5 Facts about the Counter-Reformation in Art You Need to Know

The Counter-Reformation was the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation spreading through Europe during the Renaissance.

Anna Ingram 5 December 2024

10 February 2025 min Read

No, I am not indulging in casual profanity, in this painting, we are actually looking at God’s bare bottom and it graces the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, courtesy of Michelangelo. When I gaze at this world-famous chapel, certain questions spring to mind: Does God prefer pink? And, if he is all-powerful, why does he have to be supported by putti (cherubs)?

It is unclear why the gluteus maximus has such fatty coverings in humans, as we are the only ape that has them. It seems the size and shape of those buttock muscles maybe have to do with us being bipedal and mobilizing on two legs. Everyone loves a bubble-butt! But although his David sculpture (below) was a man, Michelangelo’s Deity does not walk, he hovers, swishes, and swoops like Superman.

In the story played out on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Michelangelo’s God creates the sun, moon, and vegetation. Is it strange to create solar systems alongside peas and carrots? Anyway, he then shoots off giving us a clear shot of his receding and naked backside. God mooning! Shock horror!

I won’t be so distasteful or irreverent as to delve into the other function of the rectum but surely the Almighty would be above such earthly processes. We can only conclude we are in the realms of man (Michelangelo) making God in his own image, rather than the biblical tale of God making man in his own image.

Today we view the Sistine Chapel through eyes educated by the Enlightenment, with a good dose of Empiricism from the scientific age. We must accept that the work is a product of Michelangelo’s age in its style and manner. This was work undertaken at the height of the Renaissance when anatomy, depth of field, and perspective were thoroughly mastered and artists could present us with perfect figurative images.

I personally question the style and aesthetic of the Sistine Chapel, but I know I am in a minority. Across the globe, we see an attitude of complete and utter blind adoration. It would seem this uncritical partiality all started with Giorgio Vasari, a pupil of Michelangelo and his first biographer (see Lives of the Great Artists).

This uncritical view of the Sistine Chapel was certainly still alive and well in the 18th century. This is Goethe’s comment:

Until you have seen the Sistine Chapel, you can have no adequate conception of what man is capable of accomplishing. At long last the alpha and omega of all things known to us – the human figure – has come to grips with me and I with it.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey, 1787.

And this continued through to the 20th century to today, where august art historians like Kenneth Clark and Andrew Graham Dixon are still singing from the same hymn sheet of perfection.

My problem here is about style and aesthetic. Is perfect figurativeness what we want for this subject matter? Consider what Michelangelo was portraying: the creation of the heavens and the earth; Adam and Eve; the Deluge; the Day of Judgement and Prophets and Sibyls foretelling the future. These are all metaphysical, supernatural fantasies. Do we want all these characters to appear as a bunch of gym trained 21st century body builders on steroids?

I question whether God, the supreme and ultimate creator, is a bloke who looks like a macho old stevedore. That kind of male paternalistic template might have served the ends of the Catholic Church in the past, but would believers today think their God anything like Michelangelo’s depiction? Though there can never be any serious comparison, I would prefer a lighter touch, as we might have seen if the work was done by Leonardo da Vinci, or even Vittore Carpaccio.

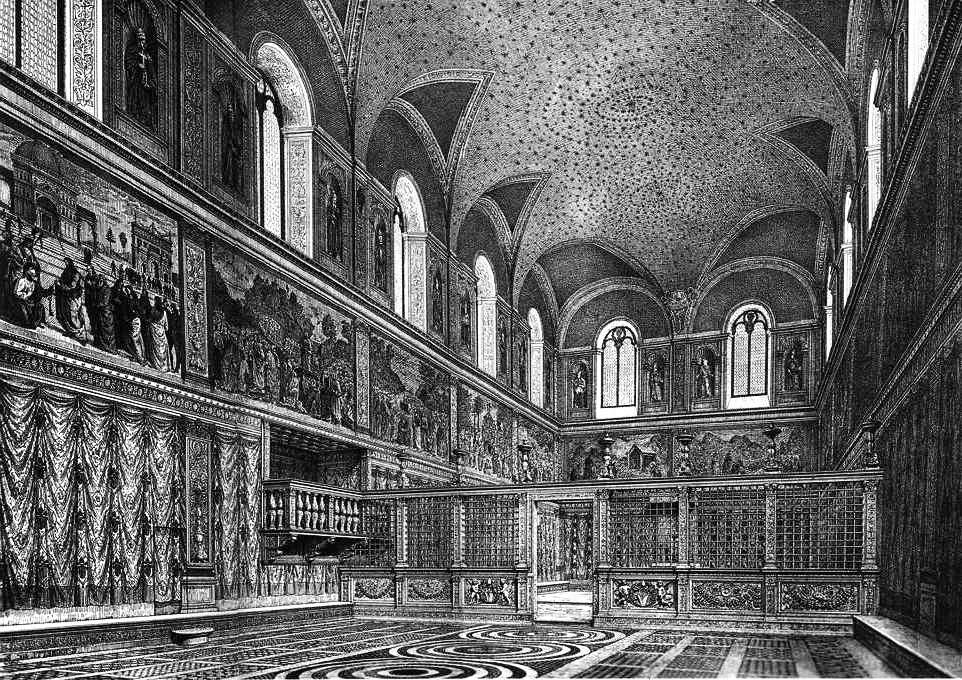

But it is not just the inside of the Sistine Chapel that disappoints. The chapel architecturally is rather dull. It looks Romanesque, but lacks the mathematical harmony found in so many buildings of that style. This is because it is not Romanesque at all, as it was constructed circa 1470, where the style of the age was late decorated gothic. Gothic it ain’t, nor decorated either, so outside it could certainly stand embellishment.

Michelangelo might have been the last to decorate the Sistine Chapel but he was certainly not the first. Sandro Botticelli, Cosimo Rosselli, and Pietro Perugino were all there before him. The Sistine Chapel is, in a way, a whole gallery and museum crammed into one small space, but where little can be appreciated.

It is reminiscent of the visual chaos that was the norm in the Royal Academy, and similar art institutions, right up until the early 19th century. For me, the decoration added by Michelangelo presents us with such a tumult of images and color that adds up to visual overkill.

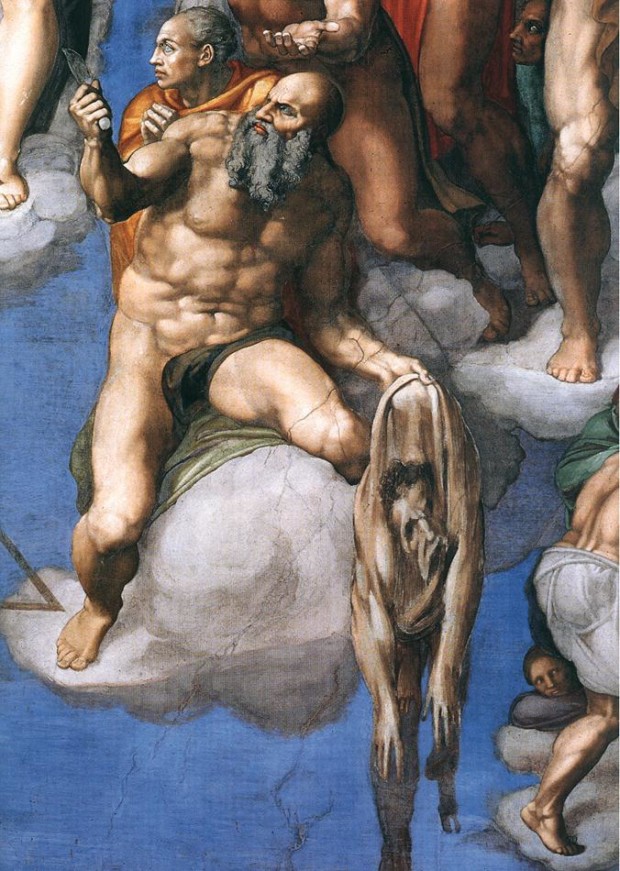

The Last Judgement which covers the altar wall is undoubtedly magnificent. And the devil is literally in the detail. The barque of the damned, is spectacular. Next to it is the supposed self-portrait of Michelangelo himself as flayed skin, shown below.

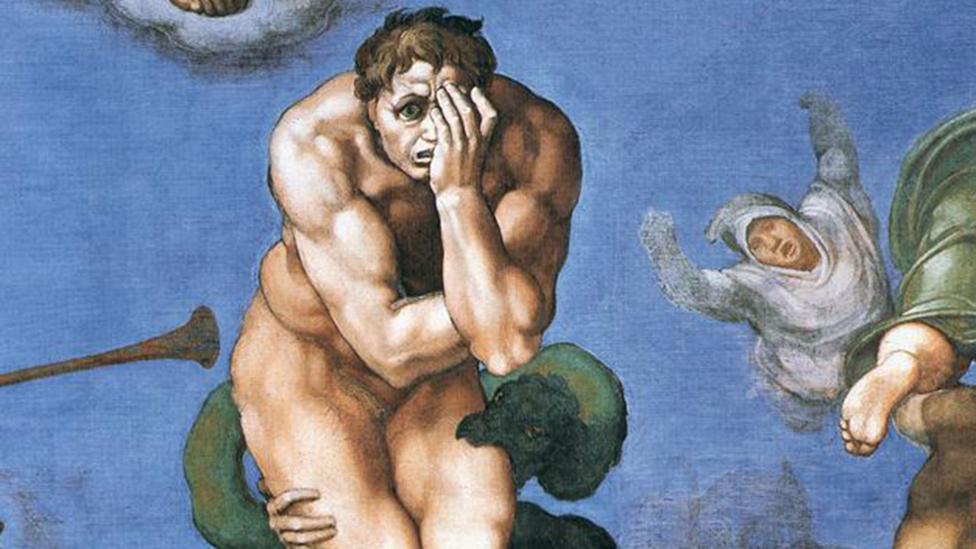

His image of “the despair of the damned” has such universal resonance that its influence can surely be traced right through to Rodin and beyond.

Yet consider Adam and Eve and surely we have the detail bedeviled by the excess of the whole? They are completely overwhelmed by the framing decoration and are towered over by classical nudes that have no narrative or ecclesiastical relevance at all.

There are some truly wonderful visual narratives throughout, but they are completely lost because they are basically crammed into the pendentive (the curved triangle where a dome intersects with its supporting arches).

Look at the story of The Punishment of Hamen. Told episodically, as was the fashion, Michelangelo is highly creative in his use of the space.

The shape of the pendentive begs the crucified form to be seen flat-on as it would fit perfectly. Instead, Michelangelo shows us the crucifixion from the left-hand side-on and uses a wall with a door to connect chapters of the story. If this was a free-standing painting, scholars would extol its virtues as a masterpiece. Instead, it is stuck in a corner of the ceiling and barely appreciated.

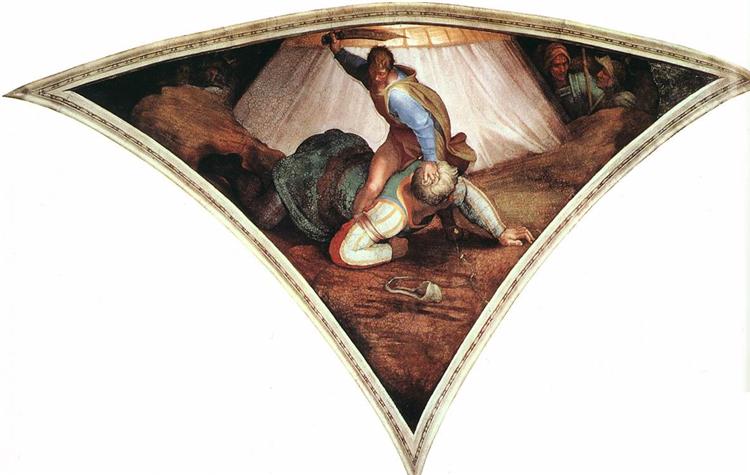

The painted story of David and Goliath is so different from Michelangelo’s definitive sculpture just few years before, but who knows of it? He might as well have painted on the interior of a broom cupboard.

Michelangelo was, of course, predominantly a sculptor. That is obvious when viewing his frescos. Look at his depiction of Daniel: the contrapposto, the assemblage, the active limbs. Michelangelo is almost experimenting in 3D and these are clearly the work of a sculptor.

In fact, if it were not for the Sistine Chapel, we would never think of Michelangelo as a painter at all. He painted a few other works in the whole of his long life: The Conversion of Saul and The Crucifixion of St Peter are both frescos. The Doni Tondo is a free-standing panel painting. The Entombment is incomplete. There are two other works possibly attributed to Michelangelo – The Torment of St. Anthony and also The Madonna and Child with St John and Angels (usually known as The Manchester Madonna). This brings the total to a mere six paintings.

Who do we blame for this over-gilded lily of a chapel, and this blind adoration of such aesthetic chaos? Michelangelo never wanted to be a painter, he wanted to sculpt, and he certainly didn’t want to paint the Sistine Chapel. He was dragooned into it by a bad-tempered old Pope, Julius II (aka as the Warrior Pope who humbly took his title from Julius Caesar).

Not the most spiritual of Popes, he spent most of his pontificate going to war. It is said he fathered a daughter and apparently had several male lovers. Michelangelo was not a fan and initially refused the Sistine commission. During the execution of the work he complained bitterly about late payment.

This brings us back to God’s bottom. Is this rather startling depiction Michelangelo’s resentment for having to paint rather than sculpt? Michelangelo was bullied by Pope Julius II for the slowness of his work. Was Julius being a pain in the butt? Do you see where I am going here?

Julius II was not a popular man. Neither Erasmus nor Martin Luther thought very much of his holiness. He could be viewed as the Harvey Weinstein of the Renaissance. So was Michelangelo covertly disrespecting his holiness, trusting that in the visual chaos of the ceiling the insult would pass unnoticed? That we will never know, but it makes for a fascinating piece of Renaissance gossip!

Ian Munday Since his retirement to Wales he has been studying art history and creative writing. He gives guided garden tours at Powis Castle in Welshpool and also assists at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in Machynlleth.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!