5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

In the vibrant tapestry of art history, few relationships resonate as profoundly as that of Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso. These two titans of 20th-century art forged a friendship that endured over fifty years, leaving an indelible mark on the world of modern art.

Miró and Picasso first crossed paths in the effervescent artistic scene of 1920s Paris. On March 1st, Miró arrived with a package from Picasso’s mother, whom he had previously visited in Barcelona to see her son’s pictures there. By then Picasso, already an influential figure, cast a significant artistic shadow that reached the budding Miró on those early encounters.

In the beginning Picasso – naturally reserved with me – lately now, after having seen my work, very effusive; hours of conversation in his studio, very frequently…

MINK Janis, Joan Miró: 1893-1983, Taschen, 2000

The seasoned maestro and the aspiring apprentice found common ground within the avant-garde movements of the time. On one hand, Picasso’s innovative spirit and audacious creativity left an imprint on Miró’s early works. On the other, Miró admired Picasso’s ability to challenge artistic norms, setting the stage for a dynamic artistic dialogue.

Joan Miró, Horse, Pipe and Red Flower, 1920, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, USA.

It was during that very same summer that Miró painted in Mont-Roig, Catalonia, a composition with direct homage to Picasso: Horse, Pipe and Red Flower. In fact, this still life in a collage-styled composition depicts the Parisian influences from the Cubist and Surrealist movements. In the center, we can appreciate the representation of the publication Le Coq et Arlequin by Jean Cocteau precisely opened on a drawing made by Picasso.

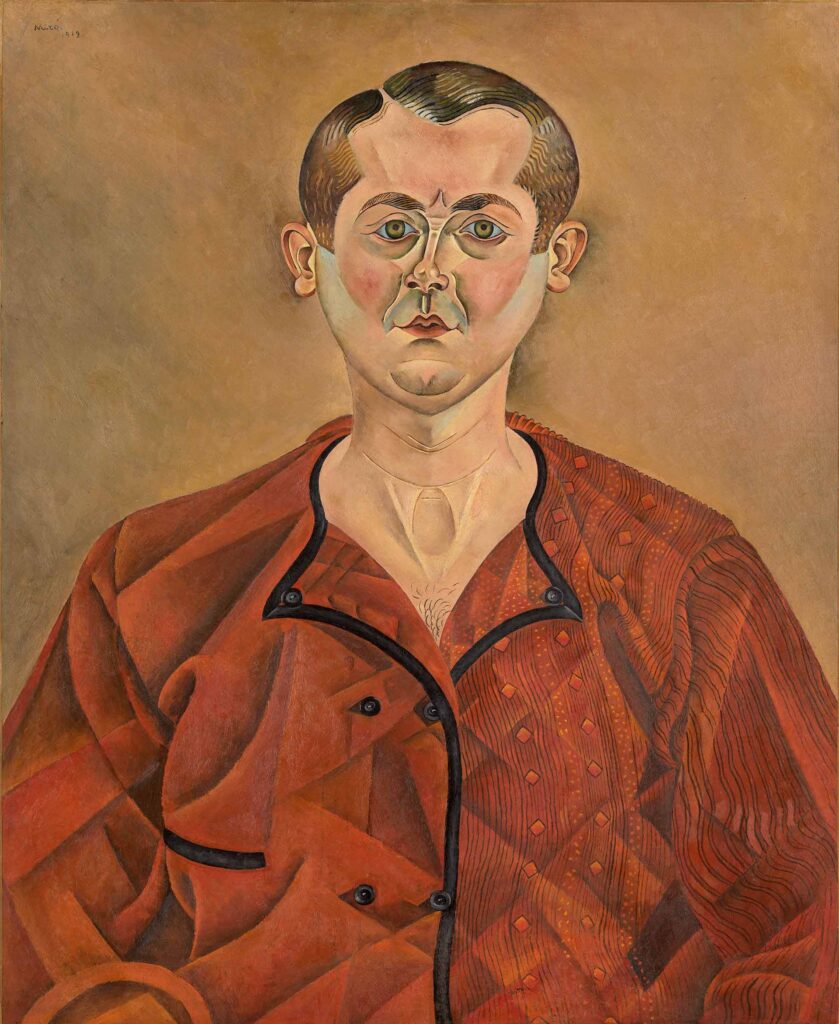

Joan Miró, Self-portrait, 1919, Oil on canvas. Musée Picasso, Paris, France

In 1921, Miró inaugurated his first long-awaited exhibition in Paris, featuring the painting finished in 1919, Self-portrait. Interestingly, this painting by Joan Miró was already part of Pablo Picasso’s collection, marking the early interweaving of their artistic trajectories.

Interestingly, this painting by Joan Miró was already part of Pablo Picasso’s collection, marking the early interweaving of their artistic trajectories.

Pablo Picasso, The Kiss, 1925, Musée National Picasso-Paris, Paris, France.

Their Catalan connection created a cultural bond that went beyond mere geography. Both artists navigated the surrealistic currents of Paris, each becoming associated with the Surrealist movement itself. Picasso’s intermittent involvement and Miró’s exploration of subconscious realms showcased their shared interest in pushing artistic boundaries.

Miró’s 1922 move to Rue Blomet intensified ties with the surrealists. Picasso, never an official member, linked with surrealism through bold, unsettling works like El Beso. Shared explorations of visual boundaries shaped both artists. In short, their friendship and artistic exchange fueled innovation and challenged norms in the dynamic art scene of 1920s Paris.

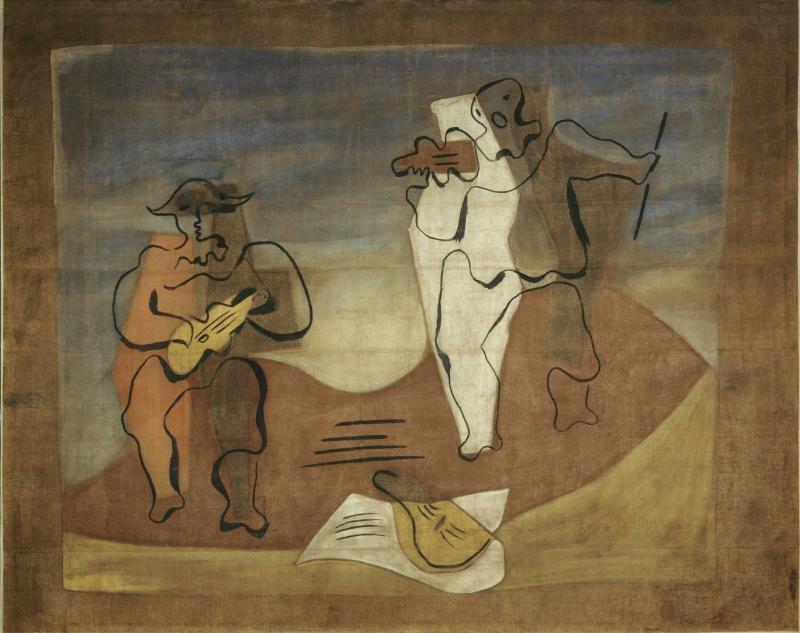

Pablo Picasso, Rideau pour le ballet “Mercure”, 1924, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France © Succession Picasso

In 1924, Miró’s artistic trajectory took a significant turn, marked by his distinct response to Cubism and his evolving relationship with Picasso in particular. One of the main reasons was the premier in Paris of the avant-garde ballet Mercure, which became a significant influence on the surrealists. Picasso designed both the set and costumes, unveiling a new stylistic facet of the Malaga-born painter. The ballet premiered on June 15, just a day before Miró returned to Catalonia for the summer. Ultimately, all of this influenced Joan Miró’s conception of the anti-painting.

Pablo Picasso, The Three Dancers, 1925, Tate Gallery, London, UK © Succession Picasso/DACS 2023

The canvas of their friendship bore witness to iconic artworks that defined their individual legacies. Picasso’s The Three Dancers and The Kiss, and Miró’s Horse, Pipe and Red Flower showcased the convergence of their artistic sensibilities. Another important aspect of those years was the impact of Alfred Jarry, a surrealism pioneer who resonated differently in Picasso and Miró’s works, adding nuanced layers to their artistic expressions.

In the particular case of Three Dancers, this piece unveils a transformative technique, showcasing distorted figures, bold strokes, and a vivid palette. This masterpiece, influenced by personal tragedy, marks a pivotal shift in Picasso’s career and resonates with the emotive essence of the surrealist movement.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain. © Succession Pablo Picasso

The Spanish Civil War became a crucible that united Picasso and Miró in their fight for the Republic. Their joint participation in the 1937 Paris International Exhibition marked a pivotal moment, featuring Picasso’s monumental Guernica and Miró’s El segador. The tragedy of war influenced both artists, as they depicted the iconography of sorrow with deformed faces and expressions of horror.

Joan Miró, Ciphers and Constellations in Love with a Woman, 1941, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

The Second World War put distance between the two friends until 1948. Miró gradually sought to escape reality by creating his own language and began his Constellations series in Varengeville, later completing it in Mont-Roig, Catalonia. Meanwhile, Picasso settled in Royan and Paris during the war’s first year, moving to his Grands-Augustins studio in the summer of 1940. Picasso continued to explore the tragic episodes of both wars through deformed bodies, skulls, and a change in his color palette.

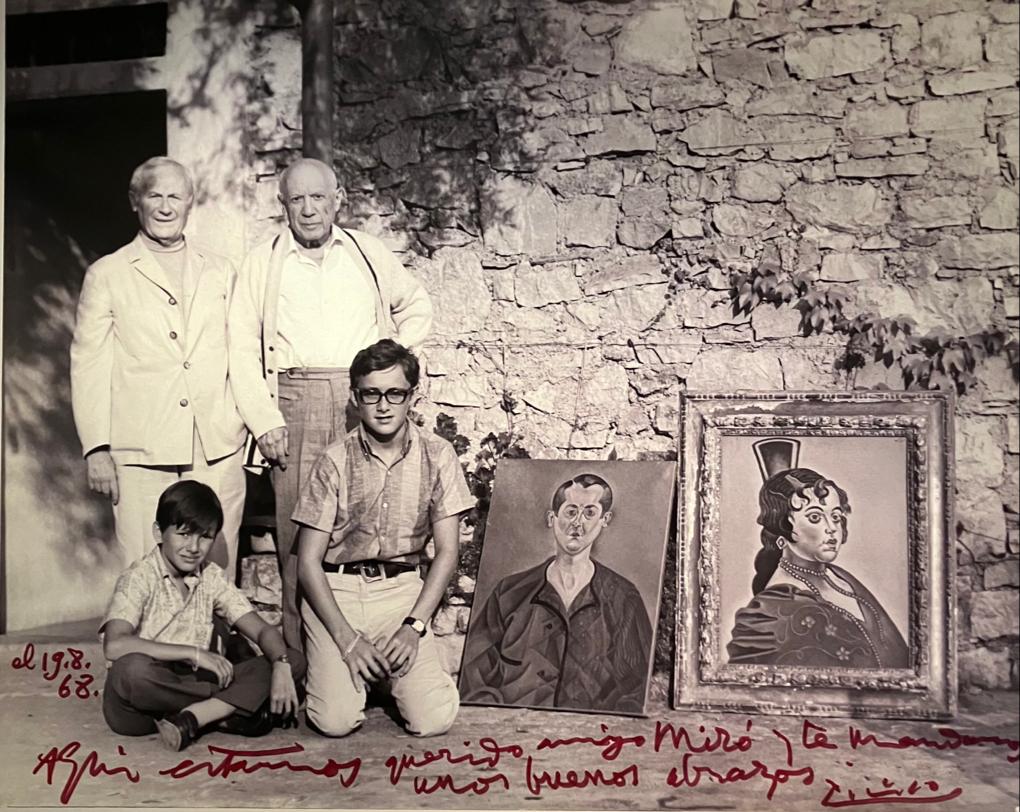

Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso at Mougins, France, in August, 1968.

Miró’s artistic journey evolved over time, embracing a more abstract and symbolic approach, distinct from Picasso’s Cubist tendencies. Despite these differences, they both explored other artistic disciplines such as ceramics and public art. In fact, their friendship blossomed into a profound connection that transcended the realm of art. Picasso, the extroverted and prolific creator, and Miró, the shy and deliberate artist, found harmony in their shared journey.

Miró and Picasso left an enduring legacy in the annals of art history while influencing generations of creators. Despite the variance in their artistic styles, mutual respect underscored their relationship. Undeniably, Picasso acknowledged Miró’s unique vision and contribution to the evolution of modern art.

Despite the variance in their artistic styles, mutual respect underscored their relationship. Undeniably, Picasso acknowledged Miró’s unique vision and contribution to the evolution of modern art.

Miró-Picasso Exhibition, Picasso Museum Barcelona, Spain, Photo credit: Miquel Coll.

This profound artistic journey finds its culmination in the Miró-Picasso exhibition (19 October 2023 – 25 February 2024), a collaboration between the Joan Miró Foundation and the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. Furthermore, the exhibition commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death and the fortieth anniversary of Miró’s.

Comprising 266 works, including paintings, sculptures, objects, graphic works, and drawings, the exhibition unfolds in thematic and chronological blocks. Curated by Teresa Montaner, Sònia Villegas, Margarida Cortadella, and Elena Llorens, the showcase offers a unique perspective into the shared artistic journey of Miró and Picasso.

Joan Miró, Le balcon, Baix de Sant Pere, 1917, Miró Foundation Barcelona, Spain | Pablo Picasso, El passeig de Colom, 1917, Picasso Museum, Barcelona, Spain

The exhibition not only highlights the artists’ connection to Barcelona, but also emphasizes the museums they left as part of their lasting legacy. From the premiere of Picasso’s ballet Parade in 1917 at the Gran Teatre del Liceu to joint exhibitions and shared projects, Barcelona served as the backdrop for their enduring friendship.

In the hallowed halls of the Fundació Joan Miró and the Museu Picasso, the Miró-Picasso exhibition stands as a testament to the transformative power of friendship and artistic exchange. As patrons wander through the curated masterpieces, they witness the echoes of a friendship that transcended canvas and pigment, leaving an everlasting imprint on the canvas of art history.

Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró en Mougins, in 1967, © Sucesión Pablo Picasso

MINK Janis, Joan Miró: 1893-1983, Taschen, 2000

AA. VV., Miró – Picasso, Fundació Museu Picasso de Barcelona (Editorial Museo Picasso), 2023

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!