is presented as a disciplined strong man who trains and works his body. He does not have the soft sensuality of the Amarna Period during the previous 18th Dynasty. His body is a return to long-held traditional values of strong kings in ancient Egypt. However, the full-body tunic is a new technique introduced during the New Kingdom because in the previous Old and Middle Kingdoms, strong kings were bare-chested with short kilts. Therefore, Ramesses II is returning to previous strong man attitudes with a newer interpretation of revealing his strong body through thin fabric.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

Tunic, Middle Kingdom, 11th–13th Dynasty, ca. 2033–1862 BCE, linen, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.

The statue wears a pair of thick sandals on its feet. They are probably made of leather or papyrus reed.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

Under the king’s sandals are the Nine Bows which are nine oblong ovals that symbolize the nine enemies of Egypt. For example, Nubians and Lybians were common and frequent enemies of ancient Egypt. The statue is proclaiming that the king is trampling his enemies with his authority.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

Pair of Sandals, Second Intermediate Period – New Kingdom, 17th–18th Dynasty, ca. 1580–1479 BCE, papyrus reed, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

The legs of the large statue are flanked by two diminutive figures: a young male on the viewer’s left and an adult female on the viewer’s right. The adult woman is Queen Nefertari, the king’s chief wife. She wears a headdress in the style of the Goddess Hathor with its two horns framing a solar disk and two long feathers. Queen Nefertari was deeply beloved by Ramesses II, and some historians say that it was a rare royal love-match much like millennia later with British Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Nefertari’s presence dates the statue to the first 30 years of Ramesses II’s reign because she died during his 30th reigning year in 1249 BCE. Nefertari’s image implies her beloved presence in the king’s life.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

To the viewer’s left is a young male who is the king’s son and heir, Amunherkhepeshef. His presence states the fertility of Ramesses II and Nefertari, and the secured lineage of the dynasty. Ancient Egyptian history is frequently troubled by succession unrest. Therefore, securing a legitimate heir was paramount for the peaceful transition from one pharaoh to the next. Ramesses II allegedly produced over 100 children throughout his life with multiple royal wives, therefore his lineage was well secured.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

Sadly, Amunherkhepeshef did not outlive Ramesses II because he died in the 25th reigning year in 1254 BCE. Another son, Merneptah, was eventually to take the throne. Amunherkhepeshef’s presence further dates the statue to be created no later than 1254 BCE. Hence, 1279–1254 BCE is the statue’s established creation time frame.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

Ramesses II is now located in the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy. However, its original location was at the Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex in Thebes (modern Luxor), Egypt. It was probably erected as a thank-you to the God Amun for some act of godly benevolence. Perhaps the pharaoh had just won a war, finished a grand project, or survived a deadly illness? Sadly, the statue’s hieroglyphics do not state the reason for the dedication. However, for the past three millennia this statue continues to captivate the imagination of those fortunate enough to have seen it.

Ramesses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279–1254 BCE, granodiorite, Temple of Amun, Karnak Temple Complex, Thebes (Luxor), Egypt, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Detail.

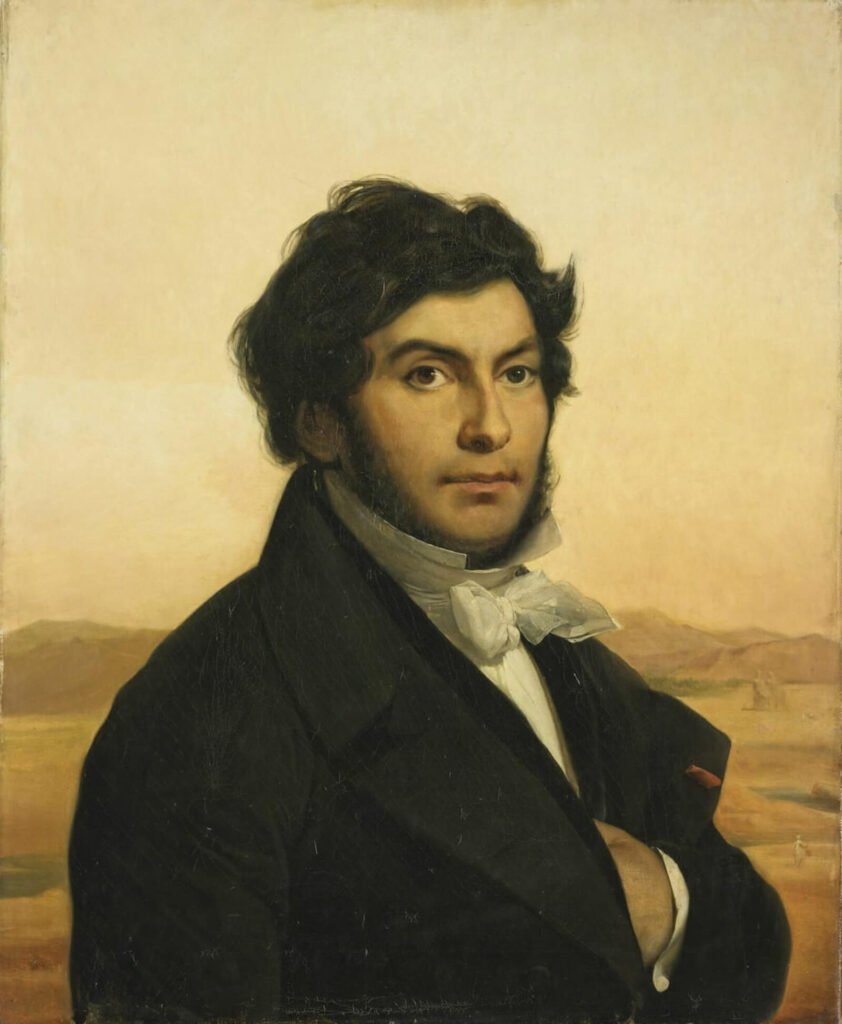

When Jean-François Champollion, the famous French decipherer of the Rosetta Stone, viewed Ramesses II in Turin in 1824 he was compelled to describe it in a letter. He wrote:

“the beauty and the admirable perfection of this colossal figure… for six whole months I have seen it every day, and always I have the impression of seeing it for the first time. The head is divine, the feet and hands are admirable, the body is voluptuous; I call it the Egyptian Apollo of the Belvedere… in short, I am in love with it.”

Letter, 1824

Léon Cogniet, Portrait of Jean-François Champollion, ca 1834, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.

“Broad Collar of Senebtisi.” Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Retrieved 28 January 2024

Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Málek, Jaromír. Egypt: 4000 Years of Art. London, UK: Phaidon Press Limited, 2003.

“Pair of Sandals.” Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Retrieved 28 January 2024

“Portrait of Jean-François Champollion.” Collection. Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

Smith, W. Stevenson, and William Kelly Simpson. Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale University Press, 1998.

“Statue of Ramesses II.” Collection. Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

“Tunique.” Collection. Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!