The word “muse” has generally a very positive connotation. People, commonly women, represented under the umbrella of this word are held in very high regard. That is to say, artists who take talent and flair from of their so-called muses believe their sources of inspiration are greatly revered. Nevertheless, the word limits our perception to a very narrow understanding of the impressive and exceptional contributions the “muses” made to many art forms.

Origins of Muses

According to Hesiod, in Greek mythology, “Muses” or “Mouses” were beings who inspired artists and philosophers in the process of creation. As claimed by the Greek myths, the god Zeus slept with a young woman called Mnemosyne, who was the Titan goddess of memory, for nine consecutive nights. Their intimate encounters gave birth to nine muses: Clio, Euterpe, Thalia, Melpomeni, Terpsichore, Erato, Polymnia, Ourania, and Calliope. Μnemosyne, baffled and perplexed, gave the babies to the nymph Eufime and the god Apollo.

As the Muses grew up, they inclined toward the arts and showed not a single sign of having interest in average human life. As a result, Apollo took them to Mount Elikonas (former temple of Zeus) and, in accordance with Greek mythology, ever since that day, Muses have been intensifying curiosity and imagination; helping artists to create masterpieces.

Beyond Myths and Legends

We can encounter the word “muse” very often beyond Hesiod’s and Homer’s writings and find out that it is, in fact, quite common for artists to seek ingenuity, creativity, and inspiration outside of themselves. Often times, we come across an artist whose creative outburst resulted from someone else’s mere presence. However, we repeatedly fail to acknowledge the contributions made by a person who we regard as a muse.

Elisabeth Siddal

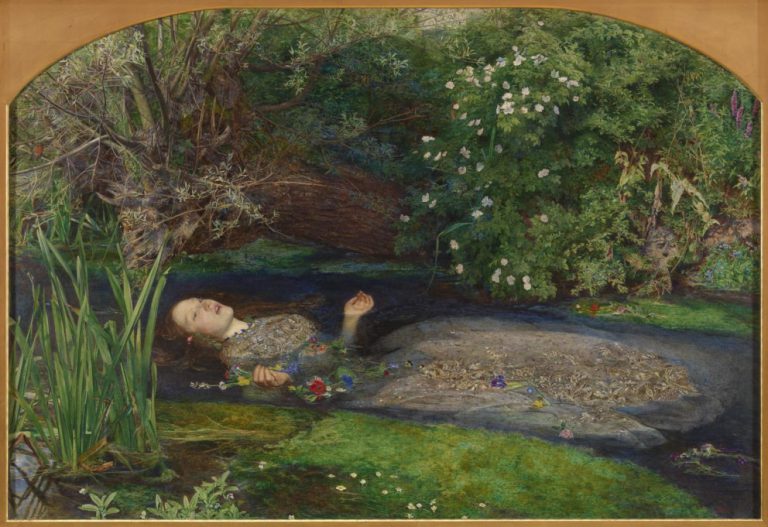

John Everett Millais’ Ophelia is probably the most famous visualization of the epochal character’s death. It is also a painting that almost everyone knows, even those who are not passionate about arts. As time goes by, more and more people learn that an actual woman put almost the same effort in creating this masterpiece as the painter himself.

Elizabeth Siddal (1829–1862), then 19 years old, lay clothed in the bathtub to model for Millais. As it was winter, a deeply absorbed Millais did not notice the warming oil lamps under the bathtub went out. As a result, Siddal caught severe cold and Millais was not very happy about financing her medical expenses. I believe it is apparent that the model put so much energy into creation and actually struggled and suffered much more than the artist himself. This is not to disregard Millais’ immense talent of course. He was the one who physically painted, but Siddal’s contribution is frequently overlooked and reduced as just “modeling” for the acclaimed artist.

Read more about this artwork.

Siddal’s enigma had the greatest importance in the establishment of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics; in its exploration of femininity and feminal sensibility. Above all, the brotherhood is famous for their depictions of a very specific type of women – overly mystified, somewhat free, yet somewhat fettered; protofeminist, yet repressed; vibrant, yet subdued. A woman who has it all to break free; yet men still perceive her as a little too flawed to be a complete person in her own right. Such was Siddal’s life. The paintings of Millias, Hunt, and her husband Rossetti immortalized her.

The sad part is that we mainly remember Siddal as a muse rather than an actual artist, which she in fact also was. Even though Rossetti’s and Siddal’s marriage suffered due to former’s lack of faith and the latter’s drug addiction, Elizabeth learned to paint on her own. She her talent was so great that John Ruskin, the most notable art critic of the era, called her “a genius” and even gave her annual salary of £150 to push her creative energy forward.

After a stillborn daughter and post-partum depression, Siddal, once again, pregnant, overdosed on laudanum. However, today it is widely known that Siddal was a great artist in her own right who produced artistically significant pieces throughout her life. Yet articles, essays, and obituaries still remember her as a “Pre-Raphaelite muse,” or “Muse to Rossetti.”

Victorine Meurent

Victorine Meurent (1844–1927) is another example of dismissing a female artist’s contributions. Almost every piece of writing about her opens with the label – “Manet’s muse”, or “Manet’s favorite model.” Yet it was her self-portrait which was exhibited at famous Paris Salon. Ironically, this was the same venue which rejected Manet’s works. Besides Manet’s controversial Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia, Victorine modeled for Edgar Degas and Alfred Stevens.

It is no wonder why Meurent impressed so many great artists. Her presence is overwhelmingly palpable and substantial on paintings that you feel like you can actually engage yourself in a casual conversation with her; it was, of course, her outré looks that enchanted artists too; she seems so distant, so unearthly, and so bewitching, but she, at the same time, is gentle, delicate, and humane.

We do not know much about Meurent besides the fact that she came from a very hard-working family and she made living as a painter before she injured one of her fingers. Most of her works are now missing. However, from the smatterings of her surviving pieces, we can tell that we lost a great artistic vision.

Camille Claudel

Today there is an entire museum devoted to Camille Claudel (1864–1943) in Nogent-sur-Seine, France. Even the prominent Musée Rodin houses a very specially created room dedicated to her works. However, Claudel died without knowing how artistically significant a sculptor she was; her artworks and contributions were in obscurity as they never saw the light of day during her life.

What Claudel was known for is the assistantship of the highly praised artist Auguste Rodin. Art historians and critics recognize the immense influence Claudel had on Rodin’s work. Despite her massive role in Rodin’s life, he never really tried to give up on his marriage for her. Claudel spent 30 years in a mental ward and she herself destroyed many of her own art pieces as a result of anguish and despair. Unlike Siddal or Meurent, Claudel’s art pieces are under a bigger spotlight, however, it is not enough for her to transcend the label “Rodin’s Muse.”

Dora Maar

Dora Maar (1907–1997) had notoriety and fame during her life as the embodiment of Picasso’s The Weeping Woman. Rumor has it that after catching the glimpse of him on the set of Jean Renoir’s The Crime of Monsieur Lange, Maar was captivated by him. As a result, Paul Eluard introduced them to one another, and their tempestuous affair took off. This enchanting young woman equally intrigued Picasso. It is not a secret that he frequently painted her as sorrowful and tragically sad.

Maar had enough creative parity that she actually depicted the stages of Guernica’s creation which helped Picasso tremendously. This is not all –

she was also an accomplished painter, photographer, and poet. Her works were exhibited numerous times (at places like Centre Pompidou and Tate Modern) in the attempt to showcase her artistic excellence.

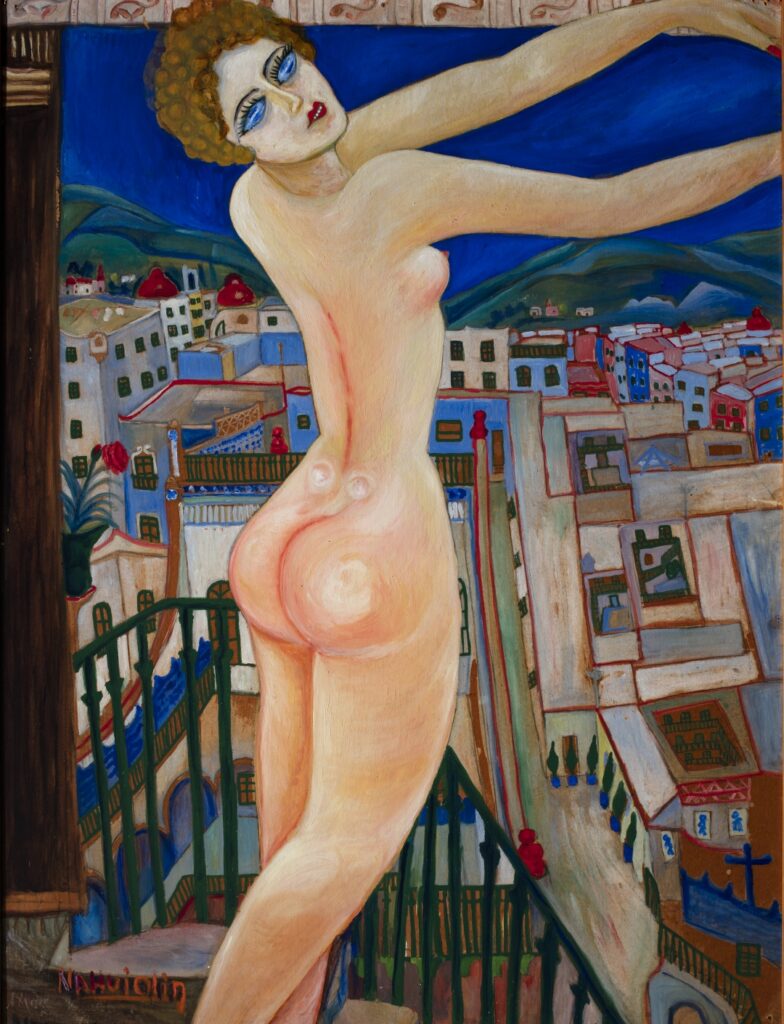

Carmen Mondragón

Carmen Mondragón, aka Nahui Olin (1893–1978), was one of the most prominent figures of Mexican Avant-Garde art but she was mostly remembered as muse. She used to model for Diego Rivera, Edward Weston, and Antonio Garduño. However, the person with whom she formed the strongest creative relationship was her lover – Gerardo Murillo Cornado (Dr. Atl).

Rediscovering her life and art started pretty recently. It turned out that Olin was the secret flavor to Mexico’s sexual revolution. After bewitching great artistic talents with her wispy hair, cartoonish green eyes, and sculpted body, she wrote poems that liberated her own country from prejudices about sexuality and female self-perception for which she gradually became a canonical feminist icon. The National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago exhibited her works in 2007.

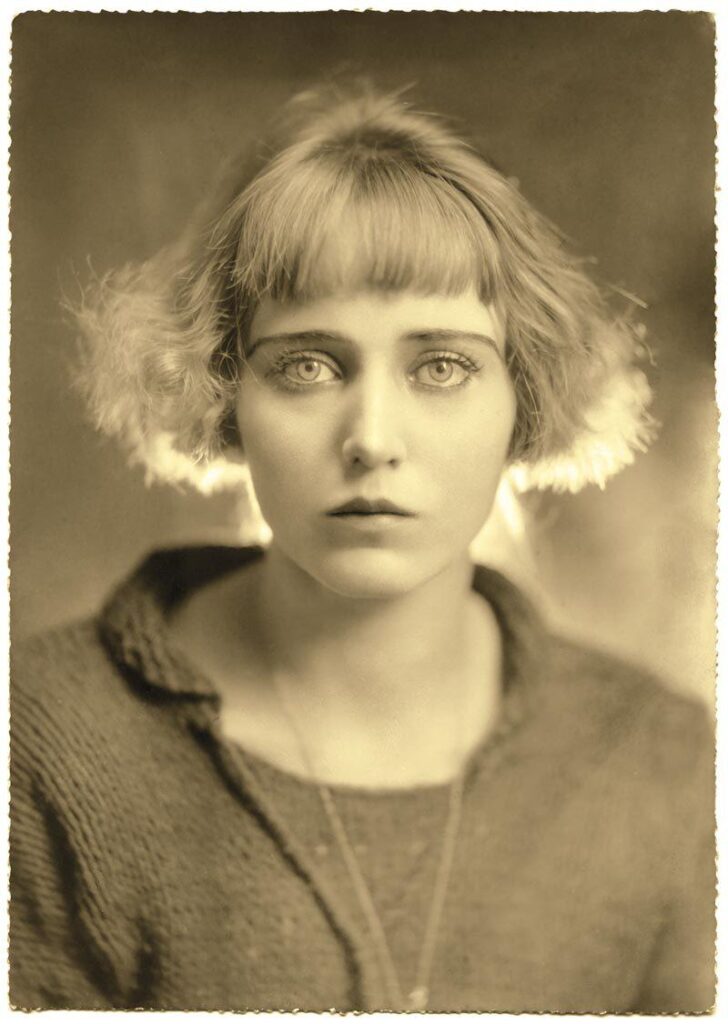

Kiki de Montparnasse

Taking Kiki de Montparnasse’s (Alice Prin, 1901–1953) case into account, we can see how posing and modeling for male artists belies one’s own artistic oeuvre as a female. At the age of 26, she had a sold out exhibition of her paintings at Galerie au Sacre du Printemps in Paris. However, she is mostly remembered as the muse to Man Ray, Amedeo Modigliani, and Alexander Calder.

Not only was she an accomplished painter, but also an actress and memoirist. Her memoir, for which Hemingway wrote the introduction, is the crucial instrument in the understanding of 1920’s Parisian life: its blooming Surrealist circles and burgeoning bohemian culture. Today many art enthusiasts regard her as the most iconic figure of Surrealist-era Paris as her writing and presence shaped entire culture and lifestyle. Yet, Kiki is

not the first person who comes to our minds when someone brings up 1920’s Paris.

Muses in Cinema

In the cases of female painters one might argue that their contributions are overlooked due to the fact that they were not well documented. Yet in the case of film arts, I believe, it is a pretty non-convincing, even ridiculous, argument. Acting is an artistic endeavor in its own right. However, when actresses happen to breathe life into earth-shattering, decade-defining characters, they suddenly become muses; the real force lies behind the camera, a male director who is responsible for the creation of anything admirable, his actress is only a puppet that follows his instructions.

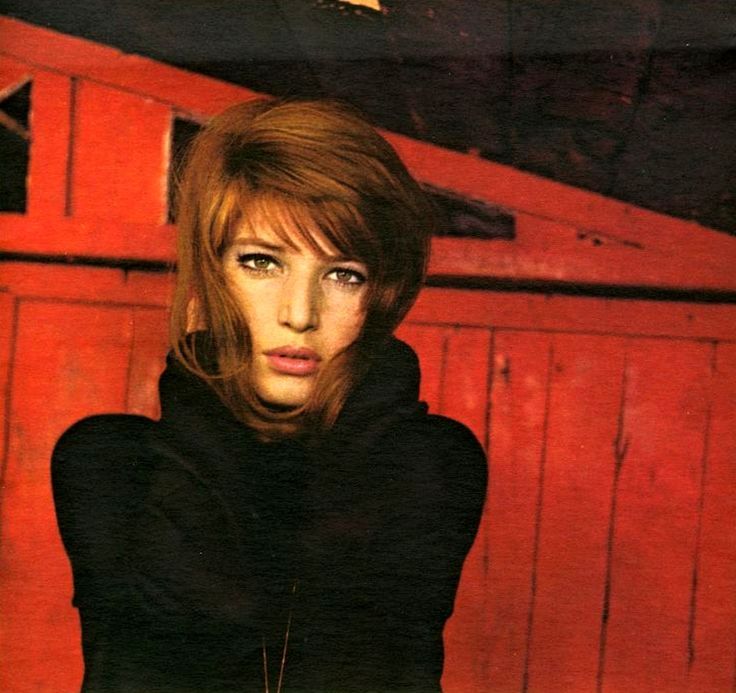

Anna Karina

Anna Karina (1940–2019) and Jean-Luc Godard are among the most famous actress-director duets of all time. Karina’s status has rarely gone far beyond the “Godard’s Muse.” They made eight films (including a segmented film – The Oldest Profession) together and I think it is fair to say that they established a whole new way of storytelling cooperatively. The famous Godardian Pop aesthetic would be nothing without Karina’s acting efforts; it does not matter how Godard experimented with the medium, how he shot, edited, and musically shaped his films, his early filmography would not have the same poise and allure without Karina’s ruminative facial expressions and body language; without her own ability not to make you forget that you are watching a film.

Monica Vitti

The same applies to Monica Vitti (b. 1931) and Michelangelo Antonioni. If Vitti was a lesser actress and she did not possess the ability to translate the contemporary decadence into her own face, Antonioni would never become the epicist of modern-day alienation, but, of course, she is remembered as “Antonioni’s Muse.”

This is just a very small list of artists who have a huge creative legacy, but who are only referred to as helping hands for their male partners or friends. It is apparent that whenever a woman creates something lasting and creatively important, society puts too much effort into dismissing her talents and lowering her status to an enduring classic – Muse.

Author’s bio:

Mariam Razmadze is from the country of Georgia, but she is about to move to Budapest for her studies. She is 19 years old and dreams of pursuing dramatic arts. Some of her creative writing pieces (poetry, short stories) have been published under her pen name which she wants to keep as a secret. Her other writings can be found on Screen Queens and Taste of Cinema. Currently, she is the poetry reader at Flora Fiction Literary Magazine.

Here’s some more stories of More-than-Muses: