Summary

Mermaids have been portrayed in various ways throughout art history:

- Seen as melancholic creatures living in solitude across many cultures, mermaids had long been connected (good or bad) with the sailors.

- The first known female mermaid-like creature was the Babylonian goddess Atargatis.

- Old sea maps use mermaids to suggest danger or bad weather; influenced by Christianity, mermaids were once seen as sexual predators.

- Mami Wata is a benevolent, healing mermaid integral to African culture.

- 19th-century people made mermaid-like objects to hoax spectators.

- Tale of Alexander the Great, as well as the famous Odyssey by Homer involve mermaids. Melusine from medieval folklore share similar physical traits. The epic narrative Ramayana introduces us to a mermaid princess named Suvannamaccha.

- Academic and Pre-Raphaelite arts paint mermaids as lustful creatures tempting men into sin and eventual death.

- Edvard Munch’s mermaid is a prime example of a post-Freudian symbol of the subconscious desire. Meanwhile, René Magritte depicted a Surrealist, reversed mermaid.

- Pop art, modern pop culture, and cinema produce an image of a “cute” mermaid.

- Some contemporary artists still stick with the traditional mermaid. Canute Caliste, a self-taught painter from Grenada is one of them.

- The mermaid is a symbol for the transgender and queer communities, as they echo the notion of “otherness.”

- Mermaids overall represent our relationship with the sea, fears, and longing for freedom.

Melancholy Mermaids

Often shown sitting alone, yearning for human company, but unable to live on the land. These wistful creatures are perhaps the most common in art history. Her beauty is tempting, but her mood is forlorn. The well-known image below was inspired by a poem by Alfred Tennyson from 1830:

John William Waterhouse, A Mermaid, 1900, Royal Academy, London, UK.

Who would be a mermaid fair, singing alone, combing her hair.

The Mermaid.

Sailor’s Mermaids

The Greeks feared the sirens of the sea, believing they lured sailors to their deaths with song. English seafarers believed a sighting was a bad omen, bringing death. Other cultures are a little more sympathetic – Chinese sailors believed they could offer immortality, and even cried pearls instead of tears. Mermaid spirit charms were used by Japanese fishermen. Ship figureheads often feature mermaid forms. These carved, wooden forms were meant to pacify the sea gods and gain the sailors safe passage across the ocean. In the image below, the relationship between this mermaid and sailor is unclear, but the embrace seems romantic. Is this an affectionate farewell? Did she just save him from drowning? Artist Howard Pyle died before he could finish the work, so we will never know for sure.

Howard Pyle, The Mermaid, 1910, Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA, USA.

Ancient Mermaids

Early civilizations were built around water – so it’s no surprise that the creatures of the sea would be loved and feared in equal measure. We think the first instance of a mer-creature appearing in mythology is a Babylonian god called Enki or Ea, 7,000 years ago. But that was a male. For our first mermaid, we go back to 1,000 BCE when the goddess Atargatis dived into a Syrian lake and transformed into a fish-like creature. Her figure can be found on ancient coins and carved into temples.

Atargatis statue, CE 100, Jordan Archaeological Museum, Amman, Jordan. Photo by Dennis Jarvis via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

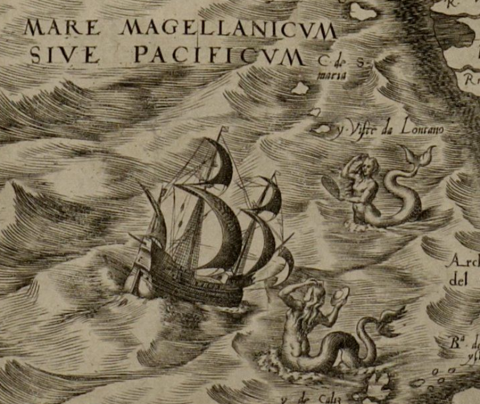

Mapmakers Mermaids

Early mapmakers would include sea monsters in their illustrations, indicating dangerous seas or areas of frequent bad weather. A very visual clue for possibly illiterate sailors. Early cartographers (map makers) were artists and explorers and there are many beautiful examples which include mermaids.

Diego Gutiérrez map, 1562, Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Religious Mermaids

The Church got in on the act of course. Their view was that mermaids were lustful creatures, vain sexual predators, and the worst of a woman. The French Bestiaire Divin, written by Guillaume, le Clerc de Normandie, in 1210 told of the mermaid’s sinfulness, calling them prostitutes and whores. Flowing hair, naked breasts, and refusing to answer to the rule of man – these maidens were strictly for the pagans. Although they then kept popping up in Churches everywhere.

Medieval carving, Cheriton Bishop Church, UK, 16th century. Escape to Britain.

African Mermaids

Mami Wata means Mother of the Waters and she is known across Africa. Myths vary, and in some, she can be gender fluid. The unifying characteristic of all these myths, however, is that Mami Wata is a benevolent creature, offering healing and wisdom, and warning of natural disasters.

Mami Wata figure, 1950s, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Hoax Mermaids

In 1822 showman PT Barnum exhibited his Feejee Mermaid (or Fiji Mermaid). It created immense interest but sadly was later found to be a very clever con. Visitors hoping for a fishy beauty instead found a dried-up corpse composed of half a fish sewn onto half a monkey. Similar fake mermaids can be found in museums across the world.

The Buxton Mermaid, 18th century, Buxton Museum and Art Gallery, Buxton, UK.

Greek Mermaids

A famous Greek tale involves the sister of Alexander the Great. Thessalonike was transformed into a mermaid upon her death in 295 BC, and she lived in the Aegean Sea. Only if her brother was said to be alive and ruling the world, would she allow safe passage to ships. Perhaps the most well-known tale is written by Homer, where the sirens of The Odyssey try to lure heroic Ulysses to a watery death.

Herbert James Draper, Ulysses and the Sirens, 1909, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston upon Hull, UK.

Medieval Mermaids

The Melusine appears in medieval tales – sometimes she has a serpent-like body, sometimes she has wings. Born to a human father and fairy mother, her story does not end well. As in most medieval tales, women must fall and fail in order to be educated. Mermaids unexpectedly appear in copies of the Bible too – in the image below they frolic beneath Noah’s Ark.

Anton Kobergers, German Bible, Noah’s Ark Woodcut, 1483, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

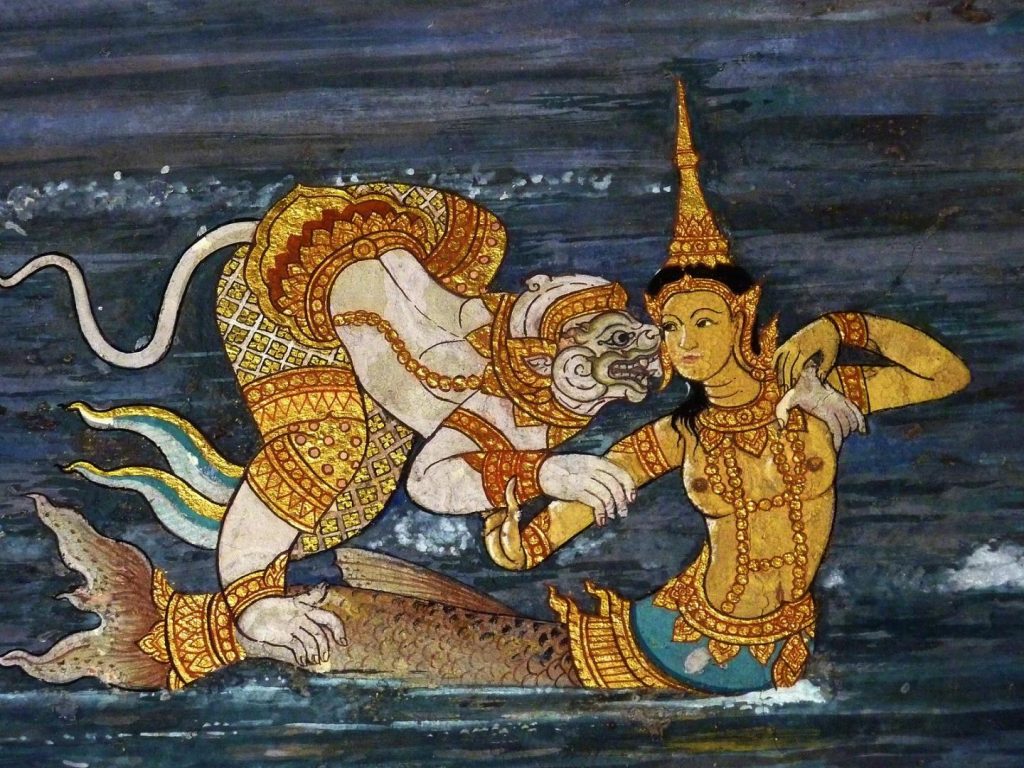

Southeast Asian Mermaids

Suvannamaccha (the golden fish) is depicted in murals and paintings and appears in the epic poem The Ramayana. Suvannamaccha meets one of the heroes of the tale, Hanuman, who is trying to build a bridge of stones across the sea. She tries to stop him, but falls in love with him, and ends up helping him in his task.

Ramakien Murals, 1783, Bangkok, Thailand. Photo by Photo Dharma via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

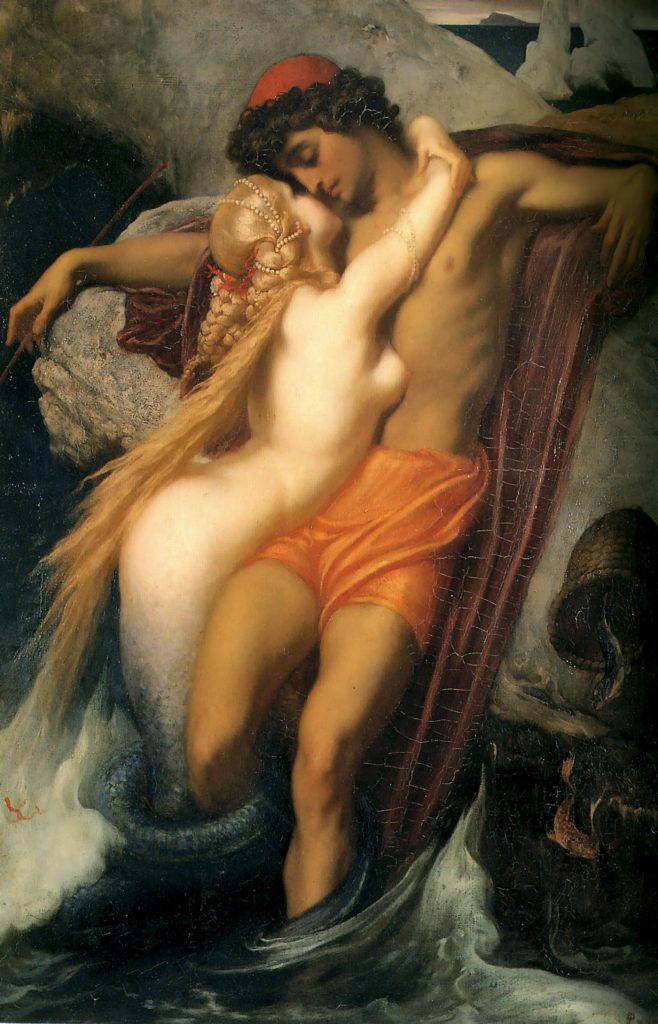

Temptress Mermaids

The work shown below was inspired by a poem by Goethe, which tells the story of a mermaid who rises from the waters to complain to a fisherman that he is enticing her children (the fish) to death in his nets. The mermaid’s beauty lures the fisherman into the water and to oblivion. Notice the crucifix shape of the fisherman’s body, and the mermaid tail coiled around his legs. The mermaid, with her seductive, destructive power, lures the handsome, secular Christ down to his death.

Frederic Leighton, The Fisherman and the Syren, 1856, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, Bristol, UK.

Pre-Raphaelite Mermaids

Victorian painter John William Waterhouse is a favorite of the British public. His romantic, nubile female nudes are a perfect example of the male gaze. There was an uproar when Manchester Art Gallery removed Hylas and the Nymphs from the display as part of a project with artist Sonia Boyce, looking at issues of race, gender, and sexuality. The gallery states that the (temporary) removal was part of a discussion around the presentation of women in art history, particularly the sexual objectification of the female body. The almost exclusively male press and art historians did not approve.

John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896, Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK.

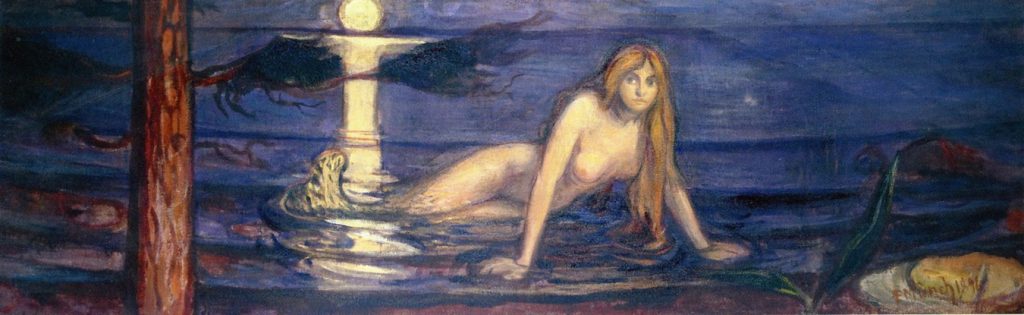

Post-Freudian Mermaids

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, had firm ideas about our hidden urges, and the mermaid seems the personification of the desires of the subconscious. Freud spoke of men’s castration fears, and the mermaid perfectly illustrates the rapacious, flesh-eating woman. This contrasts painfully with men’s desire to return to the safety of the watery womb. Edvard Munch painted more than one mermaid. In the image below she is mid-transformation, and we get a real sense of desire mixed with anxiety.

Edvard Munch, The Mermaid, 1896, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

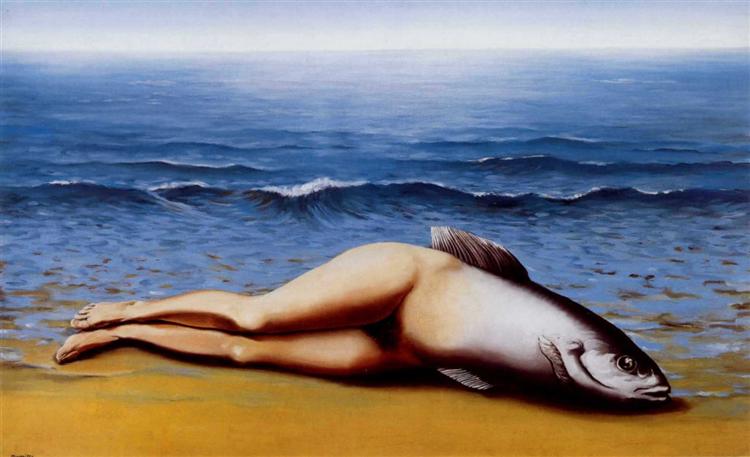

Surrealist Mermaids

René Magritte shows us a mermaid abandoning her oceanic environment, but in a surreal twist, she is a reversed mermaid, with a fish-like head and human legs. Magritte at his subversive best, although there is a sadness to the image – the mermaid is seemingly stranded and can live in neither air nor water.

René Magritte, Collective Invention, 1934, private collection. WikiArt.

Literary Mermaids

It is no surprise that mermaids appear in literature as well as visual art. The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Anderson in 1836 is perhaps the most famous. Arthur Rackham, esteemed English illustrator, produced some gorgeous images that are still very collectible. In contemporary fiction, two recent novels have explored deep cultural issues around power, sex, and the place of women in society. The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey and The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gower are both highly recommended.

Arthur Rackham, Rhinegold and the Valkyries, 1910. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

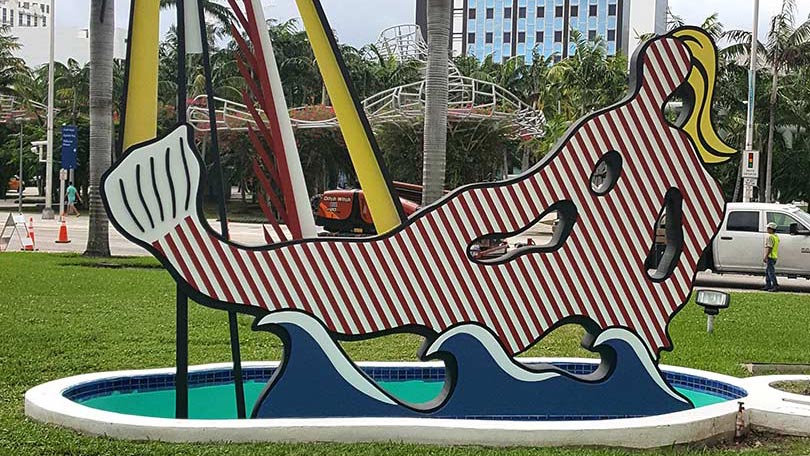

Pop Culture Mermaids

As science and reason asked us to give up our mythical creatures, still we clung to the mermaid. In the 1970s, Pop Art fanboy Roy Lichtenstein added a very modern mermaid to the waterfront in Miami. Tom Hanks fell for blonde beauty Darryl Hannah in the blockbuster fantasy film Splash in 1984 and Disney Studios produced the nubile red-head Ariel in 1989. In 2023 Disney plan to re-visit the story with a black mermaid. Racists across America have been trolling Disney ever since.

Roy Lichtenstein, Mermaid, 1979, City of Miami Beach, Department of Art in Public Places, Miami, FL, USA.

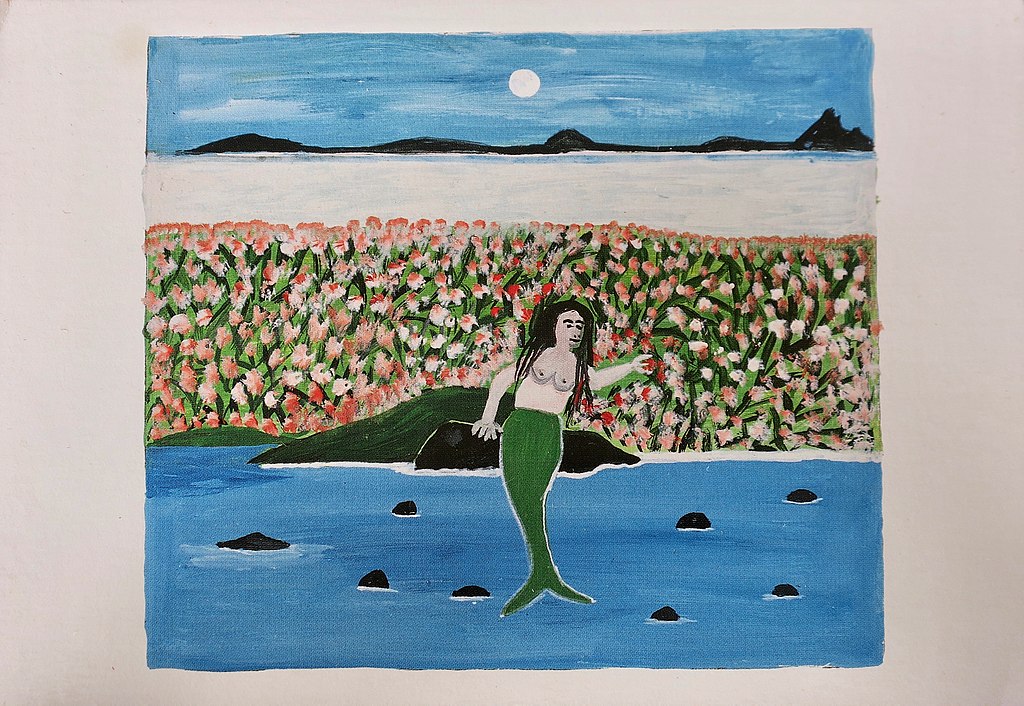

Contemporary Mermaids

As the mermaid became “cuter” in modern society, they dropped out of favor in fine art. But we have to include the work of Canute Caliste, a naïve painter from a tiny Caribbean island near Grenada. He saw a vision of a mermaid when he was just nine years old, and they haunted his work until his death in 2005.

Canute Caliste, Mermaid. Photo by NickCT via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

In a very different artistic style, Connie Imboden photographs the human body in water, using the natural play of light on the body underwater producing fascinating images.

Queer Mermaids

Queer culture, and especially the transgender community, has embraced the symbol of the mermaid, and her transformative “otherness”. The dichotomy of their half-fish, half-human appearance speaks to the LGBTQI+ community (lesbian, gay, bi, trans, questioning, intersex, plus others). The mermaid breaks the heteronormative rules of conventional society and celebrates gender as a fluid concept. Mermaids UK, the transgender youth network worked with sculptor Eve Shepherd and the Royal Museum Greenwich to produce Person of the Sea.

Eve Shepherd, Sea People, 2019, National Maritime Museum, London, UK.

By Any Other Name

Across the globe, mermaid-like sea creatures have a myriad of names and incarnations. Almost all involve an aquatic creature with a human-like head and upper body, but with the tail of a fish: Naiads or Nereids; Sea Nymphs; Lamia; Rusalkas; Aycayia; Iara; Ningyo; Nixes; Merrows; Selkies; Kuliti.

Symbols

Vital symbol of female freedom and fertility or the chaos of the ocean and the vengeful cruelty of free women? Mermaids are all this and more. Some say mermaids are alien extra-terrestrials, some say they are the ghosts of drowned women, and some say they lure humans to water and feast on their flesh. Some say they are simply manatees or dugongs, seen through lonely, sleep-starved eyes. If they are of human origin, did mermaids escape to the freedom of the sea or were they banished there?

Arnold Böcklin, In The Sea, 1883, Art Institute Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Our Obsession

Beautiful and seductive, yet wild and violent, the mermaid is the perfect representation of our human relationship with the sea. It offers adventure and freedom, but it is unpredictable and unfathomable. Our early ancestors crawled up out of the sea, our own lives begin in a watery womb, and it seems our fascination with these wonderful water creatures will never be sated.

Gustav Klimt, Mermaids, 1899, Albertina, Vienna, Austria. Gustav Klimt.

Frans Francken, Allegory the Ship of State, 16th century, National Maritime Museum, London, UK.