The (Real) History of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving brings families together to share rich meals featuring turkey, stuffing, and seasonal décor like pumpkins and warm autumn colors.

Errika Gerakiti 28 November 2024

18 November 2024 min Read

Since the beginning of human history, drawing and creating diagrams has been essential. They were the easiest and most useful form of communication and recording. The main subject matter was, of course, everyday life – animals and the human body itself. Over the years, having such a marvelous machine provoked interest in illustrating it. And with increasing precision. It was shown not only from the outside but a special focus was placed on seeing the inside. And what about the function and malfunction of its parts? Anatomy and art were indissolubly born together. They also developed side by side through the centuries in the form of medical illustration.

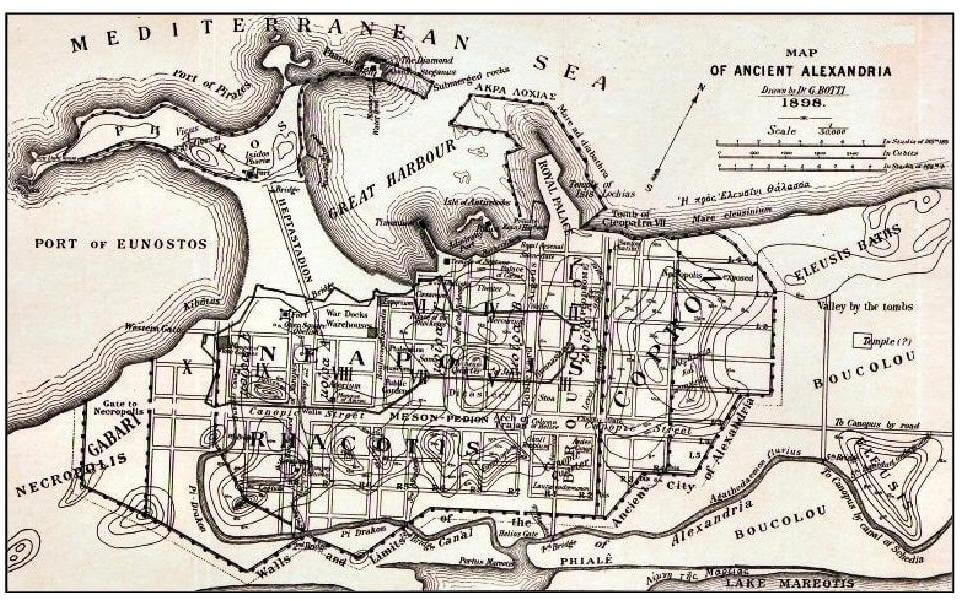

In the tombs of Ancient Egypt, explorers found a number of images of medical-anatomical interest in sculptured relief (25th century BCE). Aristotle also played a role in visual medicine. He created what were probably the first anatomical illustrations based on the dissection (or cutting up) of animals. However, actual medical illustration – created with a precise medical purpose – first appeared in Alexandria. Around the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, Alexandria was a brilliant center of learning. Here, the Greek physicians Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos began to carry out a methodical dissection of human bodies, an activity which had been forbidden until then. Sometimes, they used drawings to describe their observations and discoveries.

After the Greek period, the Roman Empire rose in splendor. The Romans’ practical attitude was also evident in science. As a matter of fact, they tried to consolidate previous knowledge instead of creating new ideas.

Galen of Pergamum was without doubt the most important physician of the period (200 CE). He reflected the Roman attitude by combining all the previous medical ideas together, thus creating an all-embracing medical theory.

By that time human dissection was, once again, considered a controversial and restricted practice. Therefore, Galen derived most of his observations from animal dissections (pigs and monkeys) and only partly by studying the wounds of gladiators. He wrote volumes about anatomy and physiology and his writing dominated European medicine up to the 16th century. But his books were not so realistic. They were mainly descriptive and it is not certain if they included illustrations.

In medieval Europe, the traditional “Wound Man” was almost the only anatomical theme. Some attempts were made to record the human body objectively through carrying out forbidden dissections. However, nothing was done systematically.

The Renaissance was a turning point. Artists rediscovered the classical art of ancient Greece and Rome. At the same time, two elements were fundamental. Firstly, the acceptance of dissection permitted the renewal of anatomical studies. Secondly, the invention of printing allowed easy duplication of illustrations and their integration into text pages, instead of having to be on separate plates.

These elements stimulated artists to deepen their knowledge and to represent the human body accurately. However, like the rest of Renaissance art, medical illustration was a mixture of realism and idealism. This was the period in which the artist and the anatomist were not always the same person. In other words, the physician dissected, and some artists became freelance medical illustrators. They often did this out of necessity (looking at and representing cadavers was not a comfortable task). However, in most instances, they gradually became more interested and disciplined themselves to this unusual job. In fact, they also gained a new understanding of the world.

Through collaboration, the production of excellent illustrations flourished, merging artistic skill and scientific background. Extremely graceful anatomical figures in dramatic poses emerged in detailed landscapes, sometimes with classical architecture. The medical illustration was an “excuse” for showing a renewed passion for representing the human body.

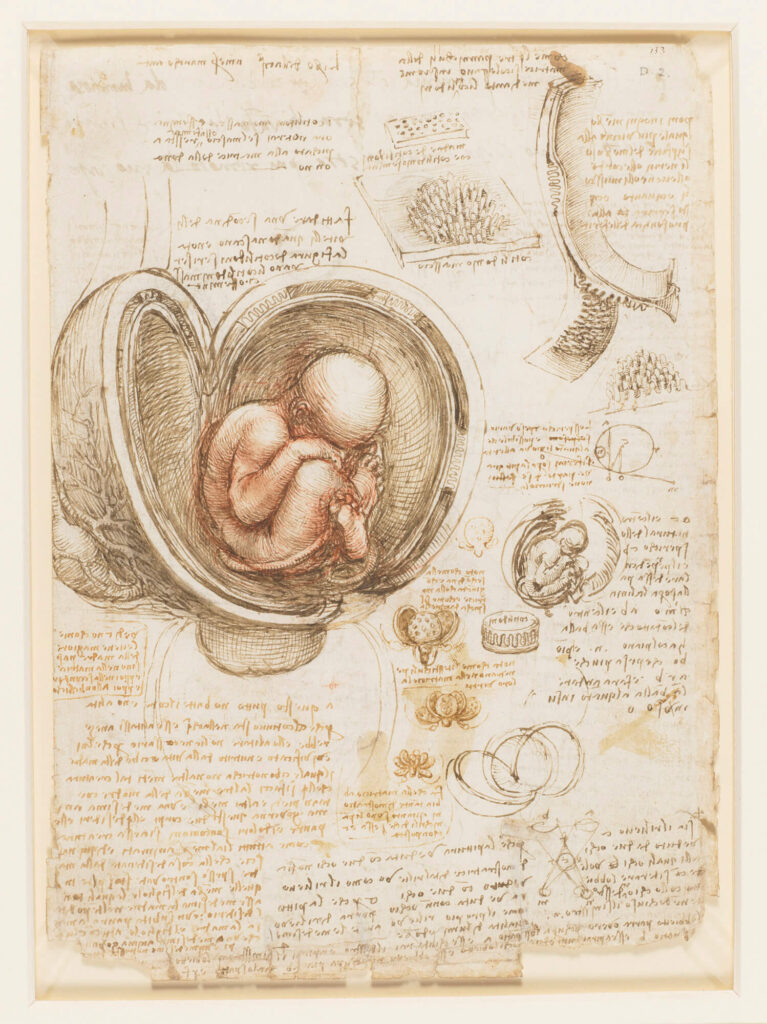

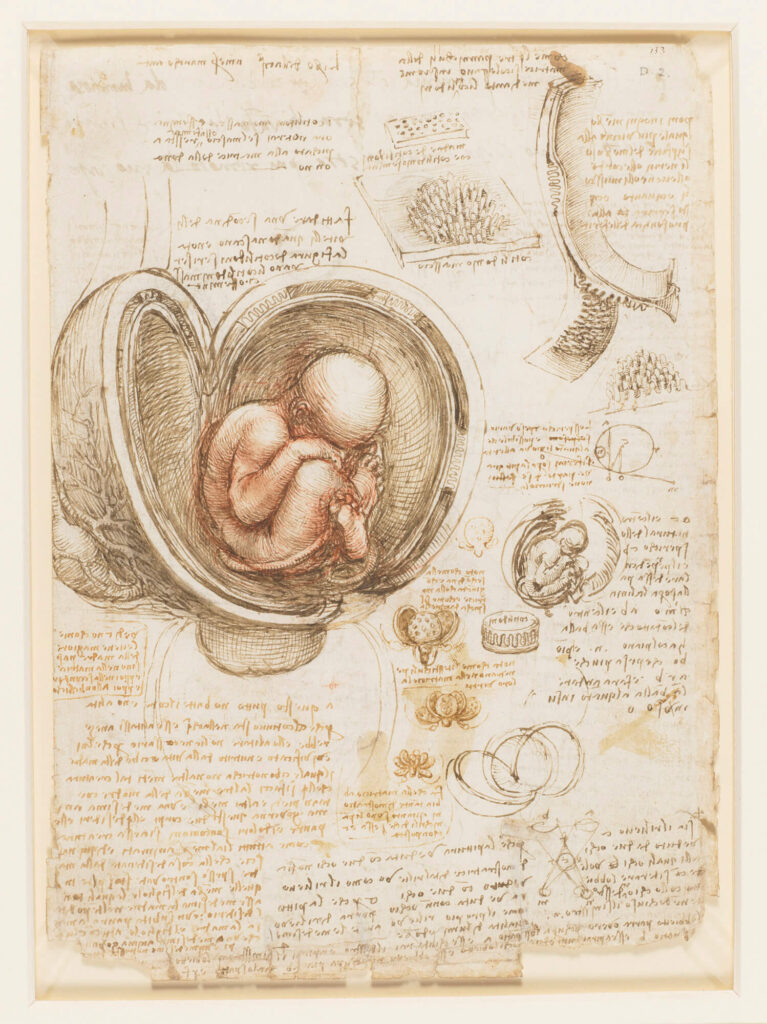

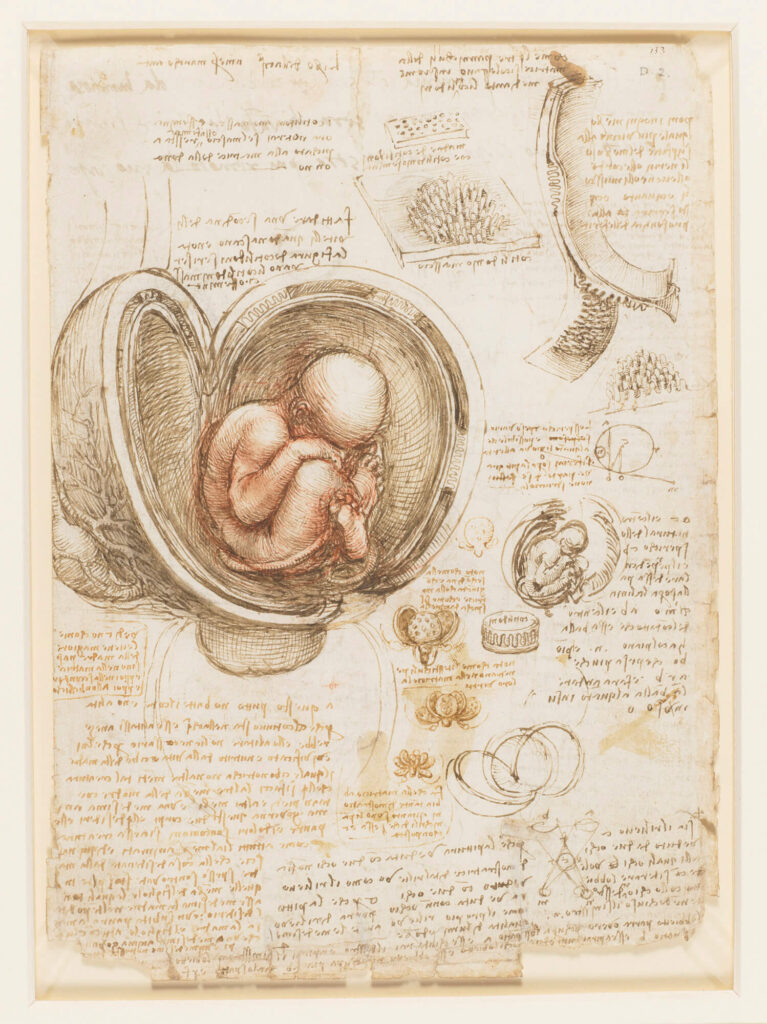

In this context, Leonardo is an exception. Among his endless list of interests, Leonardo also had a particular curiosity for the marvelous piece of engineering that is the human body.

His anatomical illustrations came from his personal dissection of over 30 bodies, which he performed between 1489 and 1513. He often wrote about his natural disgust at having to work among corpses. Yet, for the love of science, he created a brand new global anatomical portfolio. This was possible thanks both to his skill and to his self-taught education. He drew plans and sections as in architecture and recorded details, as in engineering. At the same time, his work showed the same realistic and accurate technique we see in his art. He created over 7000 sheets of sketches, but the originals were never published. Only 200 sheets appeared again in the 19th century and came into the public domain, being published in facsimile. Nevertheless, his contemporaries probably knew his anatomical research well. His work also influenced the field of medical illustration for the following decades.

In the 1530s, the University of Padua became one of the centers of scientific advances. Here, a talented Belgian young physician called Andreas Vesalius earned the degree of Doctor of Medicine. The following day he obtained the role of Professor of Surgical Anatomy.

He was something of a revolutionary personality. The contemporary method of teaching anatomy left him completely unsatisfied. He thought that students should observe real bodies, not study “classical texts”. Moreover, he was sure that Galen’s bases were largely inaccurate. In fact, he came to the conviction that his great predecessor had never dissected a human body.

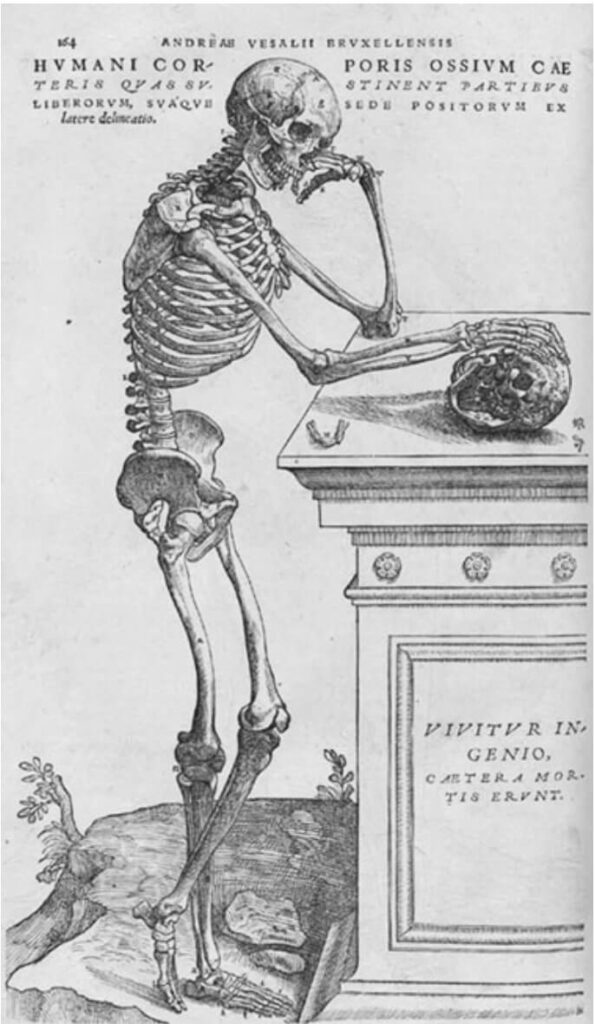

Vesalius began his own dissections, and his students asked him to draw what he found. After devising some initial anatomical tables, in 1543 he published his masterpiece, the Librorum De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Librum Septum (Seven Books on the Structure of the Human Body). This work contained anatomic illustrations of great artistic quality. It was the first atlas of human anatomy in history.

Vesalius himself said that the text was of secondary importance to the illustrations. The drawings were attributed to Jan Stephan van Calcar, a pupil of Titian. However, they are probably the work of a group of well-trained artists from Titian’s studio: Titian found anatomical illustration an exciting challenge. The artist’s role is clear for, while the images are anatomically precise, they have been artistically revised. The results are “polite” and far removed from the flesh and blood reality of dissection. Nonetheless, this work shows the first real collaboration of the practitioners of medicine and art – between the artist and the doctor.

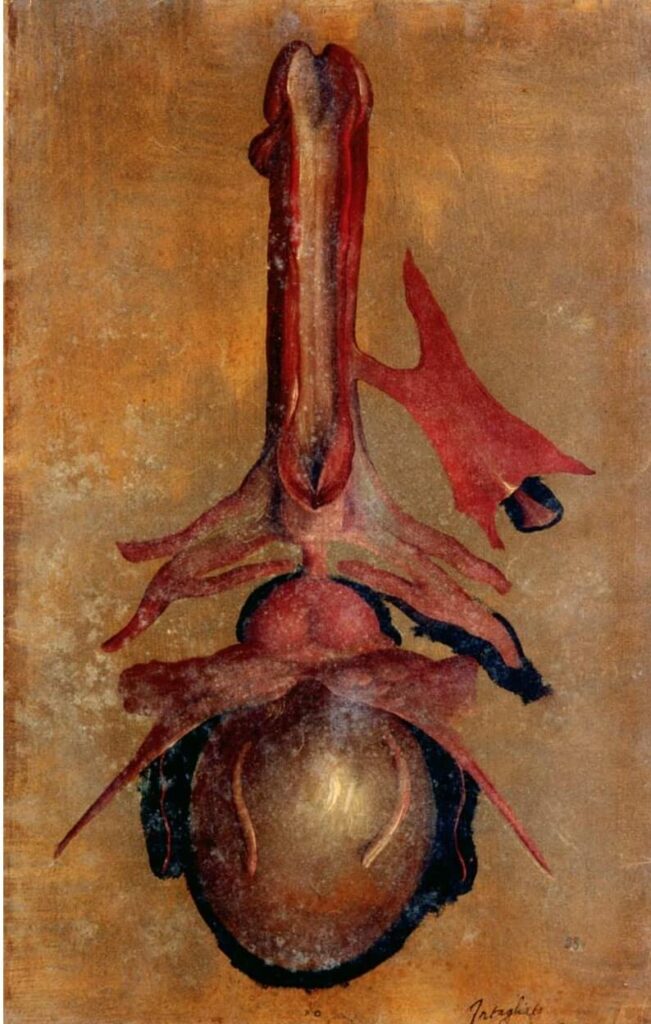

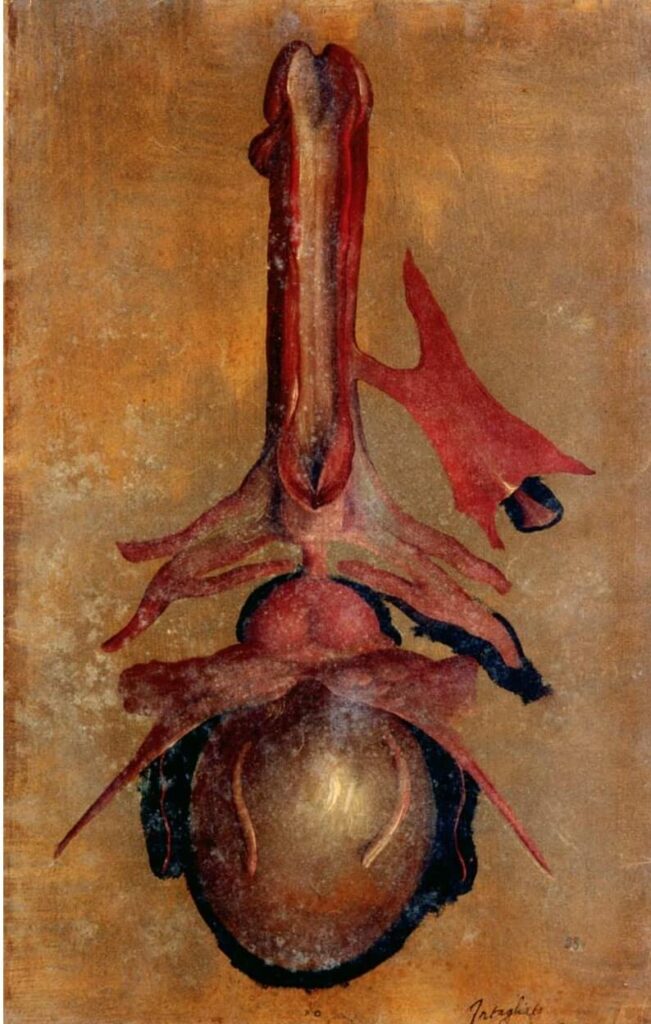

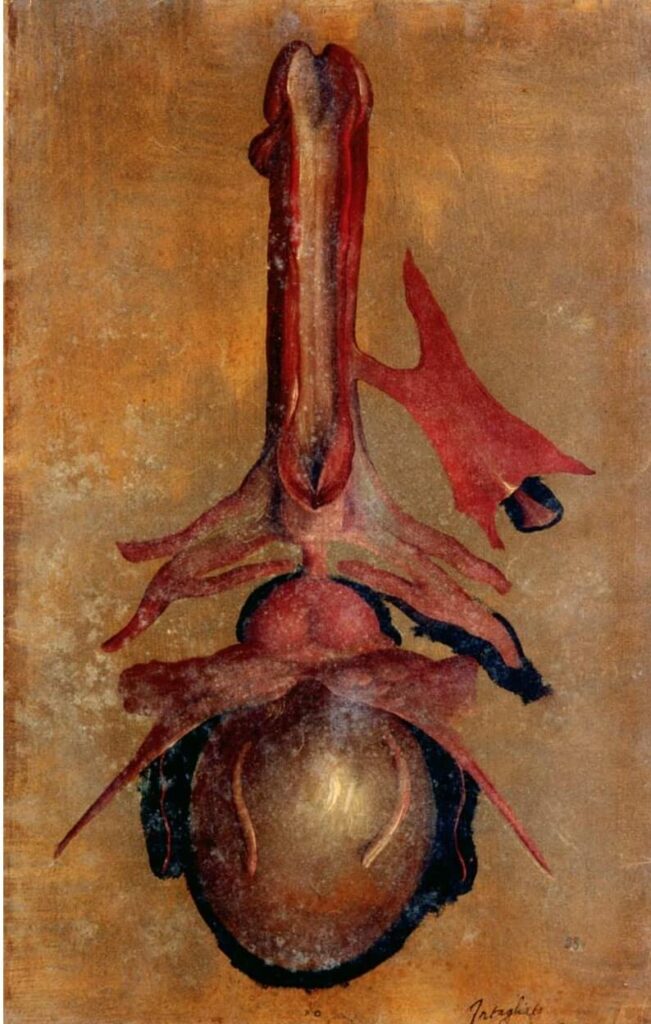

Hieronymus Fabricius ab Acquapendente was another revolutionary in the field of anatomic illustration. He was a known anatomist and surgeon and Professor of Anatomy at the University of Padua, like Vesalius. Acquapendente was the first to employ a strictly scientific approach to anatomical drawings. He was also a prolific publisher of anatomical treatises. In his work, there were no dancing cadavers, no animation or expressive faces, nor bodies like classical statues. His collection of anatomical illustrations is known as Tabulae Pictae. Its content lacks the artistic expression of previous works. It is full of natural-sized and natural-colored images. In addition, his figures focus on one structure at a time rather than displaying the entire body.

Fabricius provided a crucial turning point in the evolution of anatomical illustration. He and his artist-collaborators deviated from the earlier tendency of being more artistic than scientific.

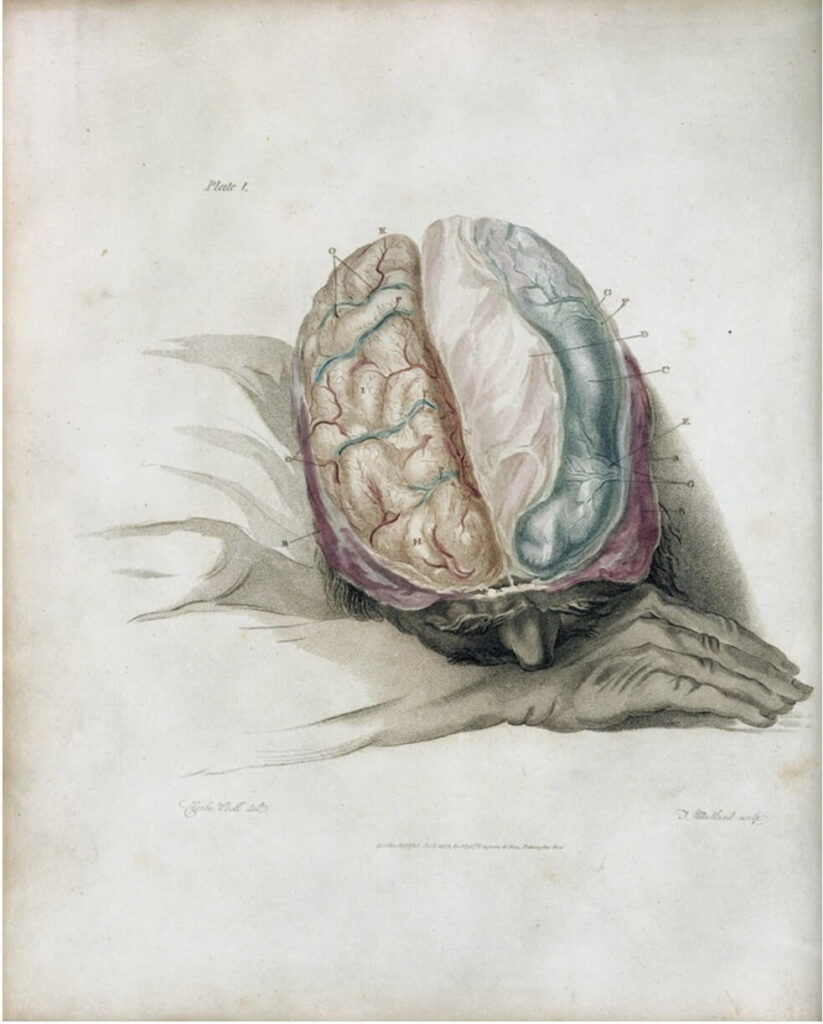

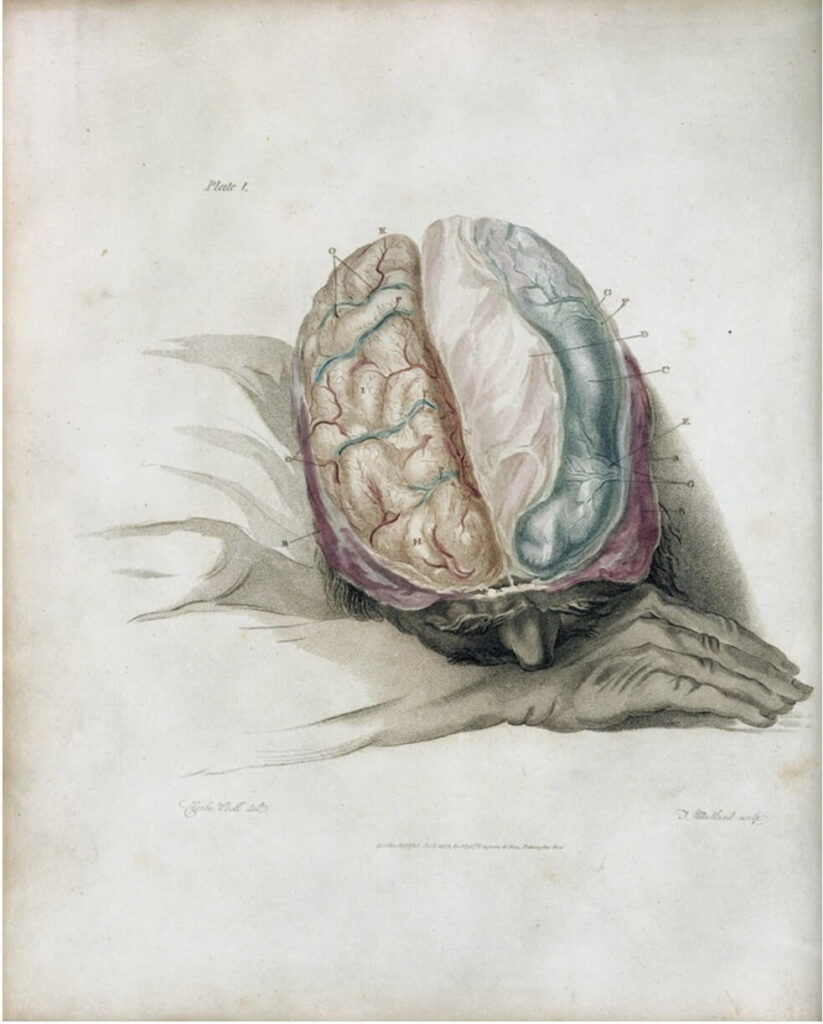

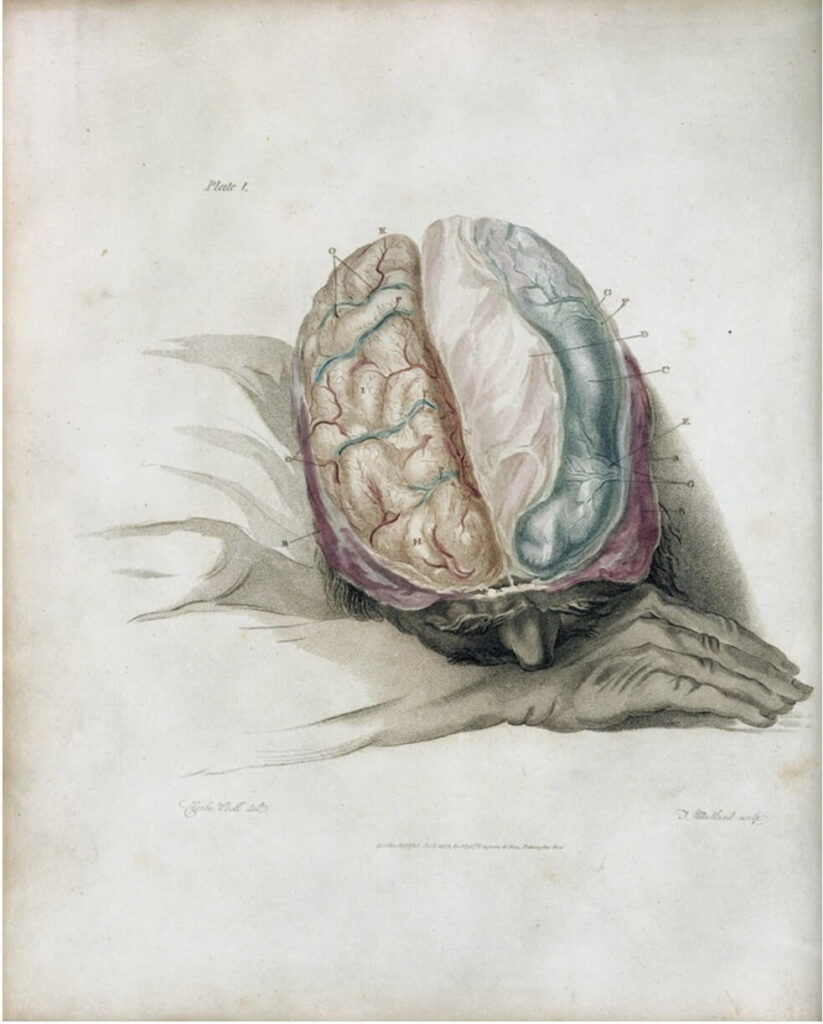

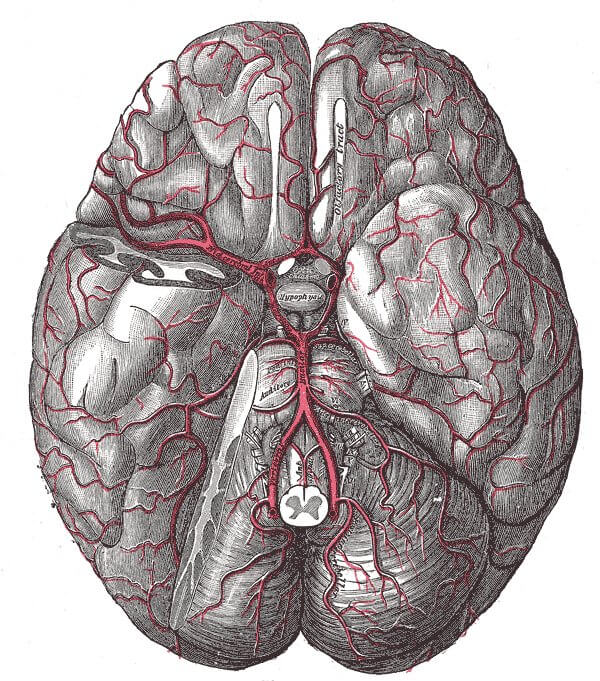

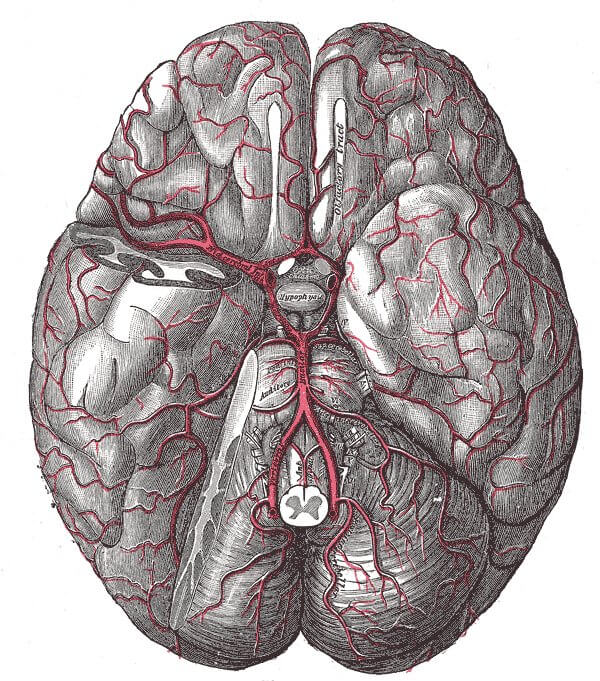

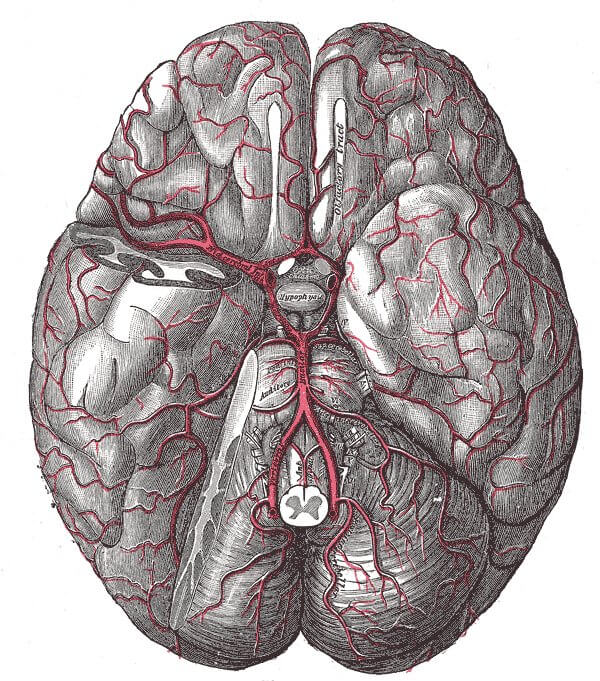

John Bell was a Scottish anatomist, surgeon, and Professor of Surgery in Edinburgh. In his work, he placed great stress on the fundamental role of anatomy in surgical practice. Indeed, he is known as the father of surgical anatomy. He prepared lectures on anatomy and surgical anatomy. Later, he published them under the title of Anatomy of the Human Body. This work contained illustrations that he had prepared himself, unlike the work of most of his predecessors.

His brother Sir Charles Bell carried forward his legacy. While still a student, Charles published his own first work A System of Dissection. He worked under the guidance of his brother and created excellent self-realized illustrations for the book. In 1807 Charles became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and commenced surgical practice. Despite this, he continued to publish anatomy texts and figures. He assisted his brother with his masterpiece while himself creating a series of illustrations. His main interests lay in the central and peripheral nervous systems. He made several significant contributions in the field of neuroanatomy.

When Charles moved to London he published his classic Essays on the anatomy and philosophy of expression. This work contained illustrations of dissections of the facial musculature, in different emotional expressions, linking individual muscles with specific emotions.

Charles also had two short periods of exposure to military surgery. This experience influenced his work and contributed to his legendary fame in anatomical sciences.

Another physician contributed to the evolution of anatomical sciences. Henry Gray, English anatomist and surgeon, was a lover of learning-through-dissection. His incredible review of human anatomy was the basis of his legendary work Anatomy: Descriptive and Surgical, first published in 1858. It contained 363 illustrations. These were prepared by his friend Henry Vandyke Carter, who was himself a demonstrator of anatomy.

To understand the value of this text, just think about this. Gray’s Anatomy is still the reference book on anatomy for the majority of medical students all over the world. This success is due in part to the precision of its illustrations. Again, as in previous decades, no graceful poses, exotic backgrounds or dramatic actions can be found. Just scientific description. What was new was the labeling. Images in contemporary anatomy books were usually proxy labeled. The reader had to look elsewhere for the key (usually a footnote). Carter’s illustrations, by contrast, unified name and structure thus enabling the reader’s eye to take in both at a glance.

Max Brödel was a young artist from Leipzig, Germany. In 1894 he arrived at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, United States as the result of an invitation to collaborate with a famous gynecologist. They were going to create an illustrated textbook.

Brödel did not have any formal medical training. Nevertheless, he was able to learn about concepts of anatomy, pathology, physiology, and surgery. He quickly became a brand new figure: a modern medical illustrator who was extremely able in blending art and medicine. His drawings had a classic beauty although his work was based on a scientific approach. He considered possible troubles for the printer and publisher. Above all, he was ready to devote his life to his work.

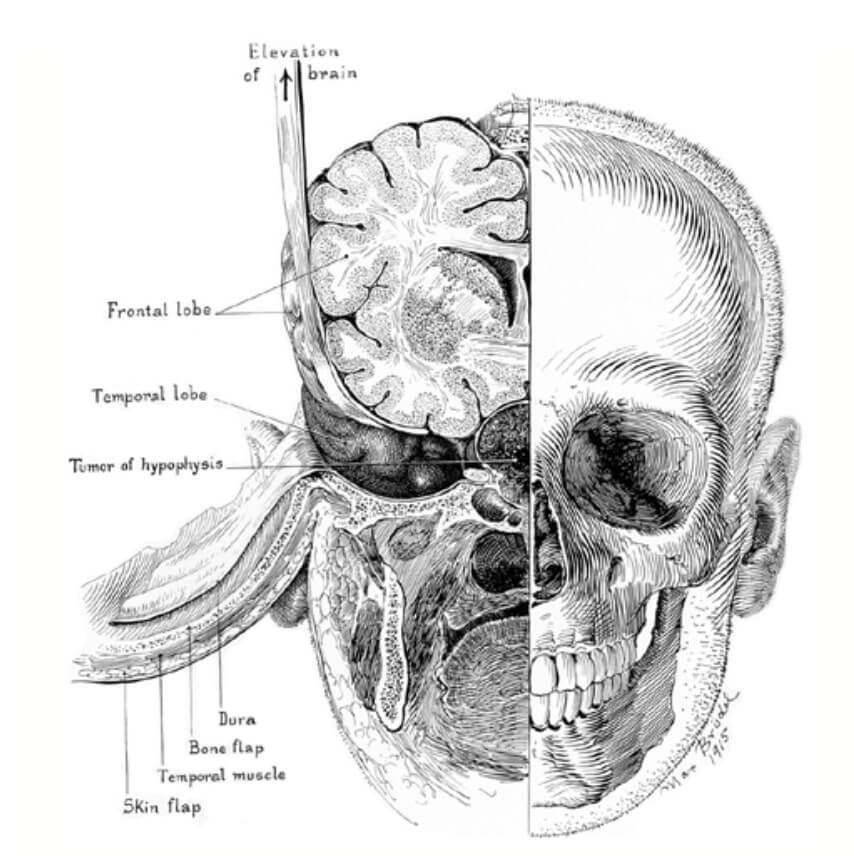

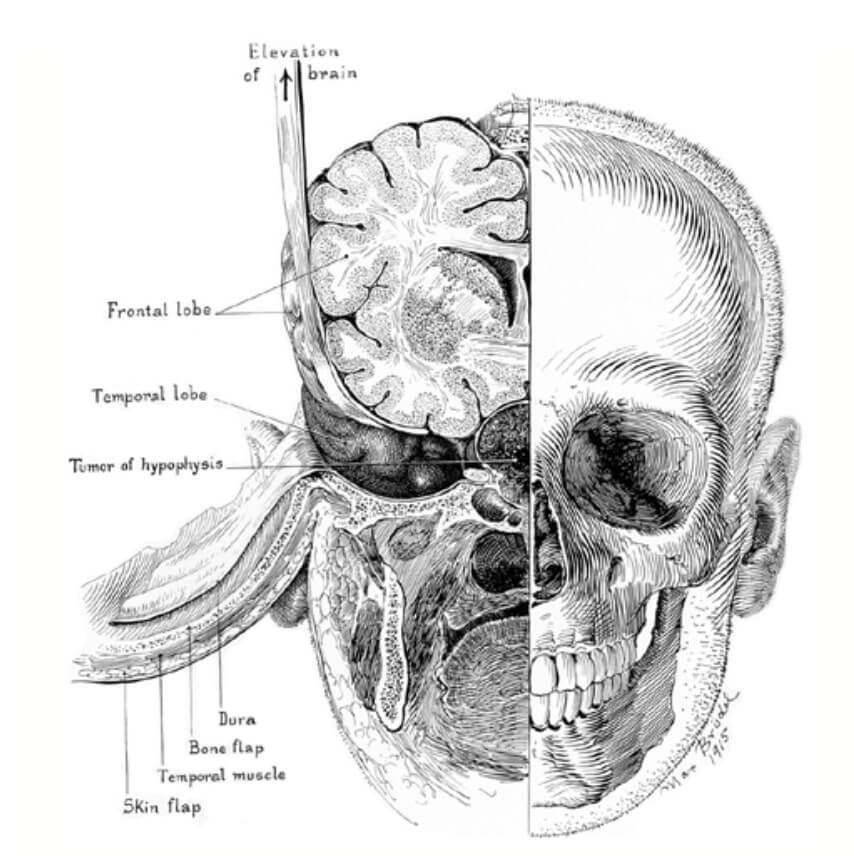

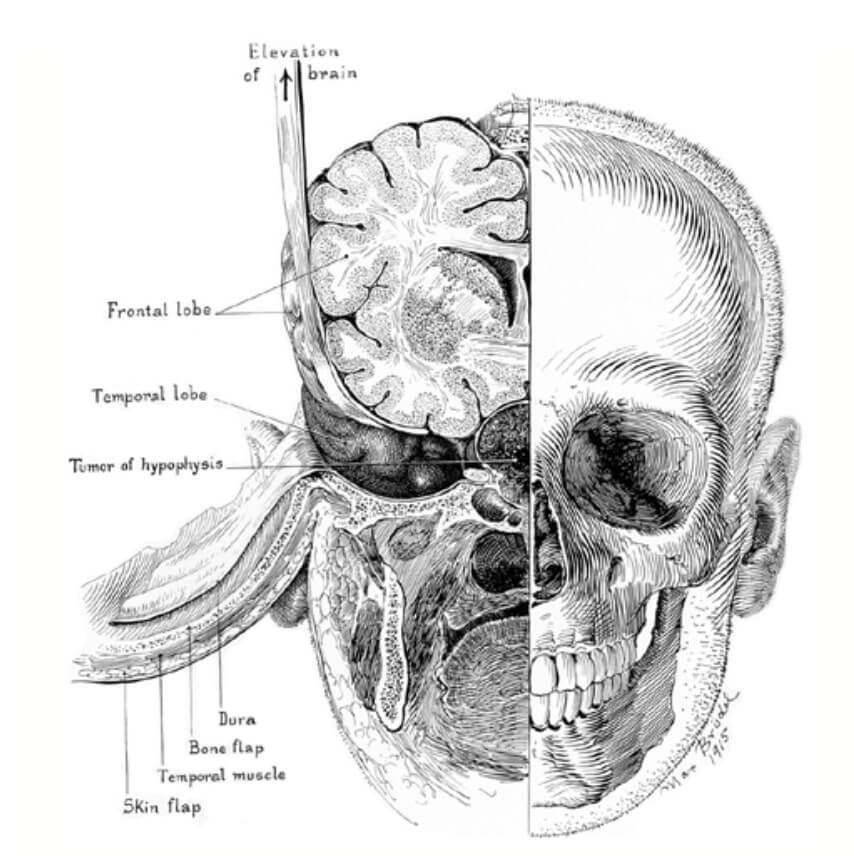

He introduced innovative art media, methods and techniques. His half-tone drawings, for example, reproduced the reality of a photograph. But in a better way. The camera couldn’t think and select like a human mind… sorry, a human hand. As a result, Brödel created timeless illustrations which are still indispensable to surgeons today.

Brödel is considered by many to be the father of modern medical illustration. In 1911 he obtained the title of Director of the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. It was the first academic department of its kind in the world. This unique event in medicine and art history laid the foundations for the formal education of the professional medical illustrator. Thanks to Brödel, this job now stands on its own. The medical illustrator is both a scientist and an artist, but not uniquely one or the other.

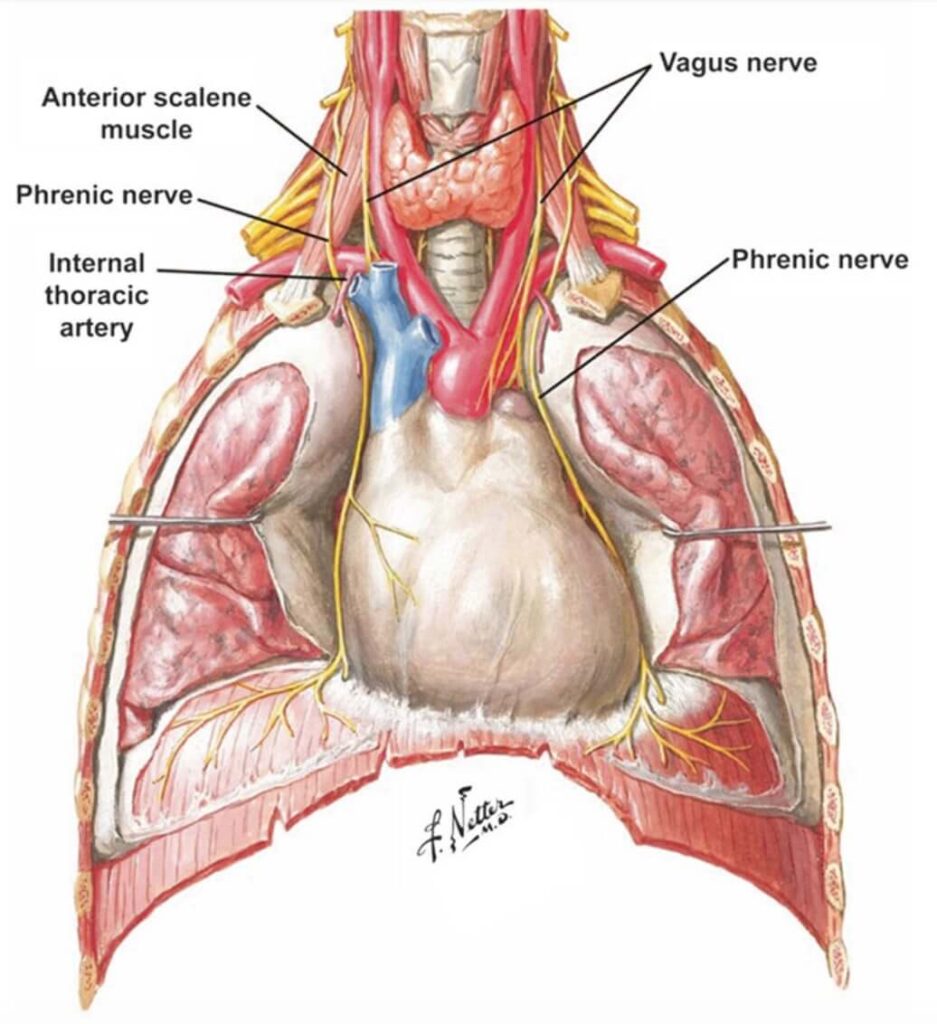

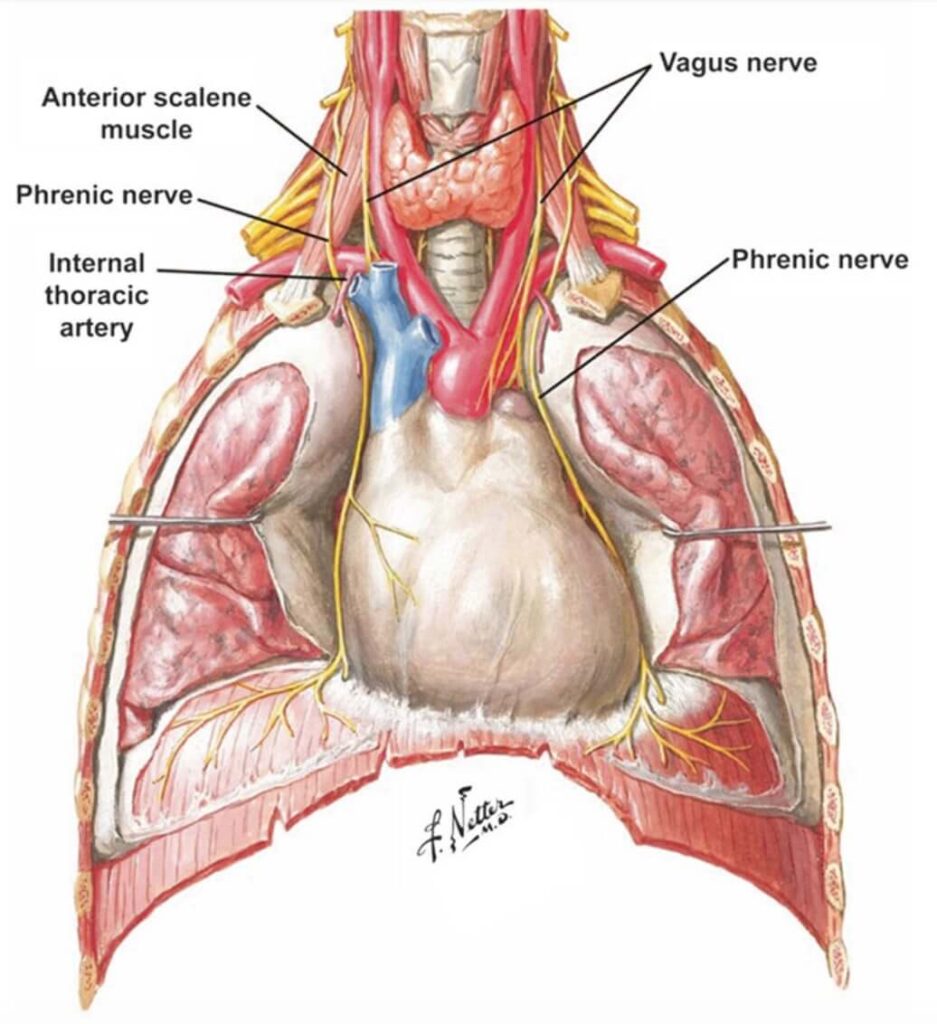

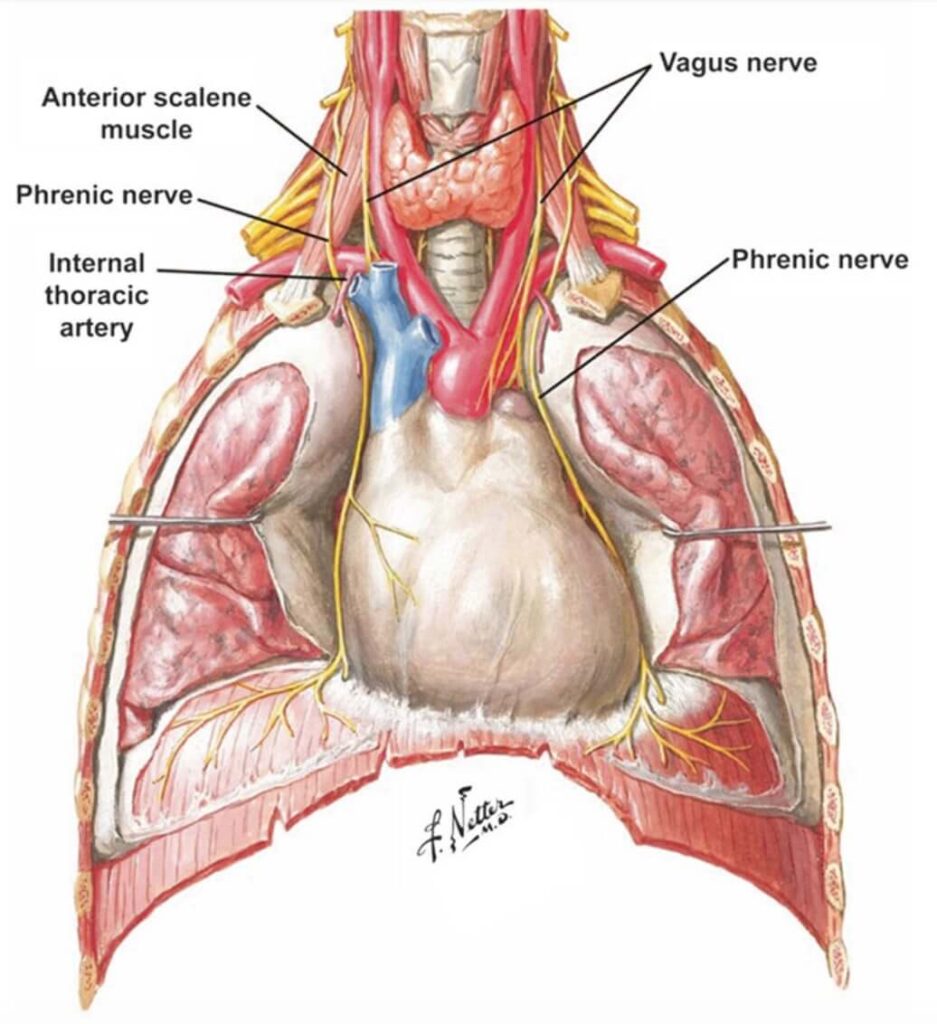

Frank H. Netter was an American surgeon who had always wanted to be an artist. In the first years of medical practice, Netter did medical artwork to supplement his income. However, he soon realized that medical illustration was his real dream job. He believed very strongly that medical illustration would only be of value if it explained a medical concept.

His book of over 4000 illustrations became popular immediately. It led initially to his first comprehensive collection, The CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations (1948). Next came the widely-known Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy. This atlas was probably his crowning achievement. It rapidly became one of the most widely used atlases of anatomy in medical schools all over the world. It is still in use today. Contemporary illustrators also routinely use Netter’s illustrations as references in order to create anatomical artworks with the help of advanced software.

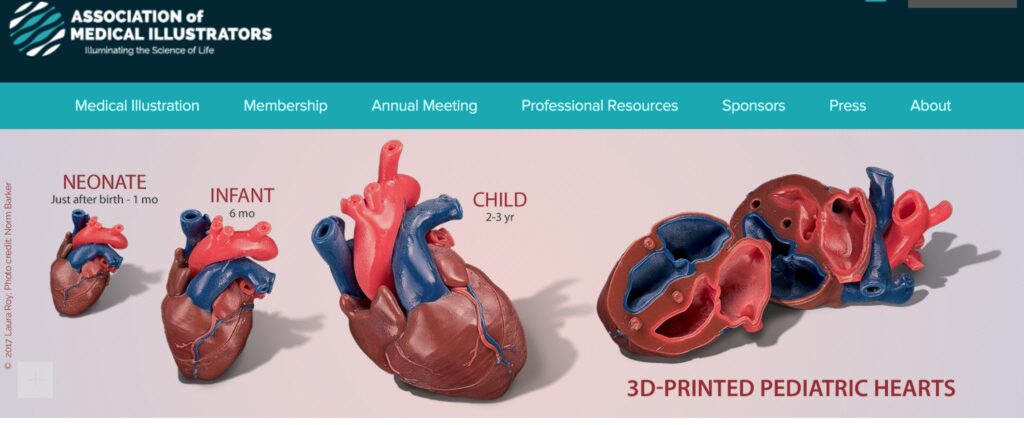

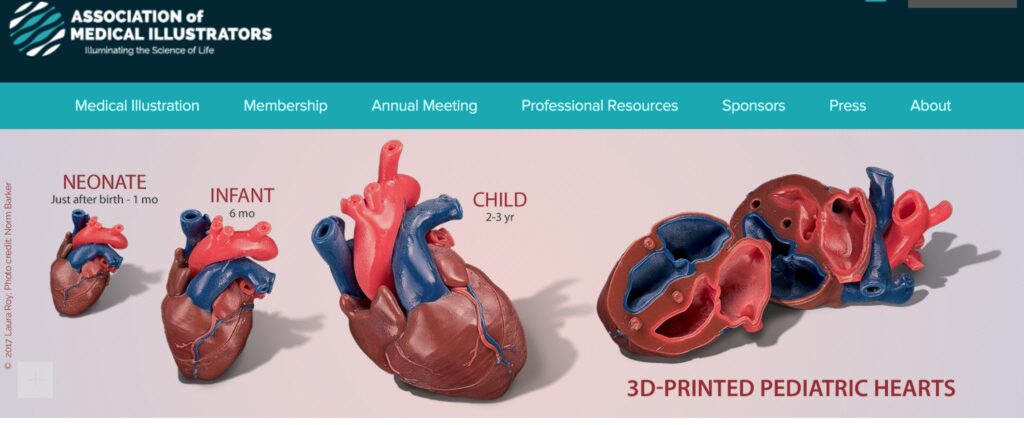

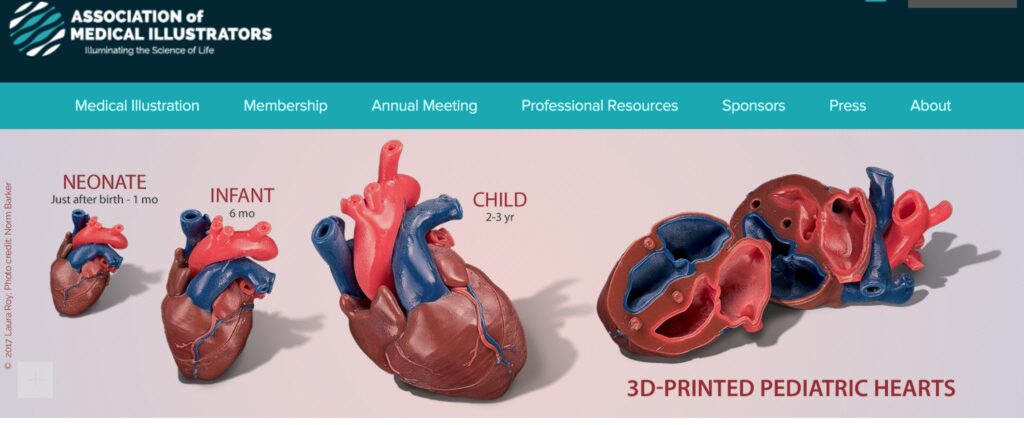

Now medical illustration has become a profession in its own right. An Association of Medical Illustrators was founded and a number of schools for the education of medical illustrators have been set up since that established by Brödel.

Medical imaging like computed tomography (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as photography, may seem more useful and accurate than illustrations. That’s not true. In fact, the role of illustration remains fundamental to the teaching and learning of medicine and allied subjects. Illustrations can focus on details. For example, using a sort of “augmented reality”, using unnatural colors to stress some points, or selecting different depths, unlike a genuine photograph.

Nowadays anatomical illustration also uses technological tools, in particular software technology. A new generation of medical images is being created in innovative formats. But the focus always remains on scientific education and, of course, artistic beauty.

Sanjib Kumar Ghosh, Evolution of Illustrations in Anatomy: A Study from the Classical Period in Europe to Modern Times, 2014, Anat Sci Educ 8: 175–188.

GJ Heuer, Surgical experiences with an intracranial approach to chiasmal lesions, Arch Surg 1:368–381, 1920.

Martin Kemp, Style and non-style in anatomical illustration: From Renaissance Humanism to Henry Gray, 2010, J Anat 216, pp. 192-208.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!