Andreas Gursky’s Rhine is an interesting piece that tells the transformation of a real-life picture into an abstract work of art. The move towards abstraction in painting has taken a long time ago, but it is not common yet in photography.

Before we get on to the abstract vision, let us first describe what we see in the picture. The river Rhine flows between strips of grass, the shore and a narrow path. The landscape is set under an overcast sky. Gursky captured the image while he was jogging outside of Düsseldorf, trying to distract himself from his work. But apparently, he couldn’t let go of his photographic work; the artist’s mind never stops working.

The first thing you might notice is the horizontal pattern and the monochrome colors. That is because the artist has removed quite a few details from the original picture, using digital editing. He washed away dog walkers and industrial buildings to achieve a clean image. Though he didn’t take away all details. When you take a closer look, you can’t miss the paper or white plastic that has been left behind in the grass. I wonder why he didn’t edit these details away.

Because of the straight bands and the empty impression, the picture feels like an abstract composition. It reads like a horizontal version of the abstract paintings of Barnett Newman. Newman favored vertical compositions with straight lines in a contrasting color interrupting the monochrome surfaces of his canvases. Nevertheless, Gursky’s image is instantly recognizable as a landscape.

Why did Gursky want to make an abstract picture?

So why did he want to edit the picture? His own explanation is that he wanted to strengthen the image of the river that he had in his head. In other words, he wanted to purify the landscape to its essentials. After the editing, he produced a very large color print of the photograph, mounted it onto acrylic glass, and then placed it in a frame. By up-scaling the image to a large format, the essential of the image of water flowing in a straight line becomes obvious. You might translate the image into movement or even progress.

A few years later, Gursky made a variant of this picture and named it Rhine II. It is the same setting and the artist employed the same editing. The difference is in the print formats and of course the atmospherical difference of the specific day that the photograph was taken (the clouds in the sky, the blades of grass – to be found with a magnifying glass).

A lot of money

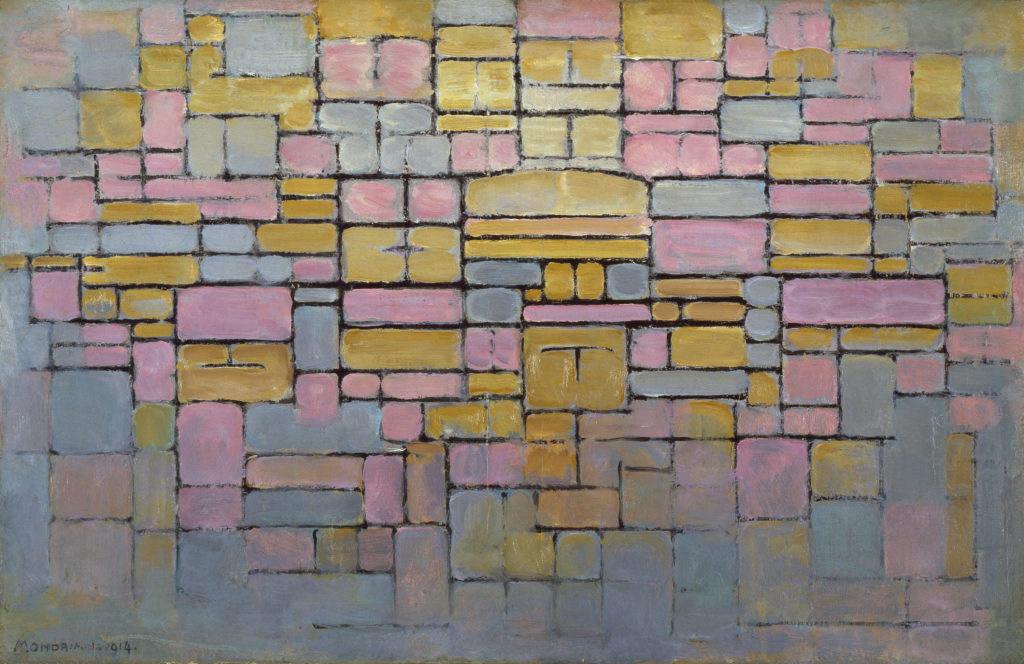

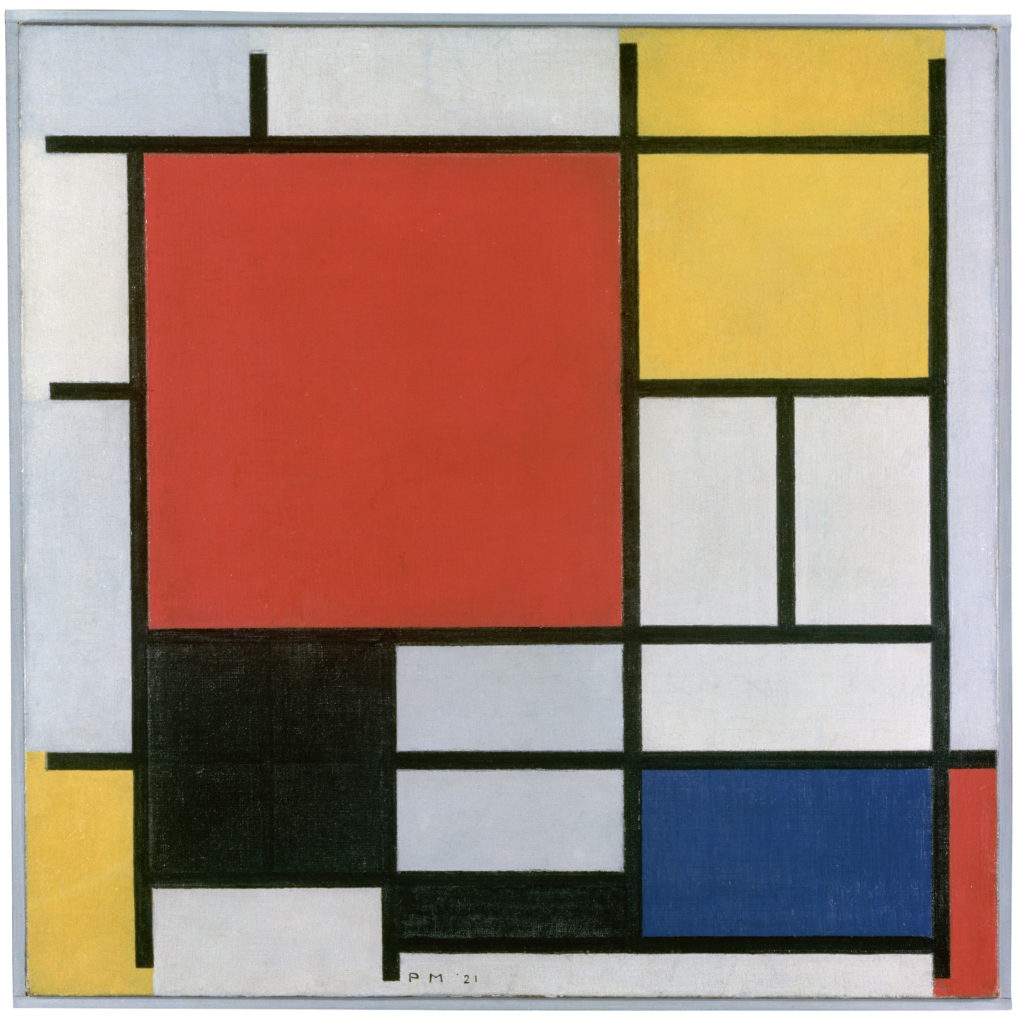

Gursky was not the first artist to make the move to abstraction, but he is a pioneer in photography. Piet Mondrian, famous for his series with colored squares, did the same in painting when he gradually made abstractions of his painted tree from 1908 to 1921. Gursky’s move to abstraction is thus considered a milestone in photography. That explains the high price paid for Rhine II in Christie’s auction in New York: $4.3 million, making it the most expensive photograph ever sold up to now. An anonymus collector purchased it. But don’t worry, if you want to see Rhine II for yourself, you can still see one of the other 5 editions of the photograph at the MOMA in New York and the Tate Modern in London.

-

Piet Mondrian, Evening Red Tree, 1908-1910, Town Museum, The Hague, The Netherlands -

Piet Mondriaan, Blossoming Apple Tree, 1912,Town Museum, The Hague, The Netherlands -

Piet Mondriaan, Tableau nbr 2, Composition nbr V, 1914, MOMA, New York -

Piet Mondriaan, Composition in red, yellow, black, grey and blue, 1921, Town Museum, The Hague, The Netherland

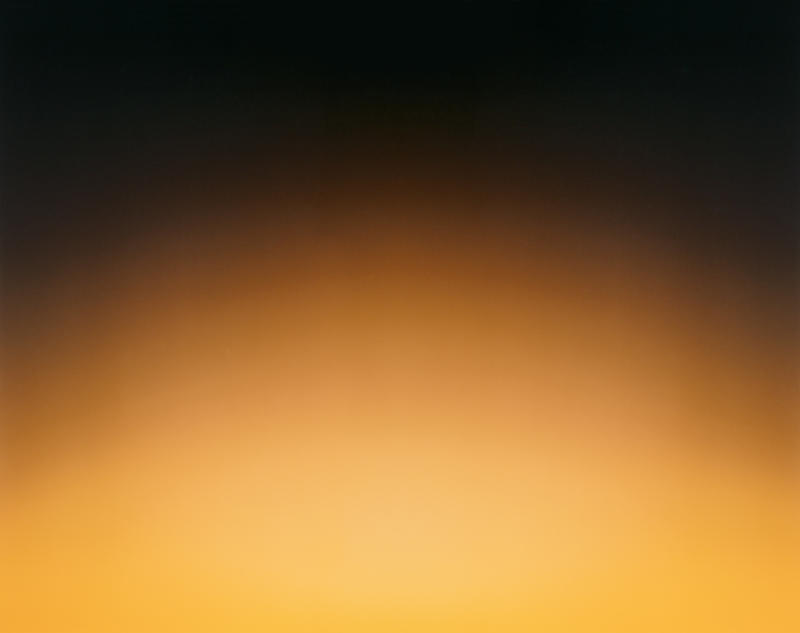

Gursky took some quite abstract photographs. Rhine I and Rhine II are the most interesting ones because they capture the evolution from a figurative to an abstract work in the same photograph. Another example is his work Untitled II, which depicts a sunset.

Gursky’s influences

Andreas Gursky (born in Leipzig, East Germany in 1955) has been influenced by both his father, who possessed a photography studio, and his famous teachers Hilla and Bernd Becher, who are much appreciated for their collection of pictures of industrial machinery and architecture. Their way of working is very systematic, even mechanical, without any personal emotions. This is something that you might recognize in other German artworks. Gursky also demonstrates a similarly methodical approach in his own larger-scale photography.

Barely one year old, his parents fled from East Germany towards the West and ended up in Düsseldorf. He spent his childhood in his father’s studio, where he started to become familiar with photography

He remains a photographer and is currently professor at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf.