A Fire in His Soul: How Paris Changed Vincent van Gogh

In his new book A Fire in His Soul, Miles J. Unger gives us Vincent van Gogh as we’ve never seen him before—abrasive, intransigent, egotistical,...

Ledys Chemin 21 February 2025

To quote the novelist Aldous Huxley “It takes two to make a murder. There are born victims, born to have their throats cut, as the cut-throats are born to be hanged”. If we look at the way in which artists have portrayed murder in art, we could add a third and fourth protagonist to this idea: the artist and the viewer.

Without question, there is a voyeuristic pull towards gazing upon horror and artists throughout history have exploited our grizzly interest in the macabre.

In this work from 1507, Giovanni Bellini shows the death of the Dominican friar Peter of Verona and his companion, Dominic, in the 13th century. A preacher and inquisitor, Peter of Verona was responsible for many converting back to Catholicism. Caught by hired assassins on the road to Milan, the murderers attacked the men as they were returning home.

The brutality of the assassination is reflected in the acts of the woodcutters in the background. It is said that as Peter was bleeding from his wounds, he wrote the words “Credo in Deum” on the ground.

The death of Jean-Paul Marat has inspired many images. The fiery orator of the French Revolution was murdered by Charlotte Corday, a young Royalist who managed to gain entry to Marat’s apartments with the petition that can be seen in his left hand.

His usual practice was to work in his bathtub due to a disfiguring skin disease that he treated through bathing for long periods. Here, Jacques-Louis David portrays the moment after Corday stabbed Marat as he was writing. His friend, Marat is dying. His half-opened eyes, his drooping arm still clutching his quill, and the blood dripping onto the white sheet give this work a sense of pathos that Munch focused on in his work of the same name.

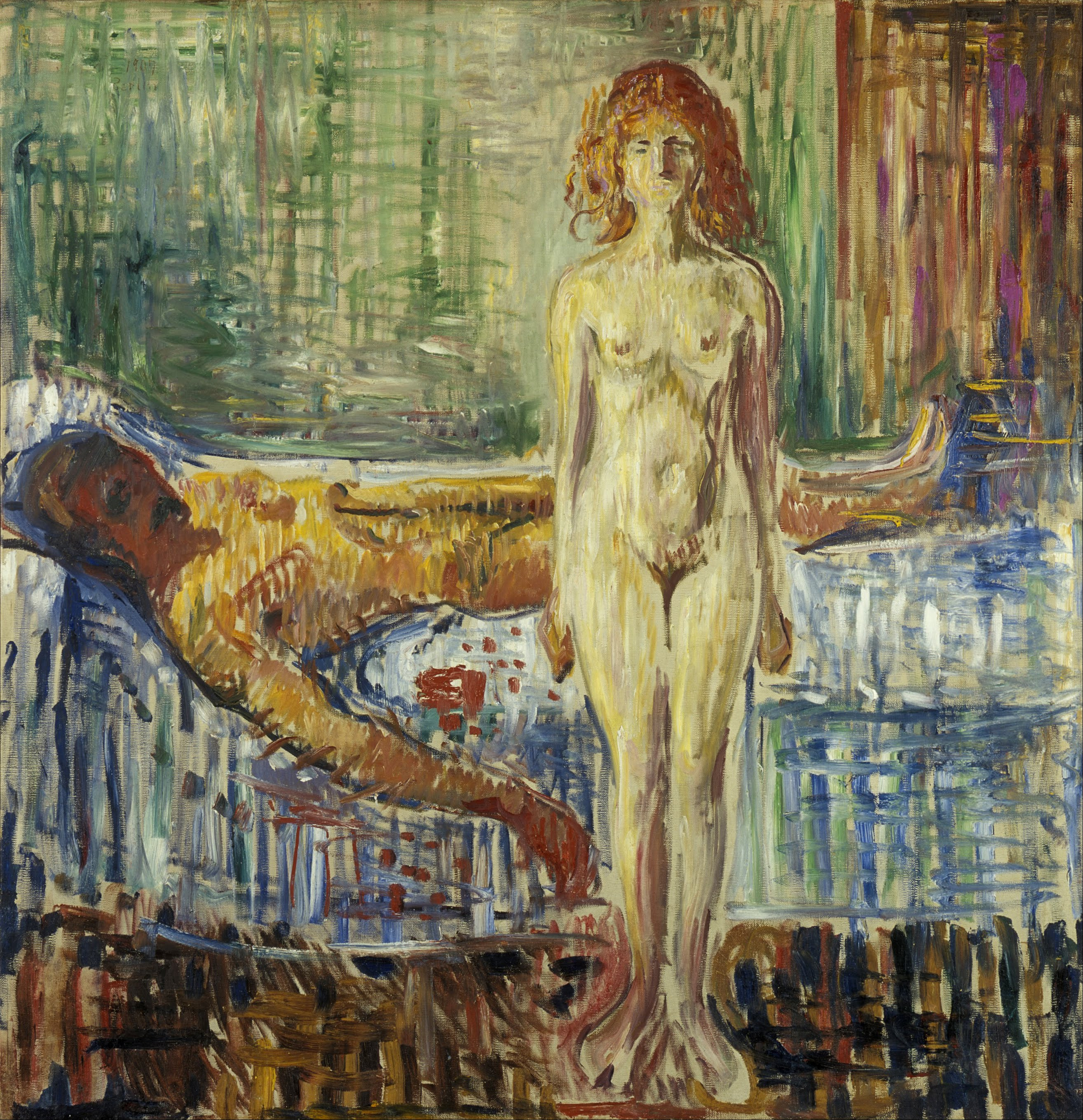

In Edvard Munch’s depiction, he substituted himself and his one-time lover, Tulla Larsen into the roles of Marat and Corday. The focus is on the naked body of Corday/Larsen rather than on the death of Marat/Munch. Inspired by a hunting accident that occurred in front of Larsen where Munch injured two of his fingers, he reveals a shocking brutality with the blood from his injured hand on the sheets and splashed along the legs of Corday/Larsen which contrasts with David’s focus on the gentle expiration of the man. The contrast with David is also apparent when examining the brushwork. Munch’s quick strokes conjure up a scene of devastation and turmoil and clearly is a metaphor for his emotional state at the time of the work.

As I beheld two shadows pale and naked, Who, biting, in the manner ran along that a boar does, when from the sty turned loose. One to Capocchio came, and by the nape seized with its teeth his neck, so that in dragging it made his belly grate the solid bottom. And the Aretine, who trembling had remained, said to me: “That mad sprite is Gianni Schicchi, And raving goes thus harrying other people.”

Canto XXX in Divine Comedy: Inferno by Dante Alighieri.

This beautifully composed work by William-Adolphe Bourguereau portrays the eighth circle of hell in Dante’s Inferno where the imposters and falsifiers reside. Gianni Schicchi who took on the identity of a dead man to gain an inheritance, sinks his teeth into the neck of the alchemist, Capocchio. Dante and Virgil remain in the shadows, horrified by this display of violence. In the background, the devil laughs and jeers at this murderous scene. The power and force of the muscular bodies, with tendons straining and light bouncing off their naked flesh fill the front plane of the composition.

The use of light and shadow plays an important role in this powerful portrayal of murder. Artemisia Gentileschi uses chiaroscuro to great effect as she depicts the moment when Judith, a widow, murders the general Holofernes, who is about to destroy the city of Bethulia.

Many artists have depicted this particular murder on canvas, but it takes a woman to show the brutality in the most realistic way. The maid helps hold his head down however it is Judith who uses her powerful forearms to decapitate the hated general. Blood pours across the sheets and off the edge of the bed but neither woman flinches from this brutal act.

Artemisia Gentileschi had been through a rape case herself, the details of which, unfortunately, often overshadows her work.

In these two paintings, both Paul Cézanne and Walter Sickert portray murder in ways that we recognize only too well today.

Cézanne captures the moment that the final blow is about to be delivered. The brutality of this scene contrasts with the landscapes and still life paintings he is most known for. This early work has a dark tonal quality that puts the viewer in the composition; we peer into the dark to see what is happening. We recognize no one in this painting and the anonymous quality of the characters creates a timelessness to this type of act. The murderer’s accomplice holds the victim down, just as Judith’s maidservant does in Gentileschi’s painting.

In Sickert’s painting, however, the murderer is absent from the scene. Based on a true story, Sickert created a composition that confuses the viewer. The light from the partially opened curtains illuminates the naked body on the bed. At first, we think she is asleep, but her posture, the necklace, the painted lips start to make us uncomfortable. On the chair is a man’s jacket. Does it belong to the murderer? Is he still there?

It seems apt to quote William Shakespeare on the topic, when Hamlet, the eponymous hero, instructs the players to portray the murder of his father, tells them: “For murder, though it have no tongue, will speak with most miraculous organ”. The hand and the eye have much to say on the subject of murder in art.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!