Muḥī al-Dīn Muḥammad was the sixth man to ascend to the Mughal throne and the last of the strong Mughal rulers. He was a notable expansionist under whom the Mughal Empire ruled almost all of the Indian subcontinent. On the throne, he was known as Aurangzeb (Persian for “Ornament of the Throne”) or Alamgir (conqueror of the World). Unfortunately, what he possessed in military prowess, he lacked in open-mindedness. His fanaticism and tyrannical tendencies marked the beginning of the slow decline of the golden Mughal reign and of the arts.

Period of Decline

Aurangzeb was more orthodox and austere than his predecessors, and his increased religiosity is reflected in the artworks produced during his reign. While Islamic calligraphy and handmade textiles continued to thrive, overall, there was a significant decline in the artistic realm. This was due to a change in focus and budgetary constraints brought about by constant rebellions and frequent skirmishes with neighboring powers.

The royal atelier (workshop) was also disbanded during Aurangzeb’s reign. Many of the royal artists sought the patronage of the nearby Rajasthani courts and European travelers in India (giving rise to the Company School).

Young Alamgir

Alamgir believed that the Mughal leaders who had come before him were complacent hedonists who had led lives of luxury and decadence. Aurangzeb, however, was a rigid Puritan with orthodox views, a serious-minded young man with natural military prowess. He shared an early rivalry with his eldest brother, Dara Shikoh, the rightful heir to the Mughal throne.

Usurper of the Delhi Sultanate

Aurangzeb eventually overthrew his eldest brother in 1658 and confined his father, Shah Jahan to his own palace in Agra. It is believed that Shah Jahan spent the remainder of his days looking at the Taj Mahal, the tomb of his departed wife, Mumtaz Mahal. After spending years in confinement, he was laid to eternal rest beside his wife in 1666.

Aurangzeb’s Reign

Aurangzeb was considered a capable, though ruthless general. In the early half of his almost 50-year reign, he adopted the strategy of his great-grandfather Akbar. He reconciled with his vanquished enemies by placing them into the imperial service of the Delhi sultanate.

In around 1680, Aurangzeb left northern India to live in the Deccan. This marked a turning point in his reign. His fanaticism started to erode the era of communal harmony and secularism that had been fostered since Akbar the Great. He instituted increasingly puritanical regulations to enforce a rigid Islamic ideology. The jizya tax on non-Muslim subjects that had been abolished by Akbar was reinstated. Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist idols and temples were destroyed. Hindu practices and traditions were forbidden in Mughal courts and the Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur was executed for refusing to embrace Islam. A significant amount of discontent grew amongst the religiously diverse population.

In addition to waning public support, Aurangzeb also constantly battled growing discontent at his borders. The seeds for the sunset of the Mughal empire had been sown.

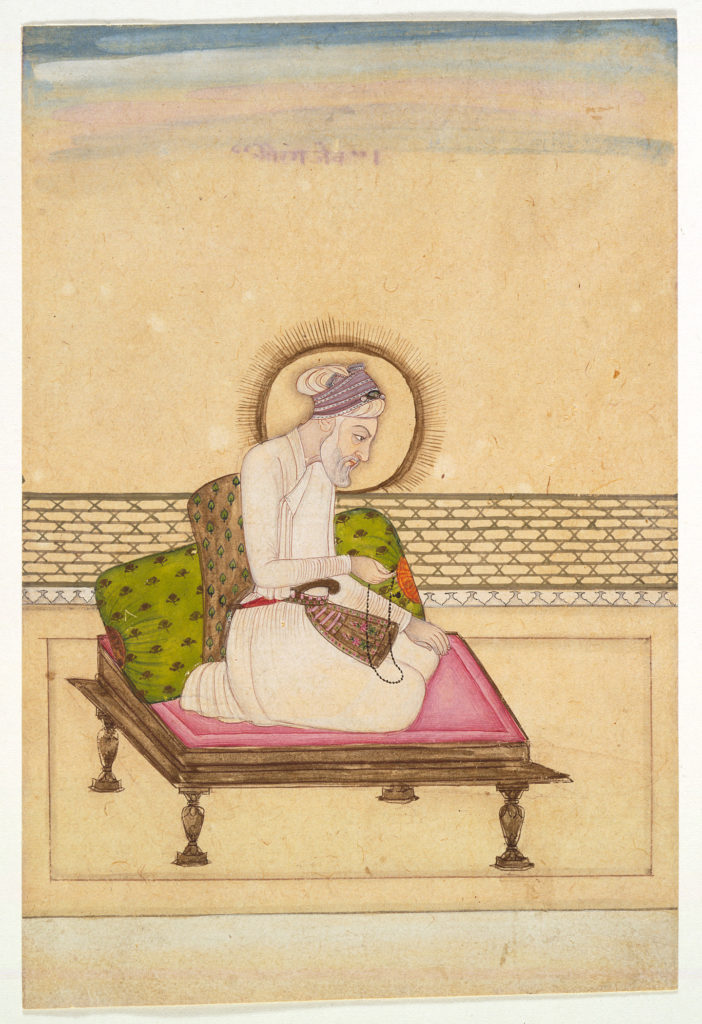

Portraits of Aurangzeb

During Aurangzeb’s reign, there was a shift in artistic style. Instead of the lavish paintings of Shah Jahan’s period, portraiture became simplified and settings were understated. Portraits either represent him as a fearsome warrior in his youth or as an elderly devout Muslim reading the Qur’an.

Islamic Calligraphy & Textiles

The textile industry thrived during Aurangzeb’s reign. It employed hundreds of artisans across South Asia, who created intricate works of silk and brocade. Turbans, carpets, shawls, and other finely embroidered textiles were highly valued. Some were even exported to Europe through trading channels. Aurangzeb also patronized Islamic calligraphy and was himself an accomplished calligraphist.

Architecture under Aurangzeb

Though Mughal architecture followed the same fate as Mughal miniatures, there were some noteworthy commissions under Aurangzeb’s patronage. In this period, brick and rubble with stucco ornamentation replaced the squared stone and marble used in the past. Some of Aurangzeb’s important monuments include Bibi Ka Madbara, a mausoleum for his chief wife which was intended to rival the Taj Mahal (Aurangzeb’s mother’s tomb). The severe budgetary restraints which he imposed, however, resulted in a less grand structure in the Deccan Plateau of India.

Aurangzeb also commissioned the elegant Pearl Mosque in the Red Fort complex of New Delhi, the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore (the largest mosque of the Mughal era), and the Alamgiri Gate of the Lahore Fort. This last iconic monument was once featured on Pakistani currency.

The Disintegration of Mughal Paintings

It is thought that the decline of Mughal paintings resulted from Aurangzeb’s curtailing of state expenditure on the arts. He also discouraged music and dance. The austere Alamgir was disinterested and possibly even hostile to the extraordinary arts created under his predecessors’ patronage. There was a brief revival during the reign of his descendant, Muhammad Shah who shared the more tolerant traits of his ancestors and their passionate devotion to the arts. However, the Mughal treasury was irreparably depleted after Nadir Shah’s sack of Delhi in 1739, and the royal atelier was completely dispersed during the reign of Shah Alam II.

Tomb of the Last Great Mughal

After a long reign and an empire riddled with rebellions, Aurangzeb left the world on March 3, 1707, at the ripe old age of 88. He rejected the aplomb of his predecessors’ grand mausoleums and requested a simple and unmarked grave. His final wish was to be laid to rest close to the dargah or shrine of his spiritual guide, Sheikh Zainuddin in Aurangabad, Central India.

Instead of using funds from the imperial treasury, it is said that during his final years, the last of the powerful Mughal rulers procured his own grave. He did this by selling caps he had knitted himself and by copying the Qu’ran in perfect calligraphy.