Marian Henel—Tapestries and Madness

Marian Henel’s tapestries are huge. The largest one measures over 6 m in length and 3 m in width (19 ft. 8 in. by 9 ft. 10 in.). Created in the...

Zuzanna Stańska 25 November 2024

At the beginning of the 20th century, when Japan started embracing the West and rapid industrialization of almost all aspects of life, Miyatake Gaikotsu (funnily enough, gaikotsu means skull/skeleton in Japanese) was the one who questioned and interpreted the nascent culture of modernization. And he did it using puzzlingly curious postcards.

Miyatake Gaikotsu, an essayist, cultural animator, and director of various color magazines, quickly became famous for satirizing the political establishment and the government in his magazines. His parodies earned him fines, kidnapping (!), and even short stays in prison (including the so-called ‘preventive’ ones, whenever the Emperor would leave his Palace, Gaikotsu got arrested – just in case). He derided the censorship by publishing books such as A Story of Prohibited Publications, which in 1911 was even translated into English, or A Collection of Alternative Terms for Naming a Courtesan. As you can imagine, many of the terms were far from euphemistic…

In 1901 Miyatake Gaikotsu launched Kokkei Shinbun (Humoristic Journal), a biweekly with a kaleidoscopic collection of jokes and humourous drawings, some with just a simple objective to make the readers laugh, others with a subversive twist, or with overt sexual innuendos. The journal turned out to be a success, reaching 80,000 copies published per issue. But the real blockbuster was still yet to come.

When Japan won the war against Russia in 1905, tourism within the country took off again, and subsequently, the market for postcards rose in popularity. Gaikotsu seized the momentum and began publishing a supplement to his Humoristic Journal. Measuring 94cm x 64cm, if bent correctly, would result in 8 pages containing 30 different postcards in total. Between 1907 and 1909, the Journal released over 780 postcards. Many readers would later cut them out and send them to friends, others would mail protest letters to the publishing house, complaining about the obscure meaning of the images. How come?

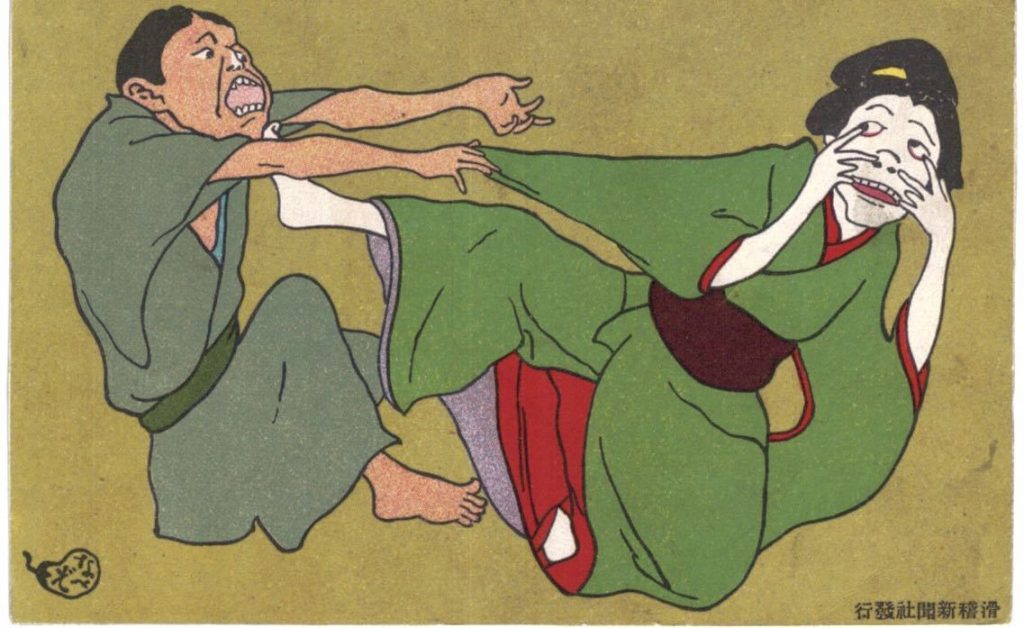

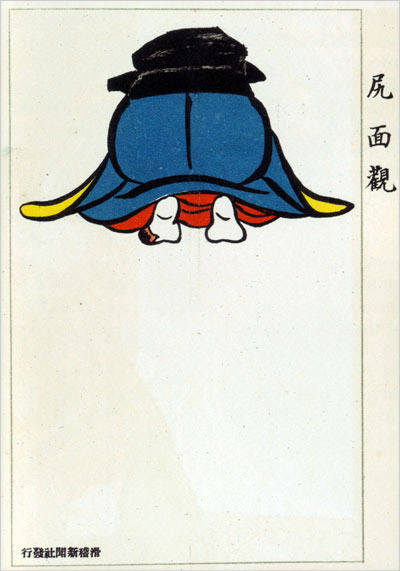

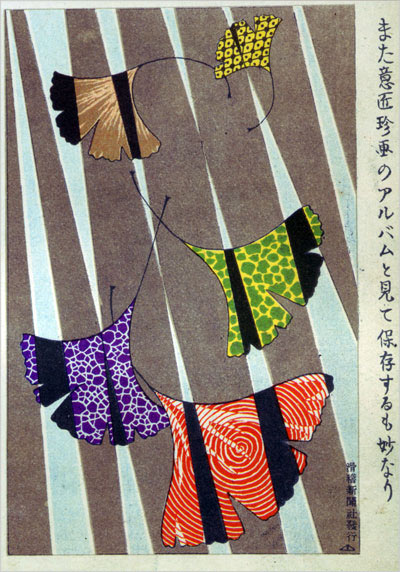

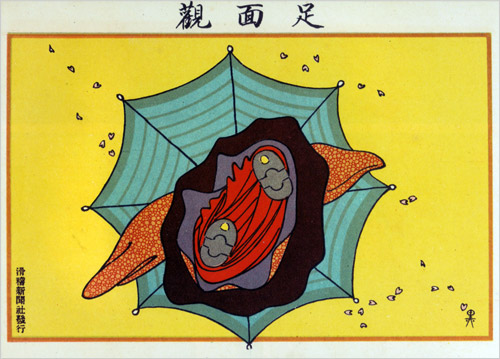

Because Gaikotsu did not publish customary postcards with tranquil landscapes, pretty ladies, or Kabuki theatre actors. Rather, on the contrary, his images were puzzles whose accompanying annotations (usually found on the right-hand side of the image) instead of providing a key to interpretation, rendered the whole thing even more enigmatic. A pair of hairy legs? A woman picking her nose? A girl licking an old man’s bald head? In Gaikotsu’s postcards, curious and bizarre mixed with ordinary and ludic, which, inserted within a traditional Japanese lack of perspective and flat color scheme, all resulted in an extreme level of visual and mental abstraction. And contrary to Europe, where abstraction was a means to reconstruct the universe, Gaikotsu used the limited formal elements just for the sake of making the readers laugh.

The graphic designers of the postcards (anonymous to us but precisely selected by Gaikotsu who would discuss with them new themes for the supplement in the baths) purposely made them difficult to decipher by playing with forms and words, but always making them enjoyable on a formal level, stunning with unusual geometric cuts and surprising with color (look at the postcard above, can you tell what it shows? It’s a woman with an umbrella seen from the ground!). An epitome of this pioneering abstractionism is an all-black postcard, printed a decade before Alexander Rodchenko’s Non-Objective Painting no. 80, Black on Black (1919). Yet, I won’t tell you what it meant, try to guess yourselves.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!