Madness in Art: A Powerful Connection

Madness and art have long shared a profound and powerful connection, where the boundaries between genius and instability often blur. Many acclaimed...

Maya M. Tola 28 October 2024

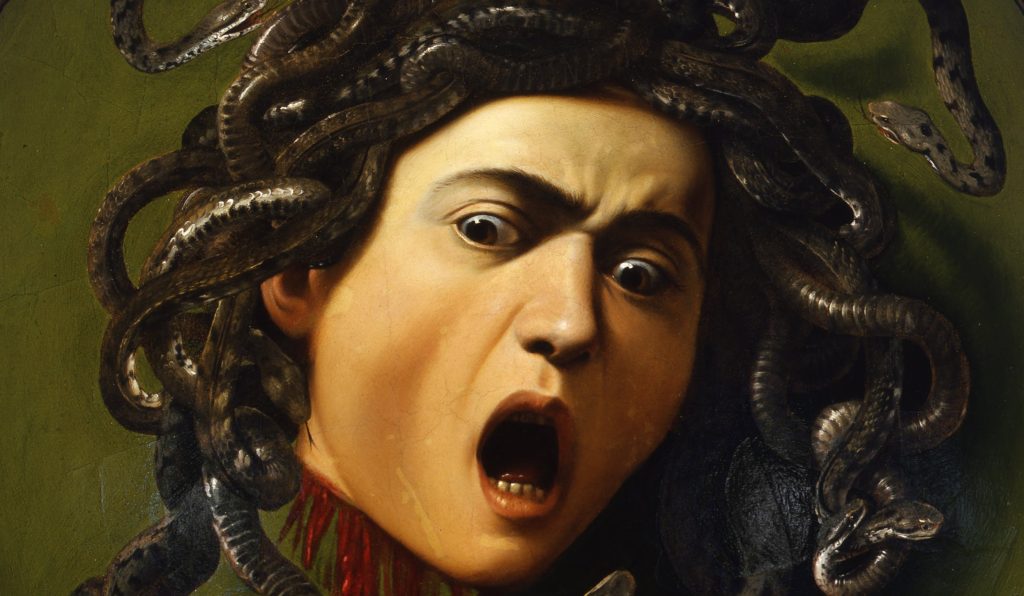

The Medusa story – terrifying or tragic? Some months ago, a controversial new statue of Medusa was unveiled in New York, so let’s take this opportunity to have another look at this most fearsome of women.

Whether you are an ancient academic reading Homer, or a teenager watching a fantasy TV series, you will have come across a version of this tale of a snake-haired monster who turns men to stone. Medusa is a name we all recognise, but do we know her?

Until April 2021 a seven foot bronze nude will stand outside the Criminal Courthouse in Manhattan, New York, USA. The work was actually created in 2008, a decade before the #metoo campaign, but in 2020 Argentinian artist Luciano Garbati petitioned the New York Arts in the Park program to mount his statue Medusa with the head of Perseus as a symbol of triumph for victims of sexual assault. The millionaire sexual predator Harvey Weinstein was convicted in the Court right across from where Medusa currently stands, armed with a mighty sword, her gaze sober and intense.

Luciano Garbati says he was inspired by a 16th-century bronze by Benvenuto Cellini Perseus With the Head of Medusa. Garbati wanted to flip the story on its head and look at it from Medusa’s viewpoint. Our writer James Wray takes a closer look at the story of Cellini and Perseus here.

I have always been utterly repelled by the much celebrated Cellini statue. Although a spectacular piece of technical sculpting skill, it seems to me the very personification of centuries of male violence and the glory associated with it. Perseus stands on the dying body of Medusa, triumphantly holding her head aloft. Her neck and severed head gush with blood and gore. But we are looking at the blood and gore of a woman’s body, not a monster, despite the serpent-like hair. This is the normalisation of gendered violence, writ large in a public space.

There are many versions of the Medusa story. The earliest tales tell of three Gorgon sisters, who were fierce and terrible haters of mortal men. But there is no mention of snakes. Others tell of hybrid part-human / part-animal creatures with beards, tusks, scales or fearsome teeth.

Some scholars of ancient languages suspect that the original ‘Gorgon’ might have been a chamber of gold, not a monstrous woman, making Perseus nothing more than a commercial ‘gold-digger’ who journeys to find a cache of coins which carry a gorgon head upon them.

Others suggest the Medusa myth is a contaminated version of the ancient Minoan, Hindu or Serpent goddess tales. In these we see the female figure who brings life and death. Both terrible and wonderful, these stories celebrate the cycle of creation, and are certainly not about dangerous women who need crushing.

Move on to Ovid, and we see Medusa as a beautiful celibate woman, with golden hair, who is raped by Neptune (also called Poseidon in Greek versions of the myth). She is punished by the jealous goddess Minerva (also called Athena), who inflicts on her a writhing head of serpents for hair, whose gaze turns men to stone. Medusa hides herself away in shame, but Minerva/Athena sends Perseus after her, with a magical shield. He deflects Medusa’s deadly gaze with his shield, cuts off her head and carries it as a trophy to terrorise his enemies. Ovid’s audience seemingly had no problem accepting wrath against a rape victim as both right and just. But in cultures where women were treated as commodities and where rape was permissible by law, that should sadly come as no surprise.

Later, the Classical Greeks and the Romans seem to have embroidered the fable with much more detail. We see winged human females with snakes for hair. We see the beginnings of the seductress image, the femme fatale, who provokes man (or god) to commit rape. This ‘seduction’ is explained as a divine right, which is to be celebrated, mythologised and eulogised. The list of stories which buy into the ‘rape as exciting plot twist’ category is very long, but top of the list of rapists is the rapacious Hades who forces himself on every beautiful woman or goddess he sees: he abducts Persephone, he rapes Callisto, Leda and Alcmene. The god Poseidon turns himself into a stallion in order to rape grieving Demeter (mother of the lost Persephone). Oh, and Hades also raped Demeter, who was his sister. Entertaining? I don’t think so.

Academic and TV presenter Professor Mary Beard states that the roots of misogyny can be traced to antiquity (Women and Power, A Manifesto, Profile Books, 2017). A dangerous conflation of femininity, erotic desire and violence seems to conclude that a woman can incite a man to rape her. At which point he is cleared of all ethical and moral responsibility. Woman as commodity. Woman as object. We allow men to present the creative, vital energy of woman as something to be feared and suppressed. In so many cultures strong, loud women are cast as a threat, their authority demonised.

Sigmund Freud wrote Das Medusenhaupt (Medusa’s head) in 1940. His conclusion was that Medusa represents the male anxiety of castration. There is a rumour that Benveneto Cellini, the sculptor we discussed above, despised the ‘feminisation’ of Italian politics, and his Perseus with the head of Medusa was his vicious response to the threat of women taking power. Certainly looks that way to me!

But it’s not just the sculptors and painters who fear for their manhood. TV and film-makers, writers and politicians have all used the Medusa myth as a focus for their fear and hatred. The films Clash of the Titans (1981 and re-made in 2010) and Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010), all portray Medusa as a prize bitch who must be destroyed.

Compare this with episode 15 of the US TV fantasy series Charmed which re-boots the Medusa myth, focusing on the idea of her as survivor rather than a villain. This is a mainstream teen TV show, so all credit to them for exploring the issues of body autonomy and sexual assault in such a forthright and sympathetic way. At the end, a female character saves the day by looking deeply into Medusa’s eyes and acknowledging the crimes committed against her. Here Medusa curses those who look the other way when justice is needed.

Donald Trump compared his rival for the 2016 US presidency to Medusa. Posters, tote bags and mugs showed the severed head of Hillary Clinton, held aloft by a triumphant Trump. Also thrown through the Medusa-mill were the suffragettes, fighting for the vote. And individuals as diverse as Madonna, Marie Antoinette, Oprah Winfrey and Angela Merkel. Muting female authority was, and still is, the gleeful aim.

Feminists have fought to reclaim Medusa, as a symbol of female rage, or as a shamed victim requiring justice. For them, Perseus is neither heroic nor blameless. Feminist theorist Hélène Cixous famously said about Medusa:

“She’s not deadly. She’s beautiful and she’s laughing.”

Hélène Cixous; Keith Cohen; Paula Cohen, The Laugh of The Medusa, Signs vol.1, no.4, 1976.

I see Medusa as a reminder to us all to cast a harsh and judgemental gaze on the societies we inhabit. Toxic masculinity and dysfunctional ideas around sexual consent are both still glorified in art and culture. We must stop blaming, slut-shaming and silencing the victims of male violence. Look into the piercing eyes of Medusa. If her gaze is fierce and terrible, or even deadly, do not look away. Because maybe, just maybe, you deserve to shrivel under her critical judgement?

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!