Who’s the Jester on Lady Gaga’s Harlequin Cover?

Lady Gaga released an exclusive vinyl of her new album Harlequin, and fans quickly pointed out many easter eggs the artist had left on the cover. The...

Sandra Juszczyk 22 November 2024

Music and art have long been closely tied together, each taking inspiration from the other (for better or for worse). Some remarkable music has been inspired by great works of art. For example, Italian composer Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) used as his muse three paintings by Sandro Botticelli (Spring, The Birth of Venus, and The Adoration of the Magi) when composing his Botticelli Triptych: Three Botticelli Pictures for Orchestra.

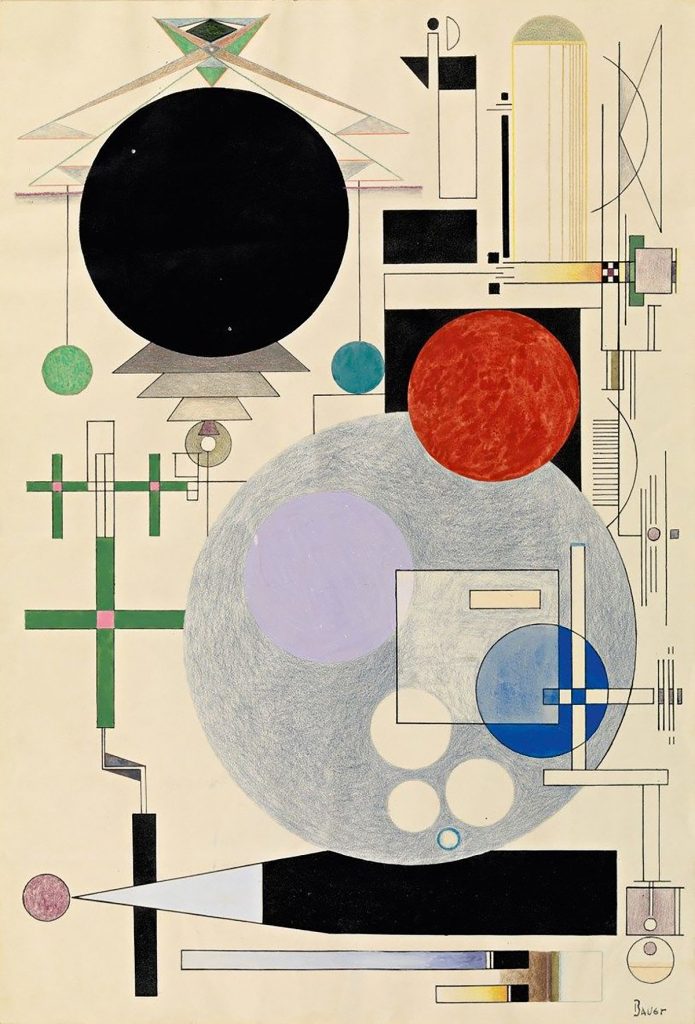

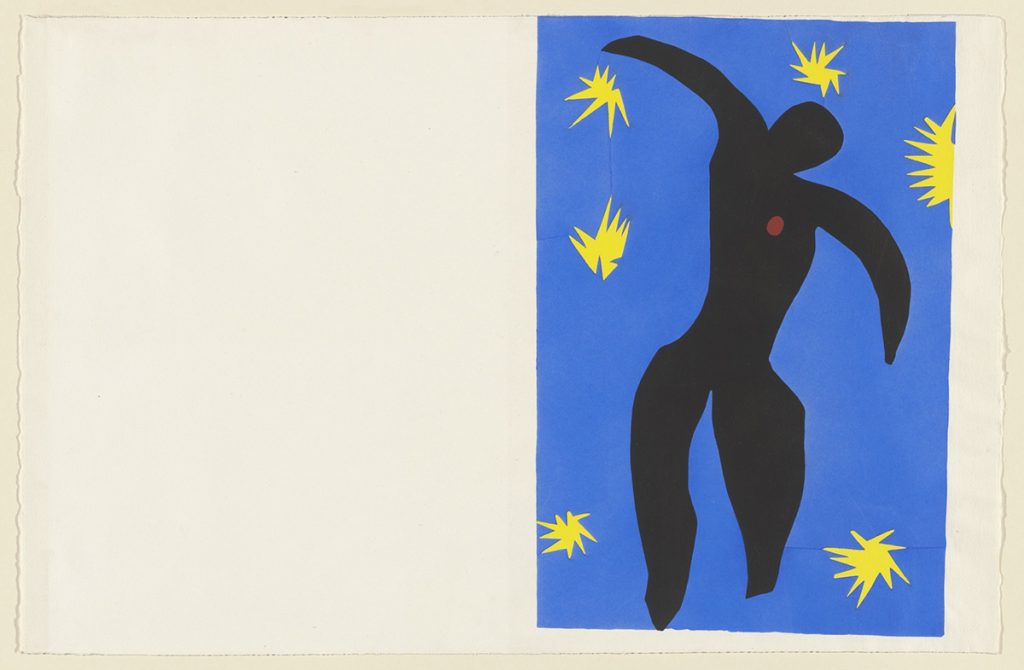

Conversely, many paintings have been created with particular pieces, or types, of music in mind. Artists such as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky were fascinated by the interrelation between music and painting. The idea that music is capable of evoking, through sound alone, images in the listener’s mind, became a big part of their artistic process: was it possible for a painting, if it somehow matched the tones, rhythms and moods of a particular piece of music, to have the same effect on the viewer as music might? This is something that many artists have strived to achieve, some with greater success than others.

Often an artist would choose a musical title for their painting because it perfectly fitted the narrative or the composition: Symphony in White, or Harmony in Grey and Green for example (both by Whistler, below and above). Some painters attempted to have no narrative at all and therefore used slightly more abstract titles such as Nocturne. Others took their titles directly from musical terminology, calling their paintings things like Andante or Allegro.

On a lighter note, some artists used Italian musical directions to cement their visual narratives. For example, Carel Weight’s Allegro Strepitoso below. Allegro means fast or lively, and strepitoso means noisy or boisterous. Indeed, I imagine that when lions escape their enclosures at the zoo it would be subito volante risoluto! Troppo scherzo? Attacca a tempo…

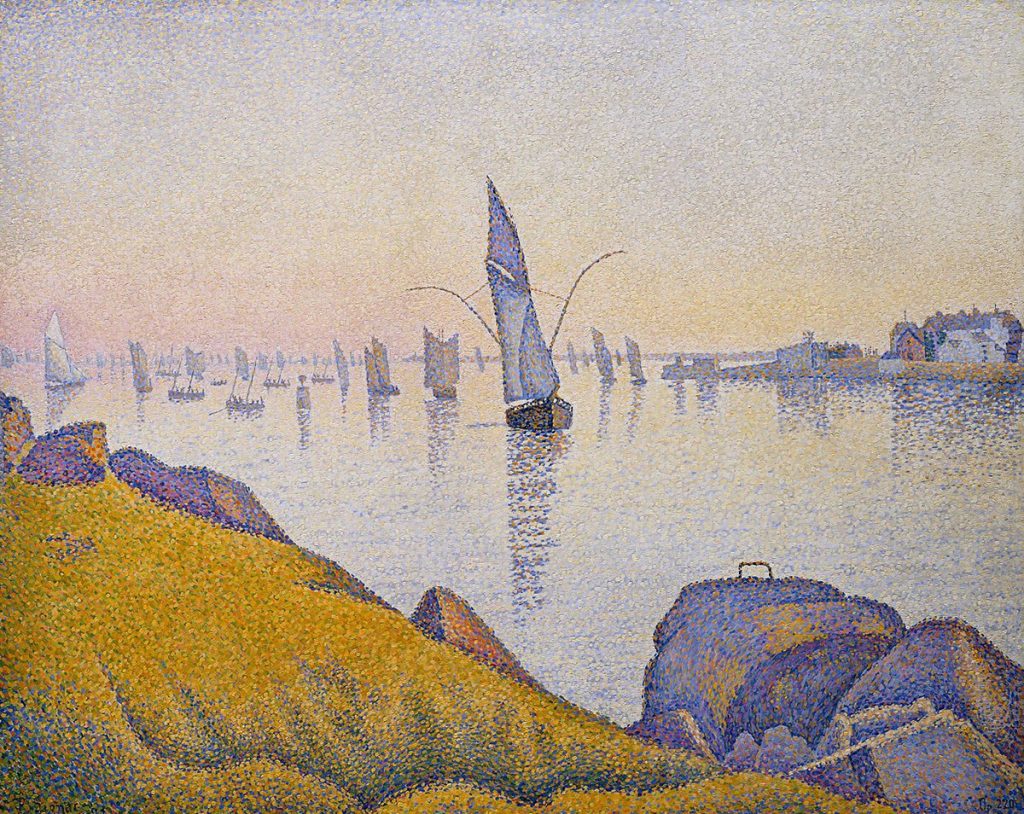

Music is a temporal art, its fullness becoming apparent over time. A painting can be absorbed in one moment. The idea of capturing a single mood has driven painters to break all the rules (the Impressionists were obsessed with this idea). As mentioned above, the mood that is created by music as it unfolds and imparts its secrets has long been a goal for painters to achieve too. Looking at the painting below: what can you hear?

Personally, I can be transported into all manner of imaginative, visual settings when listening to music: Claude Debussy’s Premiere Rhapsody (in particular performed by clarinetist Stanley Drucker) is one such piece into which I can be utterly drawn. However, a painting can’t do this for me: the experience of viewing alone remains separate unless I actively listen at the same time.

This is not true for everyone, and in fact, Kandinsky explored ideas relating to synesthesia, a condition in which senses that are normally separated become confused and overlap with one another. This essentially means that, for example, something seen with the eye can have a taste, or something heard with the ear can have a color. The process is involuntary, and the primary sense continues to function. So, someone might hear a chord in D Major, and as a secondary sensation taste gummy bears or see the color orange.

I do not have synesthesia, which is perhaps why when I look at art I do not hear sounds or taste things. But what must it be like to look at one of Whistler’s nocturnes and hear C Minor because the color blue is in that key? It is not surprising that, even watered down, this idea is incredibly engaging.

Leaving synesthesia behind, let’s go back for a moment to the idea of music as occupying temporal space, as opposed to art which occupies literally moments of observation. This could be seen as unfairly biased in favor of music (perhaps depending on the banal idea of how much time you want to spend listening or looking). Music, as we know, occurs over a period of time. To hear it all at once would make no sense (it would be a dissonant mess) unless you had musical talent to rival that of John Cage, in which case I’m sure it could be made to work.

A painting can be captured by the eye in a moment, even in passing if we’re being shamefully lazy. I do feel, however, that art could be seen as a way to bind the interpretation by the artist of the temporal, intangible nature of music into a solid object. Then, the object will remain spatially static for as long as it can be physically preserved, and a symbol of that artist’s musical experience perhaps.

The only problem I find with this is that if we haven’t heard the music to begin with, what should we tune in to when we are viewing the painting? Here the title of the art will be instrumental in invoking the right musical mood: perhaps when a painter creates a beautiful night scene while listening to a nocturne, and then also gives it that title, he hopes that we will hear a nocturne when we observe his work. This seems very logical, and yes, even I might hear Chopin’s Nocturne Op.9 No2 on viewing Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea. However, without such a pointer, I wouldn’t necessarily hear anything at all. It must be something peculiar to me that I don’t hear when I see, but I do see – copiously – when I hear! The quotation below clearly shows that not everyone is like me:

Our hearing of colors is so precise … Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.

Wassily Kandinsky, in: Concerning the Spiritual in Art, 1912.

What are your experiences? Have a think about it!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!