5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

10 October 2024 min Read

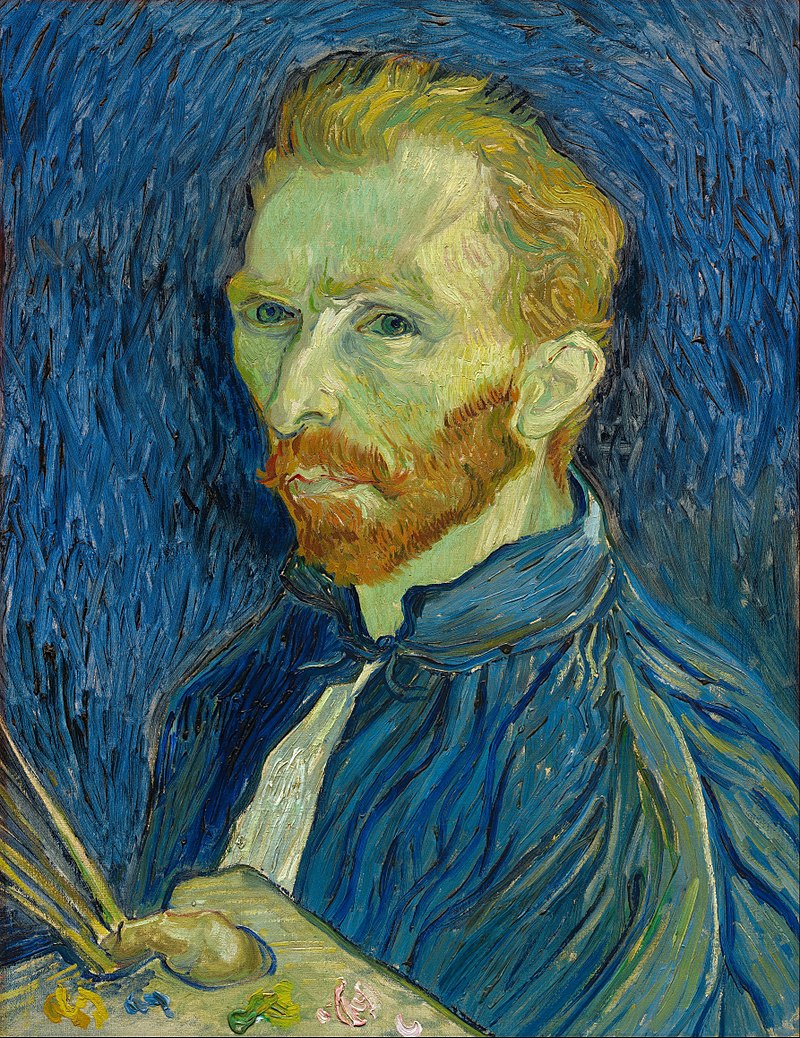

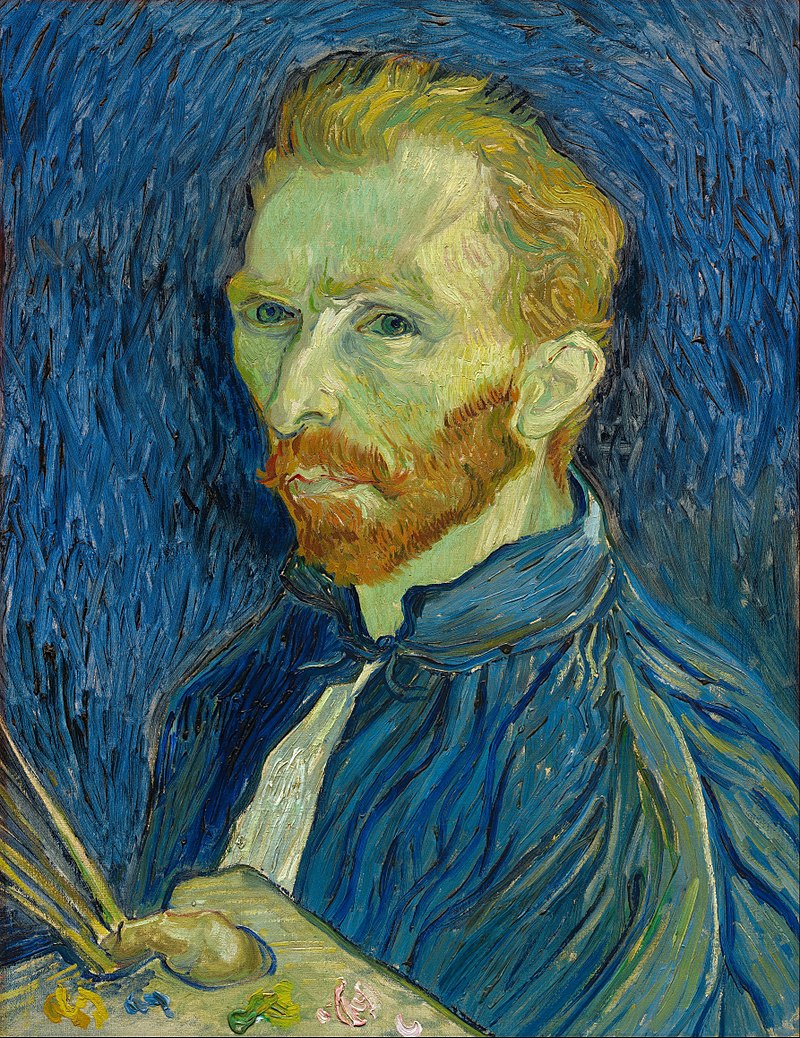

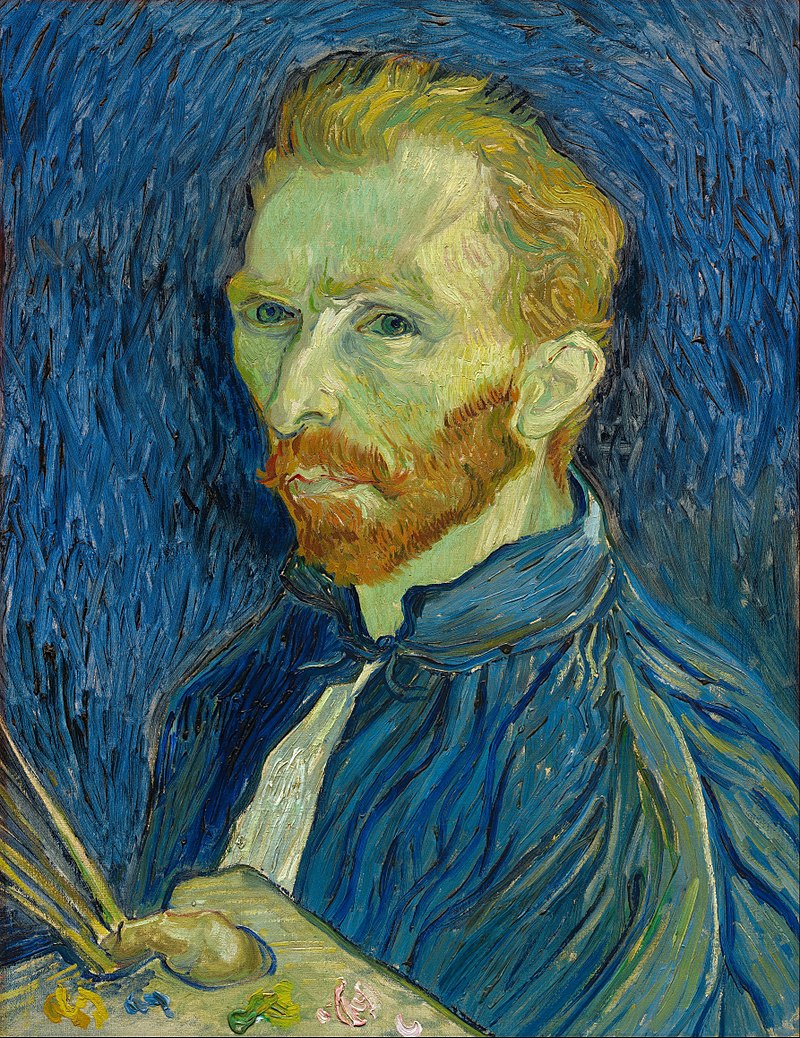

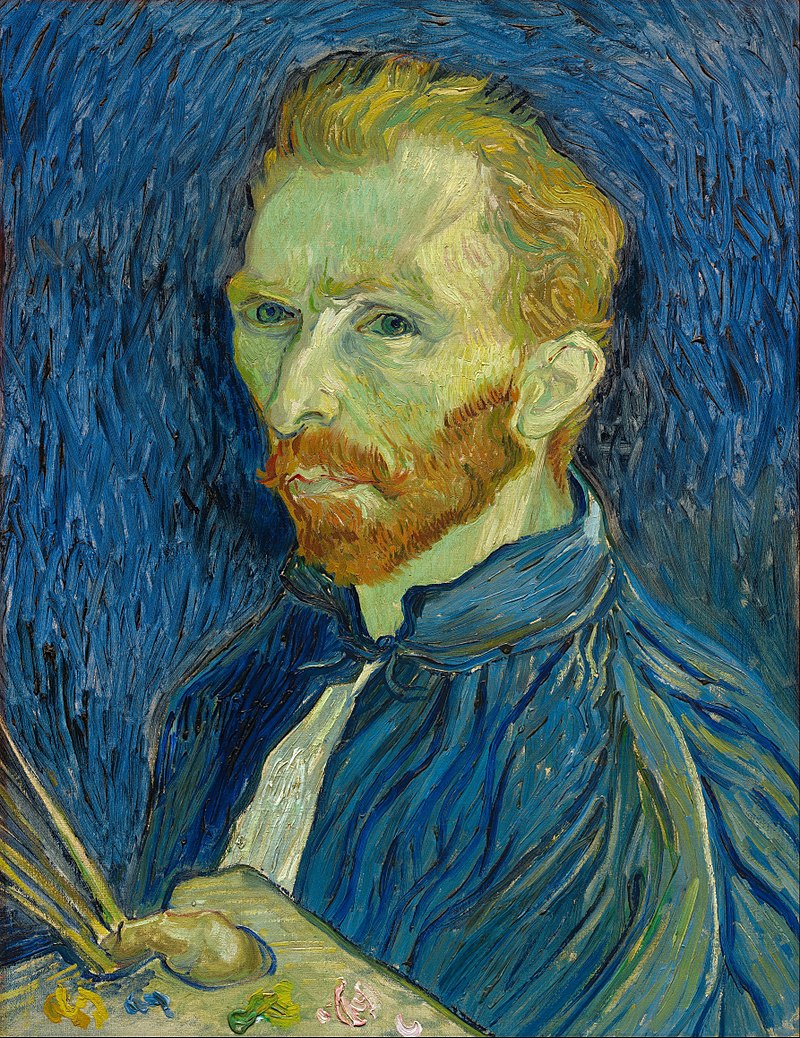

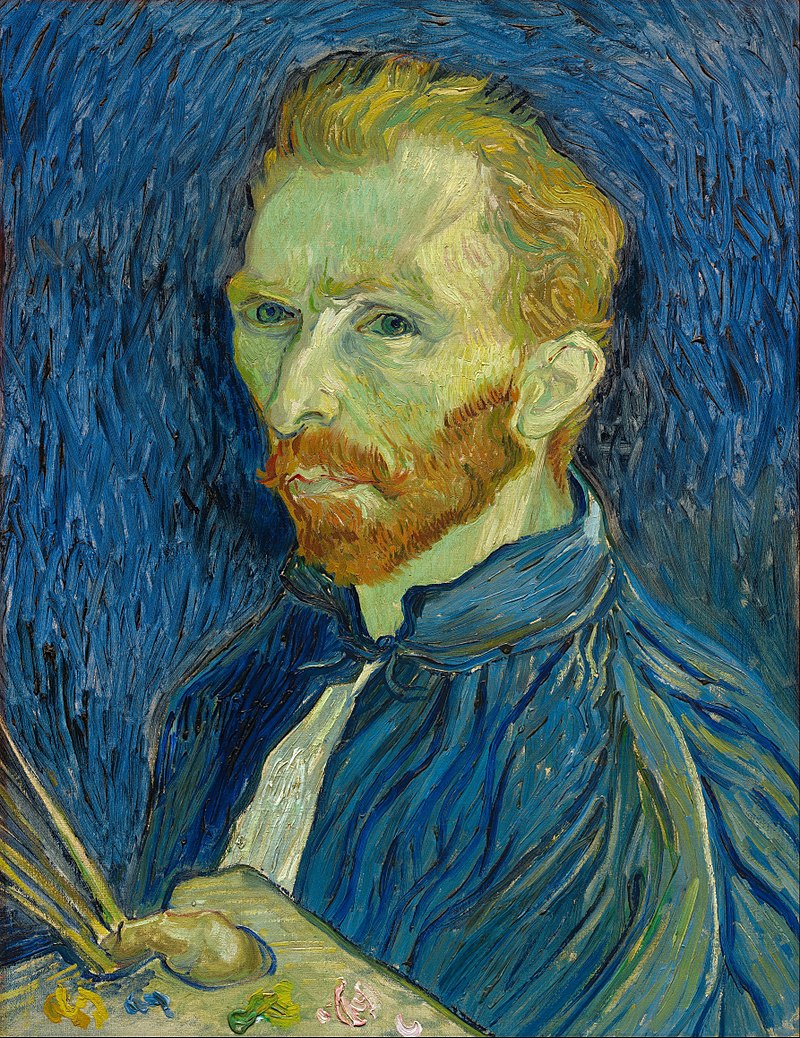

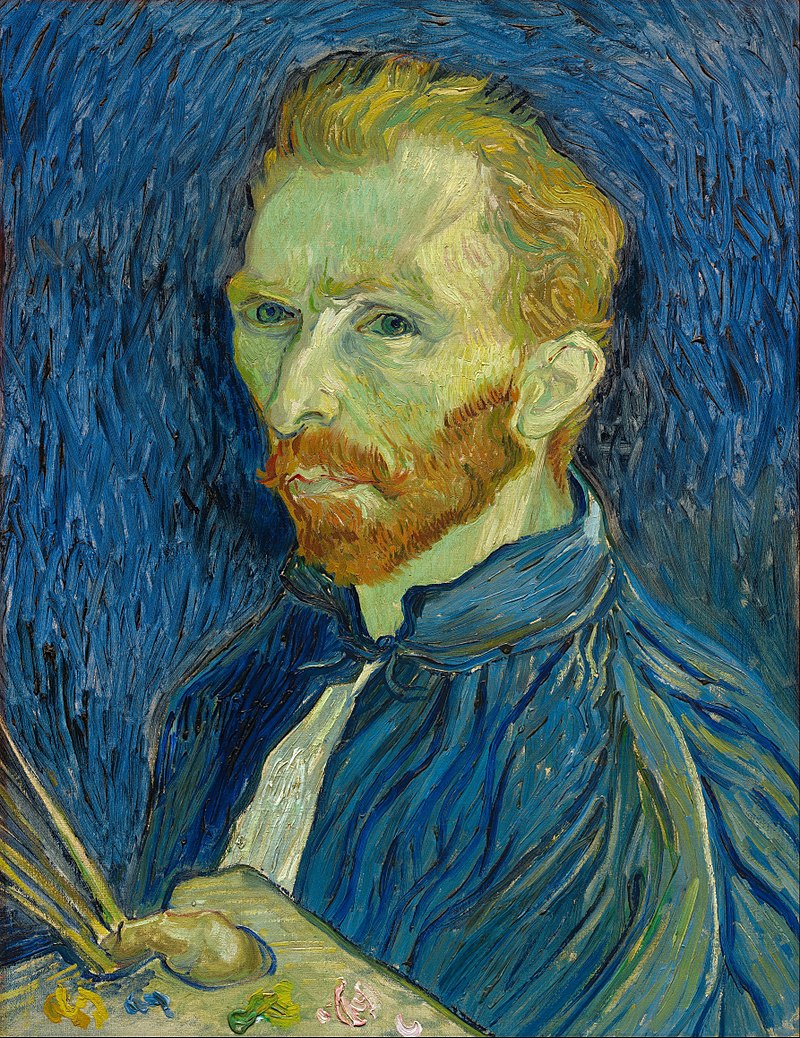

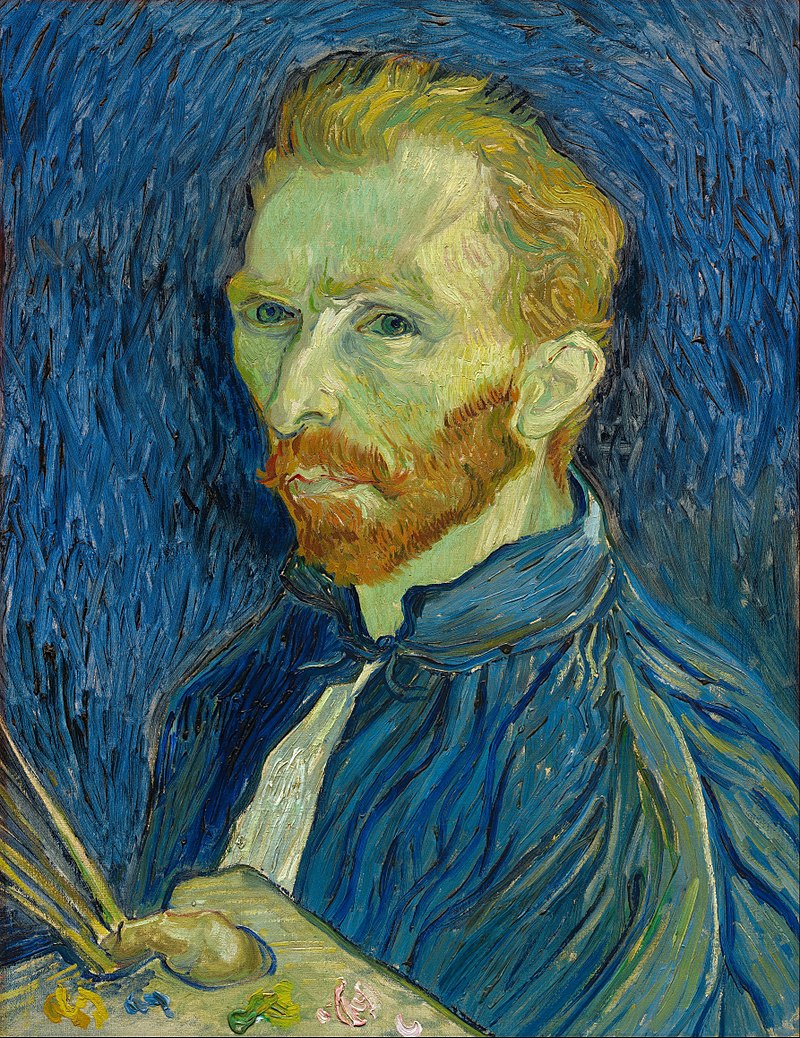

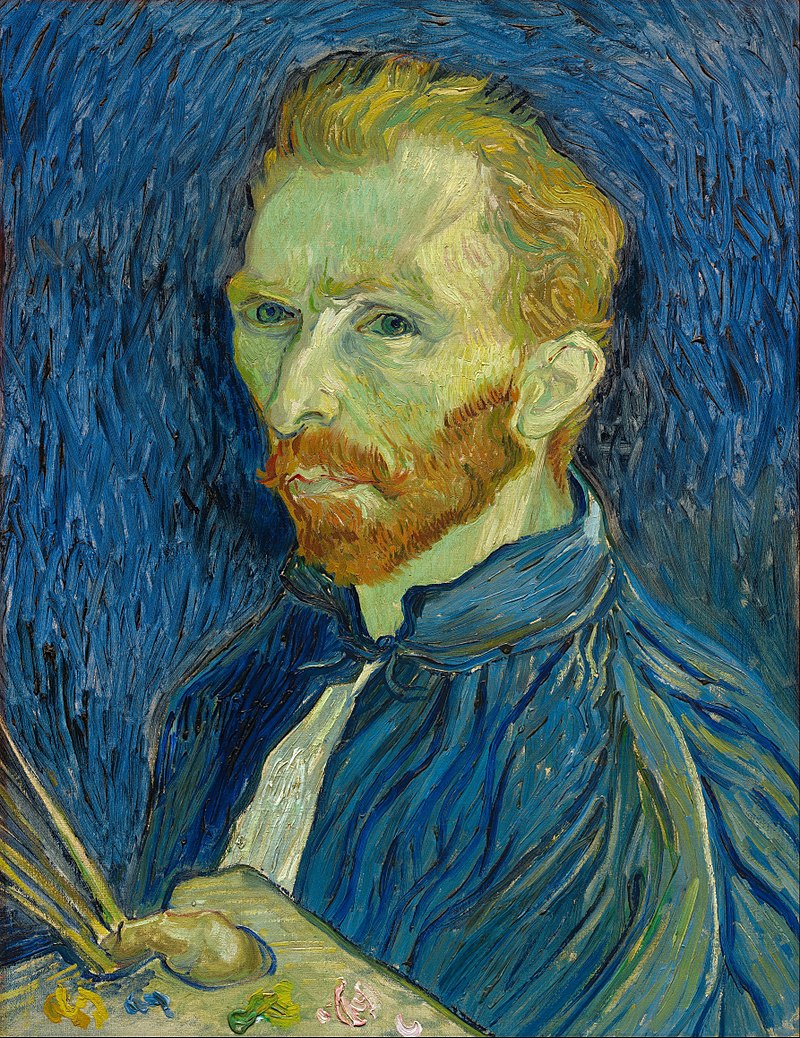

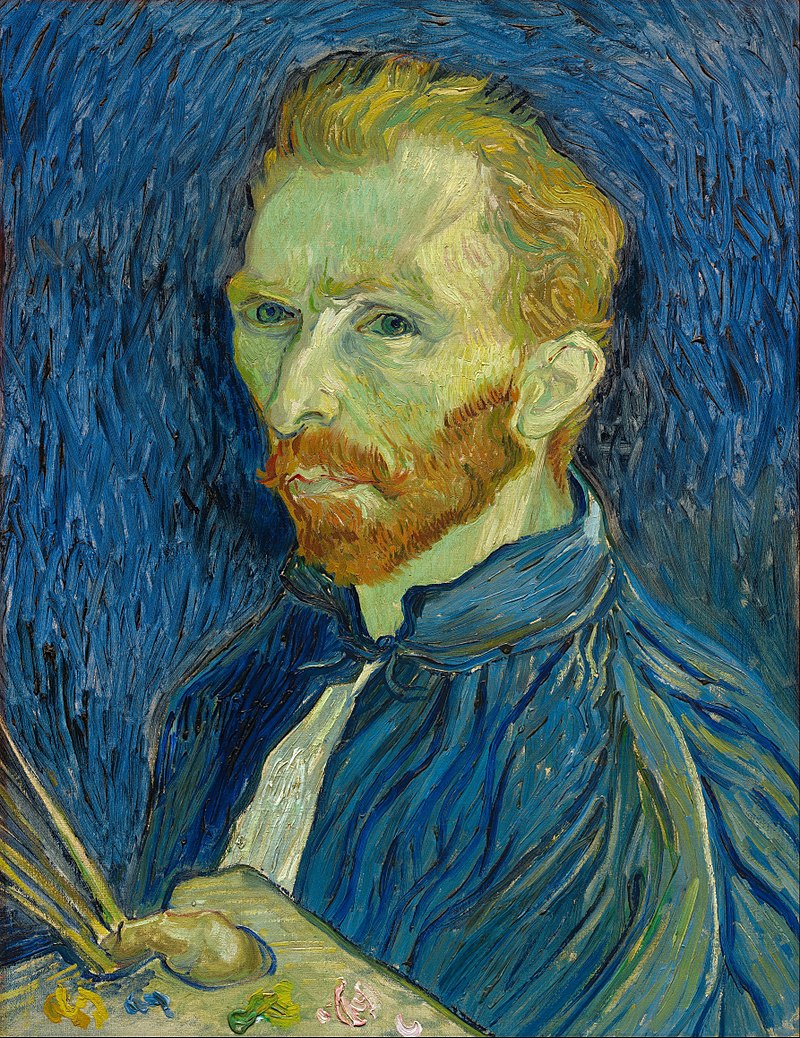

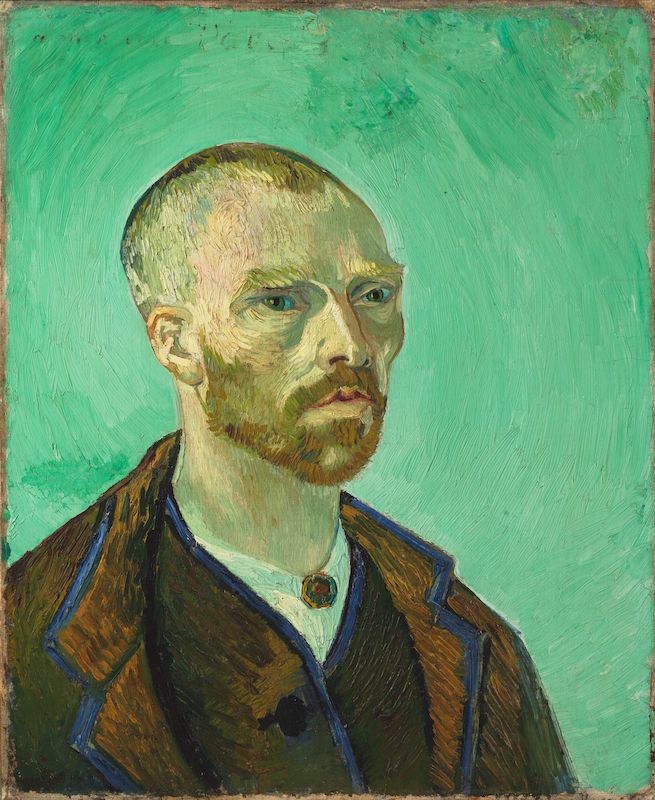

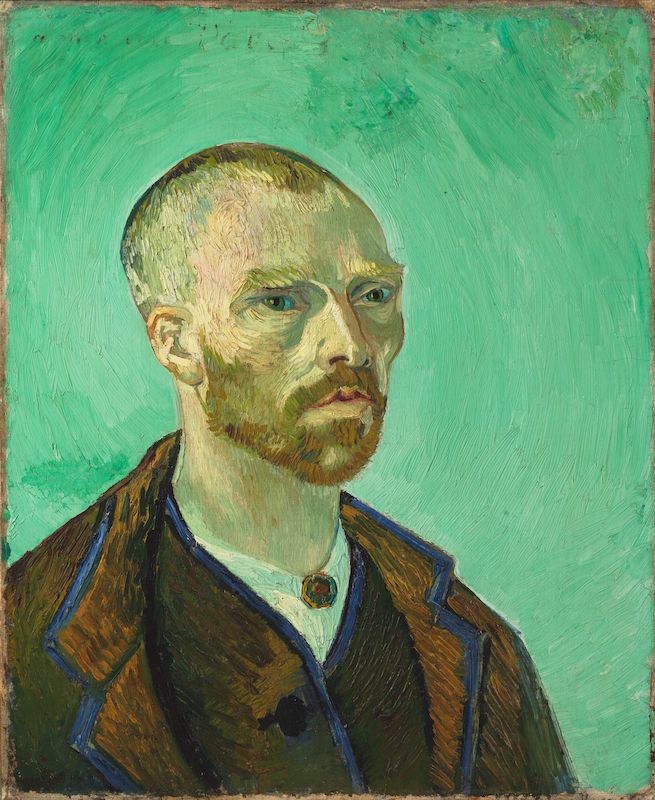

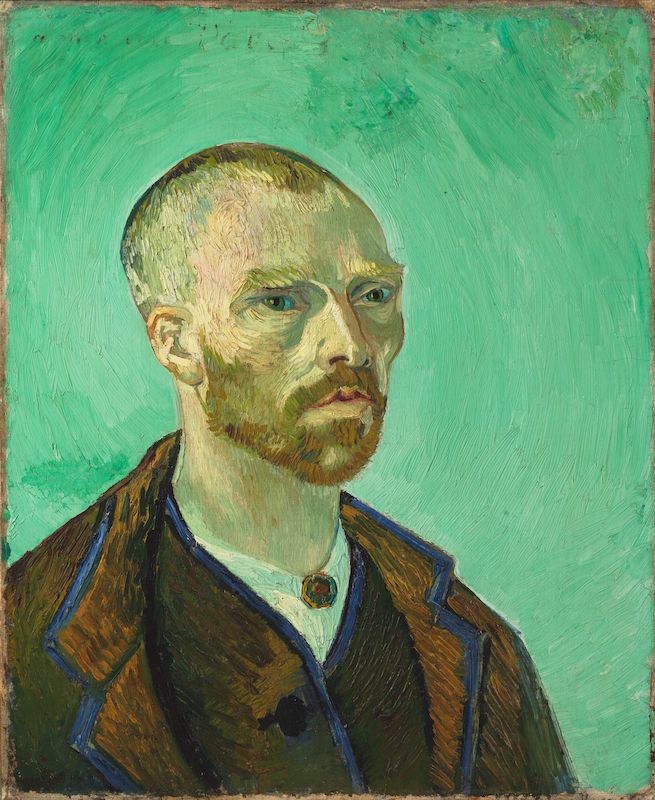

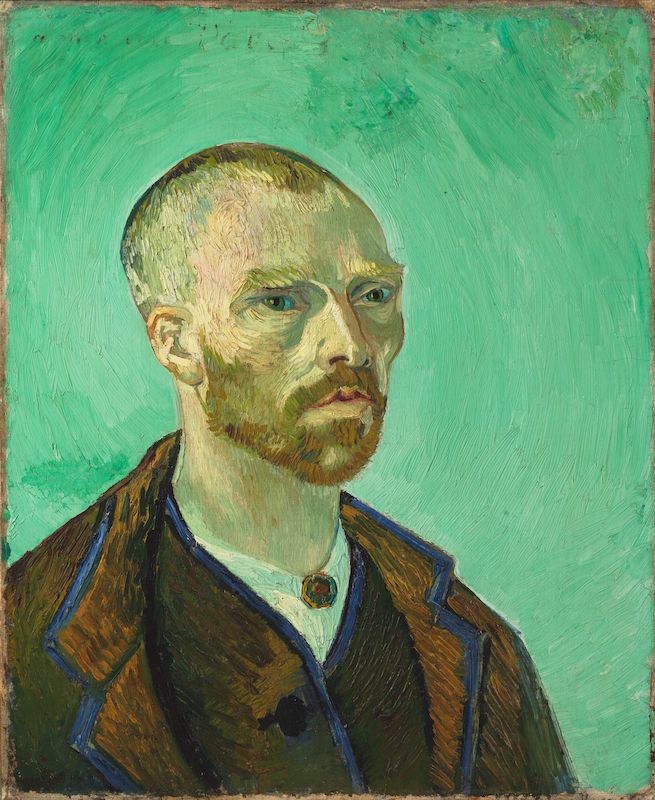

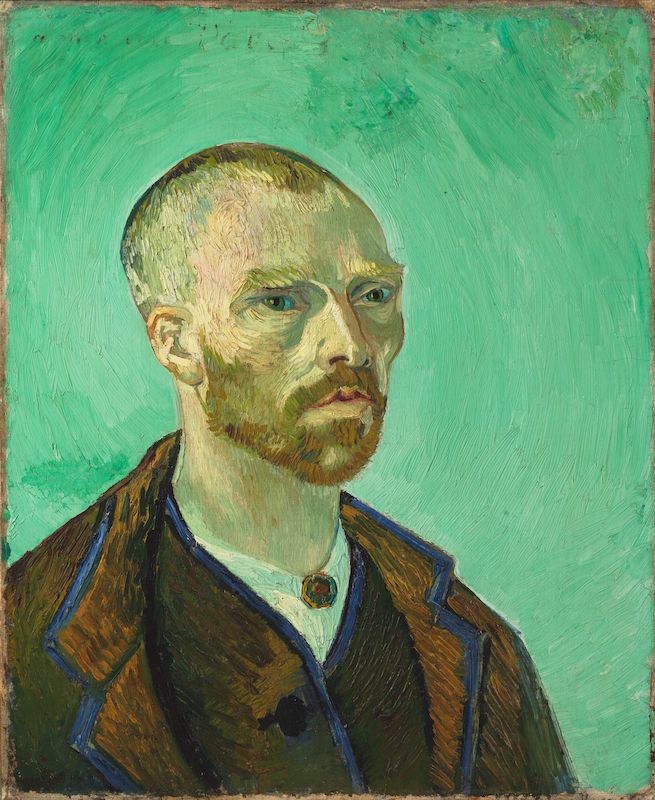

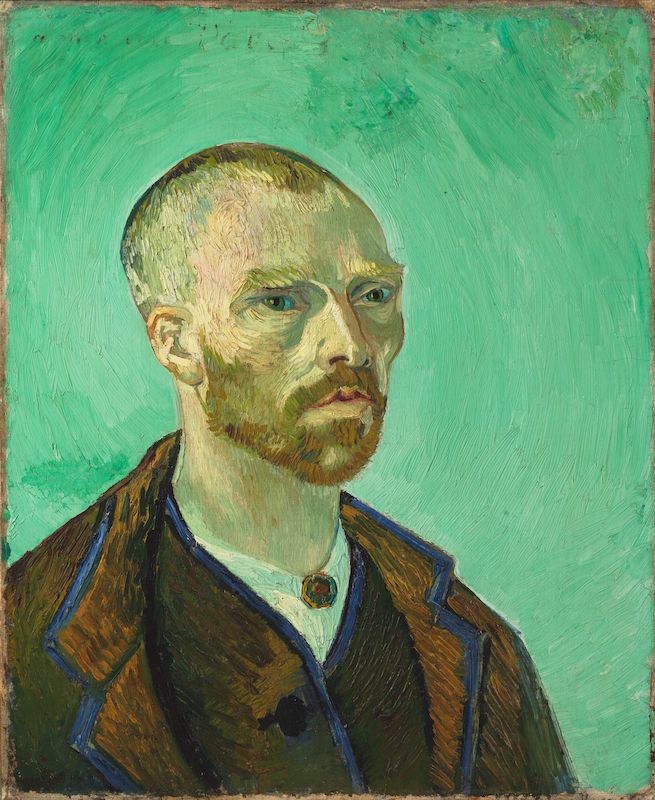

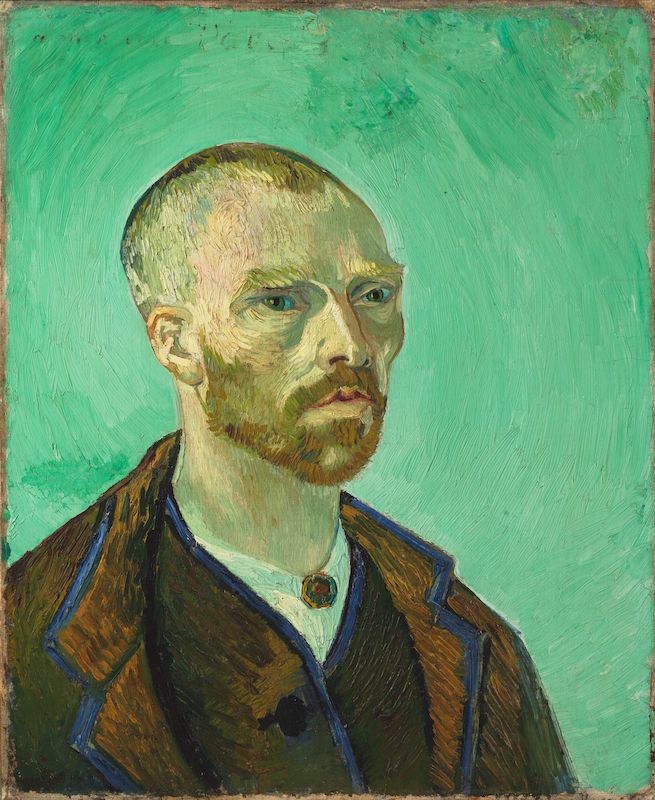

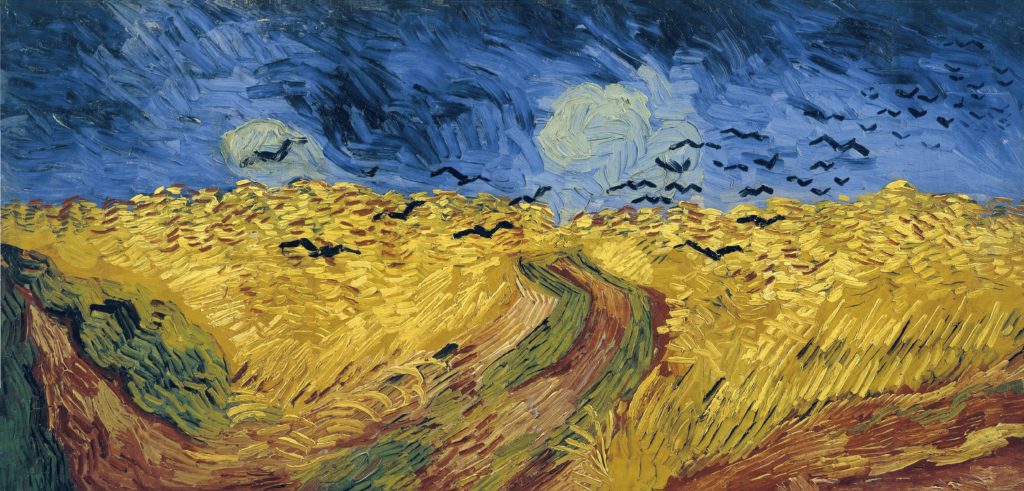

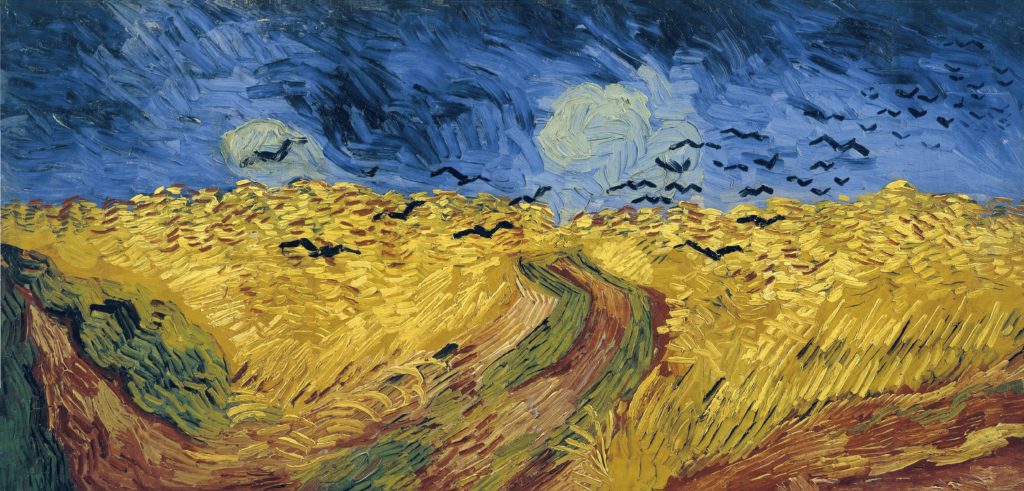

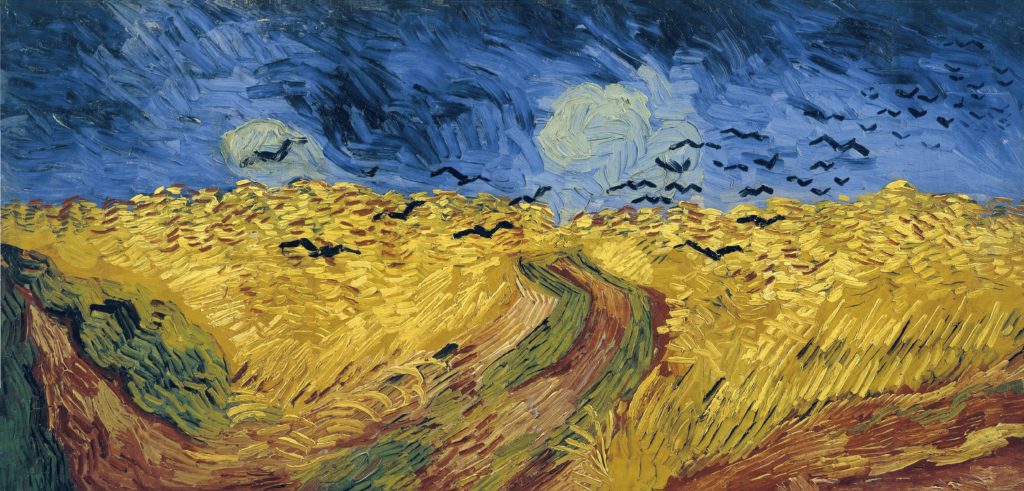

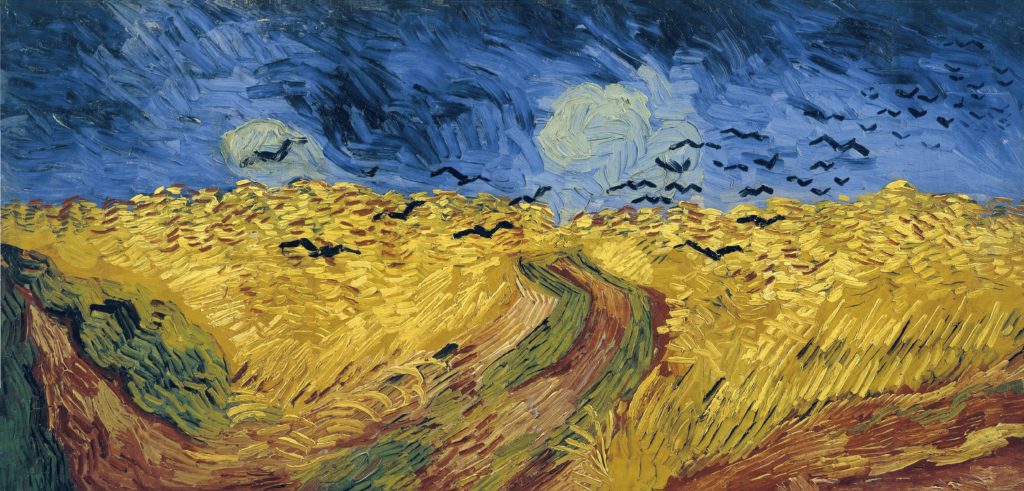

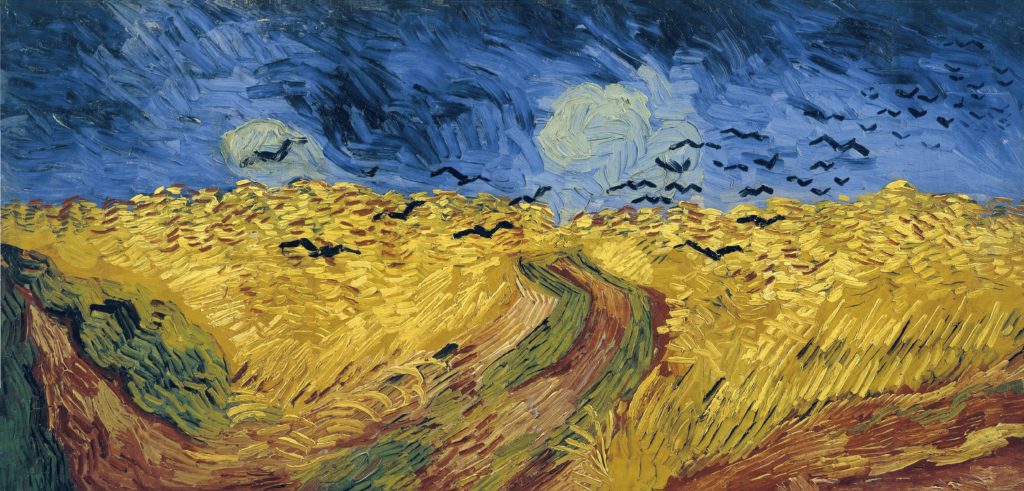

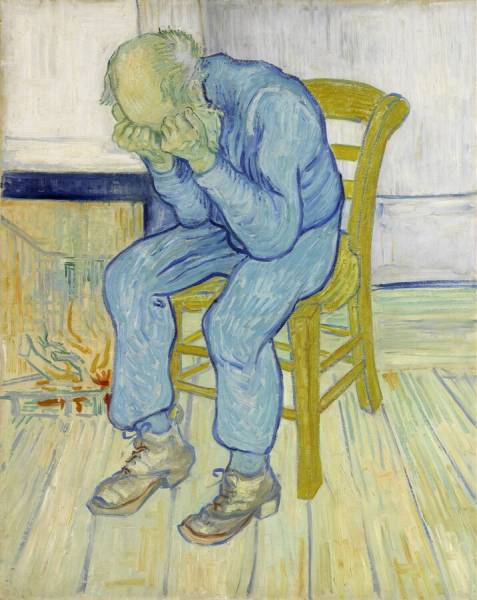

Post-Impressionist Vincent van Gogh is as famous for his mysterious death as for his iconic and expressive use of line and color. Did unbridled passion for art kill this troubled artist? Or did it perhaps save his life? Here is an alternative look at the mental health of Vincent van Gogh.

We can’t have a “diagnosis” for Vincent, but we can speculate that he suffered from a mental health disorder, and that he likely died by suicide aged just 37, although some speculate that he was shot by someone.

The story of his rages, his alcoholism, his self-harm are all part of the “tormented artist” narrative surrounding his life. People talk of his “battle” with mental illness, as if it was a wholly separate and ghoulish apparition. Some enjoy the romantic mythology of the “insane genius.” However, instead of the usual shock story of hacking off your own ear in despair, let us, like Alice in Wonderland, go through the looking glass and view this well-worn story from a different perspective.

Mental health problems are one of the main causes of the overall disease burden worldwide. One in four of us will be affected. None of us knows how or when a mental illness could become part of our daily life. There is still a significant amount of stigma around owning up to depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, eating disorders, or substance abuse. We can access supports and medications, however, that simply wasn’t available to Van Gogh back in 1890.

Throughout his life, Van Gogh produced over 2,000 artworks, over 800 of which were oil paintings. Most of his great work is said to come from the last few years of his life. Art was his one great love, the thing that always rewarded and excited him. In fact, he literally couldn’t survive without his beloved oils and canvases. Painting was his medicine with which he strove to stay sane. During a period in the hospital, when he had been denied his painting tools, his mental state, and behavior were seriously affected. In the end, the doctors realized that to survive, Van Gogh must have the chance to paint and create. He said:

I can very well do without God in my life and in my painting, but I cannot, suffering as I am, do without something that is greater than I am, which is my life, the power to create.

Vincent van Gogh, in letter to his brother Theo. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh.

Having people who understand and care for you is one of the greatest supports one can access during episodes of mental illness. Van Gogh had that support in his beloved brother Theo, and as recent investigations showed – also in his sister-in-law, Jo van Gogh-Bonger.

The correspondence the brothers shared through life illuminates much of what we know about the artist. Theo gave love, support, financial and practical help whenever his brother needed it. That is quite a burden for just one man though, and the Theo himself died soon after Vincent.

Vincent was born exactly one year to the day after his mother had given birth to a stillborn child, also called Vincent. Attachment theory today tells us that a parent who has had a traumatic loss may have difficulties with care and relationships, especially if there are unexplored issues around the idea of a “replacement” child.

We know that he had a strained relationship with his father and that they quarreled frequently. Vincent spent some of his early years away at boarding school, which may have fractured an already problematic family relationship. Blocked early attachments can leave scars that continue through to adulthood. We don’t know how much this impacted him, but today we would hope that a grieving parent, and a child born out of loss, would have more support from family and from their community.

Moving into adulthood and finding your place in the world can stretch and reward us, but it can also be disappointing.

Your profession is not what brings home your weekly paycheck, your profession is what you’re put here on earth to do, with such passion and such intensity that it becomes spiritual in calling.

Vincent van Gogh, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh.

Van Gogh spent his early career as an art dealer, spending some years living happily in London. However, he became disillusioned with buying and selling paintings and moved on to teaching. He worked at schools in Ramsgate and Isleworth, and seemed to have enjoyed the responsibility of caring for and educating his young charges. During this period he also found himself drawn to Bible study and he felt his life was being transformed – he felt he must become a Church Minister.

Studying theology at a university did not go well. Vincent described it as “the worst time of my life.” He persevered with his spiritual mission, and although he abandoned his studies, he threw himself into preaching duties in the harsh and impoverished coal mining region of Borinage, Belgium. His employers in the Church did not approve of Van Gogh’s immediate and passionate identification with the poverty-stricken miners. He recklessly gave away his clothes, his money, his possessions, and was finally dismissed from the Church. With his Evangelical career over, Vincent stayed and began to draw what he saw around him in the village of Cuesmes – he became an artist.

As already mentioned, his younger brother Theo and his wife, Jo, were a constant support to Vincent. They offered financial help for him to attend art school but the restrictions of the art education system stifled Vincent. He then moved to Paris to be closer to the Impressionists.

Always putting art before everything else, Vincent ate poorly while drinking and smoking too much. He spent much of his life in poverty, which has a proven link to depression. Although quoted as saying that “to do good work one must eat well and be well housed” he always prioritized art materials over food, clothes, or shelter.

He said in explanation:

The only time I feel alive is when I am painting.

Love and desire can make fools of us all, and Vincent was no exception. In 1881, in the early years of his art studies, he fell in love with his cousin Cornelia Adriana Vos-Stricker, known as Kee. Recently widowed and raising a young son, Kee did not welcome Vincent’s advances. In a particularly unpleasant episode, Vincent stormed to her parent’s home and demanded to see her. Kee’s father, protecting his daughter, said no, at which Vincent deliberately held his hand over on an oil lamp, saying he would burn his flesh until she gave in. The father simply turned off the lamp, and Vincent left in humiliation.

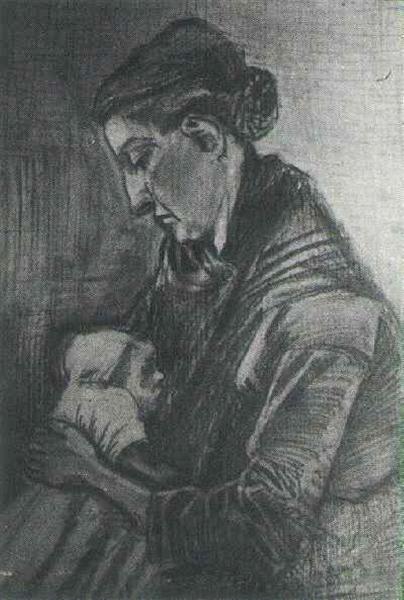

A year later, in 1882, Van Gogh moved in with Clasina Maria Hoornik, known as Sien. A pregnant prostitute, Sien was as volatile as Vincent, but his passion for her and his commitment to her children seemed genuine. Sadly this relationship, lived out in extreme poverty, lasted barely two years. Recovering from this trauma at his parent’s home, he met their neighbor Margot Begemann. She fell in love with Van Gogh but was herself in poor mental health. She attempted suicide by poison and although she recovered, the episode was devastating for Vincent. “I will not live without love” he said but romantic love eluded him his whole life.

We humans are a tribal lot, we need people who care for us, and who understand us. Although sometimes characterized as a solitary loner, Van Gogh dreamed of living in a commune of artists, inspiring and supporting each other.

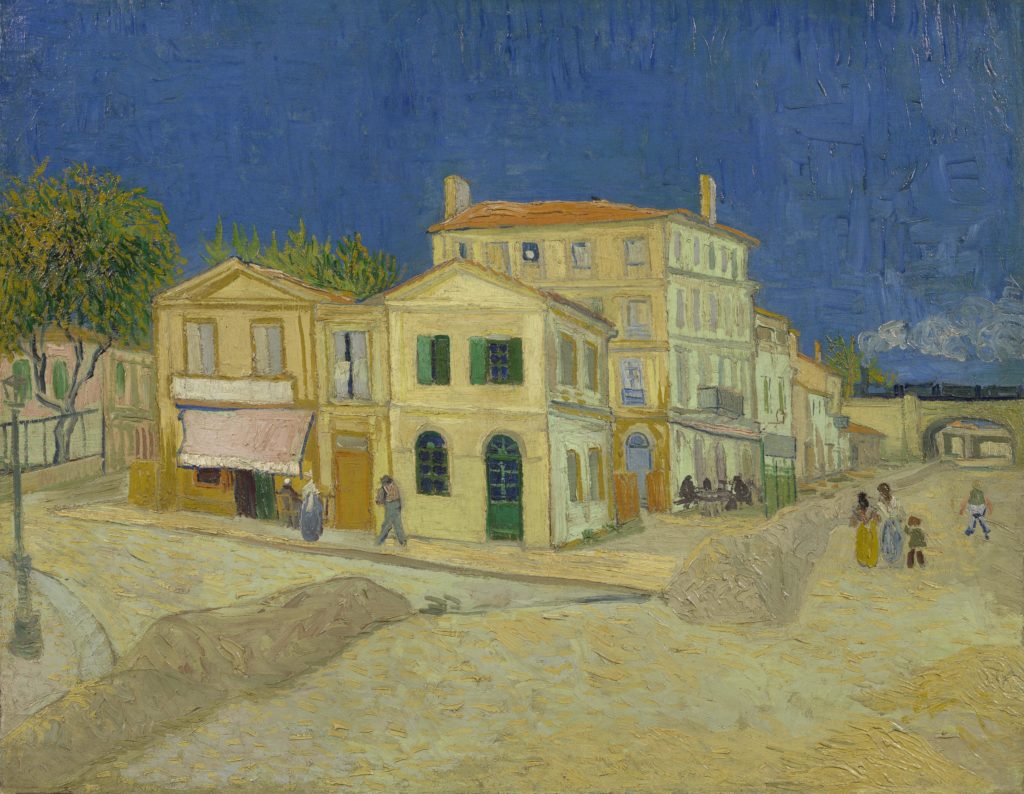

Paul Gauguin moved to Arles in 1889 to share a house with Vincent. Their initial warmth for each other and their shared passion for art descended into terrible arguments. At this point, Vincent severed his ear. At the same time, concerned by the erratic behavior of their artist neighbor, Arles residents sent a petition to the town mayor, demanding Vincent be expelled. This “not in my backyard,” small-town cruelty ended with the police removing a devastated artist from his home.

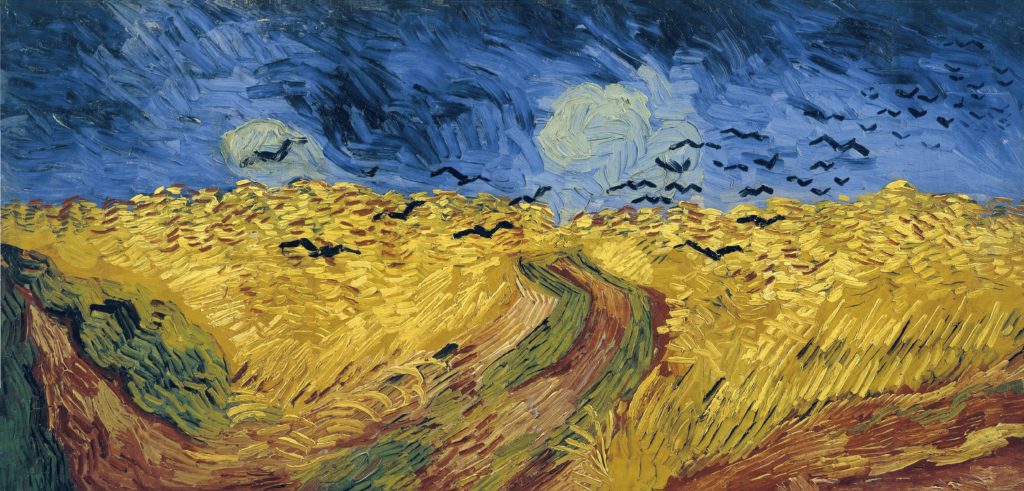

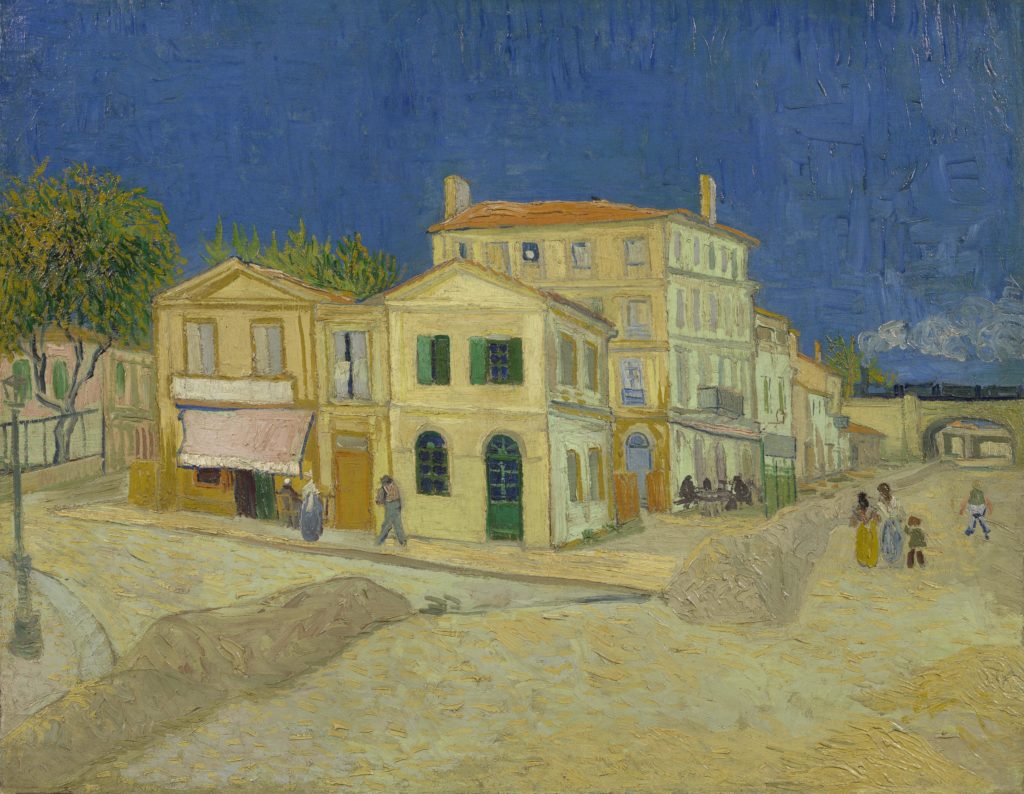

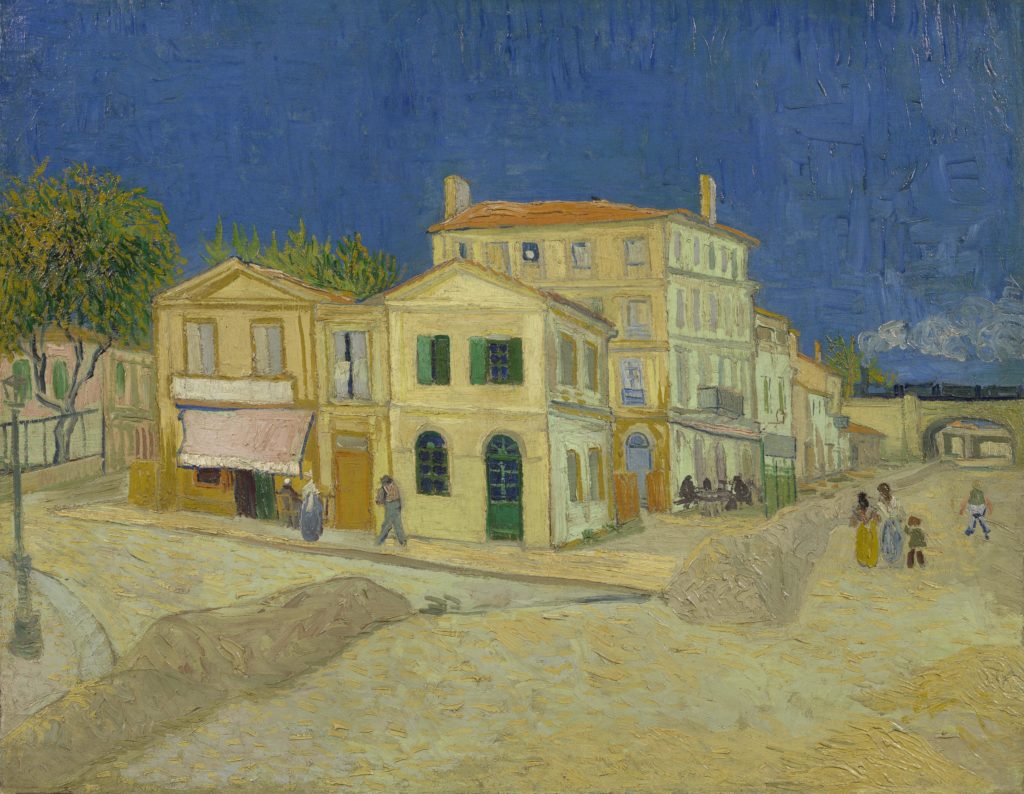

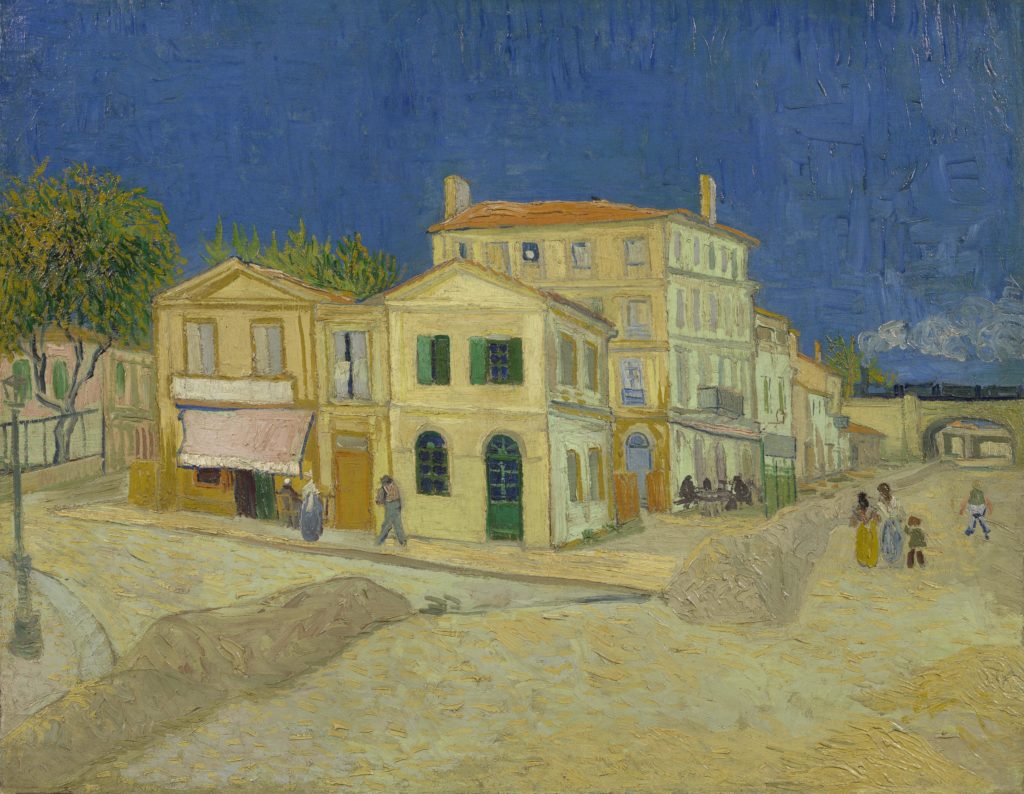

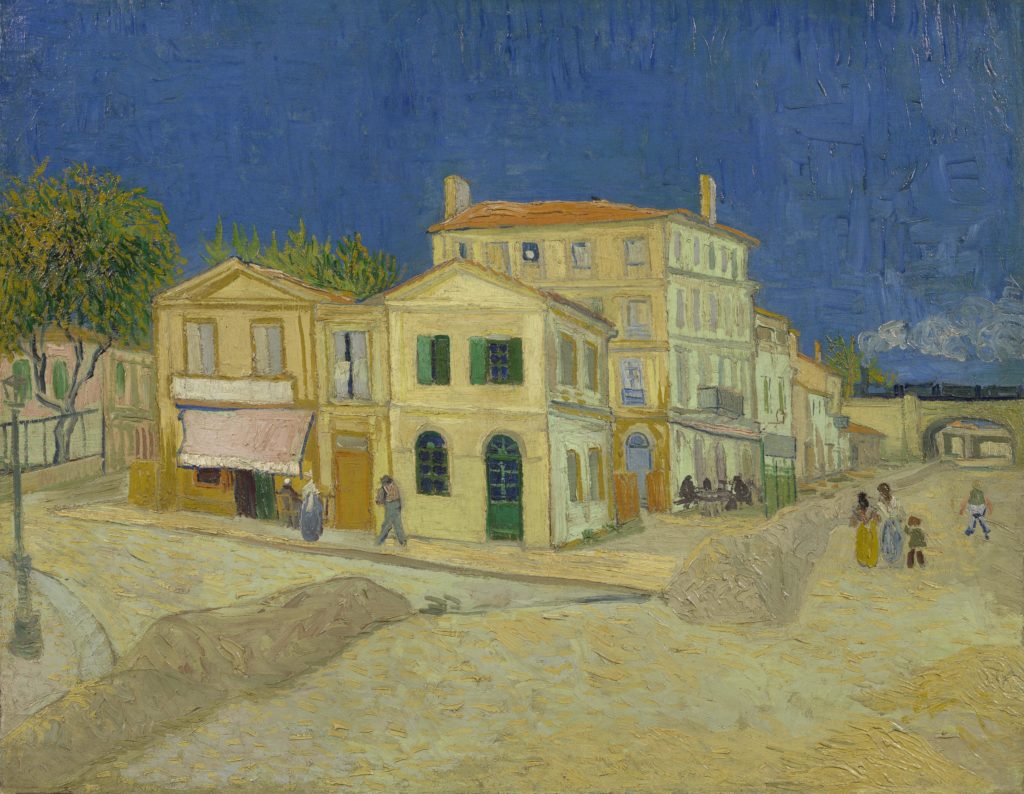

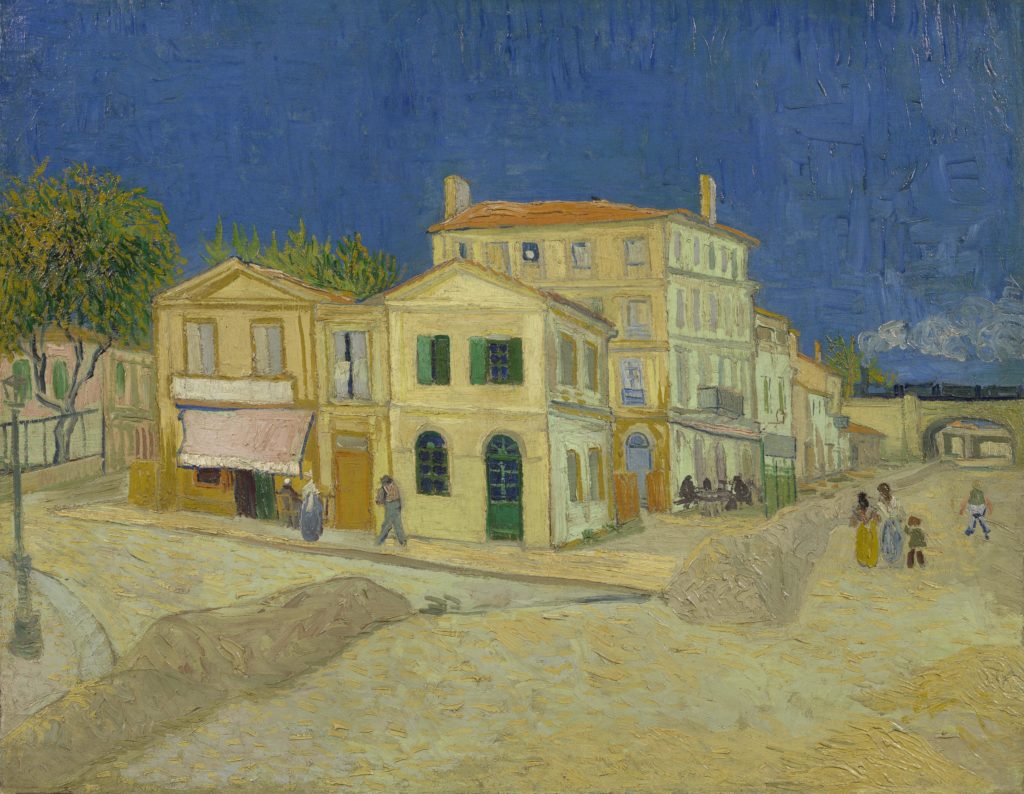

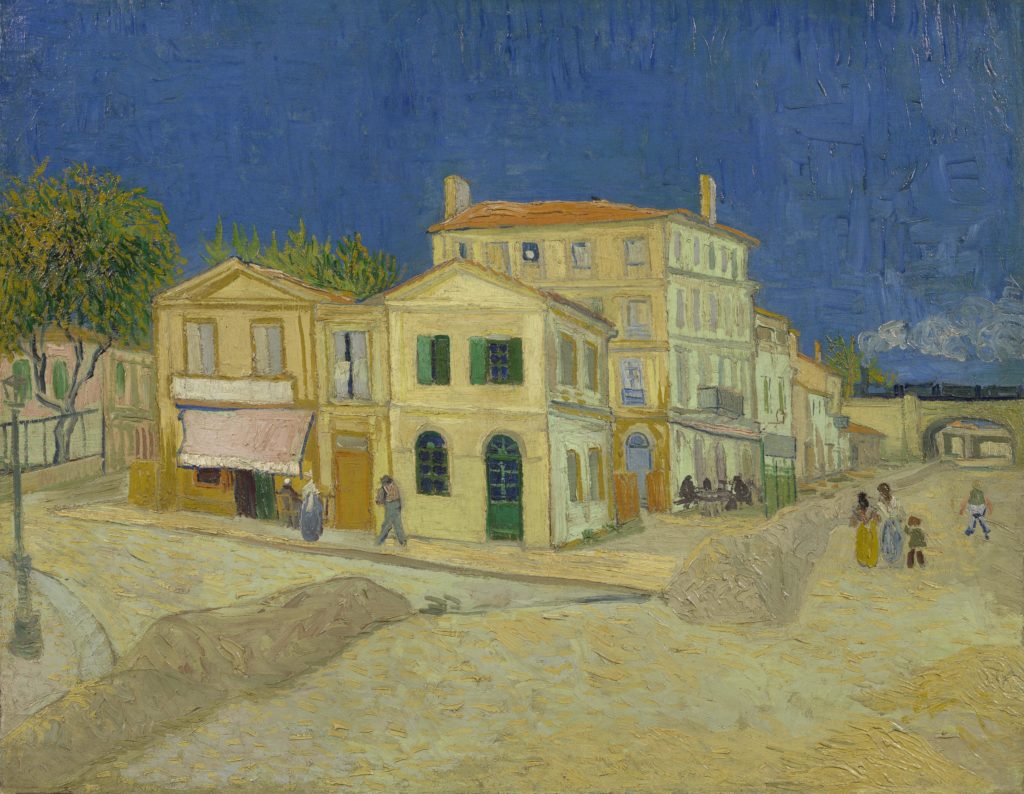

Although Van Gogh was drawn to cities like Paris, to gorge on art and wine, he could not last long in that frenetic milieu. He wanted nature – the sun, light, wind, and vistas of the countryside. In 1888, in Arles, he produced some of his best-loved works. He rented and spent many happy months in his famous Yellow House.

Today, we know that time in nature can be vital for mental health. Doctors might even prescribe forest bathing (or Shinrin Yoku as it is known in Japan) for depression and anxiety. Vincent yearned to be out in the fields, out in the landscape. Bad weather or too much city living affected him severely. He said:

If you truly love nature, you will find beauty everywhere.

Art lovers and historians speculate endlessly about what mental health conditions Vincent van Gogh might be diagnosed with today. Epilepsy, schizophrenia, porphyria, lead poisoning, manic depression, and alcoholism have all been suggested. We know he was prescribed bromide sedative and cinchona wine, made from quinine. It is also common knowledge that Van Gogh spent time confined to an asylum on more than one occasion. He was seriously disturbed by the noise of the other patients, the bad food, and the fact that no one had anything to do.

Most hospitals today have all kinds of therapeutic activities available to in-patients, but this was not the case back then. The rather bizarre treatment prescribed for Vincent was a series of hot and cold baths!

An interesting medical explanation for Vincent’s use of the color yellow was discussed by Paul Wolf in the Western Journal of Medicine. People receiving large and repeated doses of the drug digitalis often see the world with a yellow-green tint. They complain of seeing yellow spots surrounded by coronas, very much like those in Starry Night.

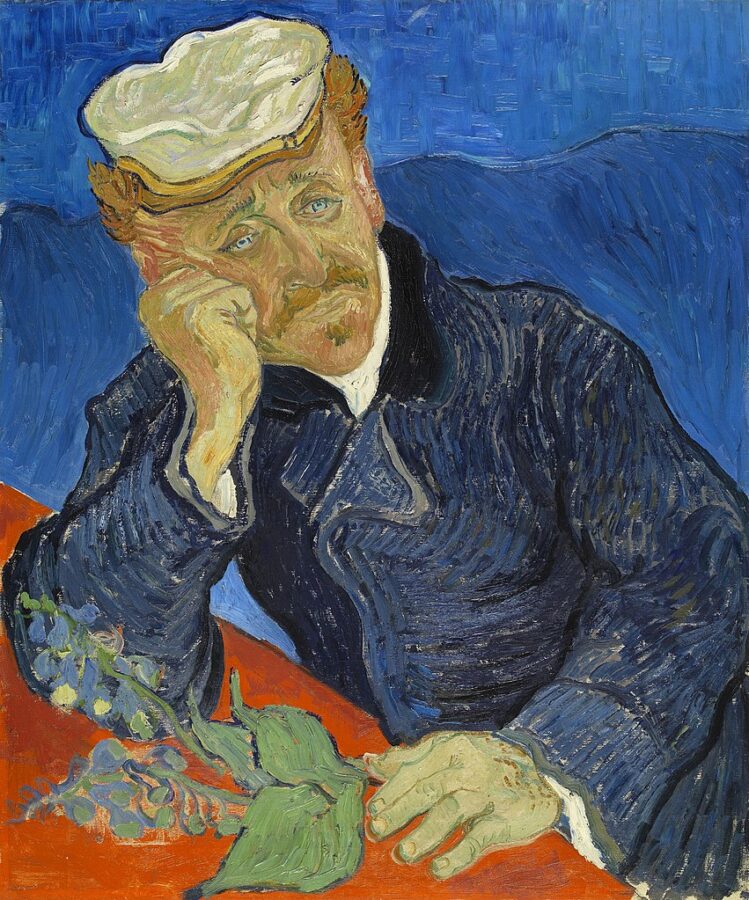

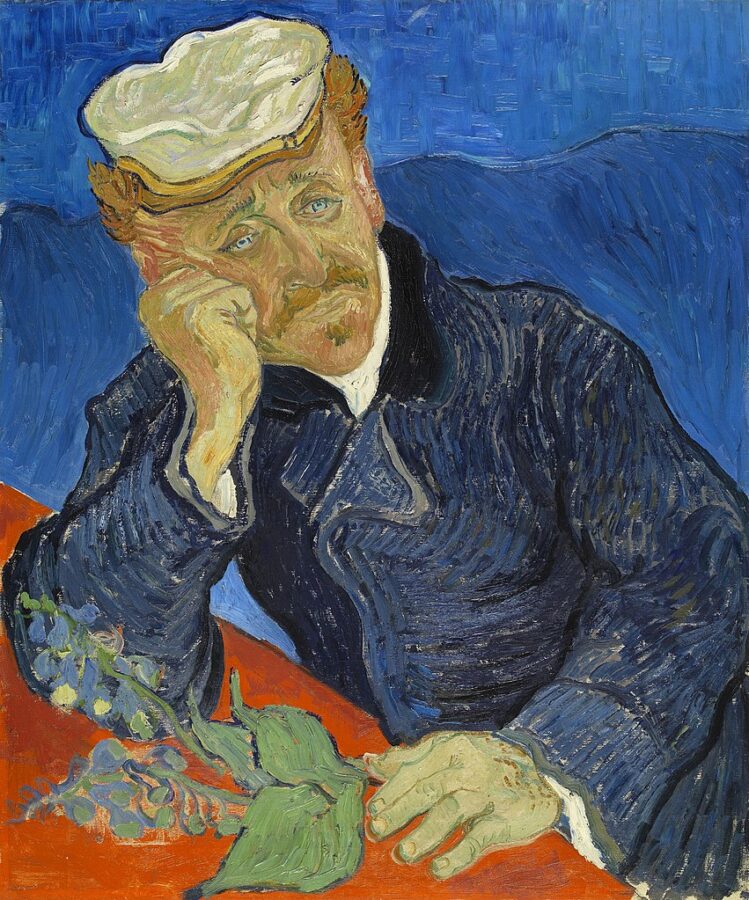

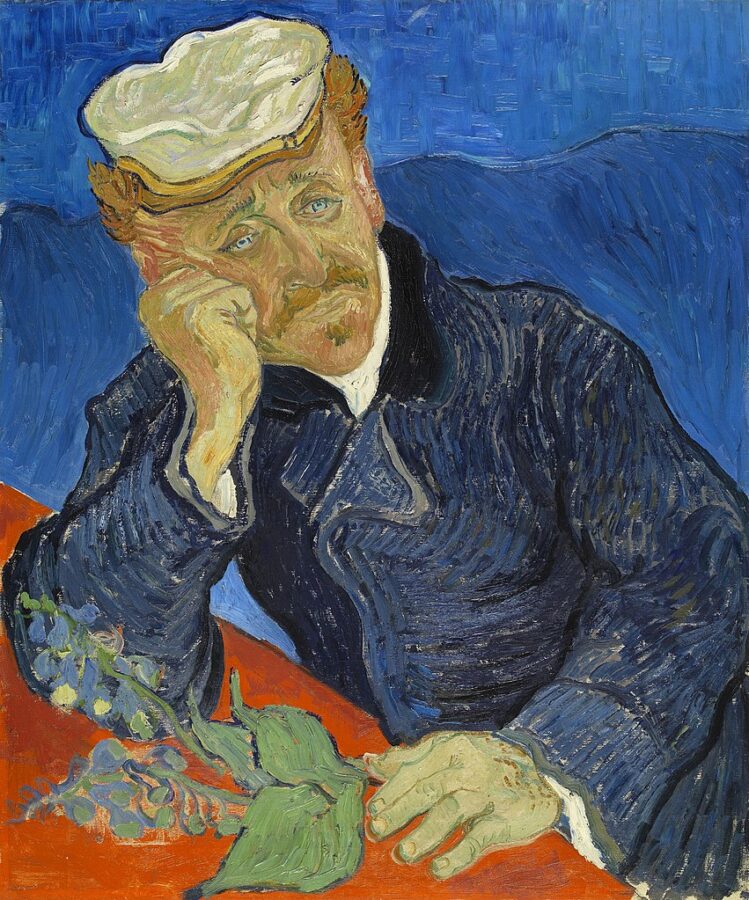

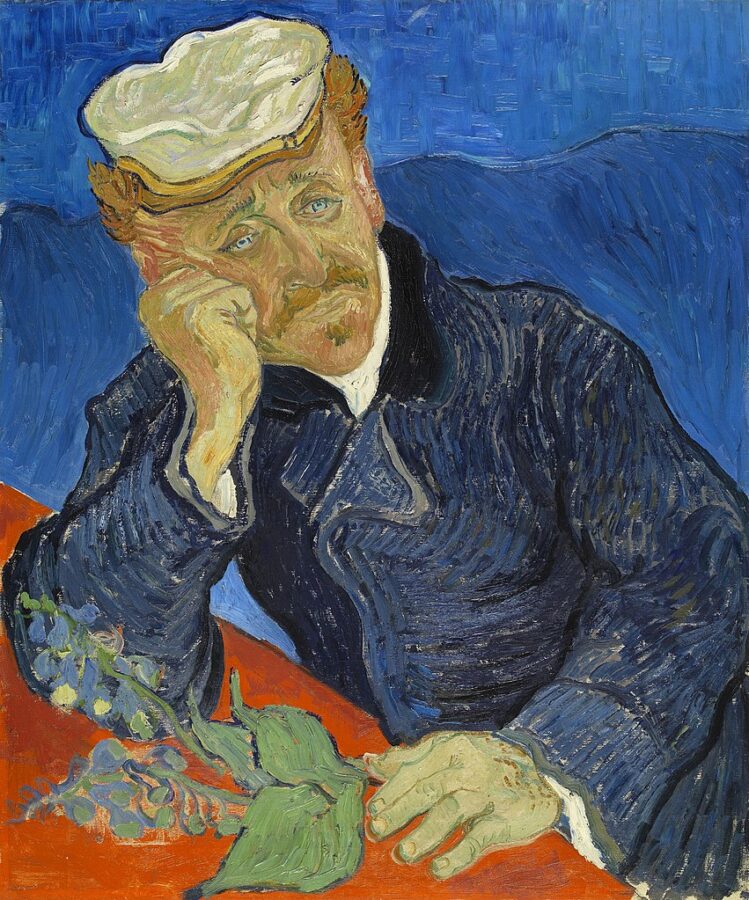

Homeopathic therapist Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, who treated Vincent in Auvers, may well have prescribed digitalis, a common treatment for epilepsy at that time. In fact, in one of Vincent’s portraits of Gachet, the physician holds a stem of Digitalis purpurea, the foxglove from which the drug is extracted (see below). Others have suggested that excessive intake of absinthe can cause the drinker to see the world through a yellow hue. However, the amount needed couldn’t possibly be ingested by anyone, not even the famed drinker Vincent!

Writing to his sister in 1889, Vincent wryly noted his own “medication” of choice, as advised by English writer Charles Dickens:

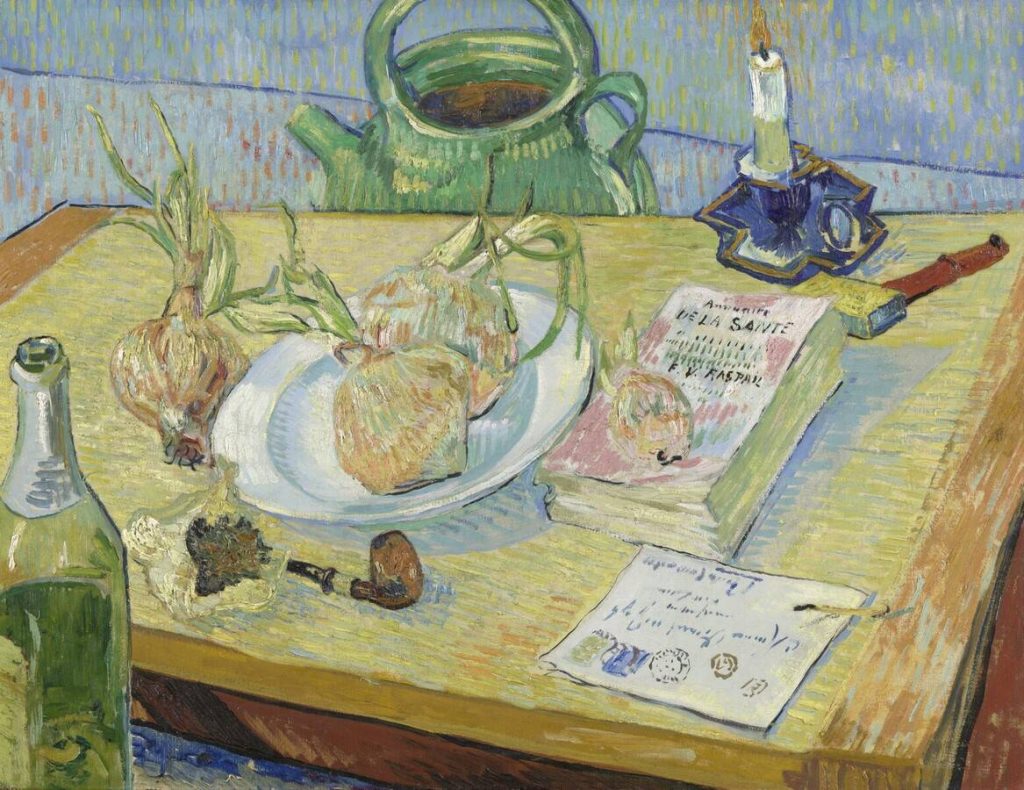

Every day I take the remedy that the incomparable Dickens prescribes against suicide. It consists of a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese and a pipe of tobacco.

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to Willemien van Gogh, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh.

Dr. Gachet seemed to care very much for his patient. His ability to correctly diagnose and treat Vincent was seriously in question though. The artist himself said of Gachet that he was “sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much”. Perhaps with the right care and the treatments we take for granted today, Van Gogh may have been able to go on to produce many more works.

If I could have worked without this accursed disease, what things I might have done (…).

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to Theo van Gogh, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh.

Sometimes, brotherly love, friendship, and help from well-meaning medics isn’t enough. Upon his release from another stay in the hospital in 1890, Vincent was exhausted, and his hopes for a full recovery had evaporated. “La tristesse durera toujours” he said (in English “the sadness will last forever”).

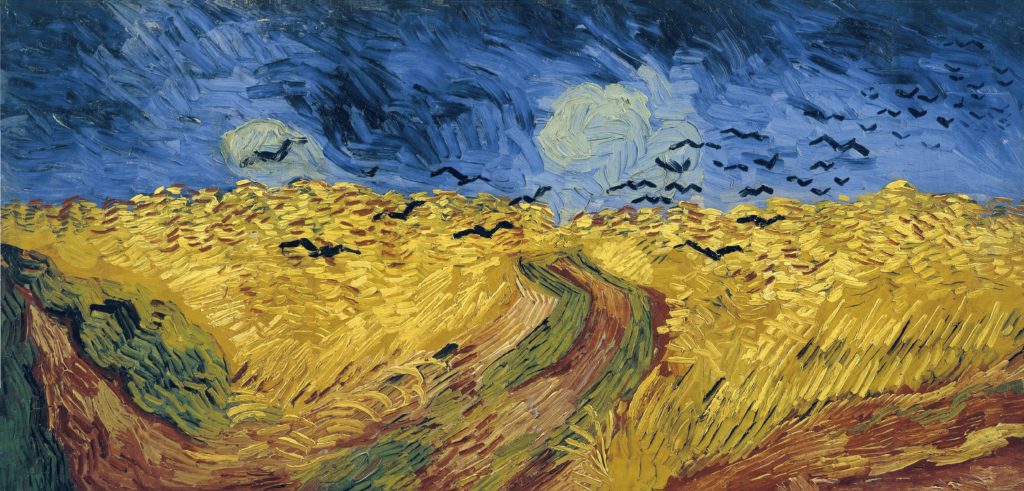

On July 27, 1890, while painting in the fields near his home, it is believed that he took out a revolver and shot himself in the chest. He died two days later, holding the hand of his beloved brother Theo. He has been mourned by the art world ever since.

The painter Emile Bernard, a long-time friend of Vincent, wrote poignantly about the funeral:

On the walls of the room where his body was laid out all his last canvases were hung making a sort of halo for him and the brilliance of the genius that radiated from them made this death even more painful for us artists who were there. The coffin was covered with a simple white cloth and surrounded with masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he loved so much, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was, you will remember, his favorite color, the symbol of the light that he dreamed of being in people’s hearts as well as in works of art.

Emile Bernard, in A Great Artist is Dead: Letters of Condolence on Vincent van Gogh’s Death, ed. Sjraar van Heugten and Fieke Pabst, Waanders, 1992.

We all have light in our hearts, but sometimes it is dimmed by circumstances of life and health. What we know now about mental health shows that Vincent van Gogh experienced a perfect storm of triggers: early childhood trauma, relationship tragedy, living in poverty, facing overwhelming adversity, being misunderstood or criticized by one’s peers, plus health conditions that could not have been properly diagnosed or medicated at that time.

Without his art, I suspect he would not have lived as long as he did, nor felt the passion and the love that he did. “Let us not mind being eccentric,” Vincent once said.

Normality is a paved road: it’s comfortable to walk, but no flowers grow on it.

Vincent van Gogh, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh.

Our wonderful, terrible, ordered, and disordered minds can take us to heaven and hell. Sometimes we’re sailing on calm seas, sometimes the storm rages. Vincent said:

The fishermen know that the sea is dangerous and the storm terrible, but they have never found these dangers sufficient reason for remaining ashore.

Vincent van Gogh, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh.

However, as we leave the shore we can ensure we take our life jackets – our loved ones, our books, our art, our music, and our medicine. Vincent believed that “the way to know life is to love many things” and that art consoles those broken by life. We can remember what makes life beautiful, we can ask for help, and above all, we can be kind, to ourselves and others.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!