The National Gallery in London: Where to Start?

Having lived in London for the past three years as an art lover, I have had more than my fair share of questions about where to “start” at the...

Sophie Pell 3 February 2025

Have you ever been to the Museo Egizio in Turin, in northern Italy? Located in the old town, this institution brings together more than 300,000 pieces, of which 6,500 are on display to the public. Thus, the spectator can admire a large number of sarcophagi with their human and animal mummies, statues, a whole series of papyri, as well as everyday objects, such as furniture or jewelry. All these works are presented in large rooms, accompanied by a lot of information. You might say that you have to take your time to see everything!

Room view, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Viator.

Jean-François Champollion, the famous translator of the Rosetta Stone, affirmed that “The road to Menfi and Thebes passes through Turin.” Museo Egizio in Turin was created in 1824 by King Charles-Félix of Savoy to bring objects from the collection of Paduan Egyptologist, Vitaliano Donati, and archaeological pieces belonging to the House of Savoy together in one place. Through this foundation, Turin is considered the birthplace of Egyptology.

Remember that the Italians were very early interested in what was to become a real science. The Piedmontese Bernardino Drovetti is one of the pioneering figures in this field. Accompanying Napoleon Bonaparte during the Egyptian Campaign (1798-1801), the Consul General of France built up a collection of 8,000 Egyptian antiquities which he sold in 1824.

Another important Italian figure is the archaeologist Ernesto Schiaparelli. He is also the first director of the Museo Egizio in Turin – a post he held for 30 years! He helped develop its collections considerably by enriching the museum with 30,000 new pieces. Later, the museum continued to grow, in particular with the exhibition of archaeological testimonies found during the excavations of the Italian Archaeological Mission. This took place between 1900 and 1935 and a large part of the findings were brought back to Italy.

Room view, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. GetYourGuide.

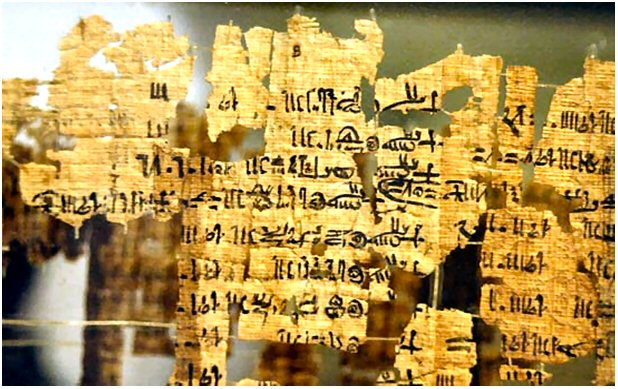

From a historical point of view, the most important work of Museo Egizio is the Royal Canon of Turin. It’s a papyrus written in hieratic (that is to say a simplified hieroglyphic script used in the context of administration). It originally measured more than 2m in height. On the back, it presents a list of 300 rulers who successively reigned over ancient Egypt, along with the lengths of their reigns. Eleven columns of text thus detail the name of a pharaoh, in his cartouche (which acts as a symbol of protection), followed by the number of years composing his reign. Egyptologists have, however, noted certain errors made about too long durations of the oldest reigns. Studied by Jean-François Champollion, this important work is nonetheless one of the major sources of Egyptian history.

The Royal Canon of Turin, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Antikforever.

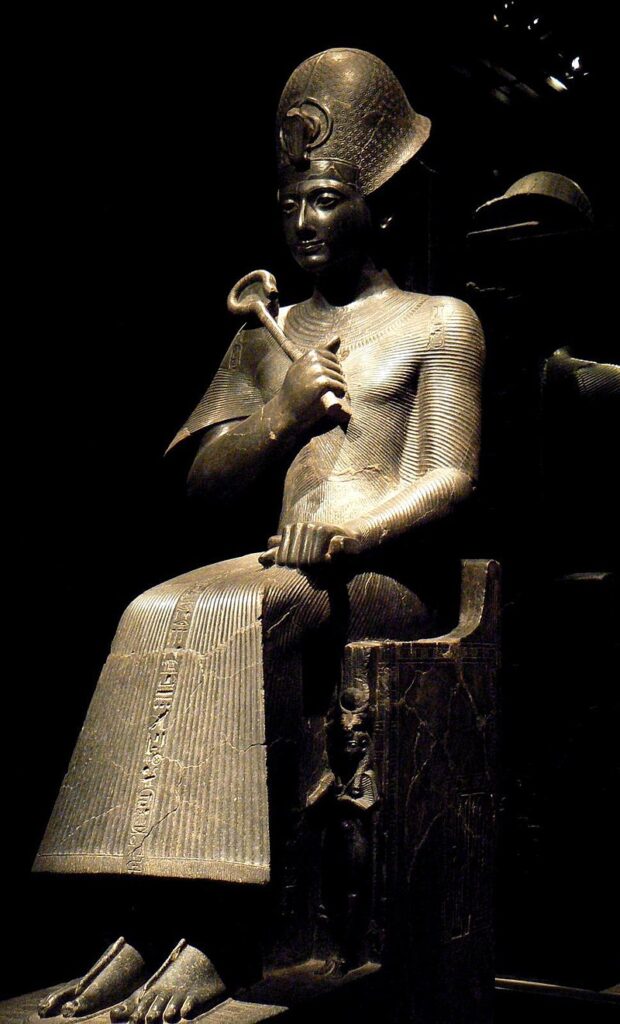

Another masterpiece from the Turin collections is the statue of Ramses II, which dates around 1380 BCE. It was discovered in 1818, in the eastern part of the great temple of Karnak, by Jean-Jacques Rifaud on behalf of Bernardino Drovetti. Made of diorite (a magmatic rock), it represents the famous pharaoh seated on a throne, wearing the kheprech crown (a blue crown, probably symbol of victory, on which the uraeus coils), and holding the heka scepter in his right hand. In the lower part of the throne stands, on the right, a representation of Amonherkhepshef, one of the sons of the great sovereign. Meanwhile, on the left, is a representation of his wife Nefertari, “the beloved of the Theban goddess Mut”. An impression of majestic durability emerges from the work of art. Arriving in fragments in Turin, it was reconstructed with the support of Jean-François Champollion, then visiting the museum during the summer of 1824. Praising “the beauty and the admirable perfection of this colossal figure”, the French Egyptologist would go to confess to be in love with this work.

Statue of Ramses II, diorite, c. 1380 BCE, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

The tomb of the married couple Khâ and Merit is also the pride of the museum. Discovered in 1906 by Arthur Weigall and Ernesto Schiaparelli as part of the Italian Archaeological Mission, the tomb is located in Deir el-Medina, in the Theban necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, facing Luxor in Egypt. Responsible for the works of the necropolis under the kings Amenhotep II, Thoutmôsis IV, and Amenhotep III, Khâ is an important figure in the city of craftsmen. The funerary material kept in his tomb and now exhibited in Museo Egizio testify to the wealth of the couple. Thus, you can admire within the rooms the sarcophagi of the couple, multiple objects with funeral vocation, as well as toilet articles, clothes, and jewelry. Take a special look at the anthropomorphic inner coffin of Khâ. It’s entirely covered with gold leaf, while the eyes are encrusted with quartz or rock crystal for the whites of the eyes, black glass or obsidian for the irises, and blue glass for the eyebrows. His arms are crossed over his chest in the pose of Osiris, Lord of Death. This piece displays the technical mastery of the ancient Egyptians.

Khâ and Merit’s Funeral Material, Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Egyptophile.

Filled with so many other wonders, Museo Egizio in Turin is a place you absolutely must visit. Whether you are an absolute fan of the pharaohs of ancient Egypt or simply a curious person, this famous place is sure to make you travel through time.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!