Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Nalini Malani (b. 1946) is a brilliant contemporary Indian artist. She is both prolific and internationally acclaimed.

“Over an extended career, Malani has been an unremitting voice for the silenced and the dispossessed, most particularly women globally. By alluding to a myriad of cultural references from both East and West, she has built an impressive body of work that engages viewers through complex, immersive installations that present her vision of the battered world we live in.”

Jury statement for the Joan Miró Prize, which Malani was awarded in May 2019.

Throughout the course of Malani’s glittering career (which has spanned five decades) her art is consistently feminist. Ironically, a senior male artist once told Malani that female art counts for nothing and that she’d better become a housewife.

Malani is a trailblazer for female Indian artists; her art challenges the role of women in patriarchal societies across the world.

“Understanding the world from a feminist perspective is an essential device for a more hopeful future, if we want to achieve something like human progress.”

“If humankind wants to survive the 21st century,” interview with curator Sophie Duplaix for “Malani retrospective” at Centre Pompidou, 2018.

While Malani shines a spotlight on patriarchy through art, her own achievements inspire and enable others. For example, she was the first woman to receive the prestigious Fukuoka Asian Art Prize (2013) and the first Indian to have a retrospective at the Centre Pompidou (and Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Torino 2018). Importantly, she organized the first-ever all-female art exhibition in India.

Between 1987 and 1989 “Through the Looking Glass” visited Bhopal, New Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore. Malani visited New York in 1979. There, the newly-opened A.I.R gallery inspired her. When she returned to India she spent years negotiating with public and private institutions in order to organize a similar space for Indian women.

The exhibition took place in public spaces in order to escape the elite atmosphere of art galleries. India has a specific context of a long and complicated history of caste and gender discrimination, nonetheless, the impact of Malani’s activism has created ripples the world over.

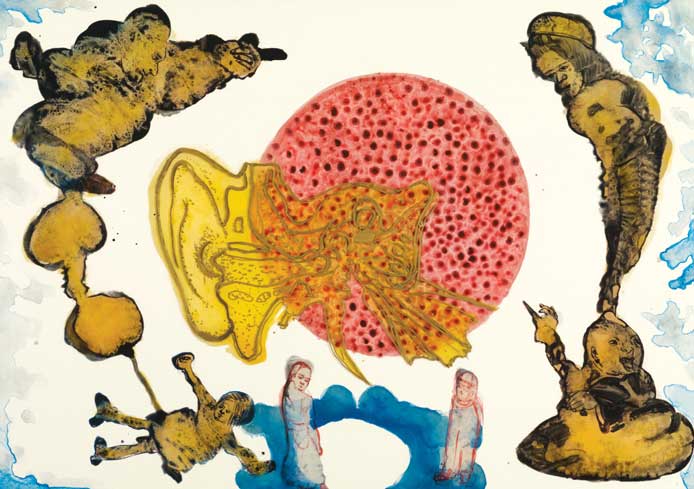

A figure that Malani often returns to is Cassandra – the Trojan princess from Greco-Roman mythology. Cassandra has the gift of prophecy but is cursed to be ignored. As a result, she suffers through the fall of Troy, witnesses her family being killed and is eventually raped, enslaved and murdered. In the bottom left of “Cassandra” (2009) is the tragic figure breathing out her prophecies. You can see visions of sickness, climate change and mass exodus; bodies and small writhing creatures feature. Christa Wolf’s novel, Cassandra (1983), tells the story of the Trojan War from Cassandra’s perspective – it was an inspiration for the 2009 exhibition where this piece was shown. Cassandra, for Malani, is a metaphor for ignored voices, especially those of women.

Much of Malani’s art draws on her experiences growing up as a refugee in the aftermath of the partition (1947), grappling with unfamiliar languages and cultures. When Malani was just one year old her family fled their home, traveling by boat and abandoning all their belongings, in order to seek refuge in Bombay.

I have no direct experience of Partition. It’s more the atmosphere that my mother and my grandparents lived with, the sense of loss – loss of culture and community, loss of language, loss of food

Interview published online on Art Radar, 21 March 2014.

From September 1997 to January 1988 the non-profit Eicher Gallery in New Delhi hosted “Mappings: shared histories.” This exhibition celebrated 50 years of independence and was created by Indian and Pakistani artists, including Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims. For this exhibition Malani created Excavated Images (now in a private collection) out of a quilt cover her grandmother had used to carry belongings during the partition.

The Indian Independence Act liberated the country from British rule. The partition was meant to solve social issues relating to resentments between religious groups. Unsurprisingly, dividing India and Pakistan according to a binary distinction of Secular and Muslim failed to account for the numerous ethnic groups, multifarious religious points of view and array of languages. The British did not plan the partition well. For example, it was brought forward by a year and the border was hastily decided in just five weeks. The sectarian violence that ensued, by some estimates, took more than two million human lives.

Remembering Toba Tek Singh (1998) was Malani’s first video play. It is a powerful protest against the Indian government’s nuclear tests. The video includes extracts from the famous short story of the same name, by Saadat Hasan Manto. The short story of the novel takes place a few years after independence and revolves around Bishan Singh, a Sikh inmate of an asylum in Lahore (the capital of the Pakistani province of Punjab) from the village Toba Tek Singh. Bishan Singh refuses to go to India when he hears that his hometown is in Pakistan. The video play opens with scenes of two young women, from either side of the Partition, failing to fold a sari, intermingled with images of the aftermath of the nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

When this video-play was originally shown, the director of the Prince of Wales Museum (Mumbai) wanted to shut down its exhibition. He was unsuccessful and over ten days the museum attracted more than 25,000 visitors.

Mother India: Transactions in the Construction of Pain (2005) shows archival footage of the Partition (1947) and the riots in Gujarat (2002). In both periods there was a sharp increase in the abduction and rape of women.

An essay by the sociologist Veena Das titled Language and Body: Transactions in the Construction of Pain informs this piece. This essay, like Malani’s video, explores how female bodies were a metaphor for the nation during the periods of unprecedented collective violence. Part of the film’s soundtrack is a blood-curdling scream.

As a child, Nalini Malan was able to travel abroad. This was a result of her father securing a job working for Air India. As an art student in the early 1970s, she spent two years in Paris, on a scholarship by the French government. She has completed residencies in India (1988), America (1989, 2005), Singapore (1999), Japan (1999/2000) and Italy (2003). Throughout her career, Malani has exhibited in over seventeen countries. As a result, there is no doubt that she is both an Indian artist and a global artist.

Her painters eye surpasses and embraces entire epochs and cultures, bridges contemporary events and mythology.

“You can’t keep acid in a paper bag 1969 – 2014,” Roobina Karode, published by Kirin Nadar Museum of Art, 2015.

The stories that she tells challenge the patriarchy, colonialism and religious fundamentalism (to name a few). Her art is powerful because Malani is a mesmerizing storyteller. Alongside literary references, Malani deploys ideas from popular culture and mythology. These synergies cut across cultures and histories.

Myths have been brought to us through the wisdom of civilisation, not by one single author. It’s almost as if the flotsam that comes in through the waves picks up things that are like jewels.

Art Radar, 21 March 2014.

Archetypal characters often feature in her work. Popular knowledge of figures from mythology allows her to continue mythological narratives and use them as a metaphor for contemporary issues.

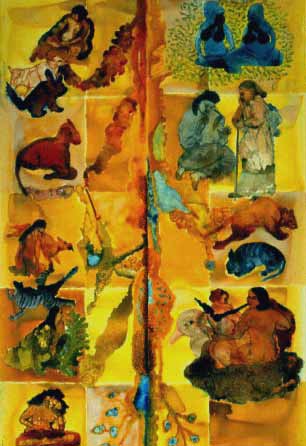

Medea and Sita are archetypes of betrayed women. Medea is an alchemist-witch-princess in Greek tragedy. She followed her husband into exile only for him to betray her. For revenge, she murders their two sons. Sita, the other protagonist in the Stories Retold series (an ongoing project of which this work is part of), is from the Hindu epic Ramayana. Like Medea, she is a princess who follows her husband into exile. Then, Ravana abducts Sita. After prolonged captivity, Sita’s husband rejects her because he thinks, wrongly, that she has committed adultery.

Malani’s Stories Retold project works with a worldwide range of legendary women: Greco-Roman figures like Medea and Cassandra, Bhagavata Purana, and Alice in Wonderland.

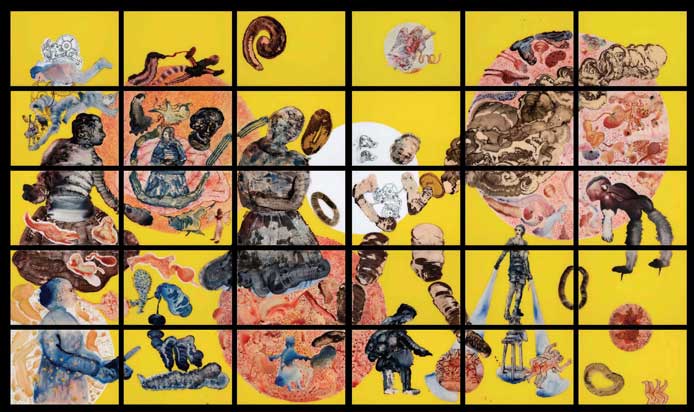

Despoiled Shore (1993) is an acrylic painting with charcoal on gypsum and hardboard. It was a backdrop for the Medeaprojekt (1991 – 1996) It combines depictions of anthropologists (left-side) with scenes from the Greek tragedy Medea (center). Scenes of the tragic Mumbai riots are on the final two panels. Betrayal and revenge metamorphose into a narrative about colonialism and religious fundamentalism.

The Medeaprojekt began as a collaboration with Alaknanda Samarth, actor and director. It was for a performance/installation piece that took place in 1993. The project, which works with Heiner Mueller’s adaptation of the Greek myth, spanned several years and generated many diverse works.

I often work with existing female characters from mythology, literature or history, to reintroduce male-dominated history from a female point of view.

Sophie Duplaix, Malani retrospective, Centre Pompidou, 2018.

By drawing cross-cultural links Malani’s mythologies coalesce into symbols that stretch beyond their original dimensions and are of direct relevance to contemporary events.

Malani’s layered narratives examine gender roles, race, transnational politics, and the ramifications of colonialism, globalization and consumerism. Her magnificent storytelling and beautiful art combine a wide array of mediums.

While a student Malani was part of a studio in Bombay which was shared by artists, musicians, actors and dancers. From this beginning, her career shows a journey of increasing collaboration as well as expansion beyond just a canvas.

Malani’s work began to more drastically incorporate mediums other than the canvas in protest against renewed religious conflicts in the 1990s. Malani even created a new form of art, the “video-play” (for which she coined the term), to allow her theatre plays to travel. Her video plays (Hamletmachine, 2000, Unity in Diversity, 2003, Mother India: Transactions in the Construction of Pain, 2005) are a huge success and have been shown in fourteen countries.

Hamletmachine (1999/2000) is Malani’s second Video-Play. It traveled to seventeen countries and was the poster and catalog image for her retrospective in 2018. Malani created the video installation during her residency at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum – where the video play will be shown in their upcoming anniversary exhibition. Hamletmachine works from the postmodernist retelling of Shakespeare’s Hamlet by the German playwright Heiner Müller (1929 – 1995).

The twenty-minute video is on four channels across three walls of square space. The floor of the space has a projection on a bed of salt, referencing Gandhi’s salt march (1930). Harada Nobuo, a Butoh (a type of Japanese dance theatre) performer from Fukuoka, is the protagonist in the video. The story is about a man who is born from salt and divided into four parts, which symbolize the Hindu caste hierarchy. He performs a prayer before becoming a cultural hybrid – wearing a Hindu dhoti and a Western business suit.

Clips from documentaries about Hindu fundamentalism intersperse the narrative. At the time independent filmmakers were beginning to draw attention to acute racism and caste hierarchy within the right-wing government through documentaries. The short video clips from these documentaries were given to Malani gratis by those wanting to give a voice to the voiceless.

Alongside her innovation of video-play, Malani also developed the form that she calls “video/shadow play.” This places her signature reverse painting onto rotating transparent cylinders. Then, light, video and sound are put into the mix.

The cylinders and the projections confront us with a whirlwind of such figures that flash memories of readings and photographs, paintings and drawings that feel like an archive of subaltern girls and women, including babies and umbilical cords. Young girls, caught in a history of violence and poverty, one with a leg blasted off by a mine, another, Alice-like, skipping rope as an innocent version of reiteration; a young homeless girl or protester peeing in public space, signifying poverty but also recalling the prestigious precedent of Rembrandt that we will see on the other side of the exhibition. Goya-like torture and execution; a monster morphing into a woman, or the opposite; the series goes on.

Mieke Bal, “Exposing Broken Promises: Nalini Malani’s multiple exposures,” , “Malani retrospective”, Centre Pompidou, 2018.

In 2010 San Francisco Art Institute awarded Malani an honorary doctorate, then she received the Fukuoka Asian Art Prize in 2013. The following year, she received the St Moritz Art Masters Lifetime Award and in 2015 the Asia Game Changer Award. She showed a video and shadow play on the western and southern facades of the Scottish National Gallery as part of the commemoration of the centenary of the UK’s entry into WW1 (2014). Between 2017 and 2018 her retrospective was at the Centre Pompidou and Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Torino. In early 2019 Malani won the Joan Miró Prize.

Today, Nalini Malani continues to live and work in Bombay.

Please visit her website to read excellent essays and further explore her work. You can watch clips of her artwork on her Youtube channel.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!