Blood in (and as) Art

One of the first known expressions of human creativity, the Lascaux cave paintings, were created with blood, a material that has remained significant...

Kaena Daeppen 10 June 2024

Let’s delve deep into the dark world of art forgeries! From ancient times to the present day, faked art has reached the art market and fooled many buyers. Over time, the techniques of counterfeiting have improved and the line between original and copied has become very thin. So what are the most famous fakes in art history? What was the purpose and motive of the forgers?

The art of forgery is as old as art itself. Art forgeries can imitate anything from paintings, sculptures, and prints to textiles and furniture. What pushes people to fake art in the first place? The money. The copies of the most famous paintings or artworks falsely attributed to great masters sell for staggering prices.

The evolution of technology has had both advantages and disadvantages when it comes to fakes. Firstly, it has helped forgers because it has helped to develop certain techniques that make forged artwork look more veridic. For example, there are chemical processes that can age the painting material. On mere analysis, this might go unnoticed. On the other hand, if the technology is used by well-intentioned people, it can help uncover fakes, as we will see throughout this article.

Portrait of a Man in a Blue Cap is a 15th-century work by one of the most influential artists of the Northern Renaissance, Jan van Eyck. It is kept in the Brukental National Museum in Sibiu, Romania. The painting was bought by Samuel von Brukenthal in the 18th century as an Albrecht Dürer, as it has Dürer’s monogram and the year 1490 added. A century later, art historians began to question the painting’s true provenance.

Thus in the 19th and 20th centuries, two camps emerged, those who supported the idea that the portrait was a Van Eyck and those historians who rejected the attribution. In 1894, the art historian Theodor von Frimmel attributed the work to the Flemish painter. The historian based his expertise on style, noting the resemblance to another work by Jan van Eyck, Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?). He also claimed that Albrecht Dürer’s monogram and the date were added in the 18th century. The reason the forger added a fake monogram could be that Dürer was selling for more than van Eyck at the time.

Jan van Eyck, Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon, 1430, Brukenthal National Museum, Sibiu, Romania.

Von Frimmel’s discovery was important because it brought a new perspective on the attribution of the painting. On the other hand, not all historians agreed with it. Erwin Panofsky considered the painting clumsily made enough to be with truly attributed to the Flemish master and that it was most likely painted by a follower of Jan van Eyck. In the end, it turned out that Theodor von Frimmel was right. In 1991, the painting was restored and at the same time subjected to infrared examination. This analysis showed that both the drawing and how it was painted are extremely similar to other works attributed to Van Eyck.

Jan van Eyck, Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?), 1433, National Gallery, London, UK.

One of the best-known art forgeries of the 20th century is the Dutch painter Han van Meegeren. He sold his painting Christ and the Adulteress to one of the important men in Nazi Third Reich, Hermann Göring, as an original by Johannes Vermeer. However, after the Second World War, when Van Meegeren was accused of collaborating with the Nazis because he allegedly sold them valuable paintings, he admitted that the paintings were fakes. This saved him from the capital sentence that the Nazi collaborators received. Van Meegeren painted more fake Vermeers, one of them being The Supper of Emmaus, which art historian Abraham Bredius said is the perfect painting of Johannes Vermeer. Moreover, during the trial for selling forgeries, Han van Meegeren stated that his goal was to prove to critics and specialists, who did not offer him validation, that he was a real artist. Thus, by the fact that his paintings were truly considered original works of Vermeer, van Meegeren showed his amazing talent to the world.

Han van Meegeren, Christ and the Adulteress, 1942, Museum de Fundatie, Zwolle, The Netherlands.

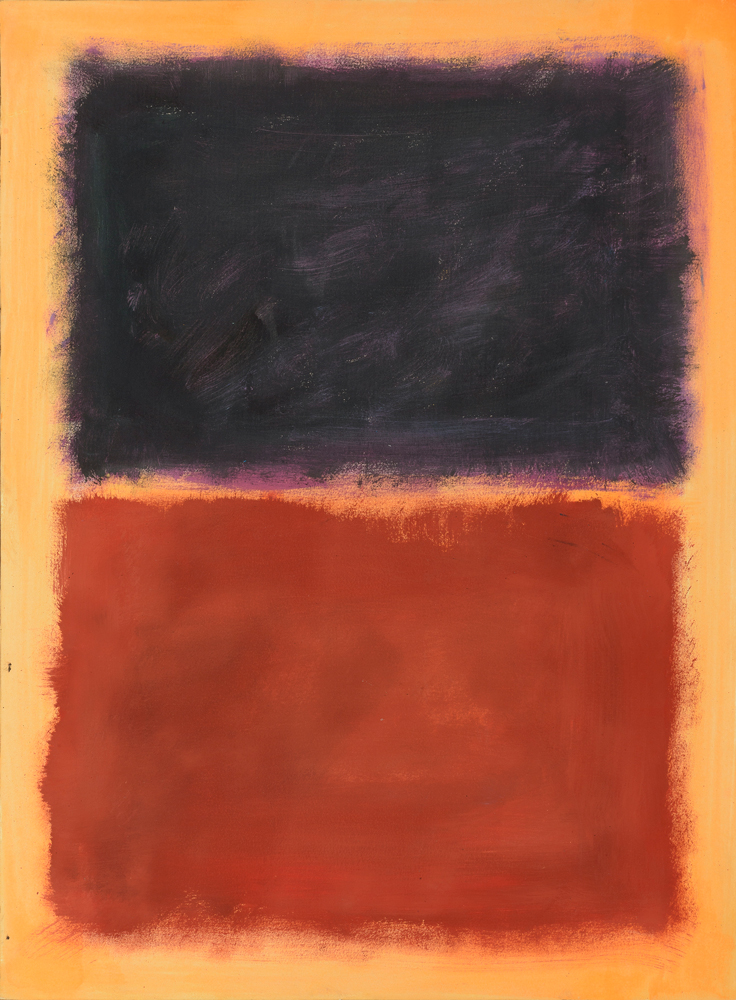

Knoedler Gallery was a prestigious New York gallery that unknowingly sold art forgeries. In 2011, some of their buyers accused the gallery of selling fakes by Abstract Expressionists such as Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. The gallery bought the works from an art dealer, Glafira Rosales, but did not subject them to an authentication process. Gallery’s employees trusted Rosales, who said the works belonged to an anonymous collector. What’s more, they made nearly $80 million from selling the fakes. Eventually, it turned out that all the artworks were forgeries, painted by a Chinese professor named Pei-Shen Qian, who worked with Glafira Rosales. As a result of the scandal, the gallery was closed and the dealer had to pay over $80 million to the victims who bought the art forgeries.

Pei-Shen Qian, Painting in the style of Mark Rothko. Courtesy of Luke Nikas/the Winterthur Museum. Artnet.

Now, let’s delve into the tale of a (quite literally) legendary art forger, Yves Chaudron. It’s crucial to note that the sole source documenting this forger is a single article penned for the Saturday Evening Post. This article unraveled the narrative surrounding the infamous theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. According to the account, the purported thief, Eduardo de Valfierno, allegedly colluded with the forger Yves Chaudron to craft replicas of the Mona Lisa, passing them off as originals, while the authentic painting remained concealed.

However, beyond this article, there exists no substantiating evidence of this forgery or even the existence of Yves Chaudron. Ultimately, the Mona Lisa was restored to the Louvre in 1913.

The empty place of the Mona Lisa at the Louvre after the theft in 1911. Wikipedia.

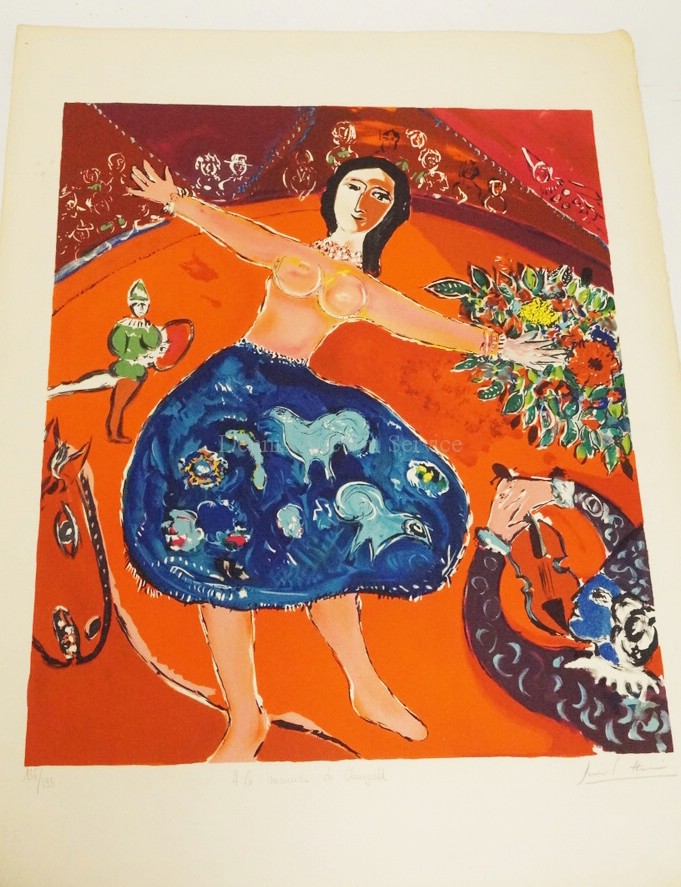

David Stein was a 20th-century art forger and art dealer. He sold copies of the artworks of most known artists as originals. Among the names he sold were Chagall, Braque, Matisse, Paul Klee, etc. In the 1960s, he sold some watercolors with fake authentication certificates attributed to Marc Chagall.

Stein painted these fake watercolors the same day he sold them. The fraud was quickly revealed, however, as the art dealer who bought the paintings met on the very same day with Chagall himself. To his surprise, the artist admitted the new purchase was forged. Eventually, David Stein was reported to the police, arrested and later sentenced to prison.

David Stein, Woman and Circus in the manner of Marc Chagall. Invaluable.

Rita A. Scotti: “The Lost Mona Lisa: The Extraordinary True Story of the Greatest Art Theft in History”, WF Howes Ltd, Leicester, 2009.

John Godley: “Master Art Forger The Story Of Han Van Meegeren”, Wilfred Funk, New York, 1951.

Colin Moynihan: “Suit Against Knoedler Gallery Over Fake Rothko Continues After a Settlement”, The New York Times, 9 February 2016. Accessed 22 Nov. 2023.

Frank Arnau: “Art of Forgers – Forgers of Art”, Econ Verlag GmbH, Dusseldorf, 1959.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!